Boletus calopus

| Boletus calopus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Boletales |

| Family: | Boletaceae |

| Genus: | Boletus |

| Species: | B. calopus |

| Binomial name | |

| Boletus calopus Pers. (1801) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

| Boletus calopus | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| pores on hymenium | |

| cap is convex | |

| hymenium is adnate | |

| stipe is bare | |

| spore print is olive-brown | |

| ecology is mycorrhizal | |

| edibility: inedible | |

Boletus calopus, commonly known as the bitter beech bolete or scarlet-stemmed bolete, is a fungus of the bolete family, found in Asia, Northern Europe and North America. Appearing in coniferous and deciduous woodland in summer and autumn, the stout fruit bodies are attractively coloured, with a beige to olive cap up to 15 cm (6 in) across, yellow pores, and a reddish stipe up to 15 cm (6 in) long and 5 cm (2 in) wide. The pale yellow flesh stains blue when broken or bruised.

Christian Persoon first described Boletus calopus in 1801. Modern molecular phylogenetics shows that it is only distantly related to the type species of Boletus and will most likely be placed in a new genus after further study. Boletus calopus is not edible, rendered unpalatable by its intensely bitter taste, which does not disappear with cooking. Its red stipe distinguishes it from edible species such as Boletus edulis.

Taxonomy

Boletus calopus was originally published under the name Boletus olivaceus by Jacob Christian Schäffer in 1774,[2] but this name is unavailable for use as it was later sanctioned for another species.[3] Johann Friedrich Gmelin's 1792 synonym Boletus lapidum[4] is also illegitimate.[5] Christian Hendrik Persoon described the mushroom in 1801;[6] its specific name is derived from the Greek καλος/kalos ("pretty") and πους/pous ("foot"), referring to its brightly coloured stipe. The German name, Schönfußröhrling or "pretty-foot bolete", is a literal translation. Alternate common names are scarlet-stemmed bolete[7] and bitter beech bolete.[8]

Other synonyms include binomials resulting from generic transfers to Dictyopus by Lucien Quélet in 1886,[9] and Tubiporus by René Maire in 1937.[10] Boletus frustosus, originally published as a distinct species by Wally Snell and Esther Dick in 1941,[11] was later described as a variety of B. calopus by Orson K. Miller and Roy Watling in 1968.[12] Estadès and Lannoy described the variety ruforubraporus and the form ereticulatus from Europe in 2001.[13]

In his 1986 infrageneric classification of the genus Boletus, Rolf Singer placed B. calopus as the type species of the section Calopodes, which includes species characterised by having a whitish to yellowish flesh, bitter taste, and a blue staining reaction in the tube walls. Other species in section Calopodes include B. radicans, B. inedulis, B. peckii, and B. pallidus.[14] Genetic analysis published in 2013 shows that B. calopus and many (but not all) red-pored boletes are part of a dupainii clade (named for B. dupainii), well-removed from the core group of the type species B. edulis and relatives within the Boletineae. This indicates that it needs to be placed in a new genus.[15]

Description

.JPG)

Up to 15 cm (6 in) or rarely 20 cm (8 in) in diameter, the cap is beige to olive and initially almost globular before opening out to a hemispherical and then convex shape.[16] The surface of the cap is smooth or has minute hairs, and sometimes develops cracks with age.[17] The cap cuticle hangs over the cap margin.[18] The pore surface is initially pale yellow before deepening to an olive-yellow in maturity, and quickly turns blue when it is injured. The pores, numbering one or two per millimetre, are circular when young but become more angular as the mushroom ages. The tubes are up to 2 cm (0.8 in) deep.[19]

The attractively coloured stipe is typically yellow above to pink-red below, with a straw-coloured network (reticulation) near the top or over the upper half;[19] occasionally the entire stipe is reddish.[17] It measures 7–15 cm (2.8–5.9 in) long by 2–5 cm (0.8–2.0 in) thick, and is either fairly equal in width throughout, or thicker towards the base.[19] Sometimes, the reddish stipe colour of mature mushrooms or harvested specimens that are a few days old disappears completely, and is replaced with ochre-brown tones.[20] The pale yellow flesh stains blue when broken, the discolouration spreading out from the damaged area.[21] Its smell can be strong, and has been likened to ink.[22] The spore print is olive to olive-brown. Spores are smooth and elliptical, measuring 13–19 by 5–6 µm.[19] The basidia (spore-bearing cells) are club-shaped, four-spored, and measure 30–38 by 9–12 µm. The cystidia are club-shaped to spindle-shaped, hyaline, and measure 25–40 by 10–15 µm.[20]

