Benjamin Morrell

| Benjamin Morrell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

July 5, 1795 Rye, Westchester County, New York[1] |

| Died |

1839 (aged 43–44) Portuguese Mozambique[1] |

| Occupation | Sea captain |

| Spouse(s) | Abby Jane, née Wood |

| Children | Son, William Morrell |

| Parents | Benjamin Morrell Sr, mother's name unknown |

Benjamin Morrell (July 5, 1795 – 1839) was an American sealing captain and explorer who between 1823 and 1831 made a series of voyages, mainly to the Southern Ocean and the Pacific Islands, which are recorded in a colourful memoir A Narrative of Four Voyages. Morrell's reputation among his peers was for untruth and fantasy, and claims in his partly ghost-written account, especially those relating to his Antarctic experiences, have been disputed by geographers and historians.

Morrell had an eventful early career, running away to sea at the age of 16 and being twice captured and imprisoned by the British during the War of 1812. He subsequently sailed before the mast for several years before being appointed as chief mate, and later as captain, of the New York sealer Wasp. In 1823 he took Wasp for an extended voyage into subantarctic waters, and it was from this first voyage of a sequence of four that much of the controversy surrounding his reputation developed. Many of his claims—the first landing on Bouvet Island, a Weddell Sea penetration to 70°S, an extremely rapid passage of 3,500 nautical miles (6,500 km) at improbably high latitudes, and the discovery of a coastline he called New South Greenland—have been doubted or proved false. His subsequent three voyages, in different ships, were less contentious, although his descriptions of various incidents have been dismissed as fanciful or absurd.[2] His unreliability is also aggravated by his acknowledged habit of working the experiences of others into his narratives.

Although he has been a "stumbling-block to geographers,"[3] Morrell has been defended by writers and historians who, while deploring his style, have found explanations for his dubious claims and have accepted his basic honesty. His contemporaries were less generous to him; his reputation for untruth hampered his attempts to continue his career after the publication of his book, and he found it increasingly difficult to obtain employment. He is believed to have died in 1839, of a fever contracted in Mozambique while on the way back to the Pacific.

Early life and career

Morrell was born at Rye, in Westchester County, New York, on July 5, 1795. He grew up in Stonington, Connecticut, where his father, also named Benjamin, was employed as a shipbuilder.[1] Morrell, after minimal schooling, ran away to sea at the age of 12 "without taking leave of any member of my family, or intimating my purpose to a single soul".[4] During the War of 1812, which broke out while he was at sea, he was twice captured by the British; on his first voyage his ship, carrying a cargo of flour, was intercepted off St John's, Newfoundland, and Morrell was detained for eight months. His second voyage landed him in Dartmoor prison, England, for two years.[2] After his release Morrell continued his seafaring career, sailing before the mast as an ordinary seaman since his lack of education prevented him advancing to officer rank.[1] A sympathetic captain, Josiah Macy, taught him what he needed to know to qualify as an officer,[5] and in 1821 he was appointed chief mate on the sealer Wasp, under Captain Robert Johnson.[2]

Wasp was bound for the South Shetland Islands, which had been discovered three years earlier by the British Captain William Smith.[6] Morrell, who had evidently heard stories of these islands, was keen to go there.[2] On the ensuing voyage he was involved in a series of "remarkable adventures"[7] which included a narrow escape from drowning, then being lost at sea in a small boat during a gale that swept him 50 nautical miles (58 mi; 93 km) from the ship, and leading efforts to extricate Wasp when she became trapped in the ice.[7] On the day following his return to New York, Morrell was appointed captain of Wasp, while Johnson took over the schooner Henry.[7] The two ships were jointly commissioned to return to the South Seas for sealing, trading and exploration, and "to ascertain the practicality, under favourable circumstances, of penetrating to the South Pole."[8]

