Betweenness centrality

Betweenness centrality is a measure of a node's centrality in a network. It is equal to the number of shortest paths from all vertices to all others that pass through that node. Betweenness centrality is a more useful measure (than just connectivity) of both the load and importance of a node. The former is more global to the network, whereas the latter is only a local effect. Development of betweenness centrality is generally attributed to sociologist Linton Freeman, who has also developed a number of other centrality measures.[1] The same idea was also earlier proposed by mathematician J. Anthonisse, but his work was never published.[2] Over the past few years, betweenness centrality has become a popular strategy to deal with complex networks. Applications include computer and social networks,[3][4] biology,[5][6] transport,[7] [8] scientific cooperation[9] and so forth.

Definition

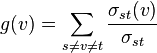

The betweenness centrality of a node  is given by the expression:

is given by the expression:

where  is the total number of shortest paths from node

is the total number of shortest paths from node  to node

to node  and

and  is the number of those paths that pass through

is the number of those paths that pass through  .

.

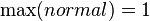

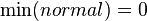

Note that the betweenness centrality of a node scales with the number of pairs of nodes as implied by the summation indices. Therefore the calculation may be rescaled by dividing through by the number of pairs of nodes not including  , so that

, so that ![g\in [0,1]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/a/5/f/2a5f25a02ffd4ddfbc76d431ddb4371b.png) . The division is done by

. The division is done by  for directed graphs and

for directed graphs and  for undirected graphs, where

for undirected graphs, where  is the number of nodes in the giant component. Note that this scales for the highest possible value, where one node is crossed by every single shortest path. This is often not the case, and a normalization can be performed without a loss of precision

is the number of nodes in the giant component. Note that this scales for the highest possible value, where one node is crossed by every single shortest path. This is often not the case, and a normalization can be performed without a loss of precision

which results in:

Note that this will always be a scaling from a smaller range into a larger range, so no precision is lost.

The load distribution in real and model networks

Model networks

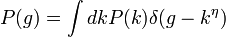

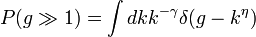

It has been shown that the load distribution of a scale-free network follows a power law given by a load exponent  ,[10]

,[10]

(1)

(1)

this implies the scaling relation to the degree of the node,

.

.

Where  is the average load of vertices with degree

is the average load of vertices with degree  . The exponents

. The exponents  and

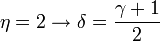

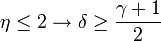

and  are not independent since equation (1) implies [11]

are not independent since equation (1) implies [11]

For large g, and therefore large k, the expression becomes

which proves the following equality:

The important exponent appears to be  which describes how the betweenness centrality depends on the connectivity. The situation which maximizes the betweenness centrality for a vertex is when all shortest paths are going through it, which corresponds to a tree structure (a network with no clustering). In the case of a tree network the maximum value of

which describes how the betweenness centrality depends on the connectivity. The situation which maximizes the betweenness centrality for a vertex is when all shortest paths are going through it, which corresponds to a tree structure (a network with no clustering). In the case of a tree network the maximum value of  is reached.[11]

is reached.[11]

This maximal value of  (and hence minimum of

(and hence minimum of  ) puts bounds on the load exponents for networks with non-vanishing clustering.

) puts bounds on the load exponents for networks with non-vanishing clustering.

In this case, the exponents  are not universal and depend on the different details (average connectivity, correlations, etc.)

are not universal and depend on the different details (average connectivity, correlations, etc.)

Real networks

Real world scale free networks, such as the internet, also follow a power law load distribution.[12] This is an intuitive result. Scale free networks arrange themselves to create short path lengths across the network by creating a few hub nodes with much higher connectivity than the majority of the network. These hubs will naturally experience much higher loads because of this added connectivity.

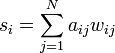

Weighted networks

In a weighted network the links connecting the nodes are no longer treated as binary interactions, but are weighted in proportion to their capacity, influence, frequency, etc., which adds another dimension of heterogeneity within the network beyond the topological effects. A node's strength in a weighted network is given by the sum of the weights of its adjacent edges.

With  and

and  being adjacency and weight matricies between nodes

being adjacency and weight matricies between nodes  and

and  , respectively.

Analogous to the power law distribution of degree found in scale free networks, the strength of a given node follows a power law distribution as well.

, respectively.

