Bengali alphabet

| Bengali alphabet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Abugida |

| Languages | Bengali |

| Time period | 11th Century to the present[1] |

| Parent systems |

Proto-Sinaitic

|

| ISO 15924 | Beng, 325 |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Unicode alias | Bengali |

| Unicode range | U+0980–U+09FF |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Traditions

|

|

|

| Religion |

|

|

|

Literature History

Genres

Institutions Awards Writers

|

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Media

|

|

|

Monuments |

|

| Brāhmī |

|---|

| The Brahmic script and its descendants |

|

Northern Brahmic

|

|

Southern Brahmic

|

The Bengali alphabet (Bengali: বাংলা হরফ Bangla horof, Bengali: বাংলা লিপি and/or Bangla lipi) is the writing system for the Bengali language. The script with variations is shared by Maithili (also called Mithilakshar/Tirhutiya), Assamese and is the basis for the Meitei, Bishnupriya Manipuri, Kokborok, Garo and Mundari alphabets. All these languages are spoken in the eastern region of South Asia. Historically, the script has also been used to write the Sanskrit language in the same region. From a classificatory point of view, the Bengali script is an abugida, i.e. its vowel graphemes are mainly realized not as independent letters, but as diacritics attached to its consonant letters. It is written from left to right and lacks distinct letter cases. It is recognizable by a distinctive horizontal line running along the tops of the letters that links them together, a property it shares with two other popular Indian scripts: Devanagari (used for Hindi, Marathi and Nepali) and Gurumukhi (used for Punjabi). The Bengali script is, however, less blocky and presents a more sinuous shape.

Because of the large population of literate Bengali speakers, Bengali script is one of the more widely used writing systems in the world.

History

The Bengali script evolved from the Siddham, which belongs to the Brahmic family of scripts, along with the Devanagari and other written systems of the Indian subcontinent. In addition to differences in how the letters are pronounced in the different languages, there are some typographical differences between the version of the script used for Assamese and Bishnupriya Manipuri as well as Maithili languages, and that used for Bengali and other languages.

Illustration:

- The character ক্ষ (Assamese khyô, Bengali khio) is considered a separate letter in Assamese script (ক্ষ <khyô>) but considered a conjunct (orthographically ক্+ষ <kṣô>) in Bengali. In both languages, it functions as though it were orthographically খ্য <khy>.

- rô is represented as র in Bengali, ৰ in Assamese, and either of the two variants in Bishnupriya Manipuri and Maithili.

- Assamese script has an additional character sounding wô represented as ৱ not found in Bengali script.

The Bengali script was originally not associated with any particular language, but was often used in the eastern regions of Medieval India. It was standardized into the modern Bengali script by Ishwar Chandra under the reign of the British East India Company. The script was originally used to write Sanskrit. Epics of Hindu scripture, including the Mahabharata or Ramayana, were written Mithilakshar/Tirhuta script in this region. After the medieval period, the use of Sanskrit as the sole written language gave way to Pali, and eventually to the vernacular languages we know now as Maithili, Bengali, and Assamese.There is a rich legacy of Indian literature written in this script, which is still occasionally used to write Sanskrit today.

Standardization

In the Bengali script, clusters of consonants are represented by different and sometimes quite irregular forms; thus, learning to read is complicated by the sheer size of the full set of letters and letter combinations, numbering about 350. While efforts at standardizing the alphabet for the Bengali language continue in such notable centres as the Bangla Academies (unaffiliated) at Dhaka (Bangladesh) and Kolkata (West Bengal, India), it is still not quite uniform as yet, as many people continue to use various archaic forms of letters, resulting in concurrent forms for the same sounds. Among the various regional variations within this script, only the Assamese and Bengali variations exist today in the formalized system.

It seems likely that the standardization of the alphabet will be greatly influenced by the need to typeset it on computers. The large alphabet can be represented, with a great deal of ingenuity, within the ASCII character set, omitting certain irregular conjuncts. Work has been underway since around 2001 to develop Unicode fonts, and it seems likely that it will split into two variants, traditional and modern.

In this and other articles on Wikipedia dealing with the Bengali language, a Romanization scheme used by linguists specializing in Bengali phonology is included along with IPA transcription.

A recent effort by the government of West Bengal focused on simplifying Bengali orthography in primary school texts.

Description of Bengali glyphs

The glyphs of the Bengali script can be divided into vowel diacritics, consonant and vowel letters (including consonant conjuncts), modifiers, digits, and punctuation marks.

Vowels

The Bengali script has a total of 11 vowel graphemes, each of which is called a স্বরবর্ণ shôrobôrno "vowel letter". These shôrobôrnos represent six of the seven main vowel sounds of Bengali, along with two vowel diphthongs. All of these are used in both Bengali and Assamese, the two main languages using the script. There is no standard character in the script for the Bengali main vowel sound /æ/, and vowel length differences thought to be represented by different vowel graphemes (e.g., hrôshsho i vs. dirgho i) do not hold true for the spoken language. Also, the grapheme called ri does not really represent a vowel phoneme, rather the sound /ri/.

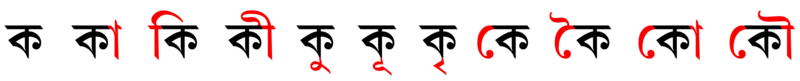

When a vowel sound occurs at the beginning of a syllable or when it follows another vowel, it is written using a distinct letter. But when a vowel sound follows a consonant (or a consonant cluster), it is written with a diacritic which, depending on the vowel, can appear above, below, before or after the consonant. The diacritic cannot appear without a consonant. A diacritic form is named by adding a "-kar" to the end of the name of the corresponding vowel letter (see table below).

An exception to the above system is the vowel /ɔ/. This has no diacritic form, but is considered inherent in every consonant letter. To specifically denote the absence of this inherent vowel [ɔ] following a consonant, a diacritic called the hôshonto (্) may be written underneath the consonant.

