Biomaterial Surface Modifications

Biomaterials exhibit various degrees of compatibility with the harsh environment within a living organism. They need to un-reactive chemically and physically with the body, as well as integrate when with tissue.[1] The extent of compatibility varies based on the application and material required. Often modifications to the surface of a biomaterial system are required to maximize performance. The surface can be modified in many ways, including plasma modification and applying coatings to the substrate. Surface modifications can be used to affect surface energy, adhesion, biocompatibility, chemical inertness, lubricity, sterility, asepsis, thrombogenicity, susceptibility to corrosion, degradation, and hydrophilicity.

Background of Polymer Biomaterials

Polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon)

Teflon is a hydrophobic polymer composed of a carbon chain saturated with fluorine atoms. The fluorine-carbon bond is largely ionic producing a strong dipole. The dipole prevents Teflon from being susceptible to Van der Waals forces, so other materials will not stick to the surface.[2] Teflon is commonly used to reduce friction in biomaterial applications such as in arterial grafts, catheters, and guide wire coatings.

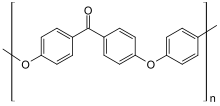

Polyetheretherketone (PEEK)

PEEK is a semicrystalline polymer composed of benzene, ketone, and ether groups. PEEK is known for having good physical properties including high wear resistance and low moisture absorption [2] and has been used for biomedical implants due to its relative inertness inside of the human body.

Plasma modification of biomaterials

Plasma modification is one way to alter the surface of biomaterials to enhance their properties. During plasma modification techniques, the surface is subjected to high levels of excited gases that alter the surface of the material. Plasma's are generally generated with a radio frequency (RF) field. Additional methods include applying a large (~1KV) DC voltage across electrodes engulfed in a gas. The plasma is then used to expose the biomaterial surface, which can break or form chemical bonds. This is the result of physical collisions or chemical reactions of the excited gas molecules with the surface. This changes the surface chemistry and therefore surface energy of the material which affects the adhesion, biocompatibility, chemical inertness, lubricity, and sterilization of the material. The table below shows several biomaterial applications of plasma treatments.[3]

| Applications of Plasma Treatments | Devices | Materials | Purposes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biosensor | Sensor Membranes, Diagnostic biosensors | PC, Cellulose,Cuprophane, PP, PS | Immobilization of biomolecules, non-fouling surfaces |

| Cardiovascular | Vascular grafts, Catheters | PET,PTFE,PE,SiR | Improved biocompatibility, Wettability tailoring, lubricious coatings, Reduced friction, Antimicrobial coatings |

| Dental | Dental Implants | Ti alloys | Enhanced Cell growth |

| Orthopedic | Joints,Ligaments | UHMWPE,PET | Enhance bone adhesion, Enhanced tissue in-growth |

| Others | General uses | Example | Sterilization, Surface cleaning, Etching, Adhesion promotion, Lubricity tailoring |

Surface Energy

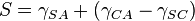

The surface energy is equal to the sum of disrupted molecular bonds that occur at the interface between two different phases. Surface energy can be estimated by contact angle measurements using a version of the Young–Laplace equation:

Where  is the surface tension at the interface of solid and vapor,

is the surface tension at the interface of solid and vapor,  is the surface tension at the interface of solid and liquid, and

is the surface tension at the interface of solid and liquid, and  is the surface tension at the interface of liquid and vapor. Plasma modification techniques alter the surface of the material, and subsequently the surface energy. Changes in surface energy then alter the surface properties of the material.

is the surface tension at the interface of liquid and vapor. Plasma modification techniques alter the surface of the material, and subsequently the surface energy. Changes in surface energy then alter the surface properties of the material.

Surface Functionalization

Surface modification techniques have been extensively researched for the application of adsorbing biological molecules. Surface functionalization can be performed by exposing surfaces to RF plasma. Many gases can be excited and used to functionalize surfaces for a wide variety of applications. Common techniques include using air plasma, oxygen plasma, and ammonia plasma as well as other exotic gases. Each gas can have varying effects on a substrate. These effects decay with time as reactions with molecules in air and contamination occur.

Plasma Treatment to Reduce Thrombogenesis

Ammonia plasma treatment can be used to attach amine functional groups. These functional groups lock on to anticoagulants like Heparin decreasing thrombogenicity.[5]

Covalent Immobilization by Gas Plasma RF Glow Discharge

Polysaccharides have been used as thin film coatings for biomaterial surfaces. Polysaccharides are extremely hydrophilic and will have small contact angles. They can be used for a wide range of applications due to their wide range of compositions. They can be used to reduce the adsorption of proteins to biomaterial surfaces. Additionally, they can be used as receptor sites, targeting specific biomolecules. This can be used to activate specific biological responses.

