Benjamin Franklin Tilley

| Benjamin Franklin Tilley | |

|---|---|

Benjamin Franklin Tilley | |

| Born |

March 29, 1848 Bristol, Rhode Island |

| Died |

March 18, 1907 (aged 58) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/branch | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1863–1907 |

| Rank | Rear Admiral |

| Commands held |

USS Bancroft USS Newport USS Vicksburg USS Abarenda USS Iowa Commandant of U.S. Naval Station Tutuila Commandant of League Island Naval Yard |

| Other work | Acting-Governor of American Samoa |

Benjamin Franklin Tilley (March 29, 1848 – March 18, 1907), often known as B. F. Tilley, was a career officer in the United States Navy who served from the end of the American Civil War through the Spanish–American War. He is best remembered as the first Acting-Governor of American Samoa, as well as the territory's first Naval governor.[1]

Tilley entered the United States Naval Academy during the height of the Civil War. Graduating after the conflict, he gradually rose through the ranks. As a lieutenant, he participated in the United States military's crackdown against workers in the wake of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. During the 1891 Chilean Civil War, Tilley and a small contingent of sailors and marines defended the American consulate in Santiago, Chile. As a commander during the Spanish-American War, Tilley and his gunship, the USS Newport, successfully captured two Spanish Navy ships. After the war, Tilley was made the first acting-Governor of Tutuila and Manua (later called American Samoa) and set legal and administrative precedents for the new territory. Near the conclusion of his 41 years of service, he was promoted to rear admiral, but died shortly afterwards from pneumonia.

Early life and naval career

Benjamin Franklin Tilley was born March 29, 1848, the sixth of nine children, in Bristol, Rhode Island.[2] During the American Civil War, Tilley enrolled in the United States Naval Academy on September 22, 1863, at the age of 15.[3] The war forced the school to relocate from Annapolis, Maryland (then held by the Confederacy) to Newport, Rhode Island. In 1866 he graduated first in his class,[4] going on to serve as a midshipman first on board the USS Franklin, and then the USS Frolic. Tilley spent three years serving on board the Frolic, eventually being promoted to ensign. His next assignment was on board the USS Lancaster, where he was promoted twice: first to master in 1870 and then to lieutenant in 1871. From 1872 to 1875, Tilley served on board the USS Pensacola in the South Pacific. After the Pensacola, he served briefly on board the USS New Hampshire and then spent two years serving on the USS Hartford.[3]

Railroad strike of 1877

In July 1877, a violent railroad strike began in Martinsburg, West Virginia, sparking riots in other American cities such as Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. In response, President Rutherford B. Hayes authorized the use of the military to put down the rioting. During the crisis, Tilley was temporarily transferred to the USS Plymouth, sailing up the Potomac River to Washington, D.C. Military leaders feared rioters from Baltimore could travel to Washington to seize or damage vulnerable government targets. The troops defending Washington, including army, navy, and marines, were organized into a battalion of seven companies; Tilley was placed in command of Company C. The precautions proved to be unnecessary, as the expected wave of rioters never materialized following the military's quashing of the strikers in Baltimore. Within a short time, the riots in other cities were also quashed.[5]

| Midshipman - 1867 | |

|---|---|

| 1867–1868 | USS Franklin |

| 1868–1869 | USS Frolic |

| Ensign - 1868 | |

| 1869–1872 | USS Lancaster |

| Master - 1870 | |

| Lieutenant - 1871 | |

| 1873–1875 | USS Pensacola |

| 1875 | USS New Hampshire |

| 1875–1877 | USS Hartford |

| 1877 | USS Plymouth |

| 1877–1878 | USS Powhatan |

| 1879–1881 | United States Naval Academy |

| 1881 | USS Standish |

| 1882 | United States Naval Academy |

| 1882–1885 | USS Tennessee |

| 1885–1889 | United States Naval Academy |

| Lieutenant Commander - September 1887 | |

| 1889–1890 | Washington Navy Yard |

| 1890–1893 | USS San Francisco |

| 1893–1897 | United States Naval Academy |

| 1896 | USS Bancroft |

| Commander - September 1896 | |

| 1897 | Naval War College |

| 1897–1898 | USS Newport |

| 1898 | Naval Station Newport |

| 1898–1899 | USS Vicksburg |

| 1899–1901 |

USS Abarenda U.S. Naval Station Tutuila |

| Captain - October 1901 | |

| 1902–1905 | Mare Island Naval Shipyard |

| 1905–1907 | USS Iowa |

| 1907 | Philadelphia Naval Shipyard |

| Rear Admiral - February 24, 1907 | |

After the strike, Tilley was transferred to the flagship USS Powhatan, before requesting to take a six-month leave so that he could marry. On June 6, 1878, Tilley married Emily Edelin Williamson, the daughter of a Navy surgeon and left with her on an extended honeymoon in Europe.[6] On his return to duty, Tilley served in the United States Naval Academy and remained there, either in a classroom or on a training ship, until 1882. For the next three years, Tilley served on board the USS Tennessee.[3] In 1885, Tilley was promoted to lieutenant commander and returned to teach at the academy. During his tenure there, he was appointed head of two departments: first the Department of Astronomy, Navigation, and Surveying and then transferred to the Department of Mechanical Drawing. In September 1889, he moved to the Washington Naval Yard to teach ordnance.[7]

