British space programme

The British space programme is the UK government's work to develop British space capabilities. The objectives of the current civil programme are to "win sustainable economic growth, secure new scientific knowledge and provide benefits to all citizens."[1]

The British space programme has always emphasized unmanned space research and commercial initiatives. It has never been government policy to create a British astronaut corps.[2][3] The British government does not provide funding for the International Space Station.[4]

The first official British space programme began in 1959 with the Ariel series of British satellites, built in the USA and the UK and launched using American rockets. The first British satellite, Ariel 1, was launched in 1962.

During the 1960s and 1970s, a number of efforts were made to develop a British satellite launch capability. A British rocket named Black Arrow did succeed in placing a single British satellite, Prospero, into orbit from a launch site in Australia in 1971. Prospero remains the only British satellite to be put into orbit using a British vehicle.

The British National Space Centre was established in 1985 to co-ordinate British government agencies and other interested bodies in the promotion of British participation in the international market for satellite launches, satellite construction and other space endeavours.

In 2011, many of the various separate sources of space-related funding were combined and allocated to the Centre's replacement, the UK Space Agency. Among other projects, the agency is funding a single-stage-to-orbit spaceplane concept called Skylon.

Origin of the space programme

Scientific interest in space travel existed in the United Kingdom prior to World War II, particularly amongst members of the British Interplanetary Society (founded in 1933) whose members included Sir Arthur C. Clarke, author and conceiver of the geostationary telecommunications satellite, who joined the BIS after World War II.

As with the other post-war space-faring nations, the British government's initial interest in space was primarily military. Early programmes reflected this interest. As with other nations, much of the rocketry knowledge was obtained from captured German scientists who were persuaded to work for the British. The British performed the earliest post-war tests of captured V-2 rockets in Operation Backfire, less than six months after the end of the war in Europe.

Initial work was done on smaller air to surface missiles such as Blue Steel before progress was made towards launches of larger orbit-capable rockets.

British satellite programmes (1959–present)

Early satellite programmes

The Ariel programme developed six satellites between 1962 and 1979, all of which were launched by NASA.

In 1971, the last Black Arrow (R3) launched Prospero X-3, the only British satellite to be launched using a British rocket. Ground contact with Prospero ended in 1996.

Military satellite programmes

Skynet is a purely military programme, operating a set of satellites on behalf of the UK Ministry of Defence.

Skynet provides strategic communication services to the three branches of the British Armed Forces and to NATO forces engaged on coalition tasks. The first satellite was launched in 1969, and the most recent in 2012.

Skynet is the most expensive single UK space project, although as a military initiative it is not part of the civil space programme.

Intelligence satellite programmes

Zircon was the codename for a British signals intelligence satellite, intended to be launched in 1988, before being cancelled. During the Cold War, Britain's Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) was very reliant on America's National Security Agency (NSA) for communications interception from space. GCHQ therefore decided to produce a UK-designed-and-built signals intelligence satellite, to be named Zircon, a code-name derived from zirconium silicate, a diamond substitute.

Zircon's function was to intercept radio and other signals from the USSR, Europe and other areas. The satellite was to be built by Marconi Space and Defence Systems at Portsmouth Airport, in which a new high security building had been built.

It was to be launched on a NASA Space Shuttle under the guise of Skynet IV. Launch on the Shuttle would have entitled a British National to fly as a Mission Specialist and a group of military pilots were presented to the press as candidates for 'Britain's first man in space'.

Zircon was cancelled by Chancellor Nigel Lawson on grounds of its cost in 1987. The subsequent scandal about the true nature of the project became known as the Zircon Affair.

British space vehicles (1950–1985)

Britain developed and launched several space rockets, as well as developing space planes. During this period, the launcher programmes were administered in succession by the Ministry of Supply, the Ministry of Aviation, the Ministry of Technology and the Department of Trade and Industry.

Development of a British launch system to carry a nuclear device occurred from 1950 onwards.

Rockets were tested on the Isle of Wight and RAF Spadeadam, Cumbria and both tested and launched from Woomera in South Australia. These included the Black Knight and Blue Streak rockets.