Covalent attachment to a substrate is necessary to immobilize polysaccharides, otherwise they will rapidly desorb in a biological environment. This can be a challenge due to the fact that the majority of biomaterials do not possess the surface properties to covalently attach polysaccharides. This can be achieved by the introduction of amine groups by RF glow discharge plasma. Gases used to form amine groups, including ammonia or n-heptylamine vapor, can be used to deposit a thin film coating containing surface amines. Polysaccharides must also be activated by oxidation of anhydroglucopyranoside subunits. This can be completed with sodium metaperiodate (NaIO4). This reaction converts anhydroglucopyranoside subunits to cyclic hemiacetal structures, which can be reacted with amine groups to form a Schiff base linkage (a carbon-nitrogen double bond). These linkages are unstable and will easily dissociate. Sodium cyanoborohydride (NaBH3CN) can be used as a stabilizer by reducing the linkages back to an amine.[6]

Surface Cleaning

There are many examples of contamination of biomaterials that are specific to the preparation or manufacturing process. Additionally, nearly all surfaces are prone to contamination of organic impurities in the air. Contamination layers are usually limited to a monolayer or less of atoms and are thus only detectable by surface analysis techniques, such as XPS. It is unknown whether this sort of contamination is harmful, yet it is still regarded as contamination and will most certainly have an impact on surface properties.

Glow discharge plasma treatment is a technique that is used for cleaning contamination from biomaterial surfaces. Plasma treatment has been used for various biological evaluation studies to increase the surface energy of biomaterial surfaces, as well as cleaning. Plasma treatment has also been proposed for sterilization of biomaterials for potential implants.[7]

Modification of Biomaterials with Polymer Coatings

Another method of altering surface properties of biomaterials is to coat the surface. Coatings are used in many applications to improve biocompatibility and alter properties such as adsorption, lubricity, thrombogenicity, degradation, and corrosion.

Adhesion of Coatings

In general, the lower the surface tension of a liquid coating, the easier it will be to form a satisfactory wet film from it. The difference between the surface tension of a coating and the surface energy of a solid substrate to which a coating is applied affects how the liquid coating flows out over the substrate. It also affects the strength of the adhesive bond between the substrate and the dry film. If for instance, the surface tension of the coating is higher than the surface tension of the substrate, then the coating will not spread out and form a film. As the surface tension of the substrate is increased, it will reach a point to where the coating will successfully wet the substrate but have poor adhesion. Continuous increase in the coating surface tension will result in better wetting in film formation and better dry film adhesion.[8]

More specifically whether a liquid coating will spread across a solid substrate can be determined from the surface energies of the involved materials by using the following equation:

Where S is the coefficient of spreading,  is the surface energy of the substrate in air,

is the surface energy of the substrate in air,  is the surface energy of the liquid coating in air and

is the surface energy of the liquid coating in air and  is the interfacial energy between the coating and the substrate. If S is positive the liquid will cover the surface and the coating will adhere well. If S is negative the coating will not completely cover the surface, producing poor adhesion.

is the interfacial energy between the coating and the substrate. If S is positive the liquid will cover the surface and the coating will adhere well. If S is negative the coating will not completely cover the surface, producing poor adhesion.

Corrosion Protection

Organic coatings are a common way to protect a metallic substrate from corrosion. Up until ~1950 it was thought that coatings act as a physical barrier which disallows moisture and oxygen to contact the metallic substrate and form a corrosion cell. This cannot be the case because the permeability of paint films is very high. It has since been discovered that corrosion protection of steel depends greatly upon the adhesion of an noncorrosive coating when in the presence of water. With low adhesion, osmotic cells form underneath the coating with high enough pressures to form blisters, which expose more unprotected steel. Additional non-osmotic mechanisms have also been proposed. In either case, sufficient adhesion to resist displacement forces is required for corrosion protection.[10]

Guide Wires

Guide wires are an example of an application for biomedical coatings. Guide wires are used in coronary angioplasty to correct the effects of coronary artery disease, a disease that allows plaque build up on the walls of the arteries. The guide wire is threaded up through the femoral artery to the obstruction. The guide wire guides the balloon catheter to the obstruction where the catheter is inflated to press the plaque against the arterial walls.[11] Guide wires are commonly made from stainless steel or Nitinol and require polymer coatings as a surface modification to reduce friction in the arteries. The coating of the guide wire can affect the trackability, or the ability of the wire to move through the artery without kinking, the tactile feel, or the ability of the doctor to feel the guide wire's movements, and the thrombogenicity of the wire.

Hydrophilic Coatings

Hydrophilic coatings can reduce friction in the arteries by up to 83% when compared to bare wires due to their high surface energy.[12] When the hydrophilic coatings come into contact with bodily fluids they form a waxy surface texture that allows the wire to slide easily through the arteries. Guide wires with hydrophilic coatings have increased trackability and are not very thrombogenic; however the low coefficient of friction increases the risk of the wire slipping and perforating the artery.[13]

Hydrophobic Coatings

Teflon and Silicone are commonly used hydrophobic coatings for coronary guide wires. Hydrophobic coatings have a lower surface energy and reduce friction in the arteries by up to 48%.[12] Hydrophobic coatings do not need to be in contact with fluids to form a slippery texture. Hydrophobic coatings maintain tactile sensation in the artery, allowing doctors full control of the wire at all times and reducing the risk of perforation; though, the coatings are more thrombogenic than hydrophilic coatings.[13] The thrombogenicity is due to the proteins in the blood adapting to the hydrophobic environment when they adhere to the coating. This causes an irreversible change for the protein, and the protein remains stuck to the coating allowing for a blood clot to form.[14]