Four voyages

First voyage: South Seas and Pacific Ocean

Wasp and Henry sailed from New York on June 21, 1822, and remained together as far as the Falkland Islands. They then separated, Wasp travelling east in search of sealing grounds. Morrell's account of the next few months of the voyage, in Antarctic and subantarctic waters, is controversial. His claims of distances, latitudes and discoveries have been challenged as inaccurate or impossible, giving substance to his reputation among his contemporaries for untruth, and leading to much criticism by later writers.[9]

Antarctic waters

Morrell's journal indicates that Wasp reached South Georgia on November 20, and then sailed eastwards towards the isolated Bouvet Island, which lies approximately midway between Southern Africa and the Antarctic continent and is known as the world's remotest island.[10] It had been discovered in 1739 by the French navigator Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier,[11] but his plotting of its position was inaccurate;[12][13] Captain James Cook, in 1772, had been unable to find it and had assumed its nonexistence.[12] It had not been seen again until 1808, when the British sealing captains James Lindsay and Thomas Hopper reached it and recorded its correct position, though they were unable to land.[11][14] Morrell, by his own account, found the island without difficulty—with "improbable ease", in the words of historian William Mills—[11] before landing and hunting seals there. In his subsequent lengthy description, Morrell does not mention the island's most obvious physical feature, its permanent ice cover.[15] This has caused some commentators to doubt whether he actually visited the island.[11][16]

After leaving Bouvet Island Wasp continued eastward, reaching the Kerguelen Islands on December 31 where she remained for 11 days. The voyage then evidently continued to the south and east until February 1, 1823, when Morrell records his position as 65°52'S, 118°27'E.[17] Here, Morrell says he took advantage of an eleven-knot breeze and turned the ship, to begin a passage westward.[17] Apart from one undated position at 69°11'S, 48°15'E, Morrell's journal is silent until February 23, when he records crossing the Greenwich (0°) meridian.[17] Historians have doubted whether such a long passage from 118°E, about 3,500 nautical miles (4,000 mi; 6,500 km), could have been made so quickly in ice-strewn waters and against the prevailing winds.[11][18] Although some writers, including former Royal Navy navigator Rupert Gould, have argued that Morrell's claims as to speed and distance are plausible,[19] Morrell's undated interim latitude was later shown to be well inside the Antarctic mainland territory of Enderby Land. Gould, writing in 1928 before the continental boundaries of this sector of Antarctica were known, based his support for Morrell on the premise that Enderby Land was an island with a sea channel south of it.[20] He writes: "If at some future date Enderby Land is found to form part of the Antarctic continent, Morrell's most inveterate champions will, perforce, have to throw up the sponge."[21]

According to Morrell, Wasp reached the South Sandwich Islands on February 28. His presence there is corroborated by his descriptions of the harbour on Thule Island, confirmed by the early 20th century expeditions.[22][23] In the next phase of the voyage Morrell records that he took Wasp southwards and, the sea being remarkably clear of ice, reached a latitude of 70°14'S before turning north on March 14 as fuel for the ship's stoves was running out.[17] This journey, if Morrell's account is true, made him the first American sea-captain to penetrate the Antarctic Circle.[1] He believed, he says, that but for this deficiency he could have "made a glorious advance directly to the south pole, or to 85° without the least doubt".[17] Some credence to his claimed southern latitude is provided by James Weddell's voyage on a similar track, a month earlier. Weddell, like Morrell, reported a sea largely clear of ice, reaching 74°15'S before retreating.[24] The words used by Weddell to express his belief that the South Pole lay in open water are replicated by Morrell, whose account was written nine years after the event. Thus it is suggested by geographer Paul Simpson-Housley that Morrell may have plagiarised Weddell's experiences,[23] since Weddell's account had been published in 1827.[24]