Variety frustosus is morphologically similar to the main type, but its cap becomes areolate (marked out into small areas by cracks and crevices) in maturity. Its spores are slightly smaller too, measuring 11–15 by 4–5.5 µm.[19] In the European form ereticulatus, the reticulations on the upper stipe are replaced with fine reddish granules, while the variety ruforubraporus has pinkish-red pores.[13]

Similar species

The overall colouration of Boletus calopus, with its pale cap, yellow pores and red stipe, is not shared with any other bolete.[23] Large pale specimens resemble Boletus luridus, and the cap of B. satanas is a similar colour but this species has red pores. Fruit bodies in poor condition could be confused with Xerocomellus chrysenteron but the stipes of this species are not reticulated.[21] Edible species such as B. edulis lack a red stipe.[16] It closely resembles the similarly inedible B. radicans, which lacks the redness on the stipe.[23] Like B. calopus, the western North American species B. rubripes also has a bitter taste, similarly coloured cap, and yellowish pores that bruise blue, but it lacks reticulation on its reddish stipe.[24] Found in northwestern North America, B. coniferarum lacks reddish or pinkish colouration in its yellow reticulate stipe, and has a darker, olive-grey to deep brown cap.[17]

Two eastern North American species, B. inedulis and B. roseipes, also have an appearance similar to B. calopus. B. inedulis produces smaller fruit bodies with a white to greyish-white cap, while B. roseipes associates solely with hemlock.[25] B. firmus, found in the eastern United States, eastern Canada, and Costa Rica, has a pallid cap colour, reddish stipe, and bitter taste, but unlike B. calopus, has red pores and lacks stipe reticulation.[26] B. panniformis, a Japanese species described as new to science in 2013, bears a resemblance to B. calopus, but can be distinguished by its rough cap surface, or microscopically by the amyloid-staining cells in the flesh of the cap, and morphologically distinct cystidia on the stipe.[27]

Distribution and habitat

An ectomycorrhizal species,[25] Boletus calopus grows in coniferous and deciduous woodland, often at higher altitudes, especially under beech and oak.[22] Fruit bodies occur singly or in large groups.[20] The species grows on chalky ground from July to December, in Northern Europe,[22] and North America's Pacific Northwest and Michigan.[28] In North America, its range extends south to Mexico.[29] Variety frustosus is known from California and the Rocky Mountains of Idaho.[19] In 1968, after comparing European and North American collections, Miller and Watling suggested that the typical form of B. calopus does not occur in the United States. Similar comparisons by other authors have led them to the opposite conclusion,[30] and the species has since been included in several North American field guides.[17][19][24] The bolete has been recorded from the Black Sea region in Turkey,[31] from under Populus ciliata and Abies pindrow in Rawalpindi and Nathia Gali in Pakistan,[32] Yunnan Province in China,[33] Korea,[34] and Taiwan.[35]

Toxicity

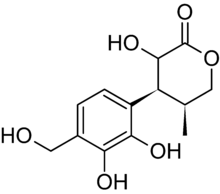

Although it is an attractive-looking bolete, Boletus calopus is not considered edible on account of its very bitter taste, which does not disappear upon cooking.[36] There are, however, reports of it being eaten in far eastern Russia as well as in Ukraine.[37] The bitter taste is largely due to the compounds calopin[38] and a δ-lactone derivative, O-acetylcyclocalopin A. These compounds contains a structural motif known as a 3-methylcatechol unit, which is rare in natural products. A total synthesis of calopin was reported in 2003.[39]

The pulvinic acid derivatives atromentic acid, variegatic acid, and xerocomic acid are present in B. calopus mushrooms. These compounds inhibit cytochrome P450—major enzymes involved in drug metabolism and bioactivation.[40] Other compounds found in the fruit bodies include calopin B,[41] and the novel sesquiterpenoid compounds cyclopinol[42] and boletunones A and B. The latter two highly oxygenated compounds have significant free-radical scavenging activity in vitro.[34] The compounds 3-octanone (47.0% of total volatile compounds), 3-octanol (27.0%), 1-octen-3-ol (15.0%), and limonene (3.6%) are the predominant volatile components that give the fruit body its odour.[43]

See also

References

- ↑ "Synonyms: Boletus calopus Pers., Syn. meth. fung. (Göttingen) 2: 513 (1801)". Species Fungorum. CAB International. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ↑ Schäffer, J.C. (1774). Fungorum qui in Bavaria et Palatinatu circa Ratisbonam nascuntur Icones (in Latin & German) 4. Erlangen, Germany: Apud J.J. Palmium. p. 77; plate 105.

