Bhikkhu

| Bhikkhu | |||||||||

Buddhist monks in Thailand | |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 比丘 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Native Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 和尚 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Burmese name | |||||||||

| Burmese | ဘိက္ခု | ||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||

| Tibetan | དགེ་སློང་ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||

| Thai | ภิกษุ | ||||||||

| RTGS | phiksu | ||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | 和尚 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Tamil name | |||||||||

| Tamil | துறவி turawi | ||||||||

| Sanskrit name | |||||||||

| Sanskrit | Bhikṣu | ||||||||

| Pali name | |||||||||

| Pali | Bhikkhu | ||||||||

| Nepali name | |||||||||

| Nepali | भिक्षु | ||||||||

A Bhikkhu (Pāli) or Bhikṣu (Sanskrit) is an ordained male Buddhist monastic.[1] A female monastic is called a Bhikkhuni (Skt: Bhikṣuṇī) Nepali: भिक्षुणी). The life of Bhikkhus and Bhikkhunis is governed by a set of rules called the patimokkha within the vinaya's framework of monastic discipline.[1] Their lifestyle is shaped to support their spiritual practice, to live a simple and meditative life, and attain Nirvana.[2] In the Vinaya monastic discipline, a man under the age of 20 cannot ordain as a bhikkhu but can ordain as a samanera (เณร); the female counterpart is samaneri.

Introduction

Bhikkhu may be literally translated as "beggar" or more broadly as "one who lives by alms". It is philologically analysed in the Pāli commentary of Buddhaghosa as "the person who sees danger (in samsara or cycle of rebirth)" (Pāli: Bhayaṃ ikkhatīti: bhikkhu). He therefore seeks ordination to release from it.[3] The Dhammapada states:[4]

| “ | [266-267] He is not a monk just because he lives on others' alms. Not by adopting outward form does one become a true monk. Whoever here (in the Dispensation) lives a holy life, transcending both merit and demerit, and walks with understanding in this world — he is truly called a monk. | ” |

In English literature before the mid-20th century, Buddhist monks were often referred to by the term bonze, particularly when describing monks from East Asia and French Indochina. This term is derived via Portuguese and French from the Japanese word bonsō for a priest or monk and has become less common in modern literature.[5]

Becoming a Bhikkhu/Bhikkhuni

In India, monasticism is part of the system of "vows of individual liberation".[3] These vows are taken by monks and nuns from the ordinary sangha, in order to develop personal ethical discipline.[3] In Mahayana Buddhism, the term "sangha" is, in principle, often understood to refer particularly to the Arya Sangha (Tib. mchog kyi tshogs, pronounced chokyi tsok) the "community of the noble ones who have reached the first bhumi". These, however, need not be monks and nuns.

The vows of individual liberation are taken in four steps. A lay person may take the five upāsaka (Pali and Sanskrit; feminine: upāsikā; Tibetan dge snyan/dge snyan ma, pronounced genyen/genyenma, "approaching virtue") vows. The next step is to enter the pabbajja (Srt: pravrajya, Tib. rab byung pronounced rabjung), or monastic way of life, which includes wearing monk's or nun's robes. After that, one can become a samanera (Pali; feminine: samaneri; Skt. śrāmaṇera/śrāmaṇeri, Tib. dge tshul/dge tshul ma, pronounced getshül/getshülma), or novice monk/nun. The last and final step is to take all the vows of a bhikkhu/bhukkhuni (Pali, Sanskrit: Bhikṣu/Bhikṣuṇīs, Tib. dge long/dge long ma>, pronounced gelong/gelongma) a "fully ordained monk/nun."

Monks and nuns take their vows for a lifetime. A monk can give bhikkhu vows back and return to home living,[6] and take the vows again later.[6] He can take them up to three times or seven times in one life; after that the sangha should not accept him.[7] In this way, Buddhism keeps the vows "clean". It is possible to keep them or to leave this lifestyle, but it is considered extremely negative to break these vows.

In Tibet, rabjung, getshül, gelong ordinations are usually taken at ages six, fourteen and twenty-one or older, respectively.

Robes

The special dress of ordained people, the robes, comes from the idea of wearing cheap clothes just to protect the body from weather and climate. Monks often make their own robes from cloth that is donated to them.[1] They shall not be made from one piece of cloth, but mended together from several pieces. Since dark red was the cheapest colour in Kashmir, the Tibetan tradition has red robes. In the south, yellow played the same role, though the color of saffron also had cultural associations in India; in East Asia, robe color varies from yellow to brown (Thailand, Theravada), red to purple (Burma, Theravada) and grey or black (e.g., Vietnam, Mahayana (Thien)).

The robes of getshül novices and gelong monks differ in various aspects, especially in the application of "holes" in the gelong dress. Some monks tear their robes into pieces and then mend these pieces together again. The rabjung novices shall not wear the "chö-göö", the yellow tissue worn during Buddhist teachings by both getshüls and gelongs.

In observance of the Kathina Puja, a special Kathina robe is made in 24 hours from donations by lay supporters of a temple. The robe is donated to the temple or monastery, and the resident monks then select from their own number a single monk to receive this special robe.[8]

Additional vows in the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions

In Mahayana traditions, a Bhikṣu may take additional vows not related to ordination, including the Bodhisattva vows, samaya vows, and others, which are also open to laypersons in most instances.