New South Greenland

Morrell next describes how on the day after turning north from his southernmost point, a large tract of land was sighted in the region of 67°52'N, 44°11'W. Morrell refers to this land as "New South Greenland",[25] and records that during the next few days Wasp explored more than 300 nautical miles (350 mi; 560 km) of coast. Morrell provided vivid descriptions of the land's features, with observations of its abundant wildlife.[25] No such land exists; other appearances of land at or near this bearing, reported during the 1842 expedition of Sir James Clark Ross, have likewise proved imaginary.[26] In 1917 the Scottish explorer William Speirs Bruce wrote that the existence of land in this area "should not be rejected until absolutely disproved."[27] By this time both Wilhelm Filchner and Ernest Shackleton, in their respective ice-bound ships, had drifted close to the plotted positions of New South Greenland and reported no sign of it.[28][29] The view has been posited that what Morrell saw was actually the eastern coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, some 400 nautical miles (460 mi; 740 km) further west from his sighting.[30] This would require a navigational error of at least 10°, and a complete revision of Morrell's timeline after leaving the South Sandwich Islands.[23][31] Assuming that Morrell did not invent the experience, a possible explanation is that he witnessed a superior mirage.[23]

Pacific and home

On March 19 Morrell "bade farewell to the cheerless shores of New South Greenland",[25] and sailed away from the Antarctic never to return. The remaining stages of the voyage are uncontroversial, involving a year-long cruise in the Pacific Ocean. This took Wasp to the Galápagos Islands and also to the Juan Fernández Islands where, a century earlier, the Scottish seaman Alexander Selkirk had been marooned, providing the inspiration for the Robinson Crusoe story.[32] Wasp returned to New York in May 1824.

Subsequent voyages

Second voyage: North and South Pacific

For his second voyage Morrell took charge of a new ship, Tartar, which sailed from New York on July 19, 1824 for the Pacific Ocean. In the next two years Tartar first explored the American coastline from the Straits of Magellan to Cape Blanco (now in Oregon).[33] He then sailed westward to the islands of Hawaii, known at that time as the Sandwich Islands, where Captain James Cook had met his death nearly 40 years earlier.[33] Thereafter Tartar returned to the American coast and tracked slowly southwards back to the Straits of Magellan.

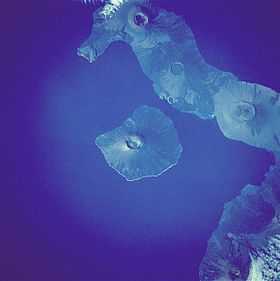

Among the events witnessed and recorded in Morrell's journal were the siege of Callao, the main port of Peru, by Simón Bolívar's liberators,[34][35] and a spectacular volcanic eruption on Fernandina Island in the Galápagos archipelago, which Tartar visited during February 1825. Fernandina, then known as Narborough Island,[36] exploded on February 14. In Morrell's words "The heavens appeared to be one blaze of fire, intermingling with millions of falling stars and meteors; while the flames shot upward from the peak of Narborough to the height of at least two thousand feet."[37] Morrell reports that the air temperature reached 123 °F (51 °C), and as Tartar approached the river of lava flowing into the sea, the water temperature rose to 150 °F (66 °C). Some of the crew collapsed in the heat.[37]

Morrell also records how a hunting trip ashore in California led to a skirmish with the locals which turned into a full-scale battle ending, he says, with seventeen natives dead and seven of Tartar's men wounded. Morrell claims that he was among the casualties, with an arrow in his thigh.[33] Of a visit to San Francisco Morrell writes: "The inhabitants are principally Mexicans and Spaniards who are very indolent and consequently very filthy."[33] After revisiting the Galapagos Islands and gathering a harvest of fur seal and terrapin,[38] Tartar began a slow journey home on October 13, 1825. As they left the Pacific Morrell claimed to have personally inspected and identified every danger existing along the American Pacific coast.[39] Tartar finally reached New York Harbour on May 8, 1826 with a main cargo of 6,000 fur seals. This haul did not please Morrell's employers, who had evidently expected rather more. "The reception I met from my owners was cold and repulsive", he wrote. "The Tartar did not return home laden with silver and gold, and therefore my toils and dangers counted for nothing".[40]