A major satellite launch vehicle was proposed in 1957 based on Blue Streak and Black Knight technology. This was named Black Prince, but the project was cancelled in 1960 due to lack of funding. Blue Streak rockets continued to be launched as the first stage of the European Europa carrier rocket until Europa's cancellation in 1972.

The smaller Black Arrow launcher was developed from Black Knight and was first launched in 1969 from Woomera. In 1971, the last Black Arrow (R3) launched Prospero X-3, the only British satellite to be launched using a British rocket.

By 1972, UK government funding of both Blue Streak (missile) and Black Arrow had ceased, and no further government-backed British space rockets were developed. Other space agencies, notably NASA, were used for subsequent launches of UK satellites. Communication with the Prospero X-3 was terminated in 1996.

Falstaff, a British hypersonic test rocket, was launched from Woomera between 1969 and 1979.

The official national space programme was revived in 1982 when the British government funded the HOTOL project, an ambitious attempt at a re-usable space plane using air-breathing rocket engines designed by Alan Bond. Work was begun by British Aerospace. However, having classified the engine design as 'top secret' the government then ended funding for the project, terminating it.

National space programme (1985–2010)

In 1985 the British National Space Centre (BNSC) was formed to coordinate UK space activities.[5]

The BNSC was the third largest financial contributor to the General Budget of the European Space Agency, contributing 17.4%,[6] to its Science Programme and to its robotic exploration initiative the Aurora programme.

The UK decided not to contribute funds for the International Space Station, on the basis that it did not represent value for money.[7] The British government did not take part in any manned space endeavours during this period.

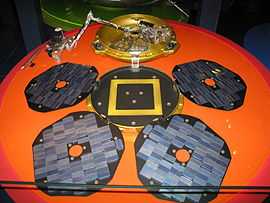

Britain continued to contribute scientific elements to satellite launches and space projects. The British probe Beagle 2, sent as part of the ESA's Mars Express to study the planet Mars, was lost when it failed to respond.

United Kingdom Space Agency (2010 – present)

On 1 April 2010, the government established the UK Space Agency, an agency responsible for the British space programme. It replaced the British National Space Centre and now has responsibility for government policy and key budgets for space, as well as representing the UK in all negotiations on space matters.

The UK Space Agency provides 6% of the European Space Agency budget.

Reaction Engines Skylon

The British government partnered with the ESA in 2010 to promote a single-stage to orbit spaceplane concept called Skylon.[8] This design was pioneered by Reaction Engines Limited,[9][10] a company founded by Alan Bond after HOTOL was cancelled.[11] The Skylon spaceplane has been positively received by the British government, and the British Interplanetary Society.[12] Pending a successful engine test in June 2011,[13] the company will begin Phase 3 of development with the first orders expected around 2011-2013.

2011 budget boost and reforms

The UK government is proposing reform to the 1986 Outer Space Act in several areas, including the liabilities that cover space operations, in order to enable British companies space endeavors to better compete with international competitors. There is also a proposal of a £10 million boost in capital investment that is to be matched by industry.[14]

Commercial and private space activities

The first Briton in space, cosmonaut-researcher Helen Sharman, was funded by a private consortium without UK government assistance. Interest in space continues in Britain's private sector, including satellite design and manufacture, developing designs for space planes and catering to the new market in space tourism.

Project Juno

Project Juno was a private space programme, which selected Helen Sharman to be the first Briton in space. A private consortium was formed to raise money to pay the USSR for a seat on a Soyuz mission to the Mir space station. The USSR had recently flown Toyohiro Akiyama, a Japanese journalist, by a similar arrangement.

A call for applicants was publicized in the UK and Sharman was chosen for the flight with Major Timothy Mace as her backup. The cost of the flight was to be funded by various innovative schemes, including sponsoring by private British companies and a lottery system. Corporate sponsors included British Aerospace, Memorex, and Interflora, and television rights were sold to ITV.

Ultimately the Juno consortium failed to raise the entire sum, and the USSR considered canceling the mission. It is believed that Mikhail Gorbachev directed the mission to proceed at Soviet cost.

Sharman was launched aboard Soyuz TM-12 on 18 May 1991, and returned aboard Soyuz TM-11 on 26 May 1991.

