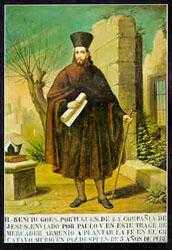

Bento de Góis

| Bento de Góis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1562 Vila Franca do Campo, Azores, Kingdom of Portugal |

| Died |

April 11, 1607 (aged 44–45) Suzhou, Gansu, China |

| Nationality | Portuguese |

| Occupation | Jesuit missionary, explorer |

| Known for | First European to travel overland from India to China. |

Bento de Góis (1562, Vila Franca do Campo, Azores, Portugal - 11 April 1607, Suzhou, Gansu, China), was a Portuguese Jesuit Brother, Missionary and explorer. His name is commonly given in English as Bento de Goes[1][2] or Bento de Goës;[3] in the past, it has also been Anglicized as Benedict Goës.[4]

He is mainly remembered as the first known European to travel overland from India to China, via Afghanistan and the Pamirs. Inspired by controversies among the Jesuits as to whether the Cathay of Marco Polo's stories is the same country as China, his expedition conclusively proved that the two countries are one and the same, and, according to Henry Yule, made "Cathay... finally disappear from view, leaving China only in the mouths and minds of men".[5]

Biography

Early life

Góis went to Portuguese India as a soldier in the Portuguese army. In Goa he entered the Society of Jesus as a lay brother (in 1584), offering himself to work for the Mughal Mission. As such, in 1595, he accompanied Jerome Xavier and Manuel Pinheiro to Lahore. For the third time Emperor Akbar had requested that Jesuits be sent to his court. Goes returned to Goa in 1601. According to Matteo Ricci, these experiences allowed Góis to become fluent in Persian language, and a good knowledge of "Saracen" (i.e., Muslim) customs.[3]

The riddle of Cathay

Góis is best remembered for his long exploratory journey through Central Asia, under the garb of an Armenian merchant, in search of the Kingdom of Cathay. Generated by accounts made by Marco Polo, and later by the claims of Ruy Gonzales de Clavijo,[6] reports had been circulating in Europe for over three centuries of the existence of a Christian kingdom in the midst of Muslim nations. After the Jesuit missionaries, led by Matteo Ricci, had spent over 15 years in south China and finally reached Beijing in 1598, they came to strongly suspect that China is Cathay; this belief was strengthened by the fact that all "Saracen" (i.e., Central Asian Muslim) travelers whom Ricci and his companions met in China told them that they are in Cathay.[3]

The Jesuit leadership in Goa had been informed by letters from Jesuits in China that China is Cathay (but that there were no Christians there at the time). At the same time, the Jesuits stationed at the Mughal court (in particular Jerome Xavier himself) were told by visiting merchants that one could reach Cathay via Kashgar, and that there were plenty of Christians in Cathay, which convinced Xavier that Cathay is, in fact, the Kingdom of Prester John, rather than the Ming China.[7]

(In retrospect, the Central Asian Muslim informants' idea of the Ming China being a heavily Christian country may be explained by numerous similarities between Christian and Buddhist ecclesiastical rituals - from having sumptuous statuary and ecclesiastical robes to Gregorian chant - which would make the two religions appear externally similar to a Muslim merchant.[8] More over, there had been in fact a large number of (mostly Nestorian) Christians in China and Moghulistan through the Yuan era (i.e., until over a century before Goís' days). At the time when Goís' expedition was prepared, the most widely read account of "Cathay" in the Persian- and Turkic-speaking Muslim world was perhaps the travelogue of Ghiyāth al-dīn Naqqāsh from 1420-1422;[9] it does not mention any Christians within the border of the Ming China, but some editions of it do mention "infidels worshiping the cross" in Turfan and Cumul.[10])

After some amount of communications between Xavier, the order's superiors in Goa (Nicolo Pimenta (Niccolò Pimenta), the Father Visitor, was in charge there[3]), and the authorities in Europe, it was decided to send an expedition overland from India to the Cathay about which visitors to the Mughals' Agra had told the Jesuits, to find out what that country really was. Góis was chosen as the most suitable person for this expedition, as a man of courage and good judgment, well familiar with the region's language and customs. Akbar approved of the plans as well; he issued Góis with letters of safe conduct to be used during the part of the trip within the Mughal Empire, and provided partial funding for the expedition.[3][7]