Analogous to the power law distribution of degree found in scale free networks, the strength of a given node follows a power law distribution as well.

A study of the average value  of the strength for vertices with betweenness

of the strength for vertices with betweenness  shows that the functional behavior can be approximated by a scaling form [13]

shows that the functional behavior can be approximated by a scaling form [13]

Algorithms

Calculating the betweenness and closeness centralities of all the vertices in a graph involves calculating the shortest paths between all pairs of vertices on a graph. This takes  time with the Floyd–Warshall algorithm, modified to not only find one but count all shortest paths between two nodes. On a sparse graph, Johnson's algorithm may be more efficient, taking

time with the Floyd–Warshall algorithm, modified to not only find one but count all shortest paths between two nodes. On a sparse graph, Johnson's algorithm may be more efficient, taking  time. On unweighted graphs, calculating betweenness centrality takes

time. On unweighted graphs, calculating betweenness centrality takes  time using Brandes' algorithm.[14]

time using Brandes' algorithm.[14]

In calculating betweenness and closeness centralities of all vertices in a graph, it is assumed that graphs are undirected and connected with the allowance of loops and multiple edges. When specifically dealing with network graphs, often graphs are without loops or multiple edges to maintain simple relationships (where edges represent connections between two people or vertices). In this case, using Brandes' algorithm will divide final centrality scores by 2 to account for each shortest path being counted twice.[14]

Another algorithm generalizes the Freeman's betweenness computed on geodesics and Newman's betweenness computed on all paths, by introducing an hyper-parameter controlling the trade-off between exploration and exploitation. The time complexity is the number of edges times the number of nodes in the graph.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ Freeman, Linton (1977). "A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness". Sociometry 40: 35–41. doi:10.2307/3033543.

- ↑ Newman, M.E.J. (2010). Networks: An Introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199206650.

- ↑ Brandes, Ulrik (2008). "On variants of shortest-path betweenness centrality and their generic computation". Social Networks 30: 136–145. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2007.11.001.

- ↑ Cuzzocrea, Alfredo; Papadimitriou, Alexis; Katsaros, Dimitrios; Manopoulus, Yanis (2012). "Edge betweenness centrality: A novel algorithm for QoS-based topology control over wireless sensor networks". Journal of Network and Computer Applications 35: 1210–1217. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2011.06.001.

- ↑ Estrada, Ernesto (2007). "Characterization of topological keystone species Local, global and meso-scale centralities in food webs". Ecological Complexity 4: 48–57.

- ↑ Martin Gonzalez, Ana M.; Dalsgaard, Bo; Olesen, Jens M. (2010). "Centrality measures and the importance of generalist species in pollination networks". Ecological Complexity 7: 36–43.

- ↑ Wang, Jiaoe; Huihui, Mo; Wang, Fahui; Jin, Fengjun (2011). "Exploring the network structure and nodal centrality of China’s air transport network: A complex network approach". Journal of Transport Geography 19: 712–721.

- ↑ Rodriguez-Deniz, Hector (2012). "Using SAS® to Measure Airport Connectivity: An Application of Weighted Betweenness Centrality for the FAA National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS)". Proceedings of the SAS Global Forum 2012, Paper 162-2012.

- ↑ Abassi, Alireza; Hossain, Liaquat; Leydesdorff, Loet (2012). "Betweenness centrality as a driver of preferential attachment in the evolution of research collaboration networks". Journal of Informetrics 6: 403–412.

- ↑ K. I. Goh, B. Kahng, D. Kim (12 Dec 2001). "Universal Behavior of Load Distribution in Scale-Free Networks". Physical Review Letters. 87.278701 (27). doi:10.1103/physrevlett.87.278701.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 M. Barthélemy Eur. Phys. J. B 38, 163–168 (2004)

- ↑ Kwang-Il Goh, Eulsik Oh, Hawoong Jeong, Byungnam Kahng, and Doochul Kim. PNAS (2002) vol. 99 no. 2

- ↑ A. Barrat, M. Barthelemy, R. Pastor-Satorras, and A. Vespignani. PNAS (2004) vol. 101 no. 11

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Ulrik Brandes. A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality (PDF).

- ↑ Amin Mantrach et al. The sum-over-paths covariance kernel: A novel covariance measure between nodes of a directed graph", Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, IEEE Transactions, 32(6), pages 1112--1126, 2010.