Biomedical engineering

Biomedical engineering (BME) is the application of engineering principles and design concepts to medicine and biology for healthcare purposes (e.g. diagnostic or therapeutic). This field seeks to close the gap between engineering and medicine: It combines the design and problem solving skills of engineering with medical and biological sciences to advance healthcare treatment, including diagnosis, monitoring, and therapy.[1]

Biomedical engineering has only recently emerged as its own study, compared to many other engineering fields. Such an evolution is common as a new field transitions from being an interdisciplinary specialization among already-established fields, to being considered a field in itself. Much of the work in biomedical engineering consists of research and development, spanning a broad array of subfields (see below). Prominent biomedical engineering applications include the development of biocompatible prostheses, various diagnostic and therapeutic medical devices ranging from clinical equipment to micro-implants, common imaging equipment such as MRIs and EEGs, regenerative tissue growth, pharmaceutical drugs and therapeutic biologicals.

Classification

Subdisciplines of biomedical engineering can be viewed from two angles, from the medical applications side and from the engineering side. A biomedical engineer must have some view of both sides. As with many medical specialties (e.g. cardiology, neurology), some BME sub-disciplines are identified by their associations with particular systems of the human body, such as:

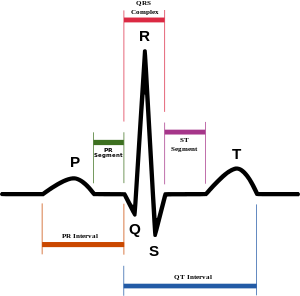

- Cardiovascular technology - which includes all drugs, biologics, and devices related with diagnostics and therapeutics of cardiovascular systems

- Neural technology - which includes all drugs, biologics, and devices related with diagnostics and therapeutics of the brain and nervous systems

- Orthopaedic technology - which includes all drugs, biologics, and devices related with diagnostics and therapeutics of skeletal systems

Those examples focus on particular aspects of anatomy or physiology. A variant on this approach is to identify types of technologies based on a kind of pathophysiology sought to remedy apart from any particular system of the body, for example:

- Cancer technology - which includes all drugs, biologics, and devices related with diagnostics and therapeutics of cancer

But more often, sub-disciplines within BME are classified by their association(s) with other more established engineering fields, which can include (at a broad level):

- Biochemical-BME, based on Chemical engineering - often associated with biochemical, cellular, molecular and tissue engineering, biomaterials, and biotransport.

- Bioelectrical-BME, based on Electrical engineering and Computer Science - often associated with bioelectrical and neural engineering, bioinstrumentation, biomedical imaging, and medical devices. This also tends to encompass optics and optical engineering - biomedical optics, bioinformatics, imaging and related medical devices.

- Biomechanical-BME, based on Mechanical engineering - often associated with biomechanics, biotransport, medical devices, and modeling of biological systems, like soft tissue mechanics.

One more way to sub-classify the discipline is on the basis of the products created. The therapeutic and diagnostic products used in healthcare generally fall under the following categories:

- Biologics and Biopharmaceuticals, often designed using the principles of synthetic biology (synthetic biology is an extension of genetic engineering). The design of biologic and biopharma products comes broadly under the BME-related (and overlapping) disciplines of biotechnology and bioengineering. Note that "biotechnology" can be a somewhat ambiguous term, sometimes loosely used interchangeably with BME in general; however, it more typically denotes specific products which use "biological systems, living organisms, or derivatives thereof." [2] Even some complex "medical devices" (see below) can reasonably be deemed "biotechnology" depending on the degree to which such elements are central to their principle of operation.

- Pharmaceutical Drugs (so-called "small-molecule" or non-biologic), which are commonly designed using the principles of synthetic chemistry and traditionally discovered using high-throughput screening methods at the beginning of the development process. Pharmaceuticals are related to biotechnology in two indirect ways: 1) certain major types (e.g. biologics) fall under both categories, and 2) together they essentially comprise the "non-medical-device" set of BME applications. (The "Device - Bio/Chemical" spectrum is an imperfect dichotomy, but one regulators often use, at least as a starting point.)