- ↑ "Boletus olivaceus Schaeff., Fungorum qui in Bavaria et Palatinatu circa Ratisbonam nascuntur Icones, 4: 77, t. 105, 1774". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ↑ Gmelin, J.F. (1792). Systema Naturae (in Latin) 2 (13 ed.). Leipzig, Germany: G.E. Beer. p. 1434.

- ↑ "Boletus lapidum J.F. Gmel., Systema Naturae, 2: 1434, 1792". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ↑ Persoon, C.H. (1801). Synopsis methodica fungorum (in Latin). Göttingen, Sweden: Dieterich. p. 513.

- ↑ Lamaison, J.-L.; Polese, J.-M. (2005). The Great Encyclopedia of Mushrooms. Cologne, Germany: Könemann. p. 33. ISBN 978-3-8331-1239-3.

- ↑ Holden, E.M. (2003). "Recommended English Names for Fungi in the UK" (PDF). British Mycological Society.

- ↑ Quélet, L. (1886). Enchiridion Fungorum in Europa media et praesertim in Gallia Vigentium (in Latin). Paris, France: Octave Dion. p. 160.

- ↑ Maire, R. (1937). "Fungi Catalaunici: Series altera. Contributions a l'étude de la flore mycologique de la Catalogne". Publicacions del Instituto Botánico Barcelona (in French) 3 (4): 1–128 (see p. 46).

- ↑ Snell, W.H.; Dick, E.A. (1941). "Notes on Boletes. VI". Mycologia 33: 23–37 (see p. 33). doi:10.2307/3754732.

- ↑ Miller, O.K. Jr.; Watling, R. (1968). "The status of Boletus calopus Fr. in North America". Notes From the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh 28: 317–26.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Estadès, A.; Lannoy, G. (2001). "Boletaceae – Validations diverses". Documents Mycologiques (in French) 31 (121): 57–61.

- ↑ Singer, R. (1986). The Agaricales in Modern Taxonomy (4 ed.). Königstein im Taunus, Germany: Koeltz Scientific Books. p. 779. ISBN 978-3-87429-254-2.

- ↑ Nuhn, M.E.; Binder, M.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Halling, R.E.; Hibbett, D.S. (2013). "Phylogenetic overview of the Boletineae". Fungal Biology 117 (7–8): 479–511. doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2013.04.008.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Zeitlmayr, L. (1976). Wild Mushrooms: An Illustrated Handbook. Hertfordshire, UK: Garden City Press. pp. 104–05. ISBN 978-0-584-10324-3.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Arora, D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: A Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-89815-169-5.

- ↑ Laessoe, T. (2002). Mushrooms. Smithsonian Handbooks (2 ed.). London, UK: Dorling Kindersley Adult. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-7894-8986-9.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 Bessette, A.R.; Bessette, A.; Roody, W.C. (2000). North American Boletes: A Color Guide to the Fleshy Pored Mushrooms. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. pp. 100–01. ISBN 978-0-8156-0588-1.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Alessio, C.L. (1985). Boletus Dill. ex L. (sensu lato) (in Italian). Saronno, Italy: Biella Giovanna. pp. 153–56.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Haas, H. (1969). The Young Specialist looks at Fungi. London, UK: Burke. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-222-79409-3.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Nilson, S.; Persson, O. (1977). Fungi of Northern Europe 1: Larger Fungi (Excluding Gill-Fungi). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-14-063005-3.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Breitenbach, J.; Kränzlin, F. (1991). Fungi of Switzerland 3: Boletes & Agarics, 1st Part. Lucerne, Switzerland: Sticher Printing. p. 52. ISBN 978-3-85604-230-1.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Davis, R. Michael; Sommer, Robert; Menge, John A. (2012). Field Guide to Mushrooms of Western North America. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-520-95360-4.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Roberts, P.; Evans, S. (2011). The Book of Fungi. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-226-72117-0.

- ↑ Halling, R.; Mueller, G.M. (1999). "New boletes from Costa Rica". Mycologia 91 (5): 893–99. JSTOR 3761543.

