Body language

Body language refers to various forms of nonverbal communication, wherein a person may reveal clues as to some unspoken intention or feeling through their physical behaviour. These behaviours can include body posture, gestures, facial expressions, and eye movements. Although this article focuses on interpretations of human body language, also animals use body language as a communication mechanism. Body language is typically subconscious behaviour, and is therefore considered distinct from sign language, which is a fully conscious and intentional act of communication.

Body language may provide clues as to the attitude or state of mind of a person. For example, it may indicate aggression, attentiveness, boredom, a relaxed state, pleasure, amusement, and intoxication.

Body language is significant to communication and relationships. It is relevant to management and leadership in business and also in places where it can be observed by many people. It can also be relevant to some outside of the workplace. It is commonly helpful in dating, mating, in family settings, and parenting. Although body language is non-verbal or non-spoken, it can reveal much about your feelings and meaning to others and how others reveal their feelings toward you. Body language signals happen on both a conscious and unconscious level.[1]

Understanding body language

The technique of "reading" people is used frequently. For example, the idea of mirroring body language to put people at ease is commonly used during interview situations. Body language can show feelings to other people, which works in return for other people. People who show their body language to you can reveal their feelings and meanings. Mirroring the body language of someone else indicates that they are understood.[citation needed] It is important to note that some markers of emotion (e.g. smiling/laughing when happy, frowning/crying when sad) are largely universal,[2] however in the 1990s Paul Ekman expanded his list of basic emotions, including a range of positive and negative emotions, not all of which are encoded in facial muscles.[citation needed] The newly included emotions are:

- Amusement

- Contempt

- Contentment

- Embarrassment

- Excitement

- Guilt

- Pride in achievement

- Relief

- Satisfaction

- Sensory pleasure

- Shame

Body language signals may have a goal other than communication. People would keep both these two in mind. Observers limit the weight they place on non-verbal cues. Signalers clarify their signals to indicate the biological origin of their actions. Verbal communication also requires body language to show that the person you are talking with that you are listening. These signals can consist of; eye contact and nodding your head to show you understand. More examples would include yawning (sleepiness), showing lack of interest (sexual interest/survival interest), attempts to change the topic (fight or flight drivers). Rudolf Laban and Warren Lamb add much to this about dancers. Mime artists utilize these techniques to communicate entire shows without a single word.

Physical expression

Physical expressions like waving, pointing, touching and slouching are all forms of nonverbal communication. The study of body movement and expression is known as kinesics. Humans move their bodies when communicating because, as research has shown[citation needed], it helps "ease the mental effort when communication is difficult." Physical expressions reveal many things about the person using them. For example, gestures can emphasize a point or relay a message, posture can reveal boredom or great interest, and touch can convey encouragement or caution.[3]

- One of the most basic and powerful body-language signals is when a person crosses his or her arms across the chest.[4] This could indicate that a person is putting up an unconscious barrier between themselves and others. However, it can also indicate that the person's arms are cold, which would be clarified by rubbing the arms or huddling. When the overall situation is amicable, it can mean that a person is thinking deeply about what is being discussed, but in a serious or confrontational situation, it can mean that a person is expressing opposition. This is especially so if the person is leaning away from the speaker. A harsh or blank facial expression often indicates outright hostility.

- Consistent eye contact can indicate that a person is thinking positively of what the speaker is saying. It can also mean that the other person doesn't trust the speaker enough to "take their eyes off" the speaker. Lack of eye contact can indicate negativity. On the other hand, individuals with anxiety disorders are often unable to make eye contact without discomfort. Eye contact can also be a secondary and misleading gesture because cultural norms about it vary widely. If a person is looking at you, but is making the arms-across-chest signal, the eye contact could be indicative that something is bothering the person, and that he wants to talk about it. Or if while making direct eye contact, a person is fiddling with something, even while directly looking at you, it could indicate that the attention is elsewhere.[citation needed]

- Disbelief is often indicated by averted gaze, or by touching the ear or scratching the chin. When a person is not being convinced by what someone is saying, the attention invariably wanders, and the eyes will stare away for an extended period.[citation needed]

- Boredom is indicated by the head tilting to one side, or by the eyes looking straight at the speaker but becoming slightly unfocused. A head tilt may also indicate a sore neck, trust or a feeling of safety (part of the neck becomes uncovered, hence vulnerable; It's virtually impossible to tilt our head in front of someone we don't trust or are scared of) or Amblyopia, and unfocused eyes may indicate ocular problems in the listener.[citation needed]

- Interest can be indicated through posture or extended eye contact, such as standing and listening properly.[citation needed]

- Excessive blinking, or the absence of blinking, may be an indicator of lying.[5]

Some people use and understand body language differently.[citation needed] Interpreting their gestures and facial expressions (or lack thereof) in the context of normal body language usually leads to misunderstandings and misinterpretations (especially if body language is given priority over spoken language). It should also be stated that people from different cultures can interpret body language in different ways.

