Bimetric theory

Bimetric theory refers to a class of modified mathematical theories of gravity (or gravitation) in which two metric tensors are used instead of one. Often the second metric is introduced at high energies, with the implication that the speed of light may be energy-dependent. There are several different bimetric theories, such as those attributed to Nathan Rosen (1909–1995)[1][2] or Mordehai Milgrom with Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND).[3]

Explanation

In general relativity (GR), it is assumed that the distance between two points in spacetime is given by the metric tensor. Einstein's field equation is then used to calculate the form of the metric based on the distribution of energy and momentum.

Rosen (1940) has proposed that at each point of space-time, there is a Euclidean metric tensor  in addition to the Riemannian metric tensor

in addition to the Riemannian metric tensor  . Thus at each point of space-time there are two metrics:

. Thus at each point of space-time there are two metrics:

The first metric tensor,  describes the geometry of space-time and thus the gravitational field. The second metric tensor,

describes the geometry of space-time and thus the gravitational field. The second metric tensor,  refers to the flat space-time and describes the inertial forces. The Christoffel symbols formed from

refers to the flat space-time and describes the inertial forces. The Christoffel symbols formed from  and

and  are denoted by

are denoted by  and

and  respectively. The quantities

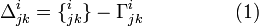

respectively. The quantities  are defined such that

are defined such that

Two kinds of covariant differentiation then arises:  -differentiation based on

-differentiation based on  (denoted by semicolon) and 3-differentiation based on

(denoted by semicolon) and 3-differentiation based on  (denoted by a slash). Ordinary partial derivatives are represented by a comma. Let

(denoted by a slash). Ordinary partial derivatives are represented by a comma. Let  and

and  be the Riemann curvature tensors calculated from

be the Riemann curvature tensors calculated from  and

and  , respectively. In the above approach the curvature tensor

, respectively. In the above approach the curvature tensor  is zero, since

is zero, since  is the flat space-time metric.

is the flat space-time metric.

From (1) one finds that though {:} and  are not tensors, but

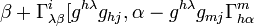

are not tensors, but  is a tensor having the same form as {:} except that the ordinary partial derivative is replaced by 3-covariant derivative. A straightforward calculation yields the Riemann curvature tensor

is a tensor having the same form as {:} except that the ordinary partial derivative is replaced by 3-covariant derivative. A straightforward calculation yields the Riemann curvature tensor

Each term on right hand side is a tensor. It is seen that from GR one can go to new formulation just by replacing {:} by  , ordinary differentiation by 3-covariant differentiation,

, ordinary differentiation by 3-covariant differentiation,  by

by  , integration measure

, integration measure  by

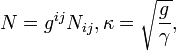

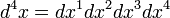

by  , where

, where  ,

,  and

and  . It is necessary to point out that having once introduced

. It is necessary to point out that having once introduced  into the theory, one has a great number of new tensors and scalars at one's disposal. One can set up other field equations other than Einstein's. It is possible that some of these will be more satisfactory for the description of nature.

into the theory, one has a great number of new tensors and scalars at one's disposal. One can set up other field equations other than Einstein's. It is possible that some of these will be more satisfactory for the description of nature.

The geodesic equation in bimetric relativity (BR) takes the form

It is seen from equation (1) and (2) that  can be regarded as describing the inertial field because it vanishes by a suitable coordinate transformation.

can be regarded as describing the inertial field because it vanishes by a suitable coordinate transformation.

The quantity  , being a tensor, is independent of any coordinate system and hence may be regarded as describing the permanent gravitational field.

, being a tensor, is independent of any coordinate system and hence may be regarded as describing the permanent gravitational field.

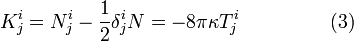

Rosen (1973) has found BR satisfying the covariance and equivalence principle. In 1966, Rosen showed that the introduction of the space metric into the framework of general relativity not only enables one to get the energy momentum density tensor of the gravitational field, but also enables one to obtain this tensor from a variational principle. The field equations of BR derived from the variational principle are

where

or

and  is the energy-momentum tensor.

is the energy-momentum tensor.

The variational principle also leads to the relation

Hence from (3)

which implies that in a BR, a test particle in a gravitational field moves on a geodesic with respect to

It is found that the theories BR and GR differ in the following cases:

- propagation of electromagnetic waves

- an external field of high density star

- the behaviour of the intense gravitational waves propagation through strong static gravitational field.

Note that other bimetric gravitational theories exist.

References

- ↑ The New Physics, Paul Davies, 1992, 526 pages, web: Books-Google-ak.

- ↑ "Nathan Rosen — The Man and His Life-Work", Technion.ac.il, 2011, web: Technion-rosen.

- ↑ Reinventing gravity: a physicist goes beyond Einstein, John W. Moffat, 2008, 272 pages, p.103, webpage: BG-6K.

External links

Bimetric Theory of Gravitational-Inertial Field in Riemannian and in Finsler-Lagrange Approximation Authors: J.Foukzon, S.A.Podosenov, A.A.Potapov, E.Menkova

![-\Gamma _{{j\alpha }}^{{\lambda }}]-\Gamma _{{j\beta }}^{{\lambda }}[g^{{hi}}g_{{h\lambda }},\alpha -g^{{hi}}g_{{m\lambda }}\Gamma _{{h\alpha }}^{{m}}-\Gamma _{{\lambda \alpha }}^{{i}}]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/b/d/2/8/bd2868a935ef09588548fcf78424dead.png)

![+\Gamma _{{\alpha \beta }}^{{\lambda }}[g^{{hi}}g_{{hj}},\lambda -g^{{hi}}g_{{mj}}\Gamma _{{h\lambda }}^{{m}}-\Gamma _{{j\lambda }}^{{i}}]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/8/8/e/e/88eea4039ba1ee87fe98be4502f5a8b0.png)