Bouba/kiki effect

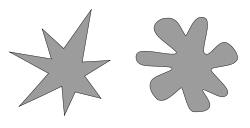

The bouba/kiki effect is a non-arbitrary mapping between speech sounds and the visual shape of objects. This effect was first observed by German-American psychologist Wolfgang Köhler in 1929.[1] In psychological experiments, first conducted on the island of Tenerife (in which the primary language is Spanish), Köhler showed forms similar to those shown at the right and asked participants which shape was called "takete" and which was called "baluba" ("maluma" in the 1947 version). Data suggested a strong preference to pair the jagged shape with "takete" and the rounded shape with "baluba".[2]

In 2001, Vilayanur S. Ramachandran and Edward Hubbard repeated Köhler's experiment using the words "kiki" and "bouba" and asked American college undergraduates and Tamil speakers in India "Which of these shapes is bouba and which is kiki?" In both groups, 95% to 98% selected the curvy shape as "bouba" and the jagged one as "kiki", suggesting that the human brain somehow attaches abstract meanings to the shapes and sounds in a consistent way.[3] Recent work by Daphne Maurer and colleagues shows that even children as young as 2.5 (too young to read) may show this effect as well.[4]

Ramachandran and Hubbard suggest that the kiki/bouba effect has implications for the evolution of language, because it suggests that the naming of objects is not completely arbitrary.[3] The rounded shape may most commonly be named "bouba" because the mouth makes a more rounded shape to produce that sound while a more taut, angular mouth shape is needed to make the sound "kiki". The sounds of a K are harder and more forceful than those of a B, as well. The presence of these "synesthesia-like mappings" suggest that this effect might be the neurological basis for sound symbolism, in which sounds are non-arbitrarily mapped to objects and events in the world.

More recently research indicated that the effect may be a case of ideasthesia.[5]

Individuals who have autism do not show as strong a preference. Where typically developing individuals agree with the standard result 88% of the time, individuals with autism agree only 56% of the time.[6]

References

- ↑ Köhler, W (1929). Gestalt Psychology. New York: Liveright.

- ↑ Köhler, W (1947). Gestalt Psychology, 2nd Ed. New York: Liveright.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ramachandran, VS & Hubbard, EM (2001b). "Synaesthesia: A window into perception, thought and language". Journal of Consciousness Studies 8 (12): 3–34.

- ↑ Maurer D, Pathman T & Mondloch CJ (2006). "The shape of boubas: Sound-shape correspondences in toddlers and adults". Developmental Science 9 (3): 316–322. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00495.x. PMID 16669803.

- ↑ Gómez Milán, E., Iborra, O., de Córdoba, M.J., Juárez-Ramos V., Rodríguez Artacho, M.A., Rubio, J.L. (2013) The Kiki-Bouba effect: A case of personification and ideaesthesia. The Journal of Consciousness Studies. 20(1-2): pp. 84-102.

- ↑ Oberman LM & Ramachandran VS. (2008). "Preliminary evidence for deficits in multisensory integration in autism spectrum disorders: the mirror neuron hypothesis". Social Neuroscience 3 (3-4): 348–55. doi:10.1080/17470910701563681. PMID 18979385.