Brent Spar

Brent Spar or Brent E, was a North Sea oil storage and tanker loading buoy in the Brent oilfield, operated by Shell UK. With the completion of a pipeline connection to the oil terminal at Sullom Voe in Shetland, the storage facility had continued in use but was considered to be of no further value as of 1991. Brent Spar became an issue of public concern in 1995, when the British government announced its support for Shell's application for disposal in deep Atlantic waters at North Feni Ridge (approximately 250 km from the west coast of Scotland, at a depth of around 2.5 km).

Greenpeace organized a worldwide, high-profile media campaign against this plan. Greenpeace activists occupied the Brent Spar for more than three weeks. In the face of public and political opposition in northern Europe (including a widespread boycott of Shell service stations, some physical attacks and an arson attack on a service station in Germany), Shell abandoned its plans to dispose of Brent Spar at sea – whilst continuing to stand by its claim that this was the safest option, both from an environmental and an industrial health and safety perspective. Greenpeace's own reputation also suffered during the campaign, when it had to acknowledge that its assessment of the oil remaining in Brent Spar’s storage tanks had been grossly overestimated. Following Shell's decision to pursue only on-shore disposal options, as favoured by Greenpeace and its supporters, Brent Spar was given temporary moorings in a Norwegian fjord. In January 1998 Shell announced its decision to re-use much of the main structure in the construction of new harbour facilities near Stavanger, Norway.

Technical information

Brent "E" was a floating oil storage facility constructed in 1976 and moored approximately 2 km from the Brent "A" oil rig. It was jointly owned by Shell and Esso, and operated wholly by Shell, which gave them responsibility for decommissioning the structure. The Brent Spar was 147 m high and 29 m in diameter, and displaced 66,000 tonnes. The draft of the platform was such that manoeuvring in the North Sea south of Orkney was not possible. The storage tank section had a capacity of 50,000 tonnes (300,000 barrels) of crude oil. This section was built from 20 mm thick steel plate, reinforced by ribs and cross-braces. It was known that this section had been stressed and damaged on installation. This led to doubts on whether the facility would retain its structural integrity if it was refloated into a horizontal position.

Throughout the decommissioning process, Shell based its decisions on estimates of the quantities of various pollutants, including PCBs, crude oil, heavy metals and scale, which it had calculated based on the operating activities of the platform, and the quantity of metal that would remain in the structure after decommissioning was completed. Scale is a by-product of oil production, and because of the radioactivity found in the rocks from which the oil is extracted, is considered to be low-level radioactive waste. It is dealt with on-shore on a regular basis, by workers wearing breathing masks to prevent inhalation of dust.

Disposal options

Shell examined a number of options for disposing of the Brent Spar, and took two of these forward for serious consideration.

On-shore dismantling

The first option involved towing the Brent Spar to a shallow water harbour to decontaminate it and reuse the materials used in its construction. Any unusable waste could be disposed of on land. Technically, this option was more complex and presented a greater hazard to the workforce. This option was estimated to cost £41M. There was some concern that the facility would disintegrate in shallow coastal water, having a much more economically and environmentally significant impact.

Deep sea disposal

The second option involved towing the decommissioned platform into deep water in the North Atlantic, positioning explosives around the waterline, then detonating them, in order to breach the hull and sink the platform. The facility would then fall to the seabed and release its contents over a restricted area. Due to the uncertainty associated with detonating explosives, a number of possible scenarios were envisaged. First, the structure would fall to the seabed in one piece, releasing its contaminants slowly, and affecting the seabed for around 500 m "down-current". Second, the structure might disintegrate as it fell through the water column. This would release contaminants in a single burst, and have an effect for 1000 m "down current" of the final resting place, although this would last for a shorter time than in the first instance. Third, the structure could fail catastrophically when the explosives detonated, releasing its contaminants into the surface waters. This would have an impact on sea birds and on the fishing industry in that area. The cost of this option was estimated at between £17M and £20M.

