Blackmail (1929 film)

| Blackmail | |

|---|---|

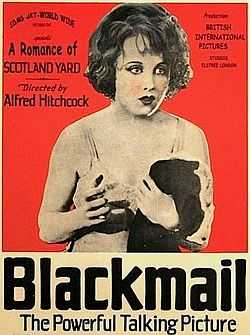

theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Produced by | John Maxwell |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

Blackmail (play) by Charles Bennett |

| Starring | |

| Music by |

Jimmy Campbell and Reg Connelly Billy Mayerl (song: "Miss Up-to-Date") |

| Cinematography | Jack E. Cox |

| Editing by | Emile de Ruelle |

| Distributed by |

|

| Release dates |

|

| Running time |

84 minutes (6740 ft silent, 7136 ft sound) |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

Blackmail is a 1929 British thriller drama film directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Anny Ondra, John Longden, and Cyril Ritchard. Based on the play Blackmail by Charles Bennett, the film is about a London woman who kills a man when he tries to rape her.

After starting production as a silent film, British International Pictures decided to convert Blackmail into a sound film during filming. A silent version was released for theaters not equipped for sound (at 6740 feet), with the sound version (7136 feet) released at the same time.[2] The silent version still exists in the British Film Institute collection.[3]

Plot

Scotland Yard Detective Frank Webber (John Longden) escorts his girlfriend Alice White (Anny Ondra) to a tea house. They have an argument and Frank storms out. While reconsidering his action, he sees Alice leave with Mr. Crewe (Cyril Ritchard), a painter she had earlier agreed to meet.

Crewe persuades a reluctant Alice into coming up to see his artists studio. She admires a painting of a laughing clown, and uses his palette and brushes to paint a cartoonish drawing of a face; he adds a few strokes of a feminine figure, and they both sign the "work". He gives her a dancer's outfit and Crewe sings and plays "Miss Up-to-Date" on the piano.

Crewe steals a kiss, to Alice's disgust, but as she is undressing and preparing to leave, he takes her dress from the changing area. He attempts to rape her, even though the police on the street below do not hear her cries for help. In desperation, Alice grabs a nearby bread knife and kills him. She angrily punches a hole in the painting of the clown, then leaves after attempting to remove any evidence of her presence in the flat, but forgets to take her gloves. She walks the streets of London all night in a daze.

When the body is found, the killing is assumed to be murder. Frank is assigned to the case and finds one of Alice's gloves. He recognizes both the glove and the dead man, but conceals this from his superior. Taking the glove, he goes to speak with Alice at her father's tobacco shop, but she is still too distraught to speak.

But as they hide from her father in a telephone booth, Tracy (Donald Calthrop), the model for the clown, arrives. He had seen Alice go up to Crewe's flat, and gone in and taken one of the gloves. When he sees Frank with the other one, he attempts to blackmail the couple. His first demands are petty ones and they accede. Then Frank learns by phone that Tracy is wanted for questioning: he was seen near the scene and has a criminal record. Frank sends for policemen and tells Tracy he will pay for the murder.

Alice is squeamish about Tracy being prosecuted for what she did, but still does not speak up. The tension mounts. When the police arrive, Tracy's nerve finally breaks and he flees. The chase leads to the British Museum, where he clambers onto the domed roof of the Reading Room, but slips, crashes through a skylight, and falls to his death inside. The police assume he was guilty of murder.

Unaware of this, Alice finally feels compelled to give herself up and goes to New Scotland Yard. She writes a confession letter and goes to see the Chief Inspector. Before she can bring herself to confess, the inspector receives a telephone call and asks Frank to deal with Alice. She finally tells him the truth -- that it was self-defense against an attack she cannot bear to speak of -- and they leave together. As they do, a policeman walks past, carrying the damaged painting of the laughing clown and the canvas where Alice has painted over her name and Crewe's.

Cast

|

|

Production

The film began production as a silent film. To cash in on the new popularity of talkies, the film's producer, John Maxwell of British International Pictures, gave Hitchcock the go-ahead to film a portion of the movie in sound. Hitchcock thought the idea absurd and surreptitiously filmed almost the entire feature in sound (the opening 6½ minutes of the sound version are silent, with musical accompaniment, as are some shorter scenes later), along with a silent version for theatres not yet equipped for talking pictures.

