Blackstone's formulation

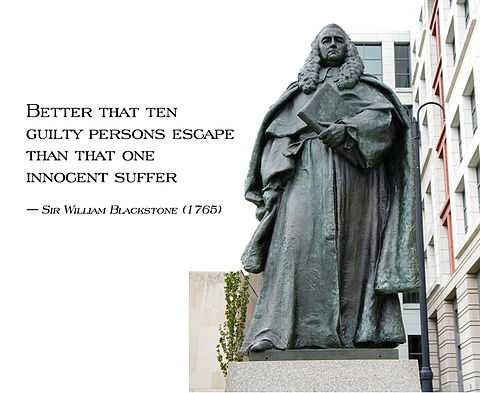

In criminal law, Blackstone's formulation (also known as Blackstone's ratio or the Blackstone ratio) is the principle that:

"It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer",

...as expressed by the English jurist William Blackstone in his seminal work, Commentaries on the Laws of England, published in the 1760s.

It is worthwhile to note that the actual numbers are not generally seen as important, so much as the idea that the State should not cause undue or mistaken harm "just in case". Historically, the details of the ratio change, but the message that government and the courts must err on the side of innocence is constant.

Historic expressions of the principle

The principle is much older than Blackstone's formulation, being closely tied to the presumption of innocence in criminal trials. An early example of the principle appears in the Bible (Genesis 18:23-32),[1][2] as:

Abraham drew near, and said, "Will you consume the righteous with the wicked? What if there are fifty righteous within the city? Will you consume and not spare the place for the fifty righteous who are in it?[ 1] ... What if ten are found there?" He [The Lord] said, "I will not destroy it for the ten's sake."[ 1]

The 12th-century legal theorist Maimonides, expounding on this passage as well as Exodus 23:7 ("the innocent and righteous slay thou not") argued that executing an accused criminal on anything less than absolute certainty would progressively lead to convictions merely "according to the judge's caprice. Hence the Exalted One has shut this door" against the use of presumptive evidence, for "it is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent one to death."[1][3][4]

Sir John Fortescue's De Laudibus Legum Angliae (c. 1470) states that "one would much rather that twenty guilty persons should escape the punishment of death, than that one innocent person should be condemned and suffer capitally."

Similarly, on 3 October 1692, while decrying the Salem witch trials, Increase Mather adapted Fortescue's statement and wrote, "It were better that Ten Suspected Witches should escape, than that one Innocent Person should be Condemned."[5]

Blackstone's Commentaries

While compiling his highly influential set of books on English common law, William Blackstone expressed the famous ratio this way:

| “ | All presumptive evidence of felony should be admitted cautiously; for the law holds it better that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent party suffer.[6] | ” |

This variation was absorbed by the British legal system, becoming a maxim by the early 19th century.[7] It was also absorbed into American common law, cited repeatedly by that country's Founding Fathers, later becoming a standard drilled into law students all the way into the 21st century.[8]

Defending British soldiers charged with murder for their role in the Boston Massacre, John Adams also expanded upon the rationale behind Blackstone's Formulation when he stated:

| “ | It is more important that innocence should be protected, than it is, that guilt be punished; for guilt and crimes are so frequent in this world, that all of them cannot be punished.... when innocence itself, is brought to the bar and condemned, especially to die, the subject will exclaim, 'it is immaterial to me whether I behave well or ill, for virtue itself is no security.' And if such a sentiment as this were to take hold in the mind of the subject that would be the end of all security whatsoever | ” |

Alternative viewpoints

More authoritarian personalities are supposed to have taken the opposite view; Bismarck is believed to have stated that "it is better that ten innocent men suffer than one guilty man escape;"[1] and Pol Pot[10] made similar remarks. Wolfgang Schäuble[11] referenced this principle while saying that it is not applicable to the context of preventing terrorist attacks.

Alexander Volokh cites an apparent questioning of the principle, with the tale of a Chinese professor who responds, "Better for whom?"[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "n Guilty Men", 146 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 173, Alexander Volokh, 1997.

- ↑ Why Terrorism Works: Understanding the Threat, Responding to the Challenge, Yale University Press, Alan M. Dershowitz, 2003

- ↑ Moses Maimonides, The Commandments, Neg. Comm. 290, at 269-271 (Charles B. Chavel trans., 1967).

- ↑ Goldstein, Warren (2006). Defending the human spirit: Jewish law's vision for a moral society. Feldheim Publishers. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-58330-732-8. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ↑ "Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits" 1693, p. 66 http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/speccol/mather/mather.html

- ↑ Commentaries on the laws of Engliand

- ↑ Re Hobson, 1 Lew. C. C. 261, 168 Eng. Rep. 1034 (1831) (Holroyd, J.).

- ↑ G. Tim Aynesworth, An illogical truism, Austin Am.-Statesman, April 18, 1996, at A14. Specifically, it is "drilled into [first year law students'] head[s] over and over again." Hurley Green, Sr., Shifting Scenes, Chi. Independent Bull., January 2, 1997, at 4.

- ↑ 9 Benjamin Franklin, Works 293 (1970), Letter from Benjamin Franklin to Benjamin Vaughan (14 March 1785)

- ↑ Locard, Henri. Pol Pot's Little Red Book: The Sayings of Angkar. Silkworm Books, 2004. pp. 209.

- ↑ "Schäuble: Zur Not auch gegen Unschuldige vorgehen". FAZ.

External links

- n Guilty Men, Alexander Volokh