Shell proposed that deep sea disposal was the best option for Brent Spar. Shell argued that their decision had been made on sound scientific principles and data. Dismantling the platform on-shore was more complex from an engineering point of view than disposal at sea. Shell also cited the lower risk to the health and safety of the workforce with deep sea disposal. Environmentally, Shell considered that sinking would have only a localised impact in a remote deep sea region which had little resource value. It was considered that this option would be acceptable to the public, to the United Kingdom Government and to regional authorities. Shell acknowledged that sinking the Brent Spar at sea was also the cheaper option.

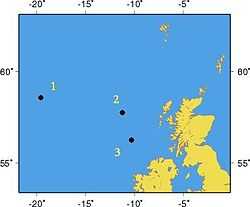

Having decided on a preferred method of disposal, Shell contracted Fisheries Research Services (FRS) to investigate possible sites for sinking the facility. There were two stipulations to this search: firstly, that the site was within British territorial waters, and secondly, that the site be deep enough that the sunken buoy would present no hazard to shipping. FRS identified three sites, as 20 km x 20 km squares, which were considered suitable. These were the Maury Channel, the North Feni Ridge and the Rockall Trough.

At these three sites, FRS carried out:

- seabed visualisation surveys using a remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) to confirm the topography in each area

- sediment sample collection using a box core sampler to analyse for heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), oil-related hydrocarbons and radionuclides

- investigations into particle size distribution, and total organic carbon levels of the sediment

- box core sampling to count the numbers of animals living in the sediment of the seabed

- beam trawl sampling to determine the different animals living on the seabed

The North Feni Ridge was found to include a narrow channel. The Rockall Trough area was found to be a gently sloping basin between the Anton Dohrn Seamount and the Wyville-Thomsom Ridge. The Maury Channel area was found to be a flat, gently sloping area.

Infaunal communities were found to be high in diversity and low in abundance, characteristic of unimpacted sediments. These communities were thought to have a limited food supply, which is also the norm in deep water communities.

The final conclusions of FRS were that abundance and diversity were greater than had been expected, especially in the North Feni Ridge area, however the limited extent of sampling precluded detailed analysis of data for the entire area. On the basis of the data which FRS gathered, there was little to choose between the three potential disposal areas. Analysis of the North Feni Ridge area may indicate that this area may have been accumulative, but that this would not preclude deep-sea disposal of the platform.

Having received these conclusions, Shell opted for the North Feni Ridge site, and applied to the British government for a licence to dispose of the rig at sea. This was approved in December 1994.

Greenpeace involvement

Greenpeace became aware of the plan to sink the Brent Spar at sea on 16 February 1995. The organization had been campaigning against ocean dumping in the North Sea since the early 1980s, using high-seas tactics to physically hinder the dumping of radioactive waste and waste from titanium dioxide production, and lobbying for a comprehensive ban on ocean dumping through the OSPAR convention.

Greenpeace objected to the plan to dispose of the Brent Spar at sea on a number of issues:

- That there was a lack of understanding of the deep sea environment, and therefore no way to predict the effects of the proposed dumping on deep sea ecosystems.

- The documents which supported Shell's licence application were "highly conjectural in nature", containing unsubstantiated assumptions, minimal data and extrapolations from unnamed studies.

- That dumping the Brent Spar at sea would create a precedent for dumping other contaminated structures in the sea and would undermine current international agreements. The environmental effects of further dumping would be cumulative.

- Dismantling of the Brent Spar was technically feasible and offshore engineering firms believed they could do it safely and effectively. The necessary facilities were already routinely in use and decommissioning of many other oil installations had already been carried out elsewhere in the world.

- To protect the environment, the principle of minimizing the generation of wastes should be upheld and harmful materials always recycled, treated or contained.

Greenpeace alleged that the scientific arguments for ocean dumping were being used as a way of disguising Shell's primary aim: to cut costs.