In addition, in some traditions there are forms of non-vinaya ordinations, the holders of which are not considered Bhikṣus. These included ordination into the "White Sangha" lineage of Tibetan yogis (Tib. naljorpa/naljorma, <rnal hbyor pa/ma>), and all of the ordination lineages of the various Japanese traditions.

Conclusion

"Ordination" in Buddhism is a cluster of methods of self-discipline according to the needs, possibilities and capabilities of individuals. According to the spiritual development of his followers, the Buddha gave different levels of vows. The most advanced method is the state of a bikshu(ni), a fully ordained follower of the Buddha's teachings. The goal of the bhikku(ni) in all traditions is to achieve liberation from suffering.

Talapoy

Buddhist monks were once called "Talapoy," from Portuguese talapão from Mon tala poi our lord. [9][10]

Gallery

-

Young Indian Buddhist monk in India.

-

A Theravada Buddhist monk in Laos

-

A Buddhist monk in China

-

A Buddhist monk in Taiwan

-

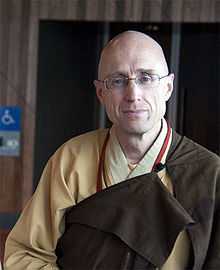

A Buddhist monk in the U.S. (Chinese Buddhism)

-

A Buddhist monk in Tibet

Monks in Japan

Saicho (AKA Dengyo) petitioned for a Mahayana Ordination Platform to be built in Japan. Permission was granted seven days after Dengyo died.[11] The platform was completed in 827 CE by Dengyo's disciple, Gishin.[11] Dengyo believed the 250 precepts were Hinayana, and that people should be ordained with the Mahayana Precepts of the Brahma Net Sutra. He stipulated that monastics remain on Mt.Hiei for 12 years of isolated training and follow the major themes of the 250 precepts- celibacy, non-harming, no intoxicants, vegetarian eating and reducing labor for gain. After 12 years monastics would them the Sravaka Vinaya precepts as a provisional, or supplemental, guideline to conduct themselves by when serving in non-monastic communities.[11]

During the Meiji Restoration, monastics in Japan were permitted through government pressure to marry and eat meat in an effort to secularise them and promote the new imperial Shinto as a state religion, Buddhists having been the administrative assistant of choice of the previous regime.[12][13]

Currently priests (lay religious leaders) in Japan choose to observe vows as appropriate to their family situation. Celibacy and other forms of abstaining are generally "at will" for varying periods of time.

Less often some people may choose a renunciate route (monks and nuns) and take personal vows of lifelong celibacy, vegetarian eating and voluntary simplicity. Following major themes of the personal-liberation discipline (Vinaya). In most sects strict living and discipline is followed during training periods and aspects of seminary but afterwards there is a considerable amount of individual approaches to religious lifestyle with much room for different opinions.

See also

| People of the Pali Canon | |

| Pali | English |

| Community of Buddhist Disciples | |

| Monastic Sangha | |

| Bhikkhu, Bhikkhunī Sikkhamānā Samaṇera, Samaṇerī |

Monk, Nun Nun trainee Novice (m., f.) |

| Laity | |

| Upāsaka and Upāsikā Gahattha, Gahapati Anagārika, Anagāriya |

Lay devotee (m., f.) Householder Layperson |

| Related Religions | |

| Samaṇa Ājīvika Brāhmaṇa Nigaṇṭha |

Wanderer Ascetic Brahmin Jainism |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Ly Guide to the Monks' Rules

- ↑ What is a bhikkhu?

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Resources: Monastic Vows

- ↑ Buddharakkhita, Acharya. "Dhammapada XIX - Dhammatthavagga: The Just". Access To Insight. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ Dictionary.com: bonze

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 how to become a monk?

- ↑ 05-05《律制生活》p. 0064

- ↑ Buddhist Ceremonies and Rituals of Sri Lanka, A.G.S. Kariyawasam

- ↑ "talapoin". Collins Concise English Dictionary © HarperCollins Publishers. WordReference.com. June 23, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2013. "Etymology: 16th Century: from French, literally: Buddhist monk, from Portuguese talapão, from Mon tala pōi our lord ..."

- ↑ Roberts, Edmund (Digitized October 12, 2007) [First published in 1837]. "Chapter XIX. Talapoys or Priests". Embassy to the Eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat : in the U. S. sloop-of-war Peacock ... during the years 1832-3-4. Harper & brothers. Page 297, image 304. OCLC 12212199. Retrieved 25 April 2012. "The Talapoys cannot be engaged in any of the temporal concerns of life; they must not trade or do any kind of manual labour, for the sake of a reward; they are not allowed to insult the earth by digging it. Having no tie, which unites their interests with those of the people, they are ready, at all times, with spiritual arms, to enforce obedience to the will of the sovereign."

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism, Soka Gakkai, 'Dengyo'

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/shinto/history/history_1.shtml#section_4

- ↑ http://www.buddhanet.net/nippon/nippon_partII.html

Further reading

- Inwood, Kristiaan. Bhikkhu, Disciple of the Buddha. Bangkok, Thailand: Thai Watana Panich, 1981. (No ISBN listed in the Library of Congress catalog.)

- Inwood, Kristiaan. Bhikkhu, Disciple of the Buddha, revised edition. Bangkok, Thailand: Orchid Press, 2005. ISBN 978-974-524-059-9.

External links

- The Buddhist Monk's Discipline Some Points Explained for Laypeople

- Thirty Years as a Western Buddhist Monk

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||