- Devices, which commonly employ mechanical and/or electrical aspects in conjunction with chemical and/or biological processing or analysis. They can range from microscopic or bench-top, and be either in vitro or in vivo. In the US, the FDA deems any medical product that is not a drug or a biologic to be a "device" by default (see "Regulation" section). Software with a medical purpose is also regarded as a device, whether stand-alone or as part of another device.

- Combination Products (not to be confused with fixed-dose combination drug products or FDCs), which involve more than one of the above categories in an integrated product (for example, a microchip implant for targeted drug delivery).

Tissue engineering

Tissue engineering, like genetic engineering (see below), is a major segment of Biotechnology - which overlaps significantly with BME.

One of the goals of tissue engineering is to create artificial organs (via biological material) for patients that need organ transplants. Biomedical engineers are currently researching methods of creating such organs. Researchers have grown solid jawbones[3] and tracheas from human stem cells towards this end. Several artificial urinary bladders actually have been grown in laboratories and transplanted successfully into human patients.[4] Bioartificial organs, which use both synthetic and biological components, are also a focus area in research, such as with hepatic assist devices that use liver cells within an artificial bioreactor construct.[5]

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, recombinant DNA technology, genetic modification/manipulation (GM) and gene splicing are terms that apply to the direct manipulation of an organism's genes. Genetic engineering is different from traditional breeding, where the organism's genes are manipulated indirectly. Genetic engineering uses the techniques of molecular cloning and transformation to alter the structure and characteristics of genes directly. Genetic engineering techniques have found success in numerous applications. Some examples are in improving crop technology (not a medical application, but see Biological Systems Engineering), the manufacture of synthetic human insulin through the use of modified bacteria, the manufacture of erythropoietin in hamster ovary cells, and the production of new types of experimental mice such as the oncomouse (cancer mouse) for research.

Neural engineering

Neural engineering (also known as Neuroengineering) is a discipline that uses engineering techniques to understand, repair, replace, or enhance neural systems. Neural engineers are uniquely qualified to solve design problems at the interface of living neural tissue and non-living constructs.

Pharmaceutical engineering

Pharmaceutical engineering is an interdisciplinary science that includes drug engineering, novel drug delivery and targeting, pharmaceutical technology, unit operations of Chemical Engineering, and Pharmaceutical Analysis. It may be deemed as a part of Pharmacy due to its focus on the use of technology on chemical agents in providing better medicinal treatment. The ISPE is an international body that certifies this now rapidly emerging interdisciplinary science.

Medical devices

This is an extremely broad category—essentially covering all health care products that do not achieve their intended results through predominantly chemical (e.g., pharmaceuticals) or biological (e.g., vaccines) means, and do not involve metabolism.

A medical device is intended for use in:

- the diagnosis of disease or other conditions, or

- in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease,

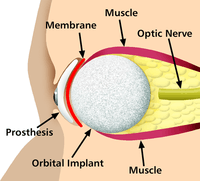

Some examples include pacemakers, infusion pumps, the heart-lung machine, dialysis machines, artificial organs, implants, artificial limbs, corrective lenses, cochlear implants, ocular prosthetics, facial prosthetics, somato prosthetics, and dental implants.

Stereolithography is a practical example of medical modeling being used to create physical objects. Beyond modeling organs and the human body, emerging engineering techniques are also currently used in the research and development of new devices for innovative therapies, treatments, patient monitoring, and early diagnosis of complex diseases.

Medical devices are regulated and classified (in the US) as follows (see also Regulation):

- Class I devices present minimal potential for harm to the user and are often simpler in design than Class II or Class III devices. Devices in this category include tongue depressors, bedpans, elastic bandages, examination gloves, and hand-held surgical instruments and other similar types of common equipment.