Although there are only two diphthongs in the inventory of the script, the Bengali sound system has in fact many diphthongs.[2] Most of these diphthongs are represented by juxtaposing the graphemes of their forming vowels, as in কেউ keu /keu/.

The table below shows the vowels present in the modern (i.e., since late nineteenth century) inventory of the Bengali alphabet, which has abandoned three historical vowels, rri, li, and lli, traditionally placed between ri and e.

| Full form | Name of full form | IPA transcription | Diacritic form, used with the consonant [kɔ] (ক) | Name of diacritic form | Transliteration | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| অ | shôro ô (shôre ô) "vowel ô" | /ɔ/ and /o/[3] | ক (none) | (none) | kô and ko | /kɔ/ and /ko/ |

| আ | shôro a (shôre a) "vowel a" | /a/ | কা | akar | ka | /ka/ |

| ই | hrôshsho i (hrôshsho i) "short i" | /i/ | কি | hrôshsho ikar (roshshikar) | ki | /ki/ |

| ঈ | dirgho i "long i" | /i/ | কী | dirgho ikar (dirghikar) | kee | /ki/ |

| উ | hrôshsho u (rôshsho u) "short u" | /u/ | কু | hrôshsho ukar (roshshukar) | ku | /ku/ |

| ঊ | dirgho u "long u" | /u/ | কূ | dirgho ukar (dirghukar) | koo | /ku/ |

| ঋ | ri | /ri/ | কৃ | rikar/rifôla | kri | /kri/ |

| এ | e | /e/ and /æ/ | কে | ekar | kê and ke | /ke/ and /kæ/ |

| ঐ | oi | /oj/ | কৈ | oikar | koi | /koj/ |

| ও | o | /o/ | কো | okar | ko | /ko/ |

| ঔ | ou | /ow/ | কৌ | oukar | kou | /kow/ |

Consonants

Consonant letters are called ব্যঞ্জনবর্ণ bênjonbôrno "consonant letter" in Bengali. The names of these letters are typically just the consonant sound plus the inherent vowel ô. Since the inherent vowel is assumed and not written, most letters' names look identical to the letter itself (e.g. the name of the letter ঘ is itself ঘ ghô). Some letters that have lost their distinctive pronunciation in Modern Bengali are called by a more elaborate name. For example, since the consonant phoneme /n/ can be written ন, ণ, or ঞ (depending on the spelling of the particular word), these letters are not simply called nô; instead, they are called দন্ত্য ন donto nô ("dental n"), মূর্ধন্য ণ murdhonno nô ("cerebral n"), and ঞীয়/ইঙ niô/ingô. Similarly, the phoneme /ʃ/ can be written শ talobbo shô ("palatal s"), ষ murdhonno shô ("cerebral s"), or স donto shô ("dental s"), depending on the word. Since the consonant ঙ /ŋ/ cannot occur at the beginning of a word in Bengali, its name is not ঙ ngô but উঙ ungô (pronounced by some as উম umô or উঁঅ ũô). Similarly, since semivowels ([j], [w], [e̯], [o̯]) cannot occur at the beginning of a Bengali word, the name for "semi-vowel e̯" য় is not অন্তঃস্থ য় ôntostho e̯ô but অন্তঃস্থ অ ôntostho ô.

In the earlier inventories of the Bengali alphabet, one can find a second bô (called ôntostho bô) following lô. This ôntostho bô originally represented a /v/ or /w/ sound, but later merged with the borgio bô in the Bengali language. The two bô's were represented with identically but occurred in two different places in the inventory. In the orthography of Bangladesh, only borgio bô is retained. The ôntostho bô continues to be used in the Indian state of West Bengal.

The table below presents the Bengali consonant letters in their traditional order.

| Letter | Name of consonant | Transliteration | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| ক | kô | k | /k/ |

| খ | khô | kh | /kʰ/ |

| গ | gô | g | /ɡ/ |

| ঘ | ghô | gh | /ɡʱ/ |

| ঙ | ungô, umô | ņ | /ŋ/ |

| চ | chô | ch | /tʃ/ |

| ছ | chhô | chh | /tʃʰ/ |

| জ | borgio jô (burgijjô) | j | /dʒ/ |

| ঝ | jhô | jh | /dʒʱ/ |

| ঞ | ingô, niô | n | /n/ |

| ট | ţô | ţ | /ʈ/ |

| ঠ | ţhô | ţh | /ʈʰ/ |

| ড | đô | đ | /ɖ/ |

| ঢ | đhô | đh | /ɖʱ/ |

| ণ | murdhonno nô (moddhennô) | n | /n/ |

| ত | tô | t | /t̪/ |

| থ | thô | th | /t̪ʰ/ |

| দ | dô | d | /d̪/ |

| ধ | dhô | dh | /d̪ʱ/ |

| ন | donto nô (dontennô) | n | /n/ |

| প | pô | p | /p/ |

| ফ | phô | ph | /pʰ/ |

| ব | bô (the so-called borgio bô) | b | /b/ |

| ভ | bhô | bh | /bʱ/ |

| ম | mô | m | /m/ |

| য | ôntostho jô (ontostejô) | j | /dʒ/ |

| র | (bôe bindu/shunno) rô | r | /ɾ/ |

| ল | lô | l | /l/ |

| শ | talobbo shô (taleboshshô) | sh and s | /ʃ/ / /s/ |

| ষ | murdhonno shô (muddhennoshshô) (peţ kaţa shô) | sh | /ʃ/ |

| স | donto shô (donteshshô) | sh and s | /ʃ/ / /s/ |

| হ | hô | h | /h/ |

| য় | ôntostho ô (ontosteô) | e and – | /e̯/ /- |

| ড় | đôe shunno/bindu ŗô | ŗ | /ɽ/ |

| ঢ় | đhôe shunno/bindu ŗô | ŗh | /ɽ/ |

Consonant conjuncts

Up to four consecutive consonants not separated by vowels can be orthographically represented as a ligature called a "consonant conjunct" (Bengali: যুক্তাক্ষর juktakkhor or যুক্তবর্ণ juktobôrno). Typically, the first consonant in the conjunct is shown above and/or to the left of the following consonants. Many consonants appear in an abbreviated or compressed form when serving as part of a conjunct. Others simply take exceptional forms in conjuncts, bearing little or no resemblance to the base character.

