Bivector (complex)

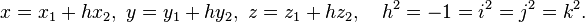

In mathematics, a bivector is the vector part of a biquaternion. For biquaternion q = w + x i + y j + zk, w is called the biscalar and xi + yj + zk is its bivector part. The coordinates w, x, y, z are complex numbers with imaginary unit h:

A bivector may be written as the sum of real and imaginary parts:

where  are vectors.

Thus the bivector

are vectors.

Thus the bivector

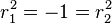

The Lie algebra of the Lorentz group is expressed by bivectors. In particular, if r1 and r2 are right versors so that  , then the biquaternion curve {exp θ r1 : θ ∈ R} traces over and over the unit circle in the plane {x + y r1 : x,y ∈ R}. Such a circle corresponds to the space rotation parameters of the Lorentz group.

, then the biquaternion curve {exp θ r1 : θ ∈ R} traces over and over the unit circle in the plane {x + y r1 : x,y ∈ R}. Such a circle corresponds to the space rotation parameters of the Lorentz group.

Now (h r2)2 = (−1)(−1) = +1, and the biquaternion curve {exp(θ(hr2)) : θ ∈ R} is a unit hyperbola in the plane {x + y r2 : x,y ∈ R}. The spacetime transformations in the Lorentz group that lead to Fitzgerald contractions and time dilation depend on a hyperbolic angle parameter. In the words of Ronald Shaw, "Bivectors are logarithms of Lorentz transformations"[1]

The commutator product of this Lie algebra is just twice the cross product on R3, for instance, [i,j] = ij −ji = 2k which is twice i × j. As Shaw wrote in 1970:

- Now it is well known that the Lie algebra of the homogeneous Lorentz group can be considered to be that of bivectors under commutation. ... The Lie algebra of bivectors is essentially that of complex 3-vectors, with the Lie product being defined to be the familiar cross product in (complex) 3-dimensional space.[2]

William Rowan Hamilton coined the term bivector[3] as the vector part of a biquaternion in his Lectures on Quaternions (1853).

Given a bivector r = r1 + h r2, the ellipse for which r1 and r2 are a pair of conjugate semi-diameters is called the directional ellipse of the bivector r.[4]

In the standard linear representation of biquaternions as 2 x 2 complex matrices acting on the complex plane with basis {1, h},

represents bivector q = v i + w j + x k.

represents bivector q = v i + w j + x k.

The conjugate transpose of this matrix corresponds to −q, so the representation of bivector q is a skew-Hermitian matrix.

Ludwik Silberstein studied a complexified electromagnetic field E + h B, where there are three components, each a complex number, known as the Riemann-Silberstein vector.

"Bivectors ... help describe elliptically polarized homogeneous and inhomogeneous plane waves — one vector for direction of propagation, one for amplitude"[5]

References

- ↑ Ronald Shaw and Graham Bowtell (1969) "The Bivector Logarithm of a Lorentz Transformation", Quarterly Journal of Mathematics 20:497–503

- ↑ Ronald Shaw (1970) "The subgroup structure of the homogeneous Lorentz group", Quarterly Journal of Mathematics 21:101–24

- ↑ Hamilton 1853 page 665

- ↑ EB Wilson 1901 page 436

- ↑ Telegraphic review of Bivectors and Waves in Mechanics and Optics, American Mathematical Monthly 1995 page 571

- Ph. Boulanger & M. Hayes (1993) Bivectors and Waves in Mechanics and Optics, Chapman and Hall.

- William Rowan Hamilton, (1853) Lectures on Quaternions, Royal Irish Academy, link from Cornell University Historical Mathematics Collection.

- William Edwin Hamilton (editor) (1866) Elements of Quaternions, page 219, University of Dublin Press, link from Google books.

- L. Silberstein (1907) "Electromagnetische Grundgleichungen in bivectorielle Behandlung", Annalen der Physik 22:579–86 & 24:783–4.

- Edwin Bidwell Wilson (1901) Vector Analysis, page 429