Black hole electron

In physics, there is a speculative notion that if there were a black hole with the same mass and charge as an electron, it would share many of the properties of the electron including the magnetic moment and Compton wavelength. This idea is substantiated within a series of papers published by Albert Einstein between 1927 and 1949. In them, he showed that if elementary particles were treated as singularities in spacetime, it was unnecessary to postulate geodesic motion as part of general relativity.[1]

Problems

Quantum mechanics permits superluminal speeds for an object with as small a mass as the electron over distance scales larger than the Schwarzschild radius of the electron.[citation needed]

Schwarzschild radius

The Schwarzschild radius (rs) of any mass is calculated using the following formula:

For an electron,

- G is Newton's gravitational constant,

- m is the mass of the electron = 9.109×10−31 kg, and

- c is the speed of light.

This gives a value

- rs = 1.353×10−57 m.

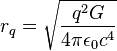

So if the electron has a radius as small as this, it would become a gravitational singularity. It would then have a number of properties in common with black holes. In the Reissner–Nordström metric, which describes electrically charged black holes, an analogous quantity rq is defined to be

where q is the charge and ε0 is the vacuum permittivity.

For an electron with q = −e = −1.602×10−19 C, this gives a value

- rq = 9.152×10−37 m.

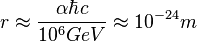

This value suggests that an electron black hole would be super-extremal and have a naked singularity. Standard quantum electrodynamics (QED) theory treats the electron as a point particle, a view completely supported by experiment. Practically, though, particle experiments cannot probe arbitrarily large energy scales, and so QED-based experiments bound the electron radius to a value smaller than the Compton wavelength of a large mass, on the order of 106 GeV, or

.

.

No proposed experiment would be capable of probing r to values as low as rs or rq, both of which are smaller than the Planck length. Super-extremal black holes are generally believed to be unstable. Furthermore, any physics smaller than the Planck length probably requires a consistent theory of quantum gravity.

See also

References

- ↑ Einstein, A.; Infeld, L.; Hoffmann, B. (January 1938). "The Gravitational Equations and the Problem of Motion". Annals of Mathematics. Second Series 39 (1): 65–100. doi:10.2307/1968714. JSTOR 1968714.

Further reading

- Burinskii, A. (2005). The Dirac–Kerr electron. arXiv:hep-th/0507109. Bibcode:2008GrCo...14..109B. doi:10.1134/S0202289308020011.

- Burinskii, A. (2007). Kerr Geometry as Space–Time Structure of the Dirac Electron. arXiv:0712.0577. Bibcode:2007arXiv0712.0577B.

- Duff, Michael (1994). Kaluza–Klein Theory in Perspective. arXiv:hep-th/9410046. Bibcode:1995okml.book...22D.

- Hawking, Stephen (1971). "Gravitationally collapsed objects of very low mass". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 152: 75. Bibcode:1971MNRAS.152...75H.

- Penrose, Roger (2004). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Salam, Abdus. "Impact of Quantum Gravity Theory on Particle Physics". In Isham, C. J.; Penrose, Roger; Sciama, Dennis William. Quantum Gravity: an Oxford Symposium. Oxford University Press.

- 't Hooft, Gerard (1990). "The black hole interpretation of string theory". Nuclear Physics B 335: 138–154. Bibcode:1990NuPhB.335..138T. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(90)90174-C.

- Murdzek, R. (2007). "The Geometry of the Torus Universe". International Journal of Modern Physics D 16 (4): 681–686. Bibcode:2007IJMPD..16..681M. doi:10.1142/S0218271807009826, which is related to "Hierarchical Cantor set in the large scale structure 3 with torus geometry".

Popular literature

- Brian Greene, The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions, and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory (1999), (See chapter 13)

- John A. Wheeler, Geons, Black Holes & Quantum Foam (1998), (See chapter 10)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||