Box topology

In topology, the cartesian product of topological spaces can be given several different topologies. One of the more obvious choices is the box topology, where a base is given by the Cartesian products of open sets in the component spaces.[1] Another possibility is the product topology, where a base is given by the Cartesian products of open sets in the component spaces, only finitely many of which cannot equal the entire component space.

While the box topology has a somewhat more intuitive definition than the product topology, it satisfies fewer desirable properties. In particular, if all the component spaces are compact, the box topology on their Cartesian product will not necessarily be compact, although the product topology on their Cartesian product will always be compact. In general, the box topology is finer than the product topology, although the two agree in the case of finite direct products (or when all but finitely many of the factors are trivial).

Definition

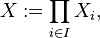

Given  such that

such that

or the (possibly infinite) Cartesian product of the topological spaces  , indexed by

, indexed by  , the box topology on

, the box topology on  is generated by the base

is generated by the base

The name box comes from the case of Rn, the basis sets look like boxes or unions thereof.

Properties

Box topology on Rω:[2]

- The box topology is completely regular

- The box topology is not first countable (hence not metrizable)

- The box topology is not separable

- The box topology is paracompact (and hence normal and completely regular) if the continuum hypothesis is true

Example - Failure at continuity

The following example is based on the Hilbert cube. Let Rω denote the countable cartesian product of R with itself, i.e. the set of all sequences in R. Equip R with the standard topology and Rω with the box topology. Let f : R → Rω be the product map whose components are all the identity, i.e. f(x) = (x, x, x, ...). Although each component function is continuous, f is not continuous. To see this, consider the open set U = Π∞

n=1(-1⁄n ,1⁄n). Since f(0) = (0, 0, 0, ...)∈U, if f were continuous, then there would exist some ε>0 such that (-ε, ε)∈f−1(U). But this would imply that f(ε⁄2)=(ε⁄2, ε⁄2, ε⁄2, ...)∈U which is false since ε⁄2 > 1⁄n for n > ⌈2⁄ε⌉. Thus f is not continuous even though all its component functions are.

Example - Failure at compactness

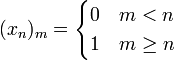

Consider the countable product  where for each i,

where for each i,  with the discrete topology. The box topology on

with the discrete topology. The box topology on  will also be the discrete topology. Consider the sequence

will also be the discrete topology. Consider the sequence  given by

given by

Since no two points in the sequence are the same, the sequence has no limit point, and therefore  is not compact, even though its component spaces are.

is not compact, even though its component spaces are.

Intuitive Description of Convergence; Comparisons

Topologies are often best understood by describing how sequences converge. In general, a cartesian product of a space X with itself over an indexing set S is precisely the space of functions from S to X; the product topology yields the topology of pointwise convergence; sequences of functions converge if and only if they converge at every point of S. The box topology, once again due to its great profusion of open sets, makes convergence very hard. One way to visualize the convergence in this topology is to think of functions from R to R — a sequence of functions converges to a function f in the box topology if, when looking at the graph of f, given any set of "hoops", that is, vertical open intervals surrounding the graph of f above every point on the x-axis, eventually, every function in the sequence "jumps through all the hoops." For functions on R this looks a lot like uniform convergence, in which case all the "hoops", once chosen, must be the same size. But in this case one can make the hoops arbitrarily small, so one can see intuitively how "hard" it is for sequences of functions to converge. The hoop picture works for convergence in the product topology as well: here we only require all the functions to jump through any given finite set of hoops. This stems directly from the fact that, in the product topology, almost all the factors in a basic open set are the whole space. Interestingly, this is actually equivalent to requiring all functions to eventually jump through just a single given hoop; this is just the definition of pointwise convergence.

Comparison with product topology

The basis sets in the product topology have almost the same definition as the above, except with the qualification that all but finitely many Ui are equal to the component space Xi. The product topology satisfies a very desirable property for maps fi : Y → Xi into the component spaces: the product map f: Y → X defined by the component functions fi is continuous if and only if all the fi are continuous. As shown above, this does not always hold in the box topology. This actually makes the box topology very useful for providing counterexamples — many qualities such as compactness, connectedness, metrizability, etc., if possessed by the factor spaces, are not in general preserved in the product with this topology.

See also

Notes

References

- Steen, Lynn A. and Seebach, J. Arthur Jr.; Counterexamples in Topology, Holt, Rinehart and Winston (1970). ISBN 0030794854.

- Willard, Stephen (2004). General Topology. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43479-6.