Black War

| Black War of Tasmania | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Proclamation board labelled "Governor Davey's Proclamation" painted in Van Diemen's Land about 1830 in the time of Governor Arthur. Nailed to trees proclamation boards were designed to show that colonists and aboriginals were equal before the law, and depicted a policy of friendship and equal justice which did not exist at the height of the Black War.[1] |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Tasmanian Aborigines | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

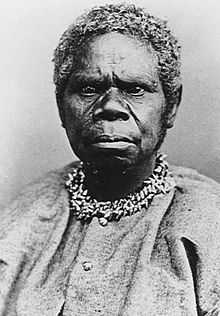

| Mangerner Truganini |

|||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| British colonists: over 1,000 soldiers and armed civilians[2] | Tasmanian Aborigines: about 1,000–2,000 in 1828[1] (including non-combatants) (there had been about 4,000 Aboriginals in Van Diemen's Land in 1803) |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 187[3] | Of the 1,000–2,000 full-blooded aboriginals in 1828 less than 250 survived by 1833. (See "Surrender and relocation" in this article) |

||||||||

The Black War refers to the period of conflict between British colonists and Tasmanian Aborigines in the early nineteenth century.[4][5] Although historians vary on their definition of when the conflict began and ended, it is best understood as the officially sanctioned time of declared martial law by the colonial government between 1828 and 1832.

The term Black War is also sometimes used to refer to other, later conflicts between European colonists and Aboriginal Australians on mainland Australia.[6]

Mass killings of Tasmanian Aborigines were reported as having occurred as part of the Black War in Van Diemen's Land.[7] The accuracy of some of these reports was questioned in the 1830s by the British Government's Commission of Inquiry, headed by Archdeacon (later Bishop) William Broughton and in the 20th century by historians, such as N. J. B. Plomley in the 1960s.[8] The controversy continued into the new millennium after historian Keith Windschuttle in 2002 questioned the accuracy of accounts of massacres and high fatalities,[9] arousing intense controversy in Australia.

In combination with epidemic impacts of introduced Eurasian infectious diseases, to which the Tasmanian Aborigines had no immunity, the conflict had such impact on the Tasmanian Aboriginal population that they were reported to have been exterminated.[4][5][10]

Small remnant groups' surviving the Black War were relocated to Bass Strait Islands. Their mixed European-Tasmanian descendants continue to live on the island today. Much of their languages, local ecological knowledge, and original cultures are now lost to Tasmania, perhaps with the exception of archaeological records plus historical records made at the time.[11]

Definition

The descriptions of the Black War differ, ranging from a series of small conflicts and massacres to assertions that the methods used during the conflicts constitute genocide. The Black War was one of many conflicts used as an example to define the term genocide as it began to be used in the 1940s.

The use of the term "war" is also sometimes disputed as no official war declaration was made, and only the colonists' side was fully equipped for war. Furthermore, some historians suggest terms such as civil war, occupation, murder or genocide would be more appropriate to describe what happened. Nonetheless, the name Black War has stuck, with the inclusion of the term "war" used loosely.

Details

As the Black War was never officially declared, historians vary in their dating of the extended conflict.

According to James Bonwick, the start of the Black War is 1804.[12] The first conflict between colonists and Aboriginals was on 3 May 1804. There were three surviving eyewitness accounts of what happened on that day. It is known that a large group of Aboriginals, possibly numbering 300 or more, came into the vicinity of the British settlement. The official report by Lt Moore, the commanding officer at the time, referred to an ‘attack’ by Aboriginals armed with spears and indicated that two Aboriginals were killed and an unknown number wounded.

Moore reported having fired a shot from a carronade (a small cannon) to ‘intimidate’ and disperse the Aboriginals but the report does not say whether it fired solid or canister shot or merely a blank charge meant to frighten. He reported no deaths from the cannon shot, however. The second account, also recorded shortly after the events, was contained in a letter written by the surgeon, Jacob Mountgarrett to Reverend Robert Knopwood. The letter referred to a ‘premeditated’ attack on the settlers in which three Aboriginals were killed. In addition to the cannon shot, 2 soldiers fired muskets in protection of a Risdon Cove settler being beaten on his farm by Aboriginals carrying waddies (clubs). These soldiers killed one Aboriginal outright, and mortally wounding another who was later found dead in a valley. It is therefore known that in the conflict some Aboriginals were killed, and that the colonists "had reason to suppose more were wounded, as one was seen to be taken away bleeding".