- ↑ Takahashi, H.; Taneyama, Y.; Degawa, Y. (2013). "Notes on the boletes of Japan 1. Four new species of the genus Boletus from central Honshu, Japan". Mycoscience. doi:10.1016/j.myc.2013.02.005.

- ↑ Phillips, R. (2005). Mushrooms and Other Fungi of North America. Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-55407-115-9.

- ↑ Landeros, F.; Castillo, J.; Guzmán, G.; Cifuentes, J. (2006). "Los hongos (macromicetos) conocidos an at Cerro el Zamorano (Queretaro-Guanajuato), Mexico" [Known macromycetes from Cerro el Zamorano (Queretaro-Guanajuato), Mexico] (PDF). Revista Mexicana de Micologia (in Spanish) 22: 25–31.

- ↑ Thiers, H.D. (1998) [1975]. "Boletus calopus". The Boletes of California. New York, New York: Hafner Press; MykoWeb (online version).

- ↑ Sesli, E. (2007). "Preliminary checklist of macromycetes of the East and Middle Black Sea Regions of Turkey". Mycotaxon 99: 71–74.

- ↑ Sarwar, S.; Khalid, A.N. (2013). "Preliminary Checklist of Boletales in Pakistan". Mycotaxon: 1–12.

- ↑ Wang, L.; Song D.-S.; Liang, J-F.; Li, Y-C.; Zhang, Y. (2006). "Macrofungus resources and their utilization in Shangri-La County, Northwest in Yunnan Province". Journal of Plant Resources and Environment (in Chinese) 15 (3): 79–80. ISSN 1004-0978.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Kim, W.-G.; Kim, J.-W.; Ryoo, I.-J.; Kim, J.-P.; Kim, Y.-H.; Yoo, I.-D. (2004). "Boletunones A and B, highly functionalized novel sesquiterpenes from Boletus calopus". Organic Letters 6 (5): 823–26. doi:10.1021/ol049953i. PMID 14986984.

- ↑ Yeh, K.-W.; Chen, Z.-C. (1981). "The boletes of Tawian 2". Taiwania 26: 100–15. ISSN 0372-333X.

- ↑ Carluccio, A. (2003). The Complete Mushroom Book. London, UK: Quadrille. ISBN 978-1-84400-040-1.

- ↑ Boa, E.R. (2004). Wild Edible Fungi: A Global Overview Of Their Use And Importance To People. Non-Wood Forest Products 17. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. pp. 123, 128. ISBN 978-92-5-105157-3.

- ↑ Hellwig, V.; Dasenbrock, J.; Gräf, C.; Kahner, L.; Schumann, S.; Steglich, W. (2002). "Calopins and cyclocalopins – Bitter principles from Boletus calopus and related mushrooms". European Journal of Organic Chemistry 2002 (17): 2895–904. doi:10.1002/1099-0690(200209)2002:17<2895::AID-EJOC2895>3.0.CO;2-S.

- ↑ Ebel, H.; Knör, S.; Steglich, W. (2003). "Total synthesis of the mushroom metabolite (+)-calopin". Tetrahedron 59 (1): 123–29. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01451-5.

- ↑ Huang, Y.-T.; Onose, J.-I.; Abe, N.; Yoshikawa, K. (2009). "In vitro inhibitory effects of pulvinic acid derivatives isolated from Chinese edible mushrooms, Boletus calopus and Suillus bovinus, on cytochrome P450 activity" (PDF). Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry 73 (4): 855–60. doi:10.1271/bbb.80759. PMID 19352038.

- ↑ Kim, J.-W.; Yoo, I.-D.; Kim, W.-G. (2006). "Free radical-scavenging δ-lactones from Boletus calopus". Planta Medica 72 (15): 1431–32. doi:10.1055/s-2006-951722. PMID 17091435.

- ↑ Liu, D.-Z.; Wang, F.; Jia, R.-R.; Liu, J.-K. (2008). "A novel sesquiterpene from the basidiomycete Boletus calopus". Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B. A Journal of Chemical Sciences 63 (1): 114–16.

- ↑ Rapior, S.; Marion, C.; Pélissier, Y.; Bessière, J.-M. (1997). "Volatile composition of fourteen species of fresh wild mushrooms (Boletales)". Journal of Essential Oil Research 9 (2): 231–34. doi:10.1080/10412905.1997.9699468.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boletus calopus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Boletus calopus |