Often, consonant conjuncts are not actually pronounced as would be implied by the pronunciation of the individual components. For example, adding ল lô underneath শ shô in Bengali creates the conjunct শ্ল, which is not pronounced shlô but slô in Bengali. Many conjuncts represent Sanskrit sounds that were lost centuries before modern Bengali was ever spoken, as in জ্ঞ, which is a combination of জ jô and ঞ niô, but is not pronounced jnô. Instead, it is pronounced ggõ in Bengali. Thus, as conjuncts often represent (combinations of) sounds that cannot be easily understood from the components, the following descriptions are concerned only with the construction of the conjunct, and not the resulting pronunciation. Thus, a variant of the IAST romanization scheme is used instead of the phonemic romanization.

Fused forms

Some consonants fuse in such a way that one stroke of the first consonant also serves as a stroke of the next.

- The consonants can be placed on top of one another, sharing their vertical line: ক্ক kkô গ্ন gnô গ্ল glô ন্ন nnô প্ন pnô প্প ppô ল্ল llô etc.

- As the last member of a conjunct, ৱ wô and ব bô can hang on the vertical line under the preceding consonants, taking the shape of ব bô (here referred to as বফলা bôfôla): গ্ব gwô/gbô ণ্ব ṇwô,ṇbô দ্ব dwô/dbô ল্ব lwô/lbo শ্ব śwô/śbô.

- The consonants can also be placed side-by-side, sharing their vertical line: দ্দ ddô ন্দ ndô ব্দ bdô ব্জ bjô প্ট pṭô শ্চ ścô শ্ছ śchô etc.

Approximated forms

Some consonants are simply written closer to one another to indicate that they are in a conjunct together.

- As the last member of a conjunct, গ gô can appear unaltered, with the preceding consonant simply written closer to it: দ্গ dgô.

- As the last member of a conjunct, ৱ wô and ব bô can appear immediately to the right of the preceding consonant, taking the shape of ব bô (here referred to as বফলা bôfôla): ধ্ব dhwô/dhbô ব্ব bbô/bwô হ্ব hbô/hwô.

Compressed forms

Some consonants are compressed (and often simplified) when appearing as the first member of a conjunct.

- As the first member of a conjunct, the consonants ঙ ŋô চ cô ড ḍô ব bô and ৱ wô are often compressed and placed at the top-left of the following consonant, with little or no change to the basic shape: ঙ্ক্ষ ŋkṣô ঙ্খ ŋkhô ঙ্ঘ ŋghô ঙ্ম ŋmô চ্চ ccô চ্ছ cchô চ্ঞ cñô ড্ড ḍḍô ব্ব bbô/bwô ৱ্ব wbô/wwo.

- As the first member of a conjunct, ত tô is compressed and placed above the following consonant, with little or no change to the basic shape: ত্ন tnô ত্ম tmô ত্ব twô/tbô.

- As the first member of a conjunct, ম mô is compressed and simplified to a curved shape. It is placed above or to the top-left of the following consonant: ম্ন mnô ম্প mpô ম্ফ mfô ম্ব mbô/mwô ম্ভ mbhô ম্ম mmô ম্ল mlô.

- As the first member of a conjunct, ষ ṣô is compressed and simplified to an oval shape with a diagonal stroke through it. It is placed to the top-left of the following consonants: ষ্ক ṣkô ষ্ট ṣṭô ষ্ঠ ṣṭhô ষ্প ṣpô ষ্ফ ṣfô ষ্ম ṣmô.

- As the first member of a conjunct, স sô is compressed and simplified to a ribbon shape. It is placed above or to the top-left of the following consonant: স্ক skô স্খ skhô স্ট sṭô স্ত stô স্থ sthô স্ন snô স্প spô স্ফ sfô স্ব swô/sbô স্ম smô স্ল slô.

Abbreviated forms

Some consonants are abbreviated when appearing in conjuncts, losing part of their basic shape.

- As the first member of a conjunct, জ jô can lose its final downstroke: জ্জ jjô জ্ঞ jñô জ্ব jwô/jbô.

- As the first member of a conjunct, ঞ ñô can lose its bottom half: ঞ্চ ñcô ঞ্ছ ñchô ঞ্জ ñjô ঞ্ঝ ñjhô.

- As the last member of a conjunct, ঞ ñô can lose its left half (the এ part): জ্ঞ jñô.

- As the first member of a conjunct, ণ ṇô and প pô can lose their downstroke: ণ্ঠ ṇṭhô ণ্ড ṇḍô প্ত ptô প্স psô.

- As the first member of a conjunct, ত tô and ভ bhô can lose their final upward tail: ত্ত ttô ত্থ tthô ত্র trô ভ্র bhrô.

- As the last member of a conjunct, থ thô can lose its final upstroke, taking the form of হ hô instead (this form is called খণ্ড-থ khônḍo thô or "broken thô"(ঽ)) : ন্থ nthô স্থ sthô. An exception is ম্থ mthô (see on the compressed forms part)

- As the last member of a conjunct, ম mô can lose its initial downstroke: ক্ম kmô গ্ম gmô ঙ্ম ŋmô ট্ম ṭmô ণ্ম ṇmô ত্ম tmô দ্ম dmô ন্ম nmô ম্ম mmô শ্ম śmô ষ্ম ṣmô স্ম smô.

- As the last member of a conjunct, স sô can lose its top half: ক্স ksô ন্স nsô.