The conflict apparently arose when the Aboriginals discovered that some of the settlers had been hunting kangaroos. It is also known that an infant boy about 2–3 years old was left behind in what was viewed as a "retreat from a hostile attempt made upon the borders of the settlement". The last of the three accounts claimed that "There were a great many of the Natives slaughtered and wounded". This was according to Edward White, an Irish convict present on the scene of the events, speaking before a committee of inquiry in 1830, nearly 30 years later, but just how many he did not know. White, apparently the first to see the approaching Aboriginals, also said that "the natives did not threaten me; I was not afraid of them; (they) did not attack the soldiers; they would not have molested them; they had no spears with them; only waddies", though that they had no spears with them is questionable, and his claim needs some qualification. His contemporaries had believed the approach to be a potential attack by a group of Aboriginals that greatly outnumbered the colonists in the area, and spoke of "an attack the natives made", their "hostile Appearance", and "that their design was to attack us".

White also claimed that the bones of some of the Aboriginals were shipped to Sydney in two casks but this claim, like the others he made, is uncorroborated by any other eyewitness. Early Tasmanian history then went on to tell a story of hostilities between colonists and Aboriginals, and sporadic and retaliative guerrilla-tactic conflict by the Aboriginals in the early years of colonial settlement, usually over food resources, cruel treatment and killing of natives, and the abduction of aboriginal women and children as sexual partners and servants, escalating in the 1820s with the spread of pastoralism.[3][13][14][15][16]

Others date the conflict to 1826, when the Colonial Times newspaper published an announcement about self-defence reflecting the public mood of the colonists at the time. This was published at a time when relations between Aboriginals and settlers had almost reached the stage of open hostility, a result partly of the usurpation of the natives' hunting grounds, partly of the cruel treatment and killing of natives by shepherds, stockmen, bushrangers and sealers, and partly of the kidnapping of native children. The viewpoint of the settlers seemed to require either the extermination of the Aboriginals or their removal from lands that the settlers wanted to possess.[17]

Colonial Times 1826

On 1 December 1826, the Tasmanian Colonial Times declared that: "We make no pompous display of Philanthropy. We say this unequivocally SELF DEFENCE IS THE FIRST LAW OF NATURE. THE GOVERNMENT MUST REMOVE THE NATIVES—IF NOT, THEY WILL BE HUNTED DOWN LIKE WILD BEASTS, AND DESTROYED!" – Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser, 1826[18][19]

The Newspaper went on to argue that the only real solution would be to remove the Tasmanian Aboriginals and place them upon King's Island:

"...let them be compelled to grow potatoes, wheat, &c, catch seals and fish, and by degrees, they will lose their roving disposition and acquire some slight habits of industry, which is the first step of civilization."[18] [20]

However the article also pointed out that:

"If they are put upon the shores of New Holland they may be destroyed. If they remain here THEY ARE SURE TO BE DESTROYED. If they are sent to King's Island, they will be under restraint, but they will be free from committing or receiving violence and we are certainly bound by every principle of humanity to protect them as far as we can."[18] The editorial suggested that the relationship between settlers and Tasmanian Aboriginals had become violent and that the solution in their opinion, would be to place the aboriginals on one of the Bass Strait islands. The editorial also warned that until this occurred, violence would continue as settlers sought to defend themselves, resulting in more deaths.