Góis goes to Cathay

Bento Góis left Agra for Lahore in late 1602 or early 1603 (sources differ[11]), and in February 1603 he left Lahore with the annual caravan bound for Kashgaria's capital Yarkand. His cover identity was that of an Armenian merchant with a somewhat unlikely name Abdullah Isái.[1] He was accompanied by two Greeks, chosen by Xavier: a priest named Leo Grimano (who only traveled with Bento until Kabul) and a merchant named Demetrios, who also separated from Bento in Kabul, but later rejoined him in Yarkand. Instead of the four servants given to him in Agra, in Lahore he hired a real Armenian residing in that city, named Isaac. Isaac went along with Góis until the very end.[12]

Traveling via Peshawar, the caravan reached Kabul, where the caravan members spent several months. While in Kabul, Góis met "Agahanem", the sister of the ruler of Kashgaria, who was also the mother of the current ruler of Hotan. She was returning to her homeland from a Hajj to Mecca, and had run out of money. The Jesuit lent her some funds, which she later repaid with quality jade.[13]

From another traveler he met, Góis learned about the existence of "a city called Capperstam, into which no Mahomedan is allowed to enter" (according to Henry Yule, a reference to the region of Kafiristan), and got a taste of Kafir wine, which he found quite similar to the European product.[14]

From Kabul, Bento Góis and Isaac went north, crossing the Hindu Kush. Having left the domain of the Moghuls, and entered the territory under the authority (at least nominal) of the Khan of Samarcand, Ferghana, and Bukhara,[15] they made a stop in Taloqan ("Talhan") in today's northern Afghanistan. The area was in turmoil, with the "Calcia" people, "blond... like the Belgians" being in rebellion against the Bukharan rulers.[16] Having passed through the land of the Calcia rebels with only minor losses, Bento's caravan continued eastward, on dangerous roads across the Pamirs. Neither Henry Yule in 1866, nor C. Wessels in 1924 were able to identify most of the place names mentioned by Góis, but mentioned that this was probably the only published account of a European crossing the region between the expedition of Marco Polo and the 19th century.[17][18] The caravan reached Yarkand ("Hiarchan") in November 1603.

Yarkand had been the capital of Kashgaria (westerm Tarim Basin) since the days of Abu Bakr Khan (ca. 1500).[19] Bento and Isaac spent a year there, waiting for the formation and departure of a caravan to Cathay. They knew that every few years a caravan like this would leave Yarkand, composed primarily of local merchants, carrying jade to the capital of Cathay (i.e., Beijing) under the guise of "tribute" to the Ming Emperor from various Central Asian rulers. According to the custom, the emperor would choose the best jade for himself, generously reimbursing the Kashgarians, and the rest of the jade they would be allowed to sell to Beijing merchants. During this time, Bento also made a side trip to Hotan, where his earlier loan to the principality's Queen Mother was generously rewarded with jade.[20]

The Jesuit impressed the Yarkand-based ruler of Kashgaria Muhammad Sultan (r. 1592-1609),[21] a descendant of Sultan Said Khan[22] and a murid of Khoja Ishaq,[23] with a gift of a mechanical watch, and obtained from him a document for entry into the "Kingdom of Cialis" further east, which was ruled by Muhammad's son.[24]

The jade-laden "tribute" caravan left Yarkand in November 1604. They made a stop in Aksu, Xinjiang, which was still within Kashgarian Kingdom, and had Muhammad Sultan's 12-year-old nephew as its nominal ruler. The Jesuit befriended the boy with some sweets and a performance of a European dance, and his mother, with a variety of small gifts.[25]

The caravan then crossed the "desert of Caracathai", or "the Black Land of the Cathayans" which, as Bento learned, was so named after the "Cathayans [who] had lived there for a long time".[26] The next major stop was the small, but strongly fortified city of Cialis, where the travelers spent three months, as the caravan's chief waited for more merchants to join.[27] Although it follows from the geography of the route (between Kucha and Turpan) that Cialis had to be located somewhere within today's Bayin'gholin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, its identity has been a subject of speculation among later historians.[28] Some thought that it's the city known to us as Korla (today, the capital of the prefecture),[29] while others opined for Karashar, some 50 km farther to the northeast.[30]