- As the last member of a conjuct ট ṭô, ড ḍô and ঢ ḍhô can lose their matra: প্ট pṭô ণ্ড ṇḍô ণ্ট ṇṭô ণ্ঢ ṇḍhô

- As the last member of a conjuct ড ḍô can change its shape: ণ্ড ṇḍô

Variant forms

Some consonants have forms that are used regularly, but only within conjuncts.

- As the first member of a conjunct, ঙ ŋô can appear as a loop and curl: ঙ্ক ŋkô ঙ্গ ŋgô.

- As the last member of a conjunct, the curled top of ধ dhô is replaced by a straight downstroke to the right, taking the form of ঝ jhô instead: গ্ধ gdhô দ্ধ ddhô ন্ধ ndhô ব্ধ bdhô.

- As the first member of a conjunct, র rô appears as a diagonal stroke (called রেফ ref) above the following member: র্ক rkô র্খ rkhô র্গ rgô র্ঘ rghô etc.

- As the last member of a conjunct, র rô appears as a wavy horizontal line (called রফলা rôfôla) under the previous member: খ্র khrô গ্র grô ঘ্র ghrô ব্র brô etc.

- In some fonts, certain conjuncts with রফলা rôfôla appear using the compressed (and often simplified) form of the previous consonant: জ্র jrô ট্র ṭrô ঠ্র ṭhrô ড্র ḍrô ম্র mrô স্র srô.

- In some fonts, certain conjuncts with রফলা rôfôla appear using the abbreviated form of the previous consonant: ক্র krô ত্র trô ভ্র bhrô

- As the last member of a conjunct, য yô appears as a wavy vertical line (called যফলা jôfôla) to the right of the previous member: ক্য kyô খ্য khyô গ্য gyô ঘ্য ghyô etc.

- In some fonts, certain conjuncts with যফলা jôfôla appear using special fused forms: দ্য dyô ন্য nyô শ্য śyô ষ্য ṣyô স্য syô হ্য hyô.

Exceptions

- When followed by র rô, ক kô takes on the abbreviated form of ত tô with the addition of a curl to the right: ক্র krô.

- When preceded by the abbreviated form of ঞ ñô, চ cô takes the shape of ব bô: ঞ্চ ñcô

- When preceded by another ট ṭô, ট ṭô is reduced to a leftward curl: ট্ট ṭṭô.

- When preceded by ষ ṣô, ণ ṇô appears as two loops to the right: ষ্ণ ṣṇô.

- As the first member of a conjunct, or when word-final and followed by no vowel, ত tô can appear as ৎ (called খণ্ড-ত khônḍo tô or "broken tô"): ৎস tsô ৎপ tpô ৎক tkô etc.

- When preceded by হ hô, ন nô appears as a curl to the right: হ্ন hnô.

- Certain combinations simply must be memorized: ক্ষ kṣô হ্ম hmô.

- When followed by ত tô, ক kô takes on the shape of ত্ত ttô with the addition of a curl to the right: ক্ত ktô.

Exceptional consonant-vowel combinations

When serving as a vowel sign, উ u, ঊ ū, and ঋ ṛ take on many exceptional forms.

- উ u

- When following গ gô or শ śô, it takes on a variant form resembling the final tail of ও o: গু gu শু śu.

- When following a ত tô that is already part of a conjunct with প pô, ন nô or স sô, it is fused with the ত tô to resemble ও o: ন্তু ntu স্তু stu প্তু ptu.

- When following র rô, and in many fonts also following the variant রফলা rôfôla, it appears as an upward curl to the right of the preceding consonant as opposed to a downward loop below: রু ru গ্রু gru ত্রু tru থ্রু thru দ্রু dru ধ্রু dhru ব্রু bru ভ্রু bhru শ্রু śru.

- When following হ hô, it appears as an extra curl: হু hu.

- ঊ ū

- When following র rô, and in many fonts also following the variant রফলা rôfôla, it appears as a downstroke to the right of the preceding consonant as opposed to a downward hook below: রূ rū গ্রূ grū থ্রূ thrū দ্রূ drū ধ্রূ dhrū ভ্রূ bhrū শ্রূ śrū.

- ঋ ṛ

- When following হ hô, it takes the variant shape of ঊ ū: হৃ hṛ.

Conjuncts of three consonants also exist, and follow the same rules as above. Examples include স sô + ত tô +র rô = স্ত্র strô, ম mô + প pô + র rô = ম্প্র mprô, ঙ ŋô + ক kô + ষ ṣô = ঙ্ক্ষ ŋkṣô, জ jô + জ jô + ৱ wô = জ্জ্ব jjwô, ক kô + ষ ṣô + ম mô = ক্ষ্ম kṣmô. Theoretically, four-consonant conjuncts can also be created, as in র rô + স sô + ট ṭô + র rô = র্স্ট্র rsṭrô, but these are not found in real words.

Modifiers and others

| Symbol with [kɔ] (ক) | Name | Function | Transliteration | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ক্ | hôshonto "final hôsh" | Suppresses the inherent vowel [ɔ] | k | /k/ |

| কৎ | khônđo tô "broken tô" | Final unaspirated dental [t̪] (ত) | kôt | /kɔt̪/ |

| কং | ônushshôr | Final velar nasal | kông | /kɔŋ/ |

| কঃ | bishôrgo |

|

- |

|

| কঁ | chôndrobindu "moon-dot" | Vowel nasalization | kôñ | /kɔ̃/ |

ঃ -h and ং -ng are also often used as abbreviation marks in Bengali, with ং -ng used when the next sound following the abbreviation would be a nasal sound, and ঃ -h otherwise. For example ডঃ ḍôh stands for ডক্টর ḍôkṭor "doctor" and নং nông stands for নম্বর nômbor "number". Some abbreviations have no marking at all, as in ঢাবি ḍhabi for ঢাকা বিশ্ববিদ্যালয় Ḍhaka Bishshobiddalôe "Dhaka University". The full stop can also be used when writing out English letters as initials, such as ই.ইউ. i iu "E.U.".