- Class II devices are subject to special controls in addition to the general controls of Class I devices. Special controls may include special labeling requirements, mandatory performance standards, and postmarket surveillance. Devices in this class are typically non-invasive and include x-ray machines, PACS, powered wheelchairs, infusion pumps, and surgical drapes.

- Class III devices generally require premarket approval (PMA) or premarket notification (510k), a scientific review to ensure the device's safety and effectiveness, in addition to the general controls of Class I. Examples include replacement heart valves, hip and knee joint implants, silicone gel-filled breast implants, implanted cerebellar stimulators, implantable pacemaker pulse generators and endosseous (intra-bone) implants.

Medical imaging

Medical/biomedical imaging is a major segment of medical devices. This area deals with enabling clinicians to directly or indirectly "view" things not visible in plain sight (such as due to their size, and/or location). This can involve utilizing ultrasound, magnetism, UV, other radiology, and other means.

- Fluoroscopy

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Nuclear medicine

- Positron emission tomography (PET) PET scansPET-CT scans

- Projection radiography such as X-rays and CT scans

- Tomography

- Ultrasound

- Optical microscopy

- Electron microscopy

Implants

An implant is a kind of medical device made to replace and act as a missing biological structure (as compared with a transplant, which indicates transplanted biomedical tissue). The surface of implants that contact the body might be made of a biomedical material such as titanium, silicone or apatite depending on what is the most functional. In some cases implants contain electronics e.g. artificial pacemaker and cochlear implants. Some implants are bioactive, such as subcutaneous drug delivery devices in the form of implantable pills or drug-eluting stents.

Bionics

Artificial body part replacement is just one of the things that bionics can do. Concerned with the intricate and thorough study of the properties and function of human body systems, bionics may be applied to solve some engineering problems. Careful study of the different function and processes of the eyes, ears, and other the way for improved cameras, television, radio transmitters and receivers, and many other useful tools. These developments have indeed made our lives better, but the best contribution that bionics has made is in the field of biomedical engineering. Biomedical Engineering is the building of useful replacements for various parts of the human body. Modern hospitals now have available spare parts to replace a part of the body that is badly damaged by injury or disease. Biomedical engineers who work hand in hand with doctors build these artificial body parts.

Clinical engineering

Clinical engineering is the branch of biomedical engineering dealing with the actual implementation of medical equipment and technologies in hospitals or other clinical settings. Major roles of clinical engineers include training and supervising biomedical equipment technicians (BMETs), selecting technological products/services and logistically managing their implementation, working with governmental regulators on inspections/audits, and serving as technological consultants for other hospital staff (e.g. physicians, administrators, I.T., etc.). Clinical engineers also advise and collaborate with medical device producers regarding prospective design improvements based on clinical experiences, as well as monitor the progression of the state of the art so as to redirect procurement patterns accordingly.

Their inherent focus on practical implementation of technology has tended to keep them oriented more towards incremental-level redesigns and reconfigurations, as opposed to revolutionary research & development or ideas that would be many years from clinical adoption; however, there is a growing effort to expand this time-horizon over which clinical engineers can influence the trajectory of biomedical innovation. In their various roles, they form a "bridge" between the primary designers and the end-users, by combining the perspectives of being both 1) close to the point-of-use, while 2) trained in product and process engineering. Clinical Engineering departments will sometimes hire not just biomedical engineers, but also industrial/systems engineers to help address operations research/optimization, human factors, cost analysis, etc. Also see safety engineering for a discussion of the procedures used to design safe systems.

Regulatory issues

Regulatory issues have been constantly increased in the last decades to respond to the many incidents caused by devices to patients. For example, from 2008 to 2011, in US, there were 119 FDA recalls of medical devices classified as class I. According to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Class I recall is associated to “a situation in which there is a reasonable probability that the use of, or exposure to, a product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death“ [6]

Regardless the country-specific legislation, the main regulatory objectives coincide worldwide.[7] For example, in the medical device regulations, a product must be:

1) Safe

and

2) Effective

3) For all the manufactured devices

A product is safe if patients, users and third parties do not run unacceptable risks of physical hazards (death, injuries, …) in its intended use. Protective measures have to be introduced on the devices to reduce residual risks at acceptable level if compared with the benefit derived from the use of it.

