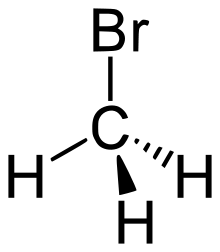

Bromomethane

| Bromomethane | |

|---|---|

| |

|

|

| IUPAC name Bromomethane[1] | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 74-83-9 |

| PubChem | 6323 |

| ChemSpider | 6083 |

| EC number | 200-813-2 |

| KEGG | C18447 |

| MeSH | methyl+bromide |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:39275 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL48339 |

| RTECS number | PA4900000 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1209223 |

| Gmelin Reference | 916 |

| Jmol-3D images | Image 1 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | CH3Br |

| Molar mass | 94.94 g mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless gas |

| Odor | Chloroform |

| Density | 3.974 mg mL−1 (at 20 °C) |

| Melting point | −93.66 °C; −136.59 °F; 179.49 K |

| Boiling point | 3.5 °C; 38.2 °F; 276.6 K |

| Solubility in water | 15.22 g L−1 |

| log P | 1.3 |

| Vapor pressure | 190 kPa (at 20 °C) |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std enthalpy of formation ΔfH |

−35.1–−33.5 kJ mol−1 |

| Hazards | |

| EU Index | 602-002-00-2 |

| EU classification | |

| R-phrases | R23/25, R36/37/38, R48/20, R50, R59, R68 |

| S-phrases | (S1/2), S15, S27, S36/39, S38, S45, S59, S61 |

| NFPA 704 |

1

3

0

|

| Flash point | <−30 °C; −22 °F; 243 K |

| Autoignition temperature | 535 °C; 995 °F; 808 K |

| Explosive limits | 8.6–20% |

| Related compounds | |

| Related alkanes | |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |

| Infobox references | |

Bromomethane, commonly known as methyl bromide, is an organobromine compound with formula CH3Br. This colorless, odorless, nonflammable gas is produced both industrially and particularly biologically. It has a tetrahedral shape and it is a recognized ozone-depleting chemical. It was used extensively as a pesticide until being phased out by most countries in the early 2000s.

Occurrence and manufacture

Bromomethane originates from both natural and human sources. In the ocean, marine organisms are estimated to produce 1-2 billion kilograms annually.[2] It is also produced in small quantities by certain terrestrial plants, such as members of the Brassicaceae family. It is manufactured for agricultural and industrial use by reacting methanol with hydrogen bromide:

- CH3OH + HBr → CH3Br + H2O

Uses

In 1999, an estimated 71,500 tonnes of synthetic methyl bromide were used annually worldwide.[3] 97% of this estimate is used for fumigation purposes, whilst 3% is used for the manufacture of other products. Moreover 75% of the consumption takes place in developed nations, led by the U.S (43%) and Europe (24%). Asia and the Middle East combine to use 24% whereas Latin America and Africa have the lowest consumption rates at 9%.[3]

Until its production and use was curtailed by the Montreal Protocol, bromomethane was widely applied as a soil sterilant, mainly for production of seed but also for some crops such as strawberries and almonds. In commercial large-scale monoculture seed production, unlike crop production, it is of vital importance to avoid contaminating the crop with off-type seed of the same species. Therefore, selective herbicides cannot be used. Whereas bromomethane is dangerous, it is considerably safer and more effective than some other soil sterilants. Its loss to the seed industry has resulted in changes to cultural practices, with increased reliance on soil steam sterilization, mechanical rogueing, and fallow seasons. Bromomethane was also used as a general-purpose fumigant to kill a variety of pests including rats and insects. Bromomethane has poor fungicidal properties. Bromomethane is the only fumigant allowed (heat treatment is only other option) under ISPM 15 regulations when exporting solid wood packaging (forklift pallets, crates, bracing) to ISPM 15 compliant countries. Bromomethane is used to prepare golf courses, particularly to control Bermuda grass. The Montreal Protocol stipulates that bromomethane use be phased out.

Bromomethane is also a precursor in the manufacture of other chemicals as a methylating agent, and has been used as a solvent to extract oil from seeds and wool.