Martial law declaration

Governor Arthur declared martial law in parts of Tasmania in November 1828 in a declaration beginning:

"Whereas the Black or Aboriginal Natives of this Island have for a considerable time past, carried on a series of indiscriminate attacks upon the persons and property of divers of His Majesty's subjects: and have especially of late perpetrated most cruel and sanguinary acts of violence and outrage; evincing an evident disposition systematically to kill and destroy the white inhabitants indiscriminately whenever an opportunity of doing so is presented."[21]

He ordered what were called "roving parties" to patrol the settled districts and capture Aboriginals there, authorising the patrols to shoot any Aboriginals who resisted. At the same time, Arthur instructed the military officers and magistrates in the area that the use of arms was to be a last resort.[22]

Conflict escalation

In February 1830, the government offered a bounty of £5 per adult and £2 per child, for Aboriginals captured alive.[23] On 20 August 1830, Governor Arthur's office issued a clarification that rewards were only for Aboriginals caught whilst engaged in aggression in the settled districts, and that settlers or convicts who went out and captured "inoffensive Natives in the remote of the remote and unsettled parts of the territory" would not receive a reward. Instead, "If, after the promulgation of this Notice, any wanton attack or aggression against the Natives becomes known to the Government, the offenders will be immediately brought to justice and punished."[24]

Black Line

During the same year, Governor Arthur called upon every able-bodied male colonist, convict or free, to form a human chain, later known as the Black Line, to perform a sweep of the area. As in game hunting, over 1000 soldiers and armed civilians[2] swept across the settled districts, moving south and east for several weeks, in an attempt to corral the Aboriginals on the Tasman Peninsula by closing off Eaglehawk Neck, the isthmus connecting the Tasman peninsula to the rest of the island. Arthur intended to have the Aboriginals live together on the peninsula where they could maintain their culture and language. The government and historians consider the Black Line to have been an excessively costly action. It was unsuccessful in capturing more than a few Aboriginals. Even though the tribes managed to avoid capture during these events, they were shaken by the size of the campaigns against them, and this brought them to a position whereby they were willing to surrender to George Augustus Robinson and move to Flinders Island.

Surrender and relocation

Largely through the efforts of George Augustus Robinson, known as "the Conciliator", by 1833 about 220 Tasmanian Aboriginals were persuaded to surrender with assurances that they would be protected and provided for by the government. By August 1834 the Aboriginal problem, as the colonists saw it, had been settled, since all but about a dozen natives had been removed from the mainland to the Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment on Flinders Island. Nonetheless, contact with introduced Eurasian diseases continued to reduce their numbers. By 1835 the Aboriginal population had shrunk to fewer than 150 natives, of whom about half were the survivors of those sent by Robinson to Flinders Island. In 1847, the last 47 living inhabitants of Wybalenna were transferred to Oyster Cove, south of Hobart, on the main island of Tasmania.

The last full-blooded tribal-born Palawa from the Oyster Cove community, a woman named Trugernanner (often rendered as Truganini), died in 1876 in Hobart. Her body was later exhumed and her skeleton given to Hobart’s Royal Society Museum which owned it for the next 98 years, placing it on display until in 1947 public sentiment caused the Museum to take her skeleton down and store it in the basement. In 1976, a century after her death, her skeleton was cremated and her ashes scattered by the descendants of her people. In 1997 the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, returned Trugernanner's necklace and bracelet to Tasmania. In 2002, some of her hair and skin were found in the collection of the Royal College of Surgeons of England and returned to Tasmania for burial.[25]

When Trugernanner died, the Tasmanian Government declared the island’s Aboriginals to be extinct. Its intention was to make everyone understand that the native problem was over, but the government was wrong on both counts. Other aboriginal women born from full-blooded tribal parents outlived her. For example, two indigenous women named Betty and Suke died towards the end of the nineteenth century on Kangaroo Island, off the coast of South Australia, where they had lived most of their lives in the forced company of sealers (though, living on Kangaroo Island, they were not "problems" to the Tasmanian authorities). Fanny Cochrane Smith, born on the Flinders Island aboriginal settlement, died in 1905 at Port Cygnet, Tasmania. Also the mixed-blood aboriginal community on the Furneaux group of islands continues to constitute a native community until the present day. Nonetheless, Truganini's passing was used to suggest the extinction of Tasmanian Aboriginals, and it was taught as fact in schools around the world, and for a long time, even in Tasmania, it was accepted as so.[26][27]