Third voyage: West African coast

In 1828 Morrell records that he was engaged by Messrs. Christian Berg & Co. to take command of the schooner Antarctic (named, he claims, in honour of his earlier Antarctic achievements).[41] Antarctic left New York on June 25, 1828, bound for Western Africa. During the following months Morrell carried out an extensive survey of the African coast between the Cape of Good Hope and Benguela, and led several short excursions inland. He was impressed by the commercial potential of this coast, recording that "many kinds of skins may be procured about here, including those of the leopard, fox, bullock, together with ostrich feathers and valuable minerals".[42] At Ichaboe Island he discovered huge deposits of guano, twenty-five feet thick, he reported.[43] In the face of such opportunity he records his belief that a $30,000 investment would produce in two years a profit "from ten to fifteen hundred per cent."[42]

During the voyage Morrell records several encounters with the slave trade, first at the Cape Verde Islands, then a centre for the trade due to their unique position equidistant from Europe, Africa and America.[44] He found the slaves' conditions wretched, but observes their passion for music which, he writes, "can alleviate even the pangs caused by the galling fetters of slavery".[45] Later in the voyage he witnessed what he describes as "horrid barbarity", including the spectacle of two women slaves in their death agonies as a result of floggings. After a lengthy soliloquy in his journal on the evils of slavery, he gives his conclusion that "the root, the source, the foundation of the evil is the ignorance and superstition of the poor negroes themselves".[46] From a trading standpoint the voyage had evidently proved prosperous beyond all expectation, so on June 8, 1829 Morrell decided to head for home. They arrived in New York on July 14.[46]

Fourth voyage: South Seas and Pacific Ocean

Antarctica left New York in September 1829 on the fourth of Morrell's voyages, bound for the Pacific. At her own insistence Morrell's wife accompanied him, and on her return prepared a memoir of her experiences (ghostwritten by Samuel Knapp),[5] her declared purpose being "the amelioration of the condition of the American seaman".[47] She was Morrell's second wife; his first, to whom he was married in 1819, had died along with her two children while Morrell was at sea in 1822–24.[48] He had then speedily married his 15-year-old cousin, Abbey Jane Wood.[1]

The first port of call was the Auckland Islands, south of New Zealand, where Morrell had hoped for a rich harvest of seal, but found the waters empty.[49] He sailed north for the Pacific islands where, during the following months, Antarctica was involved in violent skirmishes with the inhabitants of islands in the archipelago now known as Micronesia. One of these encounters developed into a major battle, described by Morrell as a "massacre".[50] His account has been dismissed as fanciful, while a more straightforward record was given by one of his injured crewmen.[51] This experience apparently did not deter Morrell from returning to these islands in order to exploit what he saw as their unrivalled commercial potential.[52] After subduing a further attack on the Antarctic from the natives of Nukuoro, he purchased an island from them, for cutlery, trinkets and other artefacts, including possibly the first metal tools they had seen.[53][54] His intention was to gather a harvest of biche-de-mer, an edible sea-slug common in these waters which evidently commanded a great price in the Chinese market.[55] Following a brief interval of peace, Morrell's stronghold on the island was attacked again, after which Morrell decided to abandon the enterprise, due to the "unappeasable vindictiveness and incessant hostilities" of the native population.[56]

On his return home, despite the lack of commercial success, Morrell remained optimistic about his future prospects in the Pacific. "I could, with only a modest share of patronage [...] open a new avenue of trade more lucrative than any that our country has ever yet enjoyed, and further, it would be in my power, and mine alone, to secure the monopoly for any term I pleased."[57] In the final paragraph of his account Morrell records that his wife's father, her aunt and her aunt's child had all died during his absence, as had one of Morrell's cousins and her husband.[58]