The "battle" of Brent Spar

Four Greenpeace activists first occupied Brent Spar on 30 April 1995. In total, 25 activists, photographers and journalists were involved in this stage of occupation. They chose to cover up the Exxon logos on the platform.[citation needed] At this time, activists collected a sample of the contents of the Brent Spar and sent it for testing to determine the nature of the pollutants which the platform contained. This sample was collected incorrectly, leading to a large overestimate in the contents of the facility. Although Greenpeace quoted Shell's own estimate of the amount of heavy metals and other chemicals on board, they claimed there were more than 5,500 tonnes of oil on the Spar – far more than Shell's estimate of 50 tonnes. For context, the Exxon Valdez oil spill involved around 42,000 tonnes.

Greenpeace mounted an energetic media campaign that influenced public opinion against Shell's preferred option. It disputed Shell's estimates of the contaminants on the Brent Spar, saying that these were much more than initially estimated. On 9 May, the German government issued a formal objection to the British government, with respect to the dumping plan. On 23 May, after several attempts, Shell obtained legal permission to evict the Greenpeace protesters from the Brent Spar, and they were eventually taken by helicopter to Aberdeen, Scotland, where they held a press conference.

Towing of the platform to its final position began on 11 June. By this time the call for a boycott of Shell products was being heeded across much of continental northern Europe, damaging Shell's profitability as well as brand image. German Chancellor Helmut Kohl protested to the British Prime Minister, John Major at a G7 conference in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Support from within the oil industry was not unanimous. Although oil production companies supported Shell's position, influential companies in the offshore construction sector stood to make money from onshore dismantling if a precedent could be set, and consequently supported the Greenpeace point of view.[citation needed]

On 20 June, Shell had decided that due to falling sales and a drop in share price, their position was no longer tenable, and withdrew their plan to sink the Brent Spar. They released the following statement:

"Shell's position as a major European enterprise has become untenable. The Spar had gained a symbolic significance out of all proportion to its environmental impact. In consequence, Shell companies were faced with increasingly intense public criticism, mostly in Continental northern Europe. Many politicians and ministers were openly hostile and several called for consumer boycotts. There was violence against Shell service stations, accompanied by threats to Shell staff."

In early July, the Norwegian government gave Shell permission to mothball the Brent Spar in Erfjord. It remained there for several years while other options for disposal were considered.

Aftermath

| Contaminant | Shell Co est. (kg) | DNV audit est. (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| PCBs | trace | 6.5 - 8.0 |

| Hydrocarbons | 50,700 | 75,000 - 100,000 |

| Aluminium | 28,677 | 24,000 - 40,000 |

| Arsenic | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Bismuth | 29.0 | 0.0 |

| Cadmium | 16.4 | 1.0-3.8 |

| Copper | 13,542.9 | 7,500 - 13,200 |

| Indium | 10.2 | 5.0 - 21.0 |

| Lead | 9.5 | 0.11 |

| Mercury | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Nickel | 7.4 | 0.9 - 1.5 |

| Silicon | 48.0 | 0.0 |

| Titanium | 8.8 | 0.0 |

| Zinc | 13,811.4 | 5,200 - 8,300 |

| Scale | 30,000 | 7800 - 9400 |

Having moored the Brent Spar in Erfjord, Shell commissioned the independent Norwegian consultancy Det Norske Veritas (DNV) to conduct an audit of Spar's contents and investigate Greenpeace's allegations. Greenpeace admitted that its claims that the Spar contained 5500 tonnes of oil were inaccurate and apologized to Shell on 5 September. This pre-empted the publication of DNV's report, which endorsed Shell's initial estimates for many pollutants. Greenpeace noted that its opposition to the dumping had never been solely based on the presence or absence of oil, however, and that opposition to the disposal plan was part of a larger campaign opposing the dumping of all waste into the North Sea.[citation needed]

Shell received over 200 individual suggestions for what could be done with the Brent Spar. One of these came from the Stavanger Port Authority. They were planning a quay extension at Mekjarvik, to provide new Roll-On/Roll-Off ferry facilities. It was hoped that using slices of the Spar's hull would save both money and energy that would otherwise have been spent in new steel construction. The Spar was raised vertically in the water by building a lifting cradle, placed underneath the Spar and connected by cables to jacks on board heavy barges. Jacking the cables upwards raised the Spar so that its hull could be cut into 'rings' and slid onto a barge.