Bromomethane was once used in specialty fire extinguishers, prior to the advent of less toxic halons, as it is electrically non-conductive and leaves no residue. It was used primarily for electrical substations, military aircraft, and other industrial hazards. It was never as popular as other agents due to its high cost and toxicity. Bromomethane was used from the 1920s to the 60s, and continued to be used in aircraft engine fire suppression systems into the late 60s.

Regulation

Bromomethane is readily photolyzed in the atmosphere to release elemental bromine, which is far more destructive to stratospheric ozone than chlorine. As such, it is subject to phase-out requirements of the 1987 Montreal Protocol on Ozone Depleting Substances.

The London Amendment in 1990 added methyl bromide to the list of ODS to be phased out. In 2003 the Global Environment Facility approved funds for a UNEP-UNDP joint project for methyl bromide total sector phase out in seven countries in Central Europe and Central Asia, due for completion in 2007.[4]

Alternatives

Many alternatives for Bromomethane in the agricultural field are currently in use and yet further alternatives are in development, not least of which include Propylene oxide and Furfural.[5]

Australia

In Australia, bromomethane (methyl bromide) is the preferred fumigant required by the Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service (AQIS) for most organic goods imported into Australia.[6] AQIS conducts methyl bromide fumigation certification for both domestic and foreign fumigators who can then fumigate containers destined for Australia. A list of alternative fumigants is available for goods imported from Europe (known as the ICON database), where methyl bromide fumigation has been banned.[7] Alternatively, AQIS allows containers from Europe to be fumigated with methyl bromide on arrival to Australia.

New Zealand

In New Zealand, bromomethane is used as a fumigant for whole logs destined for export. Environmental groups and the Green Party oppose its use.[8][9] In May 2011 the Environmental Risk Management Authority (ERMA) introduced new rules for its use which restrict the level of public exposure to the fumigant, set minimum buffer zones around fumigation sites, provide for notification to nearby residents and require users to monitor air quality during fumigations and report back to ERMA each year. All methyl bromide fumigations must use recapture technology by 2021.[10]

United States

In the United States bromomethane is regulated as a pesticide under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA; 7 U.S.C. 136 et seq.) and as a hazardous substance under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA; 42 U.S.C. 6901 et seq.), and is subject to reporting requirements under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA; 42 U.S.C. 11001 et seq.). The U.S. Clean Air Act (CAA; 42 U.S.C. 7401 et seq.). A 1998 amendment (P.L. 105-178, Title VI) conformed the Clean Air Act phase out date with that of the Montreal Protocol.[11][12] Whereas the Montreal Protocol has severely restricted the use of bromomethane internationally, the United States has successfully lobbied for critical-use exemptions. In 2004, over 7 million pounds of bromomethane were applied to California. Applications include tomato, strawberry, and ornamental shrub growers, and fumigation of ham/pork products. Also exempt is the treatment of solid wood packaging (forklift pallets, crates, bracing), and the packaged goods, being exported to ISPM 15 countries(to include Canada in 2012).

Chile

Has to phase out the use in agriculture by 2015.[13]

Health effects

Brief exposure to high concentrations and prolonged inhalation of lower concentrations are problematic.[14] Exposure levels leading to death vary from 1,600 to 60,000 ppm, depending on the duration of exposure (as a comparison exposure levels of 70 to 400 ppm of carbon monoxide cover the same spectrum of illness/death).

"A TLV–TWA of 1 ppm (3.89 mg/m3) is recommended for occupational exposure to methyl bromide"-ACGIH 8 hour time weighted average. Immediately Dangerous To Life or Health Concentration by NIOSH: "The revised IDLH for methyl bromide is 250 ppm based on acute inhalation toxicity data in humans [Clarke et al. 1945]. This may be a conservative value due to the lack of relevant acute toxicity data for workers exposed to concentrations above 220 ppm. [Note: NIOSH recommends as part of its carcinogen policy that the "most protective" respirators be worn for methyl bromide at any detectable concentration.]" Detectable concentration by Drager Tube is 0.5 ppm.