Charles Darwin's account

During the Beagle survey expedition, Charles Darwin visited Tasmania in February 1836 and noted in his diary that "The Aboriginal blacks are all removed & kept (in reality as prisoners) in a Promontory, the neck of which is guarded. I believe it was not possible to avoid this cruel step; although without doubt the misconduct of the Whites first led to the Necessity."[28] His Journal and Remarks published in 1839 (now known as The Voyage of the Beagle) noted that Hobart town, from the census of 1835, contained 13,826 inhabitants and the whole of Tasmania 36,505. He gave the following account of Tasmania's Black War:[29]

All the aboriginals have been removed to an island in Bass's Straits, so that Van Diemen's Land enjoys the great advantage of being free from a native population. This most cruel step seems to have been quite unavoidable, as the only means of stopping a fearful succession of robberies, burnings, and murders, committed by the blacks; but which sooner or later must have ended in their utter destruction. I fear there is no doubt that this train of evil and its consequences, originated in the infamous conduct of some of our countrymen. Thirty years is a short period, in which to have banished the last aboriginal from his native island,—and that island nearly as large as Ireland. I do not know a more striking instance of the comparative rate of increase of a civilized over a savage people.The correspondence to show the necessity of this step, which took place between the government at home and that of Van Diemen's Land, is very interesting: it is published in an appendix to Bischoff's History of Van Diemen's Land. Although numbers of natives were shot and taken prisoners in the skirmishing which was going on at intervals for several years; nothing seems fully to have impressed them with the idea of our overwhelming power, until the whole island, in 1830, was put under martial law, and by proclamation the whole population desired to assist in one great attempt to secure the entire race. The plan adopted was nearly similar to that of the great hunting-matches in India: a line reaching across the island was formed, with the intention of driving the natives into a cul-de-sac on Tasman's peninsula. The attempt failed; the natives, having tied up their dogs, stole during one night through the lines. This is far from surprising, when their practised senses, and accustomed manner of crawling after wild animals is considered. I have been assured that they can conceal themselves on almost bare ground, in a manner which until witnessed is scarcely credible. The country is every where scattered over with blackened stumps, and the dusky natives are easily mistaken for these objects. I have heard of a trial between a party of Englishmen and a native who stood in full view on the side of a bare hill. If the Englishmen closed their eyes for scarcely more than a second, he would squat down, and then they were never able to distinguish the man from the surrounding stumps. But to return to the hunting-match; the natives understanding this kind of warfare, were terribly alarmed, for they at once perceived the power and numbers of the whites. Shortly afterwards a party of thirteen belonging to two tribes came in; and, conscious of their unprotected condition, delivered themselves up in despair. Subsequently by the intrepid exertions of Mr Robinson, an active and benevolent man, who fearlessly visited by himself the most hostile of the natives, the whole were induced to act in a similar manner. They were then removed to Gun Carriage Island, where food and clothes were provided them. I fear from what I heard at Hobart Town, that they are very far from being contented: some even think the race will soon become extinct.

In the revised 1845 edition he quoted Paweł Edmund Strzelecki's Physical Description of New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land as stating that "at the epoch of their deportation in 1835, the number of natives amounted to 210. In 1842, that is after the interval of seven years, they mustered only fifty-four individuals; and, while each family of the interior of New South Wales, uncontaminated by contact with the whites, swarms with children, those of Flinders' Island had during eight years, an accession of only fourteen in number!"[30]

Ongoing historical disputes

The conflict has been a controversial area of study by historians, even characterised as among Australian history wars. Keith Windschuttle in his 2002 work, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803–1847,[31] questioned the historical evidence used to identify the number of Aborigines killed and the extent of conflict. He stated his belief that it had been exaggerated and challenged what is labelled the "Black armband view of history" of Tasmanian colonisation. His argument in turn has been challenged by a number of authors, for example see "Contra Windschuttle" by S.G. Foster in Quadrant, March 2003, 47:3.[32]

Literary references

H. G. Wells, in Chapter One of his novel The War of the Worlds, published in 1898, wrote:

- "We must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought, not only upon animals such as the vanished bison and dodo, but also upon its own inferior races. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years."[33]

This text from H. G. Wells was originally included as one of Microsoft's speech recognition engine training exercises for the user to read out loud into the microphone,[34] but the paragraph was deemed controversial for unspecified reasons and removed from a later version.