The jôphôla is sometimes used as a diacritic to indicate non-Bengali vowels of various kinds in transliterated foreign words. For example, the schwa is indicated by a jôphôla, the French u and the German umlaut ü as উ্য, the German umlaut ö as ও্য or এ্য, etc.

The apostrophe, known in Bengali as ঊর্ধ্বকমা urdhokôma "upper comma", is sometimes used to distinguish between homographs, as in পাটা paţa "plank" and পা'টা paţa "the leg". Sometimes a hyphen is used for the same purpose (as in পা-টা, an alternative of পা'টা).

Digits and numerals

The Bengali script has ten digits (graphemes or symbols indicating the numbers from 0 to 9), which are variants of Indian numerals (known as Arabic numerals in the West). Bengali digits have no horizontal headstroke or "matra".

| English digits | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bengali digits | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ |

| Bengali names of digits |

shunno | êk | dui | tin | char | pãch | chhôe | shat | aţ | nôe |

| শূন্য | এক | দুই | তিন | চার | পাঁচ | ছয় | সাত | আট | নয় | |

Numbers larger than 9 are written in Bengali using a positional base 10 numeral system (the decimal system), just as in English. A period or dot is used to denote the decimal separator, which separates the integral and the fractional parts of a decimal number. When writing large numbers with many digits, commas are used as delimiters to group digits, indicating the thousand (হাজার hajar), the hundred thousand or lakh (লাখ lakh or লক্ষ lokkho), and the ten million or hundred lakh or crore (কোটি koṭi or ক্রোড় kroṛ) units. In other words, going leftwards from the decimal separator, the first grouping consists of three digits, and the subsequent groupings always consist of 2 digits.

For example, the English number 17,557,345 will be written in traditional Bengali as ১,৭৫,৫৭,৩৪৫ (এক কোটি, পঁচাত্তর লাখ, সাতান্ন হাজার, তিন শ পঁয়তাল্লিশ êk koṭi põchattor lakh, shatanno hajar, tin sho põetallish, "one crore, seventy-five lakhs, fifty-seven thousand, three hundred forty-five").

The matra

Whereas in western scripts (Latin, Cyrillic, etc.) the letter-forms stand on an invisible baseline, the Bengali letter-forms hang from a visible horizontal left-to-right headstroke called মাত্রা matra (not to be confused with its Hindi cognate matra, which denotes the dependent forms of Hindi vowels). The presence and absence of this matra can be important. For example, the letter ত [tɔ] and the numeral ৩ "3" are distinguishable only by the presence or absence of the matra, as is the case between the consonant cluster ত্র [trɔ] and the independent vowel এ [e]. The letter-forms also employ the concepts of letter-width and letter-height (the vertical space between the visible matra and an invisible baseline).

Punctuation marks

Bengali punctuation marks, apart from the downstroke daŗi (|), the Bengali equivalent of a full stop, have been adopted from western scripts and their usage is similar. Commas, semicolons, colons, quotation marks, etc. are the same as in English. The concept of using capital letters is absent in the Bengali script, hence proper names are unmarked.

Characteristics of the Bengali text

Direction

Bengali text is written and read horizontally, from left to right.

Size

The consonant graphemes and the full form of vowel graphemes fit into an imaginary rectangle of uniform size (i.e. uniform width and height). The size of a consonant conjunct, regardless of its complexity, is deliberately maintained the same as that of a single consonant grapheme, so that diacritic vowel forms can be attached to it without any distortion.

Spacing

In a typical Bengali text, orthographic words, i.e., words as they are written, can be seen as being separated from each other by an even spacing. Graphemes within a word are also evenly spaced, but this spacing is much narrower than the spacing between words.

Punctuation marks

As discussed earlier, the Bengali punctuation marks are often the same as their English counterparts, both in form and function.

Characteristics of the orthographic word

In every Bengali orthographic word, one can find different kinds of graphemes and their combinations, and they are as follows:

- Independent form of vowel graphemes, which can be found at the beginning of a word or after another vowel sound.

- Consonant graphemes (or consonant conjuncts) with no diacritic vowel form attached to them. An inherent vowel (either /ɔ/ or /o/, depending on context[3]) is nevertheless assumed to be attached to them.

- Consonant graphemes (or consonant conjuncts) with a diacritic vowel form attached to them.

- Other modifier symbols indicating nasalization of vowels, suppression of the inherent vowel, etc.

The "matra"

The matra or the horizontal headstroke on each grapheme usually add up and often form a continuous single headstroke over the entire orthographic word, with different graphemes hanging down from it. This gives Bengali text a distinct look. Among other modern Indic scripts, Devanagari also has this characteristic, as does the Gurmukhi alphabet used to write Punjabi.

Inconsistencies

The following inconsistencies are inherent in the Bengali script and orthography. They often put additional burden on the person learning the script. The inconsistencies manifest themselves in various ways. Sometimes there are multiple different letters or symbols for the same sound (over-production). Sometimes a letter loses its original sound value. In other instances, the coverage of phonological information by the script is incomplete, inconsistent and/or ambiguous. Most of these inconsistencies can be attributed to the fact that the script was originally conceived to represent Sanskrit sounds.

Redundant graphemes for the vowel sounds [i] and [u]

The Bengali script has two symbols for the vowel sound [i] and two symbols for the vowel sound [u]. This redundancy stems from the time when this script was used to write Sanskrit, a language that had a short [i] and a long [iː], and a short [u] and a long [uː]. These letters are preserved in the Bengali script with their traditional names of hrôshsho i/u (lit. "short i/u") and dirgho i/u (lit. "long i/u") despite the fact that they are no longer pronounced differently in ordinary speech. These graphemes do serve an etymological function, however, in preserving the original Sanskrit spelling in tôtshomo Bengali words (i.e., words that were borrowed from Sanskrit).