A product is effective if it performs as specified by the manufacturer in the intended use. Effectiveness is achieved through clinical evaluation, compliance to performance standards or demonstrations of substantial equivalence with an already marketed device.

The previous features have to be ensured for all the manufactured items of the medical device. This requires that a quality system shall be in place for all the relevant entities and processes that may impacts safety and effectiveness over the whole medical device lifecyle.

The medical device engineering area is among the most heavily regulated fields of engineering, and practicing biomedical engineers must routinely consult and cooperate with regulatory law attorneys and other experts. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the principal healthcare regulatory authority in the United States, having jurisdiction over medical devices, drugs, biologics, and combination products. The paramount objectives driving policy decisions by the FDA are safety and effectiveness of healthcare products that have to be assured through a quality system in place as specified under 21 CFR 829 regulation. In addition, because biomedical engineers often develop devices and technologies for "consumer" use, such as physical therapy devices (which are also "medical" devices), these may also be governed in some respects by the Consumer Product Safety Commission. The greatest hurdles tend to be 510K "clearance" (typically for Class 2 devices) or pre-market "approval" (typically for drugs and class 3 devices).

In the European context, safety effectiveness and quality is ensured through the "Conformity Assessment" that is defined as "the method by which a manufacturer demonstrates that its device complies with the requirements of the European Medical Device Directive". The directive specifies different procedures according to the class of the device ranging from the simple Declaration of Conformity (Annex VII) for Class I devices to EC verification (Annex IV), Production quality assurance (Annex V), Product quality assurance (Annex VI) and Full quality assurance (Annex II). The Medical Device Directive specifies detailed procedures for Certification. In general terms, these procedures include tests and verifications that are to be contained in specific deliveries such as the risk management file, the technical file and the quality system deliveries. The risk management file is the first deliverable that conditions the following design and manufacturing steps. Risk management stage shall drive the product so that product risks are reduced at an acceptable level with respect to the benefits expected for the patients for the use of the device. The technical file contains all the documentation data and records supporting medical device certification. FDA technical file has similar content although organized in different structure. The Quality System deliverables usually includes procedures that ensure quality throughout all product life cycle. The same standard (ISO EN 13485) is usually applied for quality management systems in US and worldwide.

In European Union, there are certifying entities named "Notified Bodies", accredited by European Member States. The Notified Bodies must ensure the effectiveness of the certification process for all medical devices apart from the class I devices where a declaration of conformity produced by the manufacturer is sufficient for marketing. Once a product has passed all the steps required by the Medical Device Directive, the device is entitled to bear a CE marking, indicating that the device is believed to be safe and effective when used as intended, and, therefore, it can be marketed within the European Union area.

The different regulatory arrangements sometimes result in particular technologies being developed first for either the U.S. or in Europe depending on the more favorable form of regulation. While nations often strive for substantive harmony to facilitate cross-national distribution, philosophical differences about the optimal extent of regulation can be a hindrance; more restrictive regulations seem appealing on an intuitive level, but critics decry the tradeoff cost in terms of slowing access to life-saving developments.

RoHS II

Directive 2011/65/EU, better known as RoHS 2 is a recast of legislation originally introduced in 2002. The original EU legislation “Restrictions of Certain Hazardous Substances in Electrical and Electronics Devices” (RoHS Directive 2002/95/EC) was replaced and superseded by 2011/65/EU published in July 2011 and commonly known as RoHS 2. RoHS seeks to limit the dangerous substances in circulation in electronics products, in particular toxins and heavy metals, which are subsequently released into the environment when such devices are recycled.

