Berber orthography

Berber orthography is the orthography of Berber languages. Most Berber languages were originally unwritten,[1][2] preserved through oral use in rural areas, isolated from urban hubs.[2] Berber scholars (like Al-Youssi and Al-Mokhtar Soussi) wrote in the more prestigious Arabic language, rather than their vernacular.[2] Currently there are three writing systems in use for Berber languages: the Berber Latin alphabet, Tifinagh, and the Arabic script.[3] Different groups in North Africa have different preferences of writing system, often motivated by ideology and politics.[3]

Tifinagh

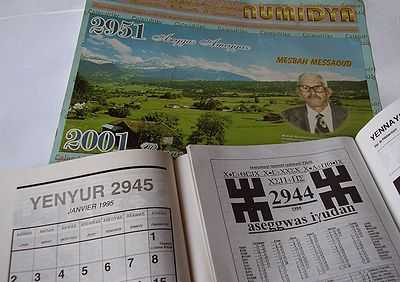

Neo-Tifinagh,[nb 1] a resurrected version of an alphabetic script found in historical engravings, is currently the de jure writing system for Tamazight in Morocco,.[4] The script was made official by a Dahir of King Mohammed VI, based on the recommendation of IRCAM.[3] It was recognized in the Unicode standard in June 2004.[5]

Tifinagh was chosen to be official after consideration of its univocity (one sound per symbol, allowing regional variation[6]), economy, consistency, and historicity.[6] Significantly, Tifinagh avoids negative cultural connotations of the Latin and Arabic scripts.[7]

Tifinagh is preferred by young people as a symbol of identity and has popular support.[3][8] It is especially popular for symbolic use, with many books and websites written in a different script featuring logos or title pages using Neo-Tifinagh. However, until recently virtually no books or websites were published in this alphabet, with activists primarily favoring Latin scripts for serious usage.

Tifinagh has been criticized for not being practical to implement, as well as being Kabyle-centric and not historically authentic.[9][10] Despite being used to teach children Tamazight in Moroccan schools since September 2003,[11] Tifinagh is not currently found on public signs or buildings in Morocco.[8] Following the Tifinagh Dahir road signs were installed in the Riffian city of Nador in Arabic and Tifinagh, but these were removed by security forces in the middle of the night soon after.[3]

The Moroccan state arrested and imprisoned people using this script during the 1980s and the 1990s,[12] but currently Morocco is the only country in which Tifinagh has official status.

Latin

The Latin script has its origins in French colonialism.[13] French missionaries and linguists found the Arabic script inconvenient, so they adapted the Latin alphabet to various Berber languages and Arabic vernaculars.[13] While the established body of literature in the Arabic script was a barrier to wider adoption of the Latin script, it caught on among the French-educated minority, particularly in Algeria.[13] Since independence, the Latin alphabet has been largely favored by the intelligentsia, especially in Kabylie where the Berberists are largely pro-Westernization and French-educated.[13] A standard transcription for the Kabyle language was established in 1970, and most other Northern Berber dialects have to varying extents published literature in the Latin alphabet.[13]

The Latin alphabet has been preferred among Amazigh linguists and researchers, and also has a great deal of established writing, including newspapers, periodicals, and magazines.[3][14][15] It is more popular in Algeria than Morocco, but prevalent in the Riffian area.[15] It is backed by the Amazigh elite, but is vehemently opposed by the Moroccan pro-Arab establishment.[3] The Latin script is far more ensconced in the Kabyle dialect than in Tamazight.[16]

The orthography used in most modern printed works is the Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales (INALCO) standard, designed for phonemicity.[13] Older systems from the colonial French era are still found in place names and personal names.[13] The older colonial system showed marked influence from French, for instance writing /u, w/ as ⟨ou⟩ and /sˤ/ as ⟨ç⟩, and was inconsistent in marking many Berber sounds, for instance writing /ʕ/ as a circumflex over the vowel, and often leaving emphatics unmarked.[13]