The vowel grapheme ri

The grapheme called ri does not really represent a vowel phoneme in Bengali, rather the consonant-vowel combination /ri/. Nevertheless, it is included in the vowel section of the inventory of the Bengali script. This inconsistency is also a remnant from Sanskrit, where the grapheme represents a retroflex approximant, a sound considered a vowel in Sanskrit.

The vowel sound [æ]

Even though the near-open front unrounded vowel [æ] is one of the seven main vowel sounds in the standard Bengali language, no distinct vowel symbol has been allotted for it in the script, since there is no [æ] sound in Sanskrit, the primary written language when the script was conceived. As a result, this sound is orthographically realized by multiple means in modern Bengali orthography, usually using some combination of এ, অ, আ and the jôfôla (diacritic form of the consonant grapheme য ôntostho jô) as seen in the following examples:

- word-initially: এত [æt̪o] "so much", এ্যাকাডেমী [ækademi] "academy", অ্যামিবা [æmiba] "amoeba"

- word-medially and following a consonant: দেখা [d̪ækha] "to see", ব্যস্ত [bæst̪o] "busy", ব্যাকরণ [bækɔron] "grammar".

ত and ৎ

In native or tôdbhôbo Bengali words, syllable-final ত tô is pronounced /t̪/, as in নাতনি /nat̪ni/ "grand daughter", করাত /kɔrat̪/ "saw", etc.

ৎ (called খণ্ড-ত khônḍo tô "broken tô") is always used syllable-finally and always pronounced as /t̪/. It is predominantly found in loan words from Sanskrit such as ভবিষ্যৎ /bʱobiʃːɔt̪/ "future", সত্যজিৎ /ʃot̪ːod͡ʒit̪/ "Satyajit (a proper name)", etc. It is also found in some onomatopoeic words (such as থপাৎ /t̪ʰopat̪/ "sound of something heavy that fell", মড়াৎ /mɔɽat̪/ "sound of something breaking", etc.), as the first member of some consonant conjuncts (such as ৎস tsô, ৎপ tpô, ৎক tkô, etc.), and in some foreign loanwords (e.g. নাৎসি /nat̪si/ "Nazi", জুজুৎসু /d͡ʒud͡ʒut̪su/ "Jujitsu", etc.) which contain the same conjuncts.

This is an over-production inconsistency, where the sound /t̪/ is realized by both ত and ৎ. This creates confusion among inexperienced writers of Bengali. There is no simple way of telling which symbol should be used. Usually, the contexts where ৎ is used need to be memorized, as these are less frequent.

শ, ষ and স

Three graphemes—শ talobbo shô "palatal s", ষ murdhonno shô "cerebral s", and স donto shô "dental s"—are used to represent the voiceless palato-alveolar fricative [ʃ], as seen in their word-final pronunciations in ফিসফিস [pʰiʃpʰiʃ] "whisper", বিশ [biʃ] "twenty" and বিষ [biʃ] "poison". The grapheme স donto shô "dental s", however, does retain the voiceless alveolar fricative [s] sound when used as the first component in certain consonant conjuncts as in স্খলন [skʰɔlon] "fall", স্পন্দন [spɔndon] "beat", etc.

জ and য

There are two letters (জ and য) for the voiced postalveolar affricate [dʒ]. Compare জাল [dʒal] "net" and যাও [dʒao] "Go!".

ণ

What was once pronounced and written as a retroflex nasal ণ [ɳ] is now pronounced as an alveolar [n] (unless conjoined with another retroflex consonant such as ট, ঠ, ড and ঢ), although the spelling does not reflect this change.

Comparison

Romanization

The romanization of Bengali is the representation of the Bengali language in the Latin script. While different standards for romanization have been proposed for Bengali, these have not been adopted with the degree of uniformity seen in languages such as Japanese or Sanskrit.[4] Most standardized Bengali romanizations are adapted from standards proposed for Indic languages, and these models are compared below.

History

The Portuguese missionaries stationed in Bengal in the 16th century were the first people to employ the Latin alphabet in writing Bengali books, the most famous of which are the Crepar Xaxtrer Orth, Bhed and the Vocabolario em idioma Bengalla, e Portuguez dividido em duas partes, both written by Manuel da Assumpção. But the Portuguese-based romanization did not take root. In the late 18th century Augustin Aussant used a romanization scheme based on the French alphabet. At the same time, Nathaniel Brassey Halhed used a romanization scheme based on English for his Bengali grammar book. After Halhed, the renowned English philologist and oriental scholar Sir William Jones devised a romanization scheme for Bengali and for Indian languages in general, and published it in the Asiatick Researches journal in 1801.[5] This scheme came to be known as the "Jonesian System" of romanization, and served as a model for the next century and a half.

Transliteration vs transcription

The Romanization of a language written in a non-Roman script can be based on transliteration (orthographically accurate, i.e. the original spelling can be recovered) or transcription (phonetically accurate, i.e. the pronunciation can be reproduced). This distinction is important in Bengali as its orthography was adopted from Sanskrit, and ignores sound change processes of several millennia. To some degree, all writing systems differ from the way the language is pronounced, but this may be more extreme for languages like Bengali. For example, the three letters শ, ষ, and স had distinct pronunciations in Sanskrit, but over several centuries, the standard pronunciation of Bengali (usually modeled on the Nadia dialect), has lost these phonetic distinctions (all three are usually pronounced as IPA [ʃ]) while the spelling distinction nevertheless persists in orthography.

In written texts, it is easy to distinguish between homophones such as শাপ shap "curse" and সাপ shap "snake". Such a distinction could be particularly relevant in searching for the term in an encyclopedia, for example. However, the fact that the words sound identical means that they would be transcribed identically; thus, some important meaning distinctions cannot be rendered in a transcription model. Another issue with transcription systems is that cross-dialectal and cross-register differences are widespread, and thus the same word or lexeme may have many different transcriptions. Even simple words like মন "mind" may be pronounced "mon", "môn", or (in poetry) "mônô" (e.g. the Indian national anthem, Jana Gana Mana).