The scope of RoHS 2 is widened to include products previously excluded, such as medical devices and industrial equipment. In addition, manufacturers are now obliged to provide conformity risk assessments and test reports – or explain why they are lacking. For the first time, not only manufacturers, but also importers and distributors share a responsibility to ensure Electrical and Electronic Equipment within the scope of RoHS comply with the hazardous substances limits and have a CE mark on their products.

The Directive has to be transposed by the Member States by January 2, 2013.[8]

IEC 60601

The new International Standard IEC 60601 for home healthcare electro-medical devices defining the requirements for devices used in the home healthcare environment. IEC 60601-1-11 (2010) must now be incorporated into the design and verification of a wide range of home use and point of care medical devices along with other applicable standards in the IEC 60601 3rd edition series.

The mandatory date for implementation of the EN European version of the standard is June 1, 2013. The US FDA requires the use of the standard on June 30, 2013, while Health Canada recently extended the required date from June 2012 to April 2013. The North American agencies will only require these standards for new device submissions, while the EU will take the more severe approach of requiring all applicable devices being placed on the market to consider the home healthcare standard.

Training and certification

Education

Biomedical engineers require considerable knowledge of both engineering and biology, and typically have a Master's (M.S.,M.Tech, M.S.E., or M.Eng.) or a Doctoral (Ph.D.) degree in BME (Biomedical Engineering) or another branch of engineering with considerable potential for BME overlap. As interest in BME increases, many engineering colleges now have a Biomedical Engineering Department or Program, with offerings ranging from the undergraduate (B.Tech,B.S., B.Eng or B.S.E.) to doctoral levels. As noted above, biomedical engineering has only recently been emerging as its own discipline rather than a cross-disciplinary hybrid specialization of other disciplines; and BME programs at all levels are becoming more widespread, including the Bachelor of Science in Biomedical Engineering which actually includes so much biological science content that many students use it as a "pre-med" major in preparation for medical school. The number of biomedical engineers is expected to rise as both a cause and effect of improvements in medical technology.[9]

In the U.S., an increasing number of undergraduate programs are also becoming recognized by ABET as accredited bioengineering/biomedical engineering programs. Over 65 programs are currently accredited by ABET.[10][11]

In Canada and Australia, accredited graduate programs in Biomedical Engineering are common, for example in Universities such as McMaster University, and the first Canadian undergraduate BME program at Ryerson University offering a four-year B.Eng program.[12][13][14][15] The Polytechnique in Montreal is also offering a bachelors's degree in biomedical engineering.

As with many degrees, the reputation and ranking of a program may factor into the desirability of a degree holder for either employment or graduate admission. The reputation of many undergraduate degrees are also linked to the institution's graduate or research programs, which have some tangible factors for rating, such as research funding and volume, publications and citations. With BME specifically, the ranking of a university's hospital and medical school can also be a significant factor in the perceived prestige of its BME department/program.

Graduate education is a particularly important aspect in BME. While many engineering fields (such as mechanical or electrical engineering) do not need graduate-level training to obtain an entry-level job in their field, the majority of BME positions do prefer or even require them.[16] Since most BME-related professions involve scientific research, such as in pharmaceutical and medical device development, graduate education is almost a requirement (as undergraduate degrees typically do not involve sufficient research training and experience). This can be either a Masters or Doctoral level degree; while in certain specialties a Ph.D. is notably more common than in others, it is hardly ever the majority (except in academia). In fact, the perceived need for some kind of graduate credential is so strong that some undergraduate BME programs will actively discourage students from majoring in BME without an expressed intention to also obtain a masters degree or apply to medical school afterwards.

Graduate programs in BME, like in other scientific fields, are highly varied, and particular programs may emphasize certain aspects within the field. They may also feature extensive collaborative efforts with programs in other fields (such as the University's Medical School or other engineering divisions), owing again to the interdisciplinary nature of BME. M.S. and Ph.D. programs will typically require applicants to have an undergraduate degree in BME, or another engineering discipline (plus certain life science coursework), or life science (plus certain engineering coursework).