Blackmail, marketed as one of Britain's earliest "all-talkie" feature films, was recorded in the RCA Photophone sound-on-film process. (The first U.S. all-talking film, Lights of New York, was released in July 1928 by Warner Brothers in their Vitaphone sound-on-disc process.) The film was shot at British and Dominions Imperial Studios soundstage in Borehamwood, the first purpose-built sound studio in Europe.[4]

Lead actress Anny Ondra was raised in Prague and had a heavy Czech accent that was felt unsuitable for the film. Sound was in its infancy at the time and it was impossible to post-dub Ondra's voice. Rather than replace her and re-shoot her portions of the film, actress Joan Barry was hired to actually speak the dialogue off-camera while Anny lip-synched them for the film. This makes Ondra's performance seem slightly awkward.

Ondra's career in the UK was hurt by sound. She returned to Germany and retired from films after making a few additional movies and marrying boxer Max Schmeling in 1933. However, an amusing test film has survived of Hitchcock "interviewing" Ondra, in which the director teases the actress and asks her some personal questions.

Hitchcock used several elements that would become Hitchcock "trademarks" including a beautiful blonde in peril and a famous landmark in the finale. Without informing the producers, Hitchcock used the Schüfftan process to film the scenes in the Reading Room of the British Museum since the light levels were too low for normal filming.

On this production, future directors Ronald Neame worked as a "clapper boy" operating the clapperboard and Michael Powell took still photographs.[5]

The film was a critical and commercial hit. The sound was praised as inventive. A completed silent version of Blackmail was released in 1929 shortly after the talkie version hit theaters. The silent version of Blackmail actually ran longer in theaters and proved more popular, largely because most theaters in Britain were not yet equipped for sound. Despite the popularity of the silent version, history best remembers the landmark talkie version of Blackmail. It is the version now generally available although some critics consider the silent version superior. Alfred Hitchcock filmed the silent version with Sam Livesey as the Chief Inspector and the sound version with Harvey Braban in the same role.

Hitchcock's cameo

Alfred Hitchcock's cameo, a signature occurrence in many of Hitchcock's films, shows him being bothered by a small boy as he reads a book on the London Underground. The small boy was Jacque Carter.[citation needed] This is probably the lengthiest of Hitchcock's cameo appearances in his film career, appearing from 10 min. 24 sec to 10 min. 44 sec. As the director became better-known to audiences, especially when he appeared as the host of his own television series, he dramatically shortened his on-screen appearances.

Role in UK film history

As an early "talkie", the film is frequently cited by film historians as a landmark film,[6] and is often cited as the first truly British "all-talkie" feature film.[7][8]

Earlier British sound films include:

- The Gentleman, a short film in the Phonofilm sound-on-film process, was an excerpt of Nine O'Clock Revue, directed by William J. Elliott, and released in the UK in June 1925;

- The part-talking The Clue of the New Pin, based on the novel by Edgar Wallace, and filmed in British Phototone, a sound-on-disc system using 12-inch discs;

- The Crimson Circle, a UK-German silent film, also based on a Wallace novel, dubbed after the fact with the Phonofilm sound-on-film process;

- Black Waters, a British all-talkie production shot in the US and released on 6 April 1929.[9]

In March 1929, Pin and Circle were trade-shown at the same screening for film exhibitors in London.

In a public poll, Blackmail was voted the best British movie of 1929. In the same national UK poll, the best films of their respective years were The Constant Nymph (1928), Rookery Nook (1930), The Middle Watch (1931), and Sunshine Susie (1932).[10]

References

Notes

- ↑ Spoto (1984), pp. 131–32, 136.

- ↑ SilentEra entry

- ↑ BFI Database entry

- ↑ Tomlinson, Richard. "Borehamwood Film Studios: The British Hollywood". Herts Memories. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ BFI Database entry

- ↑ Rob White, Edward Buscombe British Film Institute film classics, Volume 1 Taylor & Francis, 2003

- ↑ Richard Allen, S. Ishii-Gonzalès Hitchcock: past and future Routledge, 2004

- ↑ St. Pierre, Paul Matthew Music hall mimesis in British film, 1895-1960: on the halls on the screen p.79. Associated University Presse, 2009

- ↑ Black Waters at IMDB

- ↑ ""SUNSHINE SUSIE".". The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 - 1950) (Perth, WA: National Library of Australia). 19 August 1933. p. 19 Edition: HOME EDITION. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

Bibliography

- Ryall, Tom, Blackmail (London: British Film Institute, 1993)

External links

- Blackmail at the Internet Movie Database

- Blackmail at Rotten Tomatoes

- Blackmail at the TCM Movie Database

- Blackmail at SilentEra

- Blackmail at BFI Database

- Blackmail at allmovie

- Blackmail at the British Film Institute's Screenonline

- Blackmail at Eyegate Gallery

- Blackmail Sound Test at YouTube

- Copyright Catalog at Library of Congress; select "Document number" and type "V8003P432"