Often, different phonemes (meaningfully different sounds) are represented by the same symbol or grapheme. Thus, the vowel এ can represent both [e] (এল elo [elo] "came"), or [ɛ] (এক êk [ɛk] "one"). Occasionally, words written in the same way (homographs) may have different pronunciations for differing meanings: মত can mean "opinion" (pronounced môt), or "similar to" (môto). Thus, some important phonemic distinctions cannot be rendered in a transliteration model. In addition, when representing a Bengali word to allow speakers of other languages to pronounce it easily, it may be better to use a transcription, which does not include the silent letters and other idiosyncrasies (e.g. স্বাস্থ্য shastho, spelled <swāsthya>, or অজ্ঞান ôggên, spelled <ajñāna>) that make Bengali orthography so complicated.

Comparison of romanizations

Comparisons of standard romanization schemes for Bengali are given in the table below. Two standards are commonly used for transliteration of Indic languages including Bengali. Many standards (e.g. NLK / ISO), use diacritic marks and permit case markings for proper nouns. Newer forms (e.g. Harvard-Kyoto) are more suited for ASCII-derivative keyboards, and use upper- and lower-case letters contrastively and forgo normal standards for English capitalization.

- "NLK" stands for the diacritic-based letter-to-letter transliteration schemes, best represented by the National Library at Kolkata romanization or the ISO 15919, or IAST. This is the ISO standard, and it uses diacritic marks (e.g. ā) to reflect the additional characters and sounds of Bengali letters.

- ITRANS is an ASCII representation for Sanskrit; it is one-to-many, i.e. there may be more than one way of transliterating characters, which can make internet searching more complicated. ITRANS representations forgo capitalization norms of English so as to be able to represent the characters using a normal ASCII keyboard.

- "HK" stands for two other case-sensitive letter-to-letter transliteration schemes: Harvard-Kyoto and XIAST scheme. These are similar to the ITRANS scheme, and use only one form for each character.

- XHK or Extended Harvard-Kyoto (XHK) stands for the case-sensitive letter-to-letter Extended Harvard-Kyoto transliteration. This adds some specific characters for handling Bengali text to IAST.

- "Wiki" stands for a phonemic transcription-based romanization. It is a sound-preserving transcription based on what is perceived to be the standard pronunciation of the Bengali words, with no reference to how it is written in Bengali script. It uses diacritics often used by linguists specializing in Bengali (other than IPA), and is the transcription system used to represent Bengali sounds in Wikipedia articles.

Examples

The following table includes examples of Bengali words Romanized using the various systems mentioned above.

| In orthography | Meaning | NLK | XHK | ITRANS | HK | Wiki | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| মন | mind | mana | mana | mana | mana | mon | [mon] |

| সাপ | snake | sāpa | sApa | saapa | sApa | shap | [ʃap] |

| শাপ | curse | śāpa | zApa | shaapa | zApa | shap | [ʃap] |

| মত | opinion | mata | mata | mata | mata | môt | [mɔt̪] |

| মত | like | mata | mata | mata | mata | môto | [mɔt̪o] |

| তেল | oil | tēla | tela | tela | tela | tel | [t̪el] |

| গেল | went | gēla | gela | gela | gela | gêlo | [ɡɛlo] |

| জ্বর | fever | jvara | jvara | jvara | jvara | jôr | [dʒɔr] |

| স্বাস্থ্য | health | svāsthya | svAsthya | svaasthya | svAsthya | shastho | [ʃast̪ʰo] |

| বাংলাদেশ | Bangladesh | bāṃlādēśa | bAMlAdeza | baa.mlaadesha | bAMlAdeza | Bangladesh | [baŋlad̪eʃ] |

| ব্যঞ্জনধ্বনি | consonant | byañjanadhvani | byaJjanadhvani | bya~njanadhvani | byaJjanadhvani | bênjondhoni | [bɛndʒond̪ʱoni] |

| আত্মহত্যা | suicide | ātmahatyā | AtmahatyA | aatmahatyaa | AtmahatyA | attõhotta | [at̪ːõhot̪ːa] |

Romanization reference

The IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) transcription is provided in the rightmost column, representing the most common pronunciation of the glyph in Standard Colloquial Bengali, alongside the various romanizations described above.

|

|

|

Unicode

Bengali script was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 1991 with the release of version 1.0.

The Unicode block for Bengali is U+0980 ... U+09FF:

| Bengali[1] Unicode.org chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+098x | ঁ | ং | ঃ | অ | আ | ই | ঈ | উ | ঊ | ঋ | ঌ | এ | ||||

| U+099x | ঐ | ও | ঔ | ক | খ | গ | ঘ | ঙ | চ | ছ | জ | ঝ | ঞ | ট | ||

| U+09Ax | ঠ | ড | ঢ | ণ | ত | থ | দ | ধ | ন | প | ফ | ব | ভ | ম | য | |

| U+09Bx | র | ল | শ | ষ | স | হ | ় | ঽ | া | ি | ||||||

| U+09Cx | ী | ু | ূ | ৃ | ৄ | ে | ৈ | ো | ৌ | ্ | ৎ | |||||

| U+09Dx | ৗ | ড় | ঢ় | য় | ||||||||||||

| U+09Ex | ৠ | ৡ | ৢ | ৣ | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ | ||

| U+09Fx | ৰ | ৱ | ৲ | ৳ | ৴ | ৵ | ৶ | ৷ | ৸ | ৹ | ৺ | ৻ | ||||

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

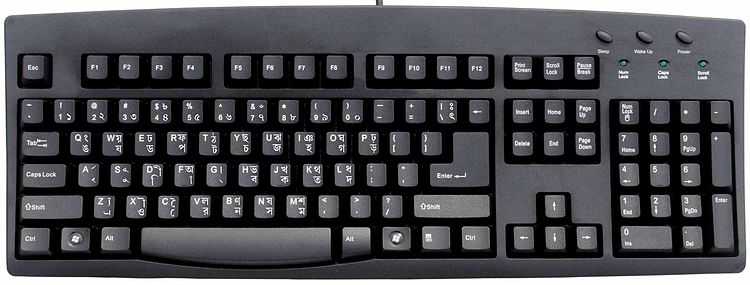

Bengali keyboard layouts

Avro Phonetic Keyboard

This keyboard is an integral part of an open source initiative, Avro Keyboard, by Omicron Lab

Bijoy keyboard layout

The Bijoy keyboard layout was commercialized by Mostafa Jabbar as part of the Bengali software package Bijoy Ekushe.