Arabic

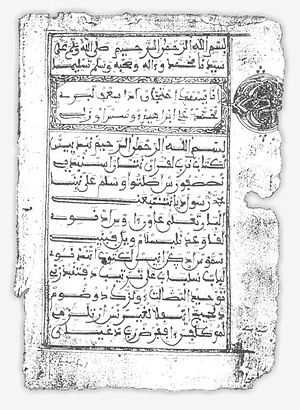

The Arabic script is the traditional script for written Berber, and is the predominant orthography for Berber literature for the general public in Morocco.[15][17] Some Tamazight newspapers, periodicals, and magazines are written in Arabic script, although the Latin alphabet is preferred.[14] Islamists support the use of Arabic script, wanting Morocco to be an Islamic country that shuns Western secularism and colonial practices.[18] Amazigh activists, however, eschew Arabic script which is generally unpopular among Berbers who believe it is symptomatic of North African governments' pan-Arabist views.[3]

The oldest examples of Berber written in the Arabic script date back to the 10th century, and the youngest examples of medieval Berber spelling date to the 14th century.[19] The spelling was remarkably consistent, unlike old orthographies for European languages, suggesting deliberate design.[19] Older manuscripts show more consistency, while newer ones display corruption from copying by non-Berberphones, or by speakers of Shilha who were familiar with the different Arabic orthography for Shilha that has been in use from the 16th century to the present.[19]

Notes

- ↑ Linguists and historians tend to be specific in distinguishing between the millennia-old Berber abjad used by the Tuareg to a limited extent and found in some historical engravings and which is 'Tifinagh'; and the 'Neo-Tifinagh' alphabet which is based on the abjad but marks vowels and distinguishes more consonants. The Neo-Tifinagh script was developed and computerized in the 20th century mainly by Moroccan and Algerian researchers, some of whom were based in Europe. It has been used since the early 1970s in Berber publications, see Chaker (1996:4).

References

- ↑ Abdel-Massih (1971:viii)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ben-Layashi (2007:166)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Larbi, Hsen (2003). "Which Script for Tamazight, Whose Choice is it ?". Amazigh Voice (Taghect Tamazight) (New Jersey: Amazigh Cultural Association in America (ACAA)) 12 (2). Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- ↑ Aflou, Lyes (2007). "Amazigh writing system adaptable to the modern age". Maghrebia. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- ↑ Balkassm, Hasan (2008). "Legal and constitutional status of Amazigh language in Morocco & North Africa". International Expert Group Meeting on Indigenous Languages (UNPFII). Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bouhjar (2008:2)

- ↑ Brenzinger (2007:127)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 El Aissati (2001:12–13)

- ↑ "Interview met Karl-G. Prasse". Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ↑ Bounfour, Abdellah (2004). "The Current State of Tamazight in Morocco". Tamazgha Paris. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Tifinagh alphabet and Berber languages". Omniglot. S. Ager. n.d. Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- ↑ (French) Idbalkassm, Hassan (1996). "Rapport sur le calvaire de l’écriture en Tifinagh au Maroc". Amazigh World. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Souag (2004)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Brenzinger (2007:128)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Chaker (1996:4–5)

- ↑ "Tifinagh Script Issue". January 25, 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Berber Language Page". Michigan: African Studies Center. n.d. 5 Orthographic Status. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ↑ Brenzinger (2007:126)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Prasse (2000), p. 357.

Bibliography

- Abdel-Massih, Ernest T. (1971). A Course in Spoken Tamazight. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. ISBN 0-932098-04-5.

- Ben-Layashi, Samir (2007). "Secularism in the Moroccan Amazigh Discourse". The Journal of North African Studies (Routledge) 12 (2): 153. doi:10.1080/13629380701201741. ISSN 1362-9387. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- Bouhjar, Aicha (2008). "Amazigh Language Terminology in Morocco or Management of a 'Multidimensional' Variation". International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC). Rabat: IRCAM. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- Brenzinger, Matthias (2007). Language Diversity Endangered. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017049-3.

- (French) Chaker, Salem (1996). "Tira n Tmaziɣt – propositions pour la notation usuelle a base latine du berbere". Problèmes en suspens de la notation usuelle à base latine du berbère. INALCO. Retrieved December 20, 2009. Unknown parameter

|city=ignored (help) - El Aissati, Abderrahman (2001). "Ethnic identity, language shift and The Amazigh voice in Morocco and Algeria". Race, Gender & Class. an Interdisciplinary and Multicultural Journal 8 (3). Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- (French) Prasse, Karl G. (2000). Études berbères et chamito-sémitiques: mélanges offerts à Karl-G. Prasse. ISBN 90-429-0826-2.

- Souag, Lameen (2004). "Writing Berber Languages: a quick summary". L. Souag. Archived from the original on July 30, 2005. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||