Chilean Civil War

.jpg)

Spanish–American War

On April 23, 1898, Spain declared war on the United States in response to American efforts to support Cuban independence. Tilley, still in command of the Newport, was in the Caribbean and in the heart of the conflict. Two days after the United States responded with its own declaration of war against Spain, on April 27, Tilley captured the Spanish Navy's sloop Paquete and schooner Pireno.[13] Tilley participated in the naval blockade of Santiago de Cuba, but missed the subsequent Battle of Santiago de Cuba as the Newport was refueling at Guantánamo Bay when fighting broke out. Toward the end of the war, Tilley was responsible for shelling the Cuban port of Manzanillo.[14] Over the months of fighting, Tilley and the Newport assisted in the capture of nine Spanish vessels. At the conclusion of the war, he was transferred to the Newport Naval Yard,[15] before being given the command of the USS Vicksburg in October.[16]

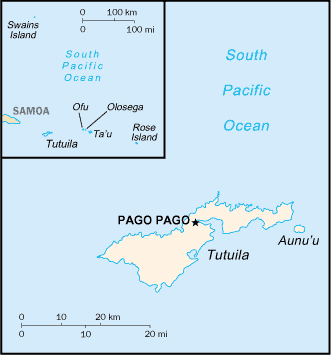

Commandant of U.S. Naval Station Tutuila

The United States first expressed interest in building a naval station at Pago Pago, Samoa in 1872 at the behest of Henry A. Peirce, the United States Minister to Hawaii. A treaty to that effect was written and submitted, but it was not approved by the United States Senate.[17] Six years later, on February 13, 1878, a separate treaty was ratified by the Senate that granted the Samoan government diplomatic recognition and reaffirmed permission to build a naval station in the country.[18] Although there were no further political obstacles, funding for the station was not allocated and only a small coaling station was built on the island. Construction of the naval station did not begin until twenty years later, in 1898, led by civilian contractors. In early 1899, Tilley was assigned the task of overseeing the station construction and becoming its first commandant. He was also put in command of a collier, the USS Abarenda, which would transport steel and coal to the construction site and to serve as the first station ship. After a long voyage, Tilley took on his new post on August 13, 1899.[19]

Even before Tilley arrived in Samoa, the political situation there was shifting. The Second Samoan Civil War had recently ended, leaving the nation without a functioning central government. The United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany had competing strategic or economic interests in the region. On June 10, 1899, the Western powers signed the Treaty of Berlin, which partitioned Samoa in two. The eastern part, with Tutuila as the largest island, was placed under the control of the United States. The larger and historically dominant western part was given to Germany. Under this treaty, the British government relinquished its claims over the region in exchange for certain concessions from Germany. News of this arrangement did not reach Tilley and the islands until December 6, 1899.[19]

After learning of the agreement, Tilley notified the local chiefs and asserted nominal United States control, but a formal decision on how the United States government would manage the territory had not yet been made. The construction of the naval base remained Tilley's primary responsibility, and he was dispatched to pick up additional supplies and coal at Auckland, New Zealand.[19] Less than a month after returning, on February 19, 1900, President William McKinley placed the territory under the control of the United States Navy. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Charles H. Allen named Tilley commandant of United States Naval Station Tutuila with a charter to "cultivate friendly relations with the natives".[19]

Acting Governor of Tutuila

As Acting Governor, Tilley's first acts were to impose a duty on imports to the territory, ban the sale of alcohol to the local population (but not Americans), and forbid the sale of Samoan lands to non-Samoans. On May 1, 1900, he proclaimed that the laws of the United States were in force in the territory, but that Samoan laws that did not conflict with US law would remain in effect. He partitioned the territory into three districts, along the historical divisions implicitly acknowledged in the deed of cession: the two governments on Tutuila and the third comprising the islands of Manu'a, which still did not regard themselves as part of the territory. Over the next year, Tilley regulated firearms, enforced mandatory registrations of births, deaths, and marriages, levied taxes, and made the sabbath a public holiday. For defense and police, Tilley created a small militia of native Samoans, called the Fita Fita Guard. The native volunteers in this force were trained at the naval station by a sergeant of the United States Marine Corps.[21]

During Tilley's administration problems arose because of conflicting Samoan and American laws. In one case, a native had caught and eaten a skipjack, a sacred fish which, under Samoan law, could only be eaten with the permission of a local chief. Traditional punishment decreed that the offender's house should be burned down, his crops uprooted, and he should be exiled from the territory. The native challenged his punishment under the American legal system however, resulting in the arrest of the chief responsible for ordering the destruction of his property. In a criminal proceeding on which Tilley sat as judge, the chief was sentenced to a year of house arrest and ordered to pay compensation for the destroyed property. There were similar issues with Samoan customs not blending well with the newly introduced American political divisions in the territory. For example, although the territory's three district governors had equal authority, they were of differing Samoan social status. This disparity made decision-making more difficult and caused social tensions.[22] Despite these problems, Tilley was well-considered by the locals. On December 18, 1900, the local chiefs sent a letter of congratulations on the re-election of President McKinley. In this letter, they said of Tilley "... you gave us a leader, a Governor, a High Chief, whom we have learned to love and respect".[21]