Later life, death and commemoration

After his return to New York, Morrell produced his Narrative of Four Voyages, a detailed account of his travels during the previous nine years, which was published in 1832. The book draws on Morrell's journals, but it is likely that much of the final text was ghost-written for him by a journalist, Samuel Wordsworth.[5][59] There is no record concerning the book's reception on publication, except the comment of explorer and journalist Jeremiah Reynolds to Morrell's fellow-explorer Nathaniel Palmer that the account had more poetry than truth.[16] However, a few years later Edgar Allan Poe drew heavily on the book (and other maritime narratives) when compiling his fictitious The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838).[60]

Morrell's seafaring career continued, first with a voyage to the Pacific in the schooner Mary Oakley. This ship was wrecked on the shores of Madagascar.[5] He then sought employment with the London-based shipping firm of Enderby Brothers, but Charles Enderby said that "he had heard so much of [Morrell] that he did not think fit to enter into any engagement with him."[3] A few years later Morrell applied for a place on a French expedition, led by Jules Dumont D'Urville, to the Weddell Sea, but again found himself unwanted.[61] He attempted to return to the Pacific in 1839, but contracted a fever in Mozambique and died there, aged 43 or 44.[5]

As a reminder of his brief Antarctic exploits, Morrell Island, at 59°27'S, 27°19'W, is the alternative name for Thule Island in the Southern Thule sub-group of the South Sandwich Islands.[62][63] During his Pacific travels Morrell encountered groups of islands that were not on his charts, treated them as new discoveries and named them after various New York acquaintances – Westervelt, Bergh, Livingstone, Skiddy. One was named "Young William Group" after Morrell's infant son. None of these names appear in modern maps, although the "Livingstone group" has been identified with Namonuito Atoll, and "Bergh's Group" with the Chuuk Islands.[64]

Assessment

Morrell has divided opinion among geographers, historians and commentators. His reputation among his contemporaries as the "biggest liar in the Pacific",[11][14] and the tone of his Four Voyages narrative, have deterred many from taking him seriously. Others, however, have considered that he has been done less than justice. "He may have been a braggart and a boaster", writes Rupert Gould, "but there is no evidence that he was a deliberate liar".[21] Indeed, Gould asserts, the book contains a great deal of accurate and valuable information; for example, Morrell's discovery of the guano deposits on Ichaboe Island, which laid the foundations of a flourishing industry.[65] His lack of a chronometer may have contributed to his frequent errors of position in the Antarctic leg of the first voyage;[5] at one point in this story he declares himself "destitute of the various nautical and mathematical instruments".[66] However, Gould rejects this explanation, since Morrell frequently refers to calculating his position "by observation", which would require a chronometer.[67] Hugh Robert Mill says that Morrell may have been vague as to dates and places, but "that he did sail [...] we cannot doubt, for he mentions the name of too many men still living at the date of publication to leave that matter in doubt".[61] He adds that a man may be ignorant and boastful, yet still do solid work,[2] a point echoed by historian W.J. Mills who points to the nuggets of truth among the mass of disinformation.[11]

The question of how much of Morrell's narrative is believable is complicated by his own admission, in the prefatory "advertisement" to his book, that he incorporated the experiences of others into his account.[68] Paul Simpson-Housley suggests that the details of his 1823 visit to Bouvet Island may have been taken from the records of an 1825 visit by Captain George Norris;[16] the similarities of Morrell's Weddell Sea narrative to that of James Weddell might be similarly explained.[23] The style of the book is described by Gould as "...simply dreadful—that of a 'spread-eagle' backwoods newspaper in Andrew Jackson's day".[65] Gould excuses this on the grounds that Morrell's contemporaries would have expected him to write in the style of a "free-born Yankee patriot" and would otherwise have regarded him with suspicion.[65] Hugh Robert Mill calls Morrell "intolerably vain, and as great a braggart as any hero of autobiographical romance", but finds the narrative itself "most entertaining".[2] None of these writers mentions that the book may have been ghost-written; Gould appears positively to discount this possibility.[69]