After cleaning, the rings were placed in the sea beside the existing quay at Mekjarvik and filled with ballast. The construction of the quay extension was completed by placing a concrete slab across the rings. The Spar's living quarters and operations module, were removed and scrapped onshore at a Norwegian landfill site.

While the Brent Spar was being dismantled, quantities of the endangered cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa were found growing on the legs of the platform . At the time this was considered unusual, although recent studies have shown this to be a common occurrence, with 13 of 14 North Sea oil rigs examined having L. pertusa colonies. The authors of the original work suggested that it may be better to leave the lower parts of such structures in place – a suggestion opposed by Greenpeace who compared it to "[dumping] a car in a wood – moss would grow on it, and if I was lucky a bird may even nest in it. But this is not justification to fill our forests with disused cars".

Impact of Brent Spar

According to a poll of 1000 adults carried out by Opinion Leader Research on behalf of Greenpeace, as of 26 January 1996, a majority of the British public were aware of the Brent Spar (57%). Of these, 57% were opposed to the dumping of Brent Spar in the Atlantic, and 32% were in favour of it.

Although Shell had carried out an environmental impact assessment in full accordance with existing legislation, and firmly believed that their actions were in the best interests of the environment, they had severely underestimated strength of public opinion. Shell were particularly criticised for having thought of this as a "Scottish", or "UK" problem, and neglecting to think of the impact which it would have on their image in the wider world. The final cost of the Brent Spar operation to Shell was between £60M and £100M, when loss of sales were considered. Although Shell and the offshore industry consider that Brent Spar did not set a precedent for disposal of facilities in the future, signatory nations of the OSPAR conventions have since agreed that oil facilities should be disposed of onshore, so it is difficult to see how this does not set a precedent. Shell claimed that spending such an amount to protect a small area of remote, low resource value, deep sea was pointless and this money could be much more constructively spent.

The overestimation of the contents of the Brent Spar damaged the credibility of Greenpeace in their wider campaigns. They were criticised in an editorial column in the scientific journal Nature for their lack of interest in facts. Greenpeace moved to distance itself from its "5500 tonnes" claim, after the Brent Spar argument was won, and because of this has been accused of indulging in historical revisionism, after issuing statements such as "In the absence of a full inventory, Greenpeace, during our occupation, attempted to find out what was on the Brent Spar. The estimates resulting from this sampling were in no way central to the campaign...". This allegation has also been levelled at individuals, such as Lord Melchett, executive director of Greenpeace UK, who wrote in New Scientist magazine, "Greenpeace made mistakes too. We allowed ourselves to follow the agenda set by the Department of Trade and Industry, Shell and the media – too often getting into arguments about the potential toxicity of the Spar.".

Timeline

- 1976: Brent Spar built and enters service

- September 1991: Brent Spar ceases operations

- 1991–93: Shell examines options and carries out risk assessment and environmental impact assessment. Decides to sink Brent Spar at the North Feni Ridge.

- February 1994: Independent environmental consultancy, Aberdeen University Research and Industrial Services, endorses choice of deep sea disposal. Shell begins formal consultations with conservation bodies and fishing interests. Draft Abandonment Plan submitted.

- December 1994: UK government approves plans for sinking.

- April–May 1995: Greenpeace activists occupy platform to prevent sinking. Greenpeace International organizes boycott of Shell products and services.

- 30 April 1995: Greenpeace wrongly asserts that the Brent Spar still contains 5500 tonnes of crude oil.

- 5 May 1995: British Government grants disposal license to Shell UK.

- 9 May 1995: German Ministry of the Environment protests against disposal plan.

- 11 June 1995: Shell UK begins to tow Spar to deep Atlantic disposal site.

- 15 June 1995: German chancellor Helmut Kohl protests to British Prime Minister John Major at G7 summit.

- 14 June 1995 – 20 June 1995: Protesters in Germany threaten to damage 200 Shell service stations. 50 are subsequently damaged, two fire-bombed and one raked with bullets.

