Bromoil Process

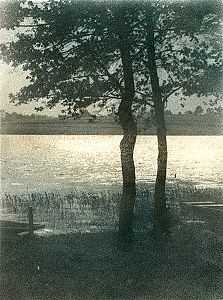

The Bromoil Process was an early photographic process that was very popular with the Pictorialists during the first half of the twentieth century. The soft, paint-like qualities of the prints are very typical for this genre, and have recently led to some art photographers using the process again.

The bromoil process was based on the oil print, whose origins go back to the mid-nineteenth century. A drawback of oil prints was that the gelatin used was too slow to permit an enlarger to be used, so that negatives had to be the same dimensions as the positives. After G.E.H. Rawlins published a 1904 article on the oil print process, E.J. Wall in 1907 described theoretically how it should be possible to use a smaller negative in an enlarger to produce a silver bromide positive, which should then be bleached and hardened, to be inked afterwards as in the oil process. C Welborne Piper then executed this theory in practice, and so the bromoil process was born.

Method

To explain the bromoil process, it is helpful to look at the oil print first. The prints are made on paper with a thick gelatin layer that has been sensitized with dichromate salts. Exposure using a negative for contact-print leads to hardening of the dichromated gelatin, in direct relation of the amount of light received. After exposure, the print gets soaked in water. The non-hardened parts absorb more water than the hardened parts, so after sponge-drying the print, while still moist, one can apply a lithographic ink to the oil-base. The non-mixing character of oil and water results in a coloring of the exposed parts of the print, creating a positive image. The ink application requires considerable skill, and as a result no two prints are alike.

Bromoil prints are a direct variety of this process: One starts with a normally developed print on a silver bromide paper which is then chemically bleached and hardened. The gelatin which originally had the darkest tones, is hardened the most, the highlights remain absorbent to water. This print can then be inked like the oil print.

Long-term effects on stability:

Inadequate rinsing of the chrome salts can lead to discoloration of the prints under influence of light in the longer term. The irregular thickness of the gelatin layer can, in unfavourable conditions, lead to stresses in the pictorial layer, which can be damaged this way.

This technique was used to produce color prints into the 1930s before the color-film was developed: Three identical black & white photographic takes of an object were made on Ilford Hypersensitive Panchromatic film with the corresponding filters (blue, green, red) The developed negatives were enlarged and transposed on bromide-silver photographic paper. The bromide-silver layer was bleached and tanned as described above. Rather hard bromoil ink was applied, yellow on the blue-filtered, red on the green-filtered and blue on the red-filtered matrice. The fine-graded colored matrices, exactly fitted one above the other, are passed alternately through an etching press. Thus a transferred color picture on absorbing and fibre-free paper or even cloth is produced (cf. links below F. Rontag). A picture appears that reminds the beholder of pastel-paintings, which however show the distinctivenes of detail and contour of photography.

References

- AlternativePhotography - Make bromoil prints

- AlternativePhotography - Make bromoil Oil prints

- International Society of Bromoilists

- Nikolai Andreev - master of pictorial photography

- Franz Rontag, 3-colour bromoil transfer 1930s

| Alternative photography |

|---|

|