Surrey Satellite Technology

Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd (SSTL) is a large spin-off company of the University of Surrey, now fully owned by EADS Astrium, that builds and operates small satellites. SSTL works with the UK Space Agency and takes on a number of tasks for the UKSA that would be done in-house by a traditional large government space agency.

Virgin Galactic

Virgin Galactic, a US company within the British-based Virgin Group owned by Sir Richard Branson, is taking reservations for suborbital space flights from the general public. Its operations will use SpaceShipTwo space planes designed by Scaled Composites, which has previously developed the Ansari X-Prize winning SpaceShipOne.

British contribution to other space programmes

Communication and tracking of rockets and satellites in orbit is achieved using stations such as Jodrell Bank. During the Space Race, Jodrell Bank and other stations were used to communicate with several satellites and probes including Sputnik and Pioneer 5.[citation needed]

As well as providing tracking facilities for other nations, scientists from the United Kingdom have participated in other nation's space programmes,[citation needed] notably contributing to the development of NASA's early space programs,[15] and co-operation with Australian launches.[citation needed]

British astronauts

Because the UK government has never developed a manned spaceflight programme and does not contribute any funding to the manned space flight part of ESA's activities, the few British-born astronauts have launched with either the American or Soviet/Russian space programmes. Despite this, on October 9, 2008, UK Science and Innovation Minister Lord Drayson spoke favourably of the idea of a British astronaut.[16]

To date, six British-born astronauts and one non-British born UK citizen have flown in space:

| Name | Birthplace | Missions | First launch date | Nationality/ies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helen Sharman | Grenoside, Sheffield, South Yorkshire | Soyuz TM-12/11 | 18 May 1991 | |

| First Briton in space. Funded partially by private UK citizens as Project Juno and by the Soviet Union. | ||||

| Michael Foale | Louth, Lincolnshire | STS-45 (Atlantis) STS-56 (Discovery) STS-63 (Discovery) STS-84/86 (Atlantis) STS-103 (Discovery) Soyuz TMA-3 |

24 March 1992 | |

| Stayed on both Mir and the International Space Station as a NASA astronaut. On 9 February 1995, during STS-63, he became the first Briton to perform an extra-vehicular activity. He is a US citizen through his mother. | ||||

| Mark Shuttleworth | Welkom, Orange Free State, South Africa | Soyuz TM-34/33 | 27 April 2002 | |

| Self-funded "space tourist" to the International Space Station. Born a South African, he also holds UK citizenship. | ||||

| Piers Sellers | Crowborough, Sussex | STS-112 (Atlantis) STS-121 (Discovery) STS-132 (Atlantis) |

7 October 2002 | |

| NASA astronaut. US citizen since 1991. | ||||

| Nicholas Patrick | Saltburn-by-the-Sea, North Yorkshire | STS-116 (Discovery) STS-130 (Endeavour) |

9 December 2006 | |

| NASA astronaut. US citizen since 1994. | ||||

| Gregory H. Johnson | South Ruislip, Middlesex | STS-123 (Endeavour) STS-134 (Endeavour) |

11 March 2008 | |

| NASA astronaut. Born in UK to US parents. | ||||

| Richard Garriott | Cambridge, Cambridgeshire | Soyuz TMA-13/12 | 12 October 2008 | |

| Self-funded "space tourist" to the International Space Station. Born in UK to US parents (son of Skylab astronaut Owen Garriott). | ||||

Dr. Anthony Llewellyn (born in Cardiff, Wales) was selected as a scientist-astronaut by NASA during August 1967 but resigned during September 1968, having never flown in space.

Army Lieutenants-Colonel Anthony Boyle (born in Kidderminster) and Richard Farrimond (born in Birkenhead, Cheshire), MoD employee Christopher Holmes (born in London), Royal Navy Commander Peter Longhurst (born in Staines, Middlesex) and RAF Squadron Leader Nigel Wood (born in York) were selected in February 1984 as payload specialists for the Skynet 4 Program, intended for launch using the Space Shuttle. Boyle resigned from the program in July 1984 due to Army commitments. Prior to the cancellation of the missions after the Challenger disaster, Wood was due to fly aboard Shuttle mission STS-61-H in 1986 (with Farrimond serving as his back-up) and Longhurst was due to fly aboard Shuttle mission STS-71-D in 1987 (with Holmes serving as back-up). All resigned in 1986, having not flown.