Contrarily, W.J. Mills finds the account "laboured, earnest and somewhat dull",[11] but uses this as evidence to support Morrell's basic integrity: "The whole style of the book [...] suggests that Morrell's narrative, at least in overall intent, is an honest one."[11] In regard to the Antarctic discoveries, which are Mills's particular concern, he points out that these are given no special emphasis. Morrell does not seem to regard the Antarctic expedition as particularly remarkable, and the discovery of "New South Greenland" is not claimed by Morrell himself but is credited to Captain Johnson in 1821.[11] Finally, Jeremiah Reynolds, despite his warnings to Palmer, included Morrell's Pacific discoveries in his report to Congress A Report of in relation to islands, reefs, and shoals in the Pacific Ocean.[70] This, says Simpson-Housley, was surely a compliment.[16]

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Dictionary of American Biography, p. 195

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 H.R.Mill, p. 104

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gould, p. 255

- ↑ Morrell, Introduction, pp. ix–xi

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 American National Biography (Vol. 15), p. 879

- ↑ H.R.Mill, pp. 94–95

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 H.R.Mill, p. 105

- ↑ Morrell, p. 30

- ↑ Gould, p. 255 and p. 258

- ↑ "Weather, wind and activity on Bouvetøya". Norwegian Polar Institute. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 11.9 Mills, pp. 434–35

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouver de Lozier, 1704–86". SouthPole.com. format- dmy. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ H.R.Mill, p. 47

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 McGonigal, p. 135

- ↑ H.R.Mill, pp. 106–107

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Simpson-Housley, p. 60

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Morrell, pp. 65–68

- ↑ H.R.Mill, pp. 107–08

- ↑ Gould, pp. 260–62

- ↑ See Gould, p. 257 and pp. 261–62.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Gould, p. 281

- ↑ Gould, p. 263

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 Simpson-Housley, pp. 57–59

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Exploration Through the Ages: James Weddell". The Mariners' Museum. Retrieved February 11.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Morrell, pp. 69–70

- ↑ Gould, pp. 272–74

- ↑ Bruce, in Scottish Geographical Magazine, June 1917, quoted in Gould, pp. 270–71

- ↑ "Wilhelm Filchner 1877–1957". South-pole.com. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- ↑ Shackleton. pp. 60–61

- ↑ H.R.Mill, pp.109–10

- ↑ Gould, pp. 276–82

- ↑ "Two extraordinary travellers: Alexander Selkirk – the real Robinson Crusoe?". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Morrell, pp. 203–15

- ↑ Rodriguez, p. 232

- ↑ Morrell, pp. 177–78

- ↑ "Turtles of the World". University of Amsterdam. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Kricher, p. 57

- ↑ Morrell uses the word "terrapin", presumably referring to the Galapagos tortoise. The terms were used interchangeably in Morrell's day; for example see Charles Darwin in Keynes, R.D. (ed.) (1979). The Beagle Record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-21822-1. Retrieved March 1, 2009., p. 312

- ↑ Morrell, p. 231

- ↑ Morrell, p. 251

- ↑ Morrell, pp. 253–54

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Morrell, p. 294

- ↑ "Ichaboe Island, Namibia". Animal Demography Unit, Namibia. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- ↑ "Slavery in Cape Verde". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved February 16.

- ↑ Morrell, p. 261

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Morrell, pp. 328–33

- ↑ "Two Hundred Years Before the Mast – Personal Narratives". University of Delaware. Retrieved February 12.

- ↑ Morrell does not name his first wife, nor the two children. See American National Biography, p. 879

- ↑ W.J.Mills, p. 39

- ↑ Morrell, pp. 410–14

- ↑ "Foreign Ships in Micronesia: Pohnpei". Micronesian Seminar. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ Morrell, p. 416

- ↑ Morrell, p. 440

- ↑ "A recently revealed tino aitu figure from Nukuoro Island". Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. Retrieved February 20, 2009. (Section 5)

- ↑ Baker, Samuel White (2008). "Eight Years' Wandering in Ceylon". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved February 26, 2009. Chapter 12, line 32

