Benomyl

| Benomyl | |

|---|---|

| |

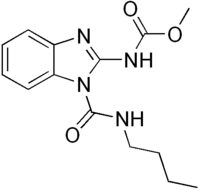

| IUPAC name Methyl [1-[(butylamino)carbonyl]-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl]carbamate | |

| Other names Benomyl | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 17804-35-2 |

| PubChem | 28780 |

| ChemSpider | 26771 |

| UNII | TLW21058F5 |

| KEGG | C10896 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:3015 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL327919 |

| Jmol-3D images | Image 1 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C14H18N4O3 |

| Molar mass | 290.32 g mol−1 |

| Melting point | 290 °C |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |

| Infobox references | |

Benomyl (also marketed as Benlate) is a fungicide introduced in 1968 by DuPont. It is a systemic benzimidazole fungicide that is selectively toxic to microorganisms and invertebrates, especially earthworms. Benomyl binds to microtubules, interfering with cell functions, such as meiosis and intracellular transportation. The selective toxicity of benomyl as a fungicide is possibly due to its heightened effect on fungal rather than mammalian microtubules.

Due to the development and worldwide prevalence of resistance of parasitic fungi to benomyl, it and similar pesticide compounds became largely ineffective. High legal costs associated with it caused DuPont to cease its production in 2001 after 33 years on the market, and voluntarily requested cancellation for its registration.[1][2] However, as DuPont's patents expired long ago and in some countries benomyl's registration has not been revoked, other manufacturers still produce it.

Toxicity

Benomyl is of such a low toxicity to mammals, it has been impossible to administer doses large enough to establish an LD50. It has an arbitrary LD50 of "greater than 10,000 mg/kg/day for rats". Skin irritation may occur through industrial exposure, and florists, mushroom pickers and floriculturists have reported allergic reactions to benomyl.

In a laboratory study, dogs fed benomyl in their diets for three months developed no major toxic effects, but did show evidence of altered liver function at the highest dose (150 mg/kg). With longer exposure, more severe liver damage occurred, including cirrhosis.

The US Environmental Protection Agency classified benomyl as a possible carcinogen. Carcinogenic studies have produced conflicting results. A two-year experimental study on mice has shown it "probably" causes an increase in liver tumours. The British Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries and Food took the view this was brought about by the hepatotoxic effect of benomyl.

In 1993, the Observer, a UK national newspaper, published a series of articles alleging a possible link between exposure of pregnant mothers to benomyl and their children being born without eyes (anophthalmia) or with related syndromes, including reduced eyes and blindness, due to severe damage of the optic stem. The newspaper cited a number of suspected clusters in the UK that may have corresponded to areas of benomyl use. Studies have shown eye defects can occur at relatively high doses. A test in which rats were dosed orally demonstrated evidence of microphthalmia at dose levels of 62.5 mg/kg and above.

In regards to occupational exposures to benomyl, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration has set a permissible exposure limit of 15 mg/m3 for total exposure over an eight-hour time-weighted average, and 5 mg/m3 for respiratory exposures.[3]

Birth defects

In 1996, a Miami jury awarded US$ 4 million to a child whose mother was exposed in pregnancy to Benlate. The child was born without eyes. The mother had been exposed to an unusually high dose of Benlate through her occupation, during pregnancy. An important issue in the case was whether the timing of exposure - during the formation of the optic nerve in the foetus - was critical, as well as the magnitude of exposure. The case was prosecuted by the Ferraro Law Firm.[4][5]

In October 2008, DuPont paid confidential settlements to two New Zealand families whose children were born with either anophthalmia or other birth defects.[6] The mother of one of the children had been exposed to Benlate while working as a Christchurch parks worker before his birth.[citation needed]

A Benlate compensation case involving an English boy from Essex born without eyes is also due to be heard shortly in the US.[citation needed]

Environmental effects

Benomyl binds strongly to soil and does not dissolve in water to any great extent. It has a half-life in turf of three to six months, and in bare soil, a half-life of six months to one year.

In 1991, DuPont issued a recall of its Benlate 50DF formula due to suspected contamination with the herbicide atrazine. In the wake of the recall, many US growers blamed Benlate 50DF for destroying millions of dollars worth of crops. Growers filed over 1900 damage claims against DuPont, mostly involving ornamental crops in Florida. Subsequent testing by DuPont determined the recalled product was not contaminated with atrazine. The reason for the alleged crop damage is unclear. The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services suggested Benlate was contaminated with dibutylurea and sulfonylurea herbicides.

After several years of legal argument, DuPont paid out about US$750 million in damages and out-of-court settlements. By 1993, a coalition of farm worker and environmental groups came together to form "Benlate Victims Against DuPont", a group which called for a nation-wide boycott of DuPont products.

After carrying out tests, DuPont denied Benlate was contaminated with dibutylurea and sulfonylureas and stopped compensation pay-outs. In 1995, a Florida judge rejected a complaint from the Florida Department of Agriculture that had alleged such a link.

Cellular biology

Benomyl is used in molecular biology to study the cell cycle in yeast; in fact, the name of the protein class "Bub" (Bub1, etc.) comes from their mutant in which budding was uninhibited by benomyl.

References

- ↑ EPA: Federal Register: Benomyl; Cancellation Order

- ↑ DuPont Withdraws Benlate from Market PANNA 7may01

- ↑ "Benomyl". NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 4, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ↑ Wilson, Stephanie. "The People's Champion". Haute Living. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ↑ Ashton, John (August 18, 1996). "Blind Justice: John has no eyes. But now he has hope.". Night and Day. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ↑ Hill, Ruth (2008-08-18). "Chemical giant pays out for birth defects". The Dominion Post (Fairfax New Zealand Limited). Retrieved 2008-07-18.

Further reading

- Tomlin, C., (Ed.) The Pesticide Manual, 10th Edition, British Crop Protection Council/Royal Society of Medicine, 1994.

- Benomyl, Extoxnet, Pesticide Management Education Program, Cornell University, NY, May 1994.

- World Health Organisation, WHO/PCS/94.87 Data sheet on benomyl, Geneva, 1994.

- Whitehead, R (Ed) The UK Pesticide Guide, British Crop Protection Council/CAB International, 1996.

- Thomas, M.R. and Garthwaite, D.G., Orchards and Fruit Stores in Great Britain 1992, Pesticide Usage Survey Report 115, Central Science Laboratory, 1994.

- Thomas, M.R. and Garthwaite, D.G., Outdoor Bulbs and Flowers in Great Britain 1993, Pesticide Usage Survey Report 121, Central Science Laboratory, 1995.

- Garthwaite, D.G., Thomas, M.R., Hart, M.J, and Wild, S, Outdoor vegetable crops in Great Britain 1995, Pesticide Usage Survey Report 134, Central Science Laboratory, 1997.

- Thomas, M.R. and Garthwaite, D.G., Hardy Nursery Stock in Great Britain 1993, Pesticide Usage Survey Report 120, Central Science Laboratory, 1995.

- Benomyl evaluation No. 57, MAFF, July 1992, pp109–111.

- More problems for Benlate? Agrow, 13 March 1992, p13.

- List of Chemicals Evaluated for Carcinogenic Potential, US EPA Office of Pesticide Programs, Washington, US, 1996.

- Benomyl, Environmental Health Criteria No 148, World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland, 1993.