Cape Colony

| Cape Colony Kaapkolonie | |||||

| British colony | |||||

| |||||

|

| |||||

| Anthem God Save the King (God Save the Queen 1837–1901) | |||||

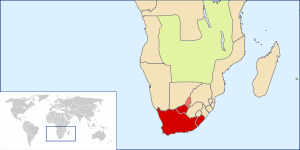

The Cape Colony ca. 1890 with Griqualand East and Griqualand West annexed and Stellaland/Goshen (in light red) claimed | |||||

| Capital | Cape Town | ||||

| Languages | English, Dutch ¹ | ||||

| Religion | Dutch Reformed Church, Anglican | ||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||

| King/Queen | |||||

| - | 1795–1820 | George III | |||

| - | 1820–1830 | George IV | |||

| - | 1830–1837 | William IV | |||

| - | 1837–1901 | Queen Victoria | |||

| - | 1901–1910 | Edward VII | |||

| Governor | |||||

| - | 1797–1798 | George Macartney | |||

| - | 1901–1910 | Walter Hely-Hutchinson | |||

| Prime Minister | |||||

| - | 1872–1878 | John Charles Molteno | |||

| - | 1908–1910 | John X. Merriman | |||

| Historical era | Scramble for Africa | ||||

| - | Established | 1795 | |||

| - | Dutch colony | 1803–1806 | |||

| - | Anglo-Dutch treaty | 1814 | |||

| - | Natal incorporated | 1844 | |||

| - | Disestablished | 1910 | |||

| Area | |||||

| - | 1822[1] | 331,900 km² (128,147 sq mi) | |||

| - | 1910 | 569,020 km² (219,700 sq mi) | |||

| Population | |||||

| - | 1822[1] est. | 110,380 | |||

| Density | 0.3 /km² (0.9 /sq mi) | ||||

| - | 1865 census[2] est. | 496,381 | |||

| - | 1910 est. | 2,564,965 | |||

| Density | 4.5 /km² (11.7 /sq mi) | ||||

| Currency | Pound sterling | ||||

| Today part of | | ||||

| ¹ Dutch was the sole official language until 1806, when the British officially replaced Dutch with English. Dutch was reincluded as a second official language in 1882. ² Except for the exclave of Walvis Bay, which is now part of Namibia. | |||||

The Cape Colony, established as a commandment and later governorate of the Dutch East India Company in 1652, was first occupied by the British in 1795, after the Battle of Muizenberg. Although the colony was handed back to the Dutch at the Peace of Amiens in 1802, the British re-occupied the colony with the Battle of Blaauwberg, after the Napoleonic Wars had started. The cession of the colony was subsequently affirmed in the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814.

The Cape Colony subsequently remained in the British Empire, becoming self-governing in 1872, and united with three other colonies to form the Union of South Africa in 1910, when it was renamed the Cape of Good Hope Province.[3] South Africa became fully independent in 1931 by the Statute of Westminster.

The Cape Colony was coextensive with the later Cape Province, stretching from the Atlantic coast inland and eastward along the southern coast, constituting about half of modern South Africa: the final eastern boundary, after several wars against the Xhosa, stood at the Fish River. In the north, the Orange River, also known as the Gariep River, served for a long time as the boundary, although some land between the river and the southern boundary of Botswana was later added to it.

History

Dutch Colonisation

Dutch East India Company (VOC) traders, under the command of Jan van Riebeeck, were the first people to establish a European colony in South Africa. The Cape settlement was built by them in 1652 as a re-supply point and way-station for Dutch East India Company vessels on their way back and forth between the Netherlands and Batavia (Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies. The support station gradually became a settler community, the forebears of the Afrikaners, a European ethnic group in South Africa.

The local Khoikhoi had neither a strong political organisation nor an economic base beyond their herds. They bartered livestock freely to Dutch ships. As Company employees established farms to supply the Cape station, they began to displace the Khoikhoi. Conflicts led to the consolidation of European landholdings and a breakdown of Khoikhoi society. Military success led to even greater Dutch East India Company control of the Khoikhoi by the 1670s. The Khoikhoi became the chief source of colonial wage labour.