Army Air Corps Major Timothy Mace (born in Catterick, Yorkshire) served as back-up to Helen Sharman for the Soyuz TM-12 / Project Juno mission in 1991. He resigned in 1991, having not flown.

On May 20, 2009, the European Space Agency (ESA) announced that Major Timothy Peake, an Army Air Corps test pilot from Chichester, West Sussex, had been accepted as a member of the European Astronaut Corps.[17] In May, 2013, the ESA announced that Peake would fly to the International Space Station (ISS) aboard a Soyuz rocket from Baikonur in Kazakhstan but not before 2015.[18]

In fiction

Works of science fiction have often described a United Kingdom with an ambitious space programme of its own. Notable fictional depictions of British spacecraft or Britons in space include:

- "How We Went to Mars" by Sir Arthur C. Clarke (Amateur Science Fiction Stories March 1938).

- Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future (comics, 1950–1967, 1980s).

- Journey Into Space (radio, 1953–1955).

- The Quatermass Experiment (television, 1953).

- Blast Off at Woomera by Hugh Walters (1957).

- Doctor Who (television) — "The Ambassadors of Death" (1970), "The Christmas Invasion" (2005), "The Waters of Mars" (2009).

- The Goodies - "Invasion of the Moon Creatures"(television, 1973).

- Moonbase 3 (television, 1973).

- Come Back Mrs. Noah (television, 1977).

- Moonraker (film) (1979).

- Star Cops (television, 1987).

- Red Dwarf (television, 1988–1999, 2009).

- Ministry of Space (comics, 2001–2004).

- Space Cadets (TV series) (television, 2005).

- Hyperdrive (TV series) (television, 2006–2007).

See also

- British National Space Centre replaced by the UK Space Agency in 2010

- National Space Centre (Leicester)

- British Rail flying saucer

References

- ↑ "What we do". BIS. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- ↑ "UK vision to stay at the forefront of space sector published". Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ Sample, Ian (14 February 2008). "UK carves out its place in space, but hopes for Britons on moon dashed". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ Lunan, Duncan (Nov 2001). "Promoting UK involvement in the ISS: a space station lifeboat?". Space Policy 17 (4): 249–255. doi:10.1016/S0265-9646(01)00039-X.

- ↑ "BNSC:How we work". Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "BNSC and ESA". Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ↑ "Space station 'not worth' joining". BBC News. BBC. 1999-02-18. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ↑

- ↑ Reaction Engines Limited FAQ

- ↑

- ↑ Reaction Engines Ltd 2006

- ↑ Robert Parkinson (2011-02-22). "SSTO spaceplane is coming to Great Britain". Space:The Development of Single Stage Flight. The Global Herald. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ↑ Background "Skylon Test Date". UK Parliament. 21 January 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (2011-03-23). "UK space given boost from Budget". BBC. Retrieved 2011-03-24. "reforms are designed to lower the sector's insurance costs and to make it easier for future space tourism companies to operate out of the UK. The government says it has recognised the success the British space sector has achieved in recent years and wants to offer it further support to maintain and grow its global market position."

- ↑ Eugene Kranz, Failure is not an Option

- ↑ Minister wants astronaut 'icon'

- ↑ "Europe unveils British astronaut". BBC News. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ↑ "UK astronaut Tim Peake to go to International Space Station". BBC News. 19 May 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

External links

- British National Space Centre

- History of British rocketry

- Britain in Space

- Information on Blue Streak

- History of HOTOL

- Virgin Galactic

- UK made 'fundamental space mistake'

- BBC Report on SST

- BBC, March 24, 2011, article on recent UK government announcement contrasted with recent French government funding increases.

- Other resources

- Hill, C.N., A Vertical Empire: The History of the UK Rocket and Space Programme, 1950-1971

- Millard, Douglas, An Overview of United Kingdom Space Activity 1957-1987, ESA Publications.