Prevalence of non-verbal communication in humans

James Borg states that human communication consists of 93 percent body language and paralinguistic clues, while only 7% of communication consists of words themselves;[6] however, Albert Mehrabian, the researcher whose 1960s work is the source of these statistics, has stated that this is a misunderstanding of the findings[7] (see Misinterpretation of Mehrabian's rule). Albert Mehrabian found "that the verbal component of a face-to-face conversation is less than 35% and that over 65% of communication is done non-verbally".[8]

The interpretation of body language should not be based on a single gesture. Pease (2004) suggests evaluation should be on three distinct rules: 1) Read gestures in clusters; 2) look for congruence; and 3) read gestures in context.

Proxemics

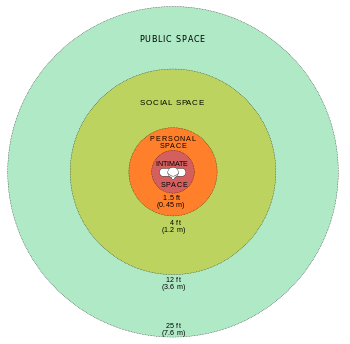

Introduced by Edward T. Hall in 1966, proxemics is the study of measurable distances between people as they interact with one another.[9] The distance between people in a social situation often discloses information about the type of relationship between the people involved. Proximity may also reveal the type of social setting taking place.

- Intimate distance ranges from touching to about 18 inches (46 cm) apart, and is reserved for lovers, children, as well as close family members and friends, and also pet animals.

- Personal distance begins about an arm's length away; starting around 18 inches (46 cm) from the person and ending about 4 feet (122 cm) away. This space is used in conversations with friends, to chat with associates, and in group discussions.

- Social distance ranges from 4 to 8 feet (1.2 m - 2.4 m) away from the person and is reserved for strangers, newly formed groups, and new acquaintances.

- Public distance includes anything more than 8 feet (2.4 m) away, and is used for speeches, lectures, and theater. Public distance is essentially that range reserved for larger audiences.[10]

Proximity range varies with culture.

Unintentional gestures

Beginning in the 1960s, there has been huge interest in studying human behavioral clues that could be useful for developing an interactive and adaptive human-machine system.[11] Unintentional human gestures such as making an eye rub, a chin rest, a lip touch, a nose itch, a head scratch, an ear scratch, crossing arms, and a finger lock have been found conveying some useful information in specific contexts. In poker games, such gestures are referred to as "tells" and are useful to players for detecting deception clues or behavioral patterns in opponents.

See also

- Calypsis

- Gesture

- Gesture recognition

- List of gestures

- Origin of language

- Origin of speech

- Posture (psychology)

- Paul Ekman

- Mirroring

References

- ↑ McCarthy, Sandra. "Body Language". Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ↑ Markku Haakana 2001. Laughing Matters: A Conversation Analytical Study of Laughter in Doctor - Patient Interaction. Department of Finnish Language, University of Helsinki

- ↑ Engleberg,Isa N. Working in Groups: Communication Principles and Strategies. My Communication Kit Series, 2006. page 137

- ↑ "Closed body language". Changingminds.org. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Post. "The Times | UK News, World News and Opinion". Timesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Borg, James. Body Language: 7 Easy Lessons to Master the Silent Language. FT Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-13-700260-3

- ↑ "More or Less". 2009-08-14. BBC Radio 4. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00lyvz9.

- ↑ Pease, A., & Pease, B. (2004). The Definitive Book of Body Language: How to read others' thoughts by their gestures. Buderim, Australia: Pease International.

- ↑ ^ Hall, Edward T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-08476-5

- ↑ Engleberg,Isa N. Working in Groups: Communication Principles and Strategies. My Communication Kit Series, 2006. page 140-141

- ↑ Pease, Allan (October 21, 2004). The Definitive guide to Body Language. Chapter 1: Orion Media. ISBN 0752861182.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Body language. |

- Body language is of particular importance in large groups by Tarnow, E. published 1997

- Hess Pupil Dilation Findings: Sex or Novelty? Social Behavior and Personality, 1998 by Aboyoun, Darren C, Dabbs, James M Jr

- Understanding body language

- A lecture discussing scientific studies on how one's own body language influences oneself.