Tilley took leave in June 1901 to return to Washington, leaving E. J. Dorn in command. Dorn subsequently had medical issues and was replaced by J. L. Jayne in October. That month, an anonymous complaint was made to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Frank W. Hackett against Commandant Tilley, alleging immorality and drunkenness.[23] Almost simultaneously, Tilley was promoted to captain by President Theodore Roosevelt.[24] Tilley returned to Samoa on November 7, 1901 with his wife, and two days later was given a court martial. The trial lasted four days and only one witness was called for the prosecution. Ultimately, Tilley was acquitted. Despite this, Captain Uriel Sebree was appointed as commandant on November 27, 1901.[25] Tilley and his wife returned to the United States the following month.[23]

Sebree later remarked of his predecessor that he had "great ability, kindness, tact and sound common sense".[25] Unlike Sebree, who was concerned that he did not have a legal mandate to govern, Tilley was not shy about enacting legislation and being the de facto leader of the territory. Although the deed of cession recognized his authority and gave him the title of Acting Governor, as far as the United States government was concerned, he was officially responsible only for the naval station.[26] As the first naval governor, Tilley laid the groundwork for much of the future governance of the territory, which did not yet even have a formal name. The American Samoa government includes Tilley and the other pre-1905 station commandants in its list of territorial governors.[2]

Later career and death

Tilley's next assignment, in March 1902, was as captain of the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, California.[27] He remained in this post for three years before being assigned to the USS Iowa on January 11, 1905.[28] Two years later, on February 23, 1907, Tilley was made commandant of League Island Naval Yard in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was promoted to rear admiral the following day. Less than a month later, on March 18, 1907, Tilley died of pneumonia.[29] At the end of the year, Tilley was one of 322 men and women listed by the Washington Post as "foremost in their various callings" that had died in 1907.[30] Tilley was survived by one son and two daughters. His son, Benjamin Franklin Tilley, Jr., also entered the Navy and retired with the rank of lieutenant commander.[31]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Sorensen, Stan (2008-06-13). "Historical Notes, page 2". Tapuitea Volume III, No. 24. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Tilley". Government of American Samoa. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hamersly, Lewis Randolph (1898). The Records of Living Officers of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps (PDF) (6th ed.). New York: L. R. Hamersly and co. p. 106. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ↑ "Miscellaneous". The New York Times. 1866-07-21. p. 6.

- ↑ C., H. C. (January 1879). "The Naval Brigade and the Marine Battalions in the Labor Strikes of 1877". United Service 1 (1): pp. 115–130.

- ↑ "Society Weddings". Washington Post. 1878-06-06. p. 4.

- ↑ "Naval Academy Affairs". The Sun. 1885-09-29. p. Supplement 1.; "The Army and Navy". Washington Post. 1889-09-22. p. 12.; "The Army and Navy News". The New York Times. 1889-12-29. p. 16.

- ↑ "Nineteen Knots and Over". The New York Times. 1890-08-28. p. 1.

- ↑ "Santiago Capitulates". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1891-08-30. p. 1.

- ↑ "Notes from Annapolis". The New York Times. 1893-08-27. p. 16.

- ↑ "News from the Naval Academy". The New York Times. 1896-06-07. p. 21.

- ↑ "The United Service". The New York Times. 1896-10-21. p. 3.

- ↑ "The Panama's Valuation". Los Angeles Times. 1898-04-27. p. 3.

- ↑ Dyal, Donald H. (1996). Historical Dictionary of the Spanish American War. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 238–239. ISBN 0-313-28852-6.

- ↑ "The United Service". The New York Times. 1898-10-21. p. 4.

- ↑ Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. p. 58.

- ↑ Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 64–66.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 105–108.

- ↑ Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 157–158.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 125–128.

- ↑ Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 132–134.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 137–139.

- ↑ "To Be Captain in the Navy". The New York Times. 1901-10-08. p. 6.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Sebree, Uriel (1902-11-27). "Progress in American Samoa". The Independent 54 (2817): pp. 2811–2822.

- ↑ Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 150–151.

- ↑ "Assignment for Funston". Washington Post. 1902-03-18. p. 9.

- ↑ "The United Service". The New York Times. 1905-01-15. p. 5.

- ↑ "Death of Admiral Tilley". Washington Post. 1907-03-19. p. 3.

- ↑ "The Silent Reaper's Harvest of the Great". Washington Post. 1907-12-29. p. MS8.

- ↑ "Mrs. Emily Tilley Dies at Annapolis". Washington Post. 1931-04-22. p. 20.

References

- Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 498821.

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| First | Naval Governor of American Samoa February 17, 1900–November 27, 1901 |

Succeeded by Uriel Sebree |

| ||||||||||||||||