After the first settlers spread out around the Company station, nomadic European livestock farmers, or Trekboeren, moved more widely afield, leaving the richer, but limited, farming lands of the coast for the drier interior tableland. There they contested still wider groups of Khoikhoi cattle herders for the best grazing lands. By 1700, the traditional Khoikhoi lifestyle of pastoralism had disappeared. By the time of British rule after 1795, the sociopolitical foundations were firmly laid.

The British Conquest

In 1795, France occupied the Seven Provinces of the Netherlands, the mother country of the Dutch East India Company. This prompted Great Britain to occupy the territory in 1795 as a way to better control the seas in order stop any potential French attempt to get to India. The British sent a fleet of nine warships which anchored at Simons Town and, following the defeat of the Dutch militia at the Battle of Muizenberg, took control of the territory. The Dutch East India Company transferred its territories and claims to the Batavian Republic (the Revolutionary period Dutch state) in 1798, and ceased to exist in 1799. Improving relations between Britain and Napoleonic France, and its vassal state the Batavian Republic, led the British to hand the Cape Colony over to the Batavian Republic in 1803 (under the terms of the Treaty of Amiens).

| Cape Colony History |

|---|

| Pre-1806 |

| 1806–1870 |

| 1870–1899 |

| 1899–1910 |

In 1806, the Cape, now nominally controlled by the Batavian Republic, was occupied again by the British after their victory in the Battle of Blaauwberg. The temporary peace between Britain and Napoleonic France had crumbled into open hostilities, whilst Napoleon had been strengthening his influence on the Batavian Republic (which Napoleon would subsequently abolish later the same year). The British, who set up a colony on 8 January 1806,[citation needed] hoped to keep Napoleon out of the Cape, and to control the Far East trade routes. In 1814 the Dutch government formally ceded sovereignty over the Cape to the British, under the terms of the Convention of London.

British Colonisation

The British started to settle the eastern border of the colony, with the arrival in Port Elizabeth of the 1820 Settlers. They also began to introduce the first rudimentary rights for the Cape's Black African population and, in 1833, abolished slavery. The resentment that the Dutch farmers felt against this social change, as well as the imposition of English language and culture, caused them to trek inland en masse. This was known as the Great Trek, and the migrating Afrikaners settled inland, forming the "Boer republics" of Transvaal and the Orange Free State.

British immigration continued in the Cape, even as many of the Afrikaners continued to trek inland, and the ending of the British East India Company's monopoly on trade led to economic growth. At the same time, the long series of border wars fought against the Xhosa people of the Cape's eastern frontier finally died down when the Xhosa partook in a mass destruction of their own crops and cattle, in the belief that this would cause their spirits to appear and defeat the whites. The resulting famine crippled Xhosa resistance and ushered in a long period of stability on the border.

Peace and prosperity led to a desire for political independence. In 1854, the Cape Colony elected its first parliament, on the basis of the multi-racial Cape Qualified Franchise. Cape residents qualified as voters based on a universal minimum level of property ownership, regardless of race.

Nonetheless, executive power remained completely in the hands of the British Governor and the colony was stricken with tensions between its eastern and western halves.[4]

Responsible Government

In 1872, after a long political battle, the Cape Colony achieved "Responsible Government" under its first Prime Minister, John Molteno. Henceforth, an elected Prime Minister and his cabinet had total responsibility for the affairs of the country. A period of strong economic growth and social development ensued, and the eastern-western division was largely laid to rest. The system of multi-racial franchise also began a slow and fragile growth in political inclusiveness, and ethnic tensions subsided.[5] In 1877, the state expanded by annexing Griqualand West and Griqualand East.[6]

However, the discovery of diamonds around Kimberley and gold in the Transvaal led to a return to instability, particularly because they fuelled the rise to power of the ambitious colonialist Cecil Rhodes. On becoming the Cape's Prime Minister, he instigated a rapid expansion of British influence into the hinterland. In particular, he sought to engineer the conquest of the Transvaal, and although his ill-fated Jameson Raid failed and brought down his government, it led to the Second Boer War and British conquest at the turn of the century. The politics of the colony consequently came to be increasingly dominated by tensions between the British colonists and the Afrikaners. Cecil Rhodes also brought in the first formal restrictions on the political rights of the Cape Colony's Black African citizens.[7]

The Cape Colony remained nominally under British rule until the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, when it became the Cape of Good Hope Province, better known as the Cape Province.