Respiratory, kidney, and neurological effects are of the greatest concern. Scientists have investigated whether bromomethane exposure was linked to the death of four New Zealand port workers who died of neuro-degenerative motor neurone disease between 2002 and 2004 and found no connection.

"Cases of severe methyl bromide poisoning in humans, some of them fatal, were frequently reported. For example, von Oettingen recorded 47 fatal and 174 nonfatal cases of methyl bromide intoxication between 1899 and 1952...Severe poisoning with some fatalities resulted from soil disinfection by injection of methyl bromide into greenhouse soil."-ACGIH

Treatment of wood packaging requires a concentration of up to 16,000 ppm. An Australian Customs officer died of methyl bromide poisioning while inspecting a shipping container that was fumigated in the United States[citation needed]. Canada Border Services Officers avoided the same fate[citation needed] because a Mexican container of granite was fumigated with 98% methyl bromide and 2% chloropicrin fumigant, the chloropicrin has a tear-gas effect.

NIOSH considers methyl bromide to be a potential occupational carcinogen as defined by the OSHA carcinogen policy [29 CFR 1990]. "methyl bromide showed a significant dose-response relationship with prostate cancer risk" -www.aghealth.org

Excessive exposure

Expression of toxicity following exposure may involve a latent period of several hours, followed by signs such as nausea, abdominal pain, weakness, confusion, pulmonary edema, and seizures. Individuals who survive the acute phase often require a prolonged convalescence. Persistent neurological deficits such as asthenia, cognitive impairment, optical atrophy, and paresthesia are frequently present after moderate to severe poisoning. Blood or urine concentrations of inorganic bromide, a bromomethane metabolite, are useful to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to assist in the forensic investigation of a case of fatal overdosage.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ "methyl bromide - Compound Summary". PubChem Compound. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information. 26 March 2005. Identification. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ↑ Gribble, G. W. (1999). "The diversity of naturally occurring organobromine compounds". Chemical Society Reviews 28 (5): 335–346. doi:10.1039/a900201d.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Towards Methyl Bromide Phase Out: A Handbook for National Ozone Units". UNEP. 1 August 1999.

- ↑ "Information on Commercially Validated Methyl Bromide Alternative Technologies". UNEP. 14 September 2009.

- ↑ http://www.epa.gov/ozone/mbr/alts.html

- ↑ "Methyl Bromide - Questions and Answers". Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ↑ "Methyl Bromide - Questions and Answers". Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ↑ "Methyl Bromide Threat Again in Picton". Guardians of the Sounds. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ↑ Kedgley, Sue (2008-02-02). "Picton residents need protection from poison fumes: Greens". Green Party. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ↑ "New rules for methyl bromide fumigations". Environmental Risk Management Authority. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ "The Phaseout of Methyl Bromide". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑ CRS Report for Congress: Agriculture: A Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition - Order Code 97-905

- ↑ Decision XVII/29: Non-compliance with the Montreal Protocol by Chile. United Nations Environment Programme Ozone Secretariat, http://montreal-protocol.org/publications/mp_handbook/Section_2_Decisions/Article_8/decs-non-compliance/Decision_XVII-29.shtml

- ↑ Muir, GD (ed.) 1971, Hazards in the Chemical Laboratory, The Royal Institute of Chemistry, London.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 982-984.

External links

- Chemical Alternatives to the agricultural use of Methyl Bromide

- Biological, Chemical & Practice based alternatives to the agricultural use of Methyl Bromide.

- Methyl Bromide Technical Fact Sheet - National Pesticide Information Center

- Methyl Bromide General Fact Sheet - National Pesticide Information Center

- Methyl Bromide Pesticide Information Profile - Extension Toxicology Network

- International Chemical Safety Card 0109

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards 0400

- Institut national de recherche et de sécurité (1992). "Bromométhane." Fiche toxicologique n° 67. Paris:INRS. (French)

- IARC Summaries & Evaluations Vol. 71 (1999)

- The banned pesticide in our soil

- MSDS at Oxford University

- Toxicological profile

- Environmental Health Criteria 166

- OECD SIDS document

- EPA 2010 Critical Use Exemption Nominations

- ChemSub Online (Methyl bromide, Bromomethane).

| |||||||||||||||||