It was in Cialis that Bento's caravan met with another caravan, returning from Beijing to Kashgaria. As the luck would have it, during their stay in Beijing - "Cambalu", in (Italianized) Turkic - the Kashgarians had resided at the same facility for accommodating foreign visitors where Matteo Ricci, the first Jesuit to reach the Chinese capital, had been detained for a while. The returning Kashgarians told Bento Góis what they knew about this new, unusual species of visitors to China, and even showed him a piece of scrap paper with something written in Portuguese, apparently dropped by one of the Jesuits, which they had picked as a souvenir to show to their friends back home. Góis was overjoyed, now pretty sure that the China Jesuits had been right identifying Marco Polo's Cathay as China, and Cambalu as Beijing.[31]

Stuck in Suzhou

Via Turpan and Hami, Bento's caravan arrived to the Chinese border at Jiayuguan, and soon obtained the permission to cross the Great Wall and to proceed to Suzhou (now, Jiuquan City center) - the first city within the Ming Empire, which they entered near the end of 1605. After three years and 4,000 miles of arduous travel, Bento and Isaac weren't doing too bad - they had 13 horses, five hired servants, and two boys that Bento had redeemed out of slavery. They carried plenty of precious jade with them, and, most importantly, both travelers were in good health.[32] But here his luck ran out. The Ming Empire had fairly restrictive rules for foreigners' entry into the country, and it would take many months before the Central Asian merchants/"ambassadors" would be allowed to proceed into the interior of the country. In the meantime, Bento and Isaac, virtually imprisoned in the border city, had to spend their assets to feed themselves at the exorbitant prices prevailing there. Góis wrote a letter to the Jesuits in Beijing asking them to find a way to get him out of Suzhou, but it wasn't delivered, as he did not know the address of his colleagues in Beijing, and apparently could not even ask anyone to have the letter addressed in Chinese. On their end, the Beijing Jesuits (informed about de Góis expedition by his Goa superiors) were making inquiries about him from people coming from the west, but could not learn anything either, since they did not know his "Armenian" name, or maybe just were asking the wrong people.[33]

Bento's second letter, sent around the Easter time of 1606, made it to Beijing in mid-November. Despite the winter weather, Ricci promptly sent a Chinese Jesuit Lay Brother, named Giovanni Fernandes[34] to his rescue.[35]

Despite inclement weather and the theft of many of his supply by his servant in Xi'an, Fernandes made it to Suzhou in late March, 1607 - and found Bento sick, and almost at the point of death. (Ricci says that he may have been poisoned.) The intrepid traveler died 11 days after Fernandes' arrival, and the other members of his caravan, pursuant to their "diabolical custom", divided his property among themselves.[36]

It took several months of legal efforts for Giovanni and Isaac to recover some of Bento's property and papers from his former caravan mates. Unfortunately, his travel journal - which he was said to have kept meticulously - had been destroyed by the "Saracen" caravan people, supposedly because it also contained records of the amounts of funds some of them owed to him. Therefore, our records of his expedition are very sketchy, based primarily on the several surviving letters (several sent back to India, and the last one, to Ricci), and on information obtained by Ricci from Isaac and Giovanni.[37][38]

Isaac and Giovanni buried Bento in as Christian manner as it was possible under the circumstances, and went to Beijing. After being debriefed by Ricci during a month's stay in Beijing, Isaac returned to India via Macau and the Strait of Singapore, not without some more adventures on the way.[39]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Bento de Goes", in: Goodrich, Luther Carrington; Fang, Zhaoying (1976). Dictionary of Ming biography, 1368-1644. Volume 1. Columbia University Press. pp. 472–473. ISBN 0-231-03801-1.

- ↑

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Gallagher (trans.) (1953), p. 499-500.

- ↑ Henry Yule (1866)

- ↑ Henry Yule (1866), p. 530.