Education in BME also varies greatly around the world. By virtue of its extensive biotechnology sector, its numerous major universities, and relatively few internal barriers, the U.S. has progressed a great deal in its development of BME education and training opportunities. Europe, which also has a large biotechnology sector and an impressive education system, has encountered trouble in creating uniform standards as the European community attempts to supplant some of the national jurisdictional barriers that still exist. Recently, initiatives such as BIOMEDEA have sprung up to develop BME-related education and professional standards.[17] Other countries, such as Australia, are recognizing and moving to correct deficiencies in their BME education.[18] Also, as high technology endeavors are usually marks of developed nations, some areas of the world are prone to slower development in education, including in BME.

Licensure/certification

Engineering licensure in the US is largely optional, and rarely specified by branch/discipline. As with other learned professions, each state has certain (fairly similar) requirements for becoming licensed as a registered Professional Engineer (PE), but in practice such a license is not required to practice in the majority of situations (due to an exception known as the private industry exemption, which effectively applies to the vast majority of American engineers). This is notably not the case in many other countries, where a license is as legally necessary to practice engineering as it is for law or medicine.

Biomedical engineering is regulated in some countries, such as Australia, but registration is typically only recommended and not required.[19]

In the UK, mechanical engineers working in the areas of Medical Engineering, Bioengineering or Biomedical engineering can gain Chartered Engineer status through the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. The Institution also runs the Engineering in Medicine and Health Division.[20]

The Fundamentals of Engineering exam - the first (and more general) of two licensure examinations for most U.S. jurisdictions—does now cover biology (although technically not BME). For the second exam, called the Principles and Practices, Part 2, or the Professional Engineering exam, candidates may select a particular engineering discipline's content to be tested on; there is currently not an option for BME with this, meaning that any biomedical engineers seeking a license must prepare to take this examination in another category (which does not affect the actual license, since most jurisdictions do not recognize discipline specialties anyway). However, the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) is, as of 2009, exploring the possibility of seeking to implement a BME-specific version of this exam to facilitate biomedical engineers pursuing licensure.

Beyond governmental registration, certain private-sector professional/industrial organizations also offer certifications with varying degrees of prominence. One such example is the Certified Clinical Engineer (CCE) certification for Clinical engineers.

Founding figures

- Leslie Geddes (deceased)- Professor Emeritus at Purdue University, electrical engineer, inventor, and educator of over 2000 biomedical engineers, received a National Medal of Technology in 2006 from President George Bush[21] for his more than 50 years of contributions that have spawned innovations ranging from burn treatments to miniature defibrillators, ligament repair to tiny blood pressure monitors for premature infants, as well as a new method for performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

- Y. C. Fung - professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego, considered by many to be the founder of modern Biomechanics[22]

- Robert Langer - Institute Professor at MIT, runs the largest BME laboratory in the world, pioneer in drug delivery and tissue engineering[23]

- Herbert Lissner (deceased) - Professor of Engineering Mechanics at Wayne State University. Initiated studies on blunt head trauma and injury thresholds beginning in 1939 in collaboration with Dr. E.S. Gurdjian, a neurosurgeon at Wayne State's School of Medicine. Individual for whom the American Society of Mechanical Engineers' top award in Biomedical Engineering, the Herbert R. Lissner Medal, is named.

- Nicholas A. Peppas - Chaired Professor in Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, pioneer in drug delivery, biomaterials, hydrogels and nanobiotechnology.