See also

- History wars

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- Tasmanian Aborigines

- Trugernanner & Fanny Cochrane Smith

- Manganinnie, an Australian 1980 film

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Governor Arthur's Proclamation". National Treasures. National Library of Australia.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Douglas, Sholto". Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Reviewing the History Wars". Stuart Macintyre.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bonwick, James (1870) The black war of Van Diemen's Land London : S. Low, Son & Marston.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Turnbull, Clive (1948) Black war : the extermination of the Tasmanian Aborigines. Melbourne : Cheshire

- ↑ Dewar, Michelle (1992) The 'Black War' in Arnhem Land : missionaries and the Yolngu 1908–1940, Darwin : Australian National University, North Australia Research Unit

- ↑ Ryan, L (2007) "Massacre in Tasmania? How Can We Know?" Accessed 15 August 2009

- ↑ Plomley, N.J.B., Friendly Mission

- ↑ Windschuttle, Keith (2002). The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803–1847, pp. 146–149

- ↑ Flood, Dr Josephine, The Original Australians, pp. 128–132. ISBN 978-1741148725.

- ↑ "Tasmanian Aboriginal Historical Services". Lia Pootah Community.

- ↑ "THE LAST TASMANIAN.". The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860–1954) (Hobart, Tas.: National Library of Australia). 17 February 1870. p. 2. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803–1847, Keith Windschuttle, 2002, ISBN 1-876492-05-8, pp16-26

- ↑ W.F.Refshauge (2007). "An analytical approach to the events at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, June 2007.

- ↑ http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/626394

- ↑ Phillip Tardif (6 April 2003). "So who's fabricating the history of Aboriginals?". Melbourne: The Age, 6 April 2003.

- ↑ "Robinson, George Augustus". Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Colonial Times.". Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser (Hobart, Tas. : 1825–1827) (Hobart, Tas.: National Library of Australia). 1 December 1826. p. 2. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ Henry Reynolds, 'Genocide in Tasmania,' in A. Dirk Moses (ed.), Genocide and Settler Society: Frontier Violence and Stolen Indigenous Indigenous Children in Australian History, Berghahn Books, pp. 127–149 p.142.

- ↑ Jane Lydon, Fantastic Dreaming: The Archaeology of an Aboriginal Mission, AltaMira Press, 2009 p.37. ISBN 978-0759111059.

- ↑ http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/4219798

- ↑ The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803–1847, Keith Windschuttle, 2002, ISBN 1-876492-05-8, pp. 170–171

- ↑ The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Windschuttle, p209

- ↑ The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Windschuttle, pp. 170–171

- ↑ Barkham, P. and Finlayson, A. (2002-05-31). "Museum returns sacred samples". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2006-07-11.

- ↑ "Truganini's Funeral", Onsman, Andrys

- ↑ "Telling the story of the Aboriginal Tasmanians of Kangaroo Island", Taylor, Rebe

- ↑ Keynes, R. D. ed. 2001. Charles Darwin's Beagle diary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press p. 408

- ↑ Darwin, C. R. 1839. Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their examination of the southern shores of South America, and the Beagle's circumnavigation of the globe. Journal and remarks. 1832–1836. London: Henry Colburn pp. 533–534

- ↑ Darwin, C. R. 1845. Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world, under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N. 2d edition. London: John Murray, p. 448

- ↑ The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803–1847, Keith Windschuttle, 2002, ISBN 1-876492-05-8

- ↑ "Contra Windschuttle", S.G. Foster Quadrant, March 2003, 47:3

- ↑

- ↑ http://usefulsounds.com/Useful_Sounds_No_048_Web_site_change_and_my_experience_with_MS_Speech_API_for_dictation-350

External links

- Extract from James Bonwick, Black War of Van Diemen’s Land, London, pp. 154–155 Accessed 15 August 2009

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||