- ↑ Morrell, p. 452

- ↑ Morrell, p. 341

- ↑ Morrell, p. 492

- ↑ Introduction to Penguin Classics edition of The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket by E.A.Poe. Penguin Books. 1999. ISBN 978-0-14-043748-5. Retrieved February 27, 2009. (p. xvii)

- ↑ Ridgely, J.V. (June 1970). Poe Newsletter (Washington State University Press) III (1): 5–6 http://www.eapoe.org/pstudies/PS1960/P1970103.HTM

|url=missing title (help). Retrieved February 27, 2009. - ↑ 61.0 61.1 H R Mill, pp. 110–11

- ↑ "South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands". Geonames. 2008. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- ↑ Novatti, Ricardo (1963). "Pelagic Distribution of Birds in the Weddell Sea". Polarforsch (German Society of Polar Research) (33): 207–13. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ↑ "Foreign Ships in Micronesia: Chuuk". Micronesian Seminar. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 Gould, pp. 268–69

- ↑ Morrell, p. 67

- ↑ Gould, pp. 275–76

- ↑ Morrell, Preface ("advertisement") to A Narrative of Four Voyages

- ↑ Gould, p. 269

- ↑ House Document 105, 23rd Congress, Second Session 1835

Sources

Books and journals

- Baker, Samuel White (2008). "Eight Years' Wandering in Ceylon". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- general eds.: John A. Garraty .... (1999). Garraty, John A. and Mark C. Carnes, ed. American National Biography 15. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512794-3.

- Gould, Rupert T. (1929). Enigmas. London: Philip Allan & Co. ISBN 0-517-31081-3.

- Keynes, R.D. (ed.) (1979). The Beagle Record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-21822-1. Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- Kricher, John C. (2006). Galapagos: A natural history. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12633-3. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- McGonigal, David (2003). Antarctica. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-2980-8. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- Malone, Dumas, ed. (1934). Dictionary of American Biography VI. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Mill, Hugh Robert (1905). The Siege of the South Pole. London: Alston Rivers.

- Mills, William James (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara. ISBN 1-57607-422-6. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- Morrell, Benjamin (1832). A Narrative of Four Voyages...etc. New York: J & J Harper. Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- Novatti, Ricardo (1963). "Pelagic Distribution of Birds in the Weddell Sea". Polarforsch (German Society of Polar Research) (33): 207–13. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- Ridgely, J.V. (June 1970). "The Continuing Puzzle of Arthur Gordon Pym: Some Notes and Queries". Poe Newsletter (Washington State University Press) III (1): 5–6. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- Rodriguez, Jaime E (1998). The Independence of Spanish America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62673-6. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- Shackleton, Ernest (1983). South. London: Century Publishing. ISBN 0-7126-0111-2.

- Simpson-Housley, Paul (1992). Antarctica:Exploration, Perception and Metaphor. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-08225-9. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

Online

- "A recently revealed tino aitu figure from Nukuoro Island". Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- "Exploration Through the Ages: James Weddell". The Mariners' Museum. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- "Foreign Ships in Micronesia: Pohnpei". Micronesian Seminar. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- "Foreign Ships in Micronesia: Chuuk". Micronesian Seminar. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- "Ichaboe Island, Namibia". Animal Demography Unit, Namibia. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- Introduction to Penguin Classics edition of The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket by E.A.Poe. Penguin Books. 1999. ISBN 978-0-14-043748-5. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- "Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouver de Lozier, 1704–86". SouthPole.com. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- "Slavery in Cape Verde". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- "South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands". Geonames. 2008. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- "Turtles of the World". University of Amsterdam. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- "Two extraordinary travellers: Alexander Selkirk – the real Robinson Crusoe?". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- "Two Hundred Years Before the Mast – Personal Narratives". University of Delaware. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- "Weather, wind and activity on Bouvetøya". Norwegian Polar Institute. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- "Wilhelm Filchner 1877–1957". South-pole.com. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

|