Governors of the Cape Colony (1797–1910)

British occupation (1st, 1797–1803)

- George Macartney, 1st Earl Macartney (1797–1798)

- Francis Dundas (1st time) (acting) (1798–1799)

- Sir George Yonge (1799–1801)

- Francis Dundas (2nd time) (acting) (1801–1803)

Batavian Republic (Dutch colony) (1803–1806)

- Jacob Abraham Uitenhage de Mist (1803–1804)

- Jan Willem Janssens (1803–1806)

British occupation (2nd, 1806–1814)

- Sir David Baird (acting) (1806–1807)

- Henry George Grey (1st time) (acting) (1807)

- Du Pre Alexander, 2nd Earl of Caledon (1807–1811)

- Henry George Grey (2nd time) (acting) (1811)

- Sir John Francis Cradock (1811–1814)

- Robert Meade (acting for Cradock) (1813–1814)

British colony (1814–1910)

_Bartle_Frere%2C_1st_Bt_by_Sir_George_Reid.jpg)

- Charles Somerset (1814–1826)

- Sir Rufane Shaw Donkin (acting for Somerset) (1820–1821)

- Richard Bourke (acting) (1826–1828)

- Sir Galbraith Lowry Cole (1828–1833)

- Thomas Francis Wade (acting for D'Urban from 10 Jan 1834) (1833–1834)

- Benjamin d'Urban (1834–1838)

- Sir George Thomas Napier (1838–1844)

- Sir Peregrine Maitland (1844–1847)

- Sir Henry Pottinger (1847)

- Sir Harry Smith (1847–1852)

- George Cathcart (1852–1854)

- Charles Henry Darling (acting) (1854)

- Sir George Grey (1854–1861)

- Robert Henry Wynyard (1st time) (acting for Grey) (1859–1860)

- Robert Henry Wynyard (2nd time) (acting) (1861–1862)

- Sir Philip Edmond Wodehouse (1862–1870)

- Charles Craufurd Hay (acting) (1870)

- Sir Henry Barkly (1870–1877)

- Henry Bartle Frere (1877–1880)

- Henry Hugh Clifford (acting) (1880)

- Sir George Cumine Strahan (acting) (1880–1881)

- Hercules Robinson (1st time) (1881–1889)

- Sir Leicester Smyth (1st time) (acting for Robinson) (1881)

- Sir Leicester Smyth (2nd time) (acting for Robinson) (1883–1884)

- Sir Henry D'Oyley Torrens (acting for Robinson) (1886)

- Henry Augustus Smyth (acting) (1889)

- Henry Brougham Loch (1889–1895)

- Sir William Gordon Cameron (1st time) (acting for Loch) (1891–1892)

- Sir William Gordon Cameron (2nd time) (acting for Loch) (1894)

- Hercules Robinson (2nd time) (1895–1897)

- Sir William Howley Goodenough (acting) (1897)

- Alfred Milner (1897–1901)

- Sir William Francis Butler (acting for Milner) (1898–1899)

- Sir Walter Hely-Hutchinson (1901–1910)

- Sir Henry Jenner Scobell (acting for Hely-Hutchinson) (1909)

The post of High Commissioner for Southern Africa was also held from 27 January 1847 to 31 May 1910 by the Governor of the Cape Colony. The post of Governor of the Cape Colony became extinct on 31 May 1910, when it joined the Union of South Africa.