Magnetic Resonance Compatible Guide Wires

Using an MRI to image the guide wire during use would have an advantage over using x-rays because the surrounding tissue can be examined while the guide wire is advanced. Because most guide wires' core materials are stainless steel they are not capable of being imaged with an MRI. Nitinol wires are not magnetic and could potentially be imaged, but in practice the conductive nitinol heats up under the magnetic radiation which would damage surrounding tissues. An alternative that is being examined is to replace contemporary guide wires with PEEK cores, coated with iron particle embedded synthetic polymers.[15]

| Material | Surface Energy (mN/m) |

|---|---|

| Teflon | 24 [9] |

| Silicone | 22 [16] |

| PEEK | 42.1 [17] |

| Stainless Steel | 44.5 [18] |

| Nitinol | 49 [19] |

References

- ↑ Amid, P. K.; Shulman, A. G.; Lichtenstein, I. L.; Hakakha, M. (1994). "Biomaterials for abdominal wall hernia surgery and principles of their applications". Langenbecks Archiv für Chirurgie 379 (3): 168–71. doi:10.1007/BF00680113.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mueller, Anja (2006). "Fluorinated Hyperbranched Polymers". Sigma Aldrich. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ↑ Loh, Ih-Houng. "Plasma Surface Modification In Biomedical Applications". AST Technical Journal.

- ↑ Zisman, W. A. (1964). "Relation of the Equilibrium Contact Angle to Liquid and Solid Constitution". In Fowkes, Frederick M. Contact Angle, Wettability, and Adhesion. Advances in Chemistry 43. pp. 1–51. doi:10.1021/ba-1964-0043.ch001. ISBN 0-8412-0044-0.

- ↑ Yuan, Shengmei; Szakalas-Gratzl, Gyongyi; Ziats, Nicholas P.; Jacobsen, Donald W.; Kottke-Marchant, Kandice; Marchant, Roger E. (1993). "Immobilization of high-affinity heparin oligosaccharides to radiofrequency plasma-modified polyethylene". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research 27 (6): 811–9. doi:10.1002/jbm.820270614. PMID 8408111.

- ↑ Dai, Liming; Stjohn, Heather A. W.; Bi, Jingjing; Zientek, Paul; Chatelier, Ronald C.; Griesser, Hans J. (2000). "Biomedical coatings by the covalent immobilization of polysaccharides onto gas-plasma-activated polymer surfaces". Surface and Interface Analysis 29: 46–55. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9918(200001)29:1<46::AID-SIA692>3.0.CO;2-6.

- ↑ Aronsson, B.-O.; Lausmaa, J.; Kasemo, B. (1997). "Glow discharge plasma treatment for surface cleaning and modification of metallic biomaterials". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research 35 (1): 49–73. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199704)35:1<49::AID-JBM6>3.0.CO;2-M. PMID 9104698.

- ↑ "Surface Tension, Surface Energy, Contact Angle and Adhesion". Paint Research Association. 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Van Iseghem, Lawrence. "Coating Plastics - Some Important Concepts from a Formulators Perspective". Van Technologies Inc. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ Z.W. Wicks; Frank N. Jones; S Peter Pappas; Douglas A. Wicks. Organic Coatings Science and Technology (2nd expanded ed.). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ↑ Gandelman, Glenn (March 22, 2013). "Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA)". Medline Plus. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Schröder, J (1993). "The mechanical properties of guidewires. Part III: Sliding friction". Cardiovascular and interventional radiology 16 (2): 93–7. doi:10.1007/BF02602986. PMID 8485751.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Erglis, Andrejs; Narbute, Inga; Sondore, Dace; Grave, Alona; Jegere, Sanda (2010). "Tools & Techniques: coronary guidewires". EuroIntervention 6 (1): 168–9. doi:10.4244/ (inactive June 16, 2013). PMID 20542813.

- ↑ Labarre, Denis (2001). "Improving blood compatibility of polymeric surfaces". Trends in Biomaterials and Artificial Organs 15 (1): 1–3.

- ↑ Mekle, Ralf; Hofmann, Eugen; Scheffler, Klaus; Bilecen, Deniz (2006). "A polymer-based MR-compatible guidewire: A study to explore new prospects for interventional peripheral magnetic resonance angiography (ipMRA)". Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 23 (2): 145–55. doi:10.1002/jmri.20486. PMID 16374877.

- ↑ Thanawala, Shilpa K.; Chaudhury, Manoj K. (2000). "Surface Modification of Silicone Elastomer Using Perfluorinated Ether". Langmuir 16 (3): 1256–60. doi:10.1021/la9906626.

- ↑ "Solid surface energy data (SFE) for common polymers". November 20, 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ "Selected literature values for surface free energy of solids". Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ Michiardi, Alexandra; Aparicio, Conrado; Ratner, Buddy D.; Planell, Josep A.; Gil, Javier (2007). "The influence of surface energy on competitive protein adsorption on oxidized NiTi surfaces". Biomaterials 28 (4): 586–94. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.040. PMID 17046057.