- 26 June 1995 – 30 June 1995: Eleven states call for a moratorium on sea disposal of decommissioned offshore installations at meeting of Oslo and Paris Commissions. Opposed by Britain and Norway.

- 7 July 1995: Norway grants permission to moor Spar in Erfjord while Shell reconsiders options.

- 12 July 1995: Shell UK commissions independent Norwegian consultancy Det Norske Veritas (DNV) to conduct an audit of Spar's contents and investigate Greenpeace allegations.

- 5 September 1995: Greenpeace admits inaccurate claims that Spar contains 5,550 tonnes of oil and apologizes to Shell.

- 18 October 1995 - DNV present results of their audit, endorsing the original Spar inventory. DNV state that the amount of oil claimed by Greenpeace to be in the Spar was "grossly overestimated".

- 29 January 1998: Shell announces Brent Spar will be disposed of on shore and used as foundations for a new ferry terminal.

- 23 July 1998: OSPAR member states announce agreement on onshore disposal of oil facilities in the future.

- February 1999: BBC 9 O'Clock News screens interview with Conservative former environment minister John Selwyn-Gummer in which he accuses Greenpeace campaigners of telling lies and, as a result, causing damage to the whole environmental movement.

- 10 July 1999: Decommissioning is completed and the first stages of constructing the ferry terminal are started.

- 25 November 1999: BBC formally apologizes to Greenpeace over screening of Gummer allegations.

Helicopter crash

- On 25 July 1990 a British International Helicopters Sikorsky S-61 registration 'G-BEWL' coming in from Sumburgh Airport crashed onto the platform as the pilots were attempting to land. The Sikorsky fell into the North Sea where six of the 13 passengers and crew onboard died.

References

- ^ Anon. (1996). "Structural damage danger for Brent Spar". Chemical Engineer (London) 7: 615–616.

- ^ "The Story". Shell's initial consideration of decommissioning ideas. Retrieved 10 March 2005.

- ^ "Case study: Brent Spar" (PDF). Details of the Fisheries Research Services analysis of the 3 possible disposal sites. Retrieved 10 March 2005.

- Owen, P. & Rice, T. (1999). Decommissioning of Brent Spar. Spon Press. ISBN 0-419-24090-X.

- ^ "DNV Inventory". Contents of Brent Spar, relative to quantities in the North Sea, as detailed by Det Norske Veritas. Retrieved 10 March 2005.

- ^ Woodham, A. (1999). "Dismantling of Brent Spar". Marine Pollution Bulletin 38 (2): 67. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(99)90003-6.

- ^ "Brent Spar Gets Chop". BBC News, World, Europe, Brent Spar Gets Chop. 25 November 1998. Retrieved 10 March 2005.

- ^ Anon. (1999). "Brent Spar Outcry Leaves Shell With A 60 m Pound Bill". Professional Engineering 12 (16): 9.

- ^ Editorial comment (1995). "Brent Spar, broken spur". Nature 375 (6534): 708–709. doi:10.1038/375708a0.

- ^ Melchett, P. (23 December 1995). "Green for Danger". New Scientist 148 (2010): 50–51.

- ^ "Oil rig home to rare coral". BBC News, Sci/Tech, Oil rig home to rare coral. 8 December 1999. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- ^ Bell, N. & Smith, J. (1999). "Coral growing on North Sea oil rigs". Nature 402 (6762): 601–2. doi:10.1038/45127. PMID 10604464.

- ^ Gass, S. & Roberts, J.M. (2006). "The occurrence of the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa (Scleractinia) on oil and gas platforms in the North Sea : Colony growth, recruitment and environmental controls on distribution". Marine pollution bulletin 52 (5): 549–559. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.10.002. PMID 16300800.http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=17830117

- ^ "Aircraft accident report 2/91". Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Appendices". Retrieved 20 November 2012.

External links

- Greenpeace History of the Brent Spar

- Brent Spar at the BBC

- Planetfilm Documentary film about Brent Spar

- Image: The Greenpeace activists celebrating in Aberdeen

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||