Prime Ministers of the Cape Colony (1872–1910)

| No. | Name | Party | Assumed office | Left office |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sir John Charles Molteno | Independent | 1 December 1872 | 5 February 1878 |

| 2 | Sir John Gordon Sprigg | Independent | 6 February 1878 | 8 May 1881 |

| 3 | Thomas Charles Scanlen | Independent | 9 May 1881 | 12 May 1884 |

| 4 | Thomas Upington | Independent | 13 May 1884 | 24 November 1886 |

| — | Sir John Gordon Sprigg (2nd time) | Independent | 25 November 1886 | 16 July 1890 |

| 5 | Cecil John Rhodes | Independent | 17 July 1890 | 3 May 1893 |

| — | Cecil John Rhodes (2nd time) | Independent | 4 May 1893 | 12 January 1896 |

| — | Sir John Gordon Sprigg (3rd time) | Independent | 13 January 1896 | 13 October 1898 |

| 6 | William Philip Schreiner | Independent | 13 October 1898 | 17 June 1900 |

| — | Sir John Gordon Sprigg (4th time) | Progressive Party | 18 June 1900 | 21 February 1904 |

| 7 | Leander Starr Jameson | Progressive Party | 22 February 1904 | 2 February 1908 |

| 8 | John Xavier Merriman | South African Party | 3 February 1908 | 31 May 1910 |

The post of prime minister of the Cape Colony also became extinct on 31 May 1910, when it joined the Union of South Africa.

See also

- Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope

- Cape Colonial Forces

- Cape Government Railways

- Cape Qualified Franchise

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Alexander Wilmot; John Centlivres Chase (1869). History of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope: From Its Discovery to the Year 1819. J. C. Juta. pp. 268–. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ↑ "Census of the colony of the Cape of Good Hope. 1865". HathiTrust Digital Library. p. 11. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ Statemans Year Book, 1920, section on Cape Province

- ↑ Illustrated History of South Africa. The Reader's Digest Association South Africa (Pty) Ltd, 1992. ISBN 0-947008-90-X.

- ↑ Parsons, Neil, A New History of Southern Africa, Second Edition. Macmillan, London (1993)

- ↑ John Dugard: International Law, A South African Perspective. Cape Town. 2006. p.136.

- ↑ Ziegler, Philip (2008). Legacy: Cecil Rhodes, the Rhodes Trust and Rhodes Scholarships. Yale: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11835-3.

Sources

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Cape Colony. |

- Beck, Roger B. (2000). The History of South Africa. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 0-313-30730-X.

- Davenport, T. R. H., and Christopher Saunders (2000). South Africa: A Modern History, 5th ed. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-23376-0.

- Elbourne, Elizabeth (2002). Blood Ground: Colonialism, Missions, and the Contest for Christianity in the Cape Colony and Britain, 1799–1853. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2229-8.

- Le Cordeur, Basil Alexander (1981). The War of the Axe, 1847: Correspondence between the governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Henry Pottinger, and the commander of the British forces at the Cape, Sire George Berkeley, and others. Brenthurst Press. ISBN 0-909079-14-5.

- Mabin, Alan (1983). Recession and its aftermath: The Cape Colony in the eighteen eighties. University of the Witwatersrand, African Studies Institute. ASIN B0007C5VKA

- Ross, Robert, and David Anderson (1999). Status and Respectability in the Cape Colony, 1750–1870 : A Tragedy of Manners. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62122-4.

- Theal, George McCall (1970). History of the Boers in South Africa; Or, the Wanderings and Wars of the Emigrant Farmers from Their Leaving the Cape Colony to the Acknowledgment of Their Independence by Great Britain. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-8371-1661-9.

- Van Der Merwe, P.J., Roger B. Beck (1995). The Migrant Farmer in the History of the Cape Colony. Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8214-1090-3.

- Worden, Nigel, Elizabeth van Heyningen, and Vivian Bickford-Smith (1998). Cape Town: The Making of a City. Cape Town: David Philip. ISBN 0-86486-435-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cape Colony. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||