- ↑ González de Clavijo, who met Chinese envoys in Samarkand in 1404-1405, reported that the then "emperor of Cathay" (i.e. the Yongle Emperor) had recently converted to Christianity: González de Clavijo, Ruy; Markham, Clements R. (translation and comments) (1859), Narrative of the embassy of Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo to the court of Timour at Samarcand, A.D. 1403-6 (1859), pp. 133–134. There is also a 1970 reprint, with the same pagination).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Yule, pp. 534-535

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 500; Yule, pp. 551-552

- ↑ Bellér-Hann 1995, pp. 3,5–6,10

- ↑ Bellér-Hann., Ildikó (1995), A History of Cathay: a translation and linguistic analysis of a fifteenth-century Turkic manuscript, Bloomington: Indiana University, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, p. 159, ISBN 0-933070-37-3

- ↑ Yule, p. 537

- ↑ Gallagher, p 501, or Yule, p. 553

- ↑ Gallagher, p 502, or Yule, p. 556

- ↑ Gallagher, pp. 501-502, or Yule, p. 554

- ↑ Wessels, p. 19

- ↑ "Calcia" is apparently an Italianized spelling variant of "Galcha" (Wessels, p. 19; Galchas in Encyclopædia Britannica (1911)). While "Galcha" is an archaic term that referred a broad number of people, which cannot be directly mapped to any single modern ethnic group, it was described by at least one author (Sinor, Denis (1997). The Uralic and Altaic Series. Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 0-7007-0380-2.) as a name used by lowland Tajiks for the Pamiri people.

- ↑ Yule, p. 539

- ↑ Wessels, pp. 22-23

- ↑ Yule. p. 546

- ↑ Gallagher, pp. 506-507

- ↑ Millward 2007 Ricci records the name of the ruler as "Mafamet Can" or "Mahamethin" (Gallagher, pp. 502, 506), and Yule (p. 546) rendered the name as Mahomed Sultan

- ↑ Yule, p. 546

- ↑ Millward 2007

- ↑ Yule, p. 547

- ↑ Gallagher, pp. 509-510

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 510

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 511; Yule, p. 574. "Cialis" is apparently Ricci's Italianized spelling of a Turkic name that could have been "Chalish"; see e.g. "The Dictionary of Ming Biography, p. 471.

- ↑ A number of proposed locations are listed in Wessels, p. 35

- ↑ Wessels, p. 35

- ↑ Yule, p. 575, following d'Anville

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 512; Yule, p. 577

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 515; Yule, p. 583

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 516; Yule, p. 584

- ↑ The Chinese Jesuit's Christian name is anglicized as "John Ferdinand" in Yule (p. 586). Neither Ricci nor other sources give his original Chinese name.

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 516; Yule, p. 586; Vincent Cronin. (1984), The Wise Man from the West, p.241-242.

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 519

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 518-59; Yule, pp. 536-537

- ↑ Wessels, p. 31

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 521

Bibliography

- Wessels, Cornelius (1992). Early Jesuit travellers in Central Asia, 1603-1721. Asian Educational Services. pp. 1–42. ISBN 81-206-0741-4. (Reprint of the 1924 edition)

- Bernard, H., Le frère Bento de Goes chez les musulmans de la Haute-Asie, Tientsin, 1934.

- Bishop, G.,In Search of Cathay, Anand, 1998.

- Cronin, V., The Wise Man From the West, Harvill Press, 2003

- Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press, p. 86, ISBN 0-231-13924-1

- Trigault, Nicolas S. J. "China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Mathew Ricci: 1583-1610". English translation by Louis J. Gallagher, S.J. (New York: Random House, Inc. 1953). This is an English translation of the Latin work, De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas based on Matteo Ricci's journals completed by Nicolas Trigault. In particular, Book Five, Chapter 11, "Cathay and China: The Extraordinary Odyssey of a Jesuit Lay Brother" and Chapter 12, "Cathay and China Proved to Be Identical." (pp. 499–521 in 1953 edition). There is also full Latin text available on Google Books.

- "The Journey of Benedict Goës from Agra to Cathay" - Henry Yule's translation of the relevant chapters of De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas, with detailed notes and an introduction. In: Yule (translator and editor), Sir Henry (1866). Cathay and the way thither: being a collection of medieval notices of China. Issue 37 of Works issued by the Hakluyt Society. Printed for the Hakluyt society. pp. 529–596.

- The report of a Mahometan Merchant which had beene in Cambalu: and the troublesome travell of Benedictus Goes, a Portugall Jesuite, from Lahor to China by land, thorow the Tartars Countreyes, A.D. 1598, in Purchas his Pilgrimes, Volume XII (1625), p. 222. The book is available in a variety of formats on archive.org, including OCR-ed text. The book also appears on Google Books, but only in snippet view.

|