- Otto Schmitt (deceased) - biophysicist with significant contributions to BME, working with biomimetics

- Ascher Shapiro (deceased) - Institute Professor at MIT, contributed to the development of the BME field, medical devices (e.g. intra-aortic balloons)

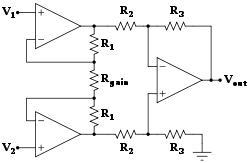

- John G. Webster - Professor Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, a pioneer in the field of instrumentation amplifiers for the recording of electrophysiological signals

- Robert Plonsey - Professor Emeritus at Duke University, pioneer of electrophysiology[24]

- U. A. Whitaker (deceased) - provider of The Whitaker Foundation, which supported research and education in BME by providing over $700 million to various universities, helping to create 30 BME programs and helping finance the construction of 13 buildings[25]

- Frederick Thurstone (deceased) - Professor Emeritus at Duke University, pioneer of diagnostic ultrasound[26]

- Kenneth R. Diller - Chaired and Endowed Professor in Engineering, University of Texas at Austin. Founded the BME department at UT Austin. Pioneer in bioheat transfer, mass transfer, and biotransport

- Alfred E. Mann - Physicist, entrepreneur and philanthropist. A pioneer in the field of Biomedical Engineering.[27]

- Forrest Bird - aviator and pioneer in the invention of mechanical ventilators

- Willem Johan Kolff (deceased) - pioneer of hemodialysis as well as in the field of artificial organs

- John James Rickard Macleod(deceased) - one of the co-discoverers of insulin at Case Western Reserve University.

See also

- Biomedicine

- Cardiophysics

- Medical biophysics

- Physiome

References

- ↑ Biomedical engineer prospects

- ↑ "Text of the Convention on Biological Diversity". Cbd.int. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ↑ "Jaw bone created from stem cells". October 10, 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ↑ "Doctors grow organs from patients' own cells". CNN. April 3, 2006.

- ↑ Trial begins for first artificial liver device using human cells, University of Chicago, February 25, 1999

- ↑ U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Medical & Radiation Emitting Device Recalls http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfres/res.cfm

- ↑ World Health Organization (WHO), 2003 Medical Device Regulations Global overview and guiding principles. http://www.who.int/medical_devices/publications/en/MD_Regulations.pdf (last visit Sept 2013)

- ↑ SGS, SafeGuardS Bulletin, Retrieved 08/20/2012

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics - Profile for Engineers

- ↑ "Accredited Biomedical Engineering Programs". Bmes.org. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ↑ ABET List of Accredited Engineering Programs

- ↑ "McMaster School of Biomedical Engineering". Msbe.mcmaster.ca. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ↑ "Biomedical Engineering - Electrical and Computer Eng. Ryerson". Ee.ryerson.ca. 2011-08-04. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ↑ "Ryerson Biomedical Engineering Students Invent Brain-Controlled Prosthetic Arm". STUDY Magazine. 2011-04-01. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ↑ "Biomedical Engineering". Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics - Job Outlook for Engineers

- ↑ BIOMEDEA

- ↑ Biomedical Engineering Curriculum: A Comparison Between the USA, Europe and Australia

- ↑ National Engineering Registration Board - Areas Of Practice - NPER Areas

- ↑

- ↑ "Leslie Geddes - 2006 National Medal of Technology". YouTube. 2007-07-31. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ↑ YC “Bert” Fung: The Father of Modern Biomechanics (pdf)

- ↑ Colleagues honor Langer for 30 years of innovation, MIT News Office

- ↑ "Faculty - Duke BME". Fds.duke.edu. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ↑ "The Whitaker Foundation". Whitaker.org. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ↑ "Biomedical Engineering Professor Emeritus Fredrick L. Thurstone Dies". Pratt.duke.edu. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ↑ Gallegos, Emma (2010-10-25). "Alfred E. Mann Foundation for Scientific Research (AMF)". Aemf.org. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

Further reading

- Bronzino, Joseph D. (April 2006). The Biomedical Engineering Handbook, Third Edition. [CRC Press]. ISBN 978-0-8493-2124-5.

- Villafane, Carlos, CBET. (June 2009). Biomed: From the Student's Perspective, First Edition. [Techniciansfriend.com]. ISBN 978-1-61539-663-4.

- Medical engineering stories in the news

External links

| At Wikiversity you can learn more and teach others about Biomedical engineering at: |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||