Inscript keyboard layout

The InScript keyboard layout was designed by the Indian government to standardize the inputting of Indic scripts.

Probhat keyboard layout

People used to typing Romanized forms of Bengali will find it easier to use a more phonetic layout such as the Probhat layout shown below, which is one of several Bengali input methods available.

Grapheme frequency

According to Bengali linguist Munier Chowdhury, the following 9 graphemes are the most frequent in Bengali texts:[6]

| Grapheme | Percentage |

|---|---|

| আ | 11.32 |

| এ | 8.96 |

| র | 7.01 |

| অ | 6.63 |

| ব | 4.44 |

| ক | 4.15 |

| ল | 4.14 |

| ত | 3.83 |

| ম | 2.78 |

Collating sequence

There is yet to be a uniform standard collating sequence (sorting order of graphemes to be used in dictionaries, indices, computer sorting programs, etc.) of Bengali graphemes. Experts in both India and Bangladesh are currently working towards a common solution for this problem.

Sample texts

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Bengali in Bengali alphabet

- ধারা ১: সমস্ত মানুষ স্বাধীনভাবে সমান মর্যাদা এবং অধিকার নিয়ে জন্মগ্রহণ করে। তাঁদের বিবেক এবং বুদ্ধি আছে; সুতরাং সকলেরই একে অপরের প্রতি ভ্রাতৃত্বসুলভ মনোভাব নিয়ে আচরণ করা উচিত।

Bengali in Romanization

- Dhara êk: Shômosto manush shadhinbhabe shôman môrjada ebong odhikar nie jônmogrohon kôre. Tãder bibek ebong buddhi achhe; shutorang shôkoleri êke ôporer proti bhrattrittoshulôbh monobhab nie achoron kôra uchit.

Bengali in IPA

- d̪ʱara æk ʃɔmost̪o manuʃ ʃad̪ʱinbʱabe ʃɔman mɔrdʒad̪a eboŋ od̪ʱikar nie dʒɔnmoɡrohon kɔre. t̪ãd̪er bibek eboŋ bud̪ʱːi atʃʰe; ʃut̪oraŋ ʃɔkoleri æke ɔporer prot̪i bʱrat̪ːrit̪ːoʃulɔbʱ monobʱab nie atʃoron kɔra utʃit̪.

Gloss

- Clause 1: All human free-manner-in equal dignity and right taken birth-take do. Their reason and intelligence exist; therefore everyone-indeed one another's towards brotherhood-ly attitude taken conduct do should.

Translation

- Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience. Therefore, they should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Amar Shonar Bangla

The following is a sample text of script, from the song Amar Shonar Bangla (আমার সোনার বাংলা) written by Rabindranath Tagore (রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর Robindronath Ṭhakur). The song was later adopted as the National anthem of Bangladesh.

| Bangla (Bengali) script | Romanization | Literal translation |

|---|---|---|

| মা, তোর মুখের বাণী

আমার কানে লাগে সুধার মতো- মা তোর বদন খানি মলিন হলে আমি নয়ন ও মায় আমি নয়ন জলে ভাসি সোনার বাংলা, আমি তোমায় ভালবাসি |

Ma, tor mukher bani |

Oh mother mine, words from your lips |

Jana Gana Mana

The following is a sample text of script, from the song Jana Gana Mana (জন গণ মন Jôno Gôno Mono). The selection is a Bengali song, written in Shadhubhasha (সাধুভাষা) style. The song was later adopted as the national anthem of India. It was written by Rabindranath Tagore (রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর Robindronath Ṭhakur) who is acknowledged as the single most important and defining figure of Bengali literature.

জনগণমন-অধিনায়ক জয় হে ভারতভাগ্যবিধাতা!

পঞ্জাব সিন্ধু গুজরাট মরাঠা দ্রাবিড় উৎকল বঙ্গ

বিন্ধ্য হিমাচল যমুনা গঙ্গা উচ্ছলজলধিতরঙ্গ

তব শুভ নামে জাগে, তব শুভ আশিষ মাগে,

গাহে তব জয়গাথা।

জনগণমঙ্গলদায়ক জয় হে ভারতভাগ্যবিধাতা!

জয় হে, জয় হে, জয় হে, জয় জয় জয় জয় হে।।

In Romanization:

Jônogônomono-odhinaeoko jôeô he Bharotobhaggobidhata!

Pônjabo Shindhu Gujoraţo Môraţha Drabiŗo Utkôlo Bônggo,

Bindho Himachôlo Jomuna Gôngga Uchchhôlojôlodhitoronggo,

Tôbo shubho name jage, tôbo shubho ashish mage,

Gahe tôbo jôeogatha.

Jônogônomonggolodaeoko jôeô he Bharotobhaggobidhata!

Jôeo he, jôeo he, jôeo he, jôeo jôeo jôeo, jôeo he!

In English translation:

Thou art the ruler of the minds of all people,

Dispenser of India's destiny.

Thy name rouses the hearts of Punjab, Sindh, Gujarat and Maratha,

Of the Dravida and Odisha and Bengal;

It echoes in the hills of the Vindhyas and Himalayas,

mingles in the music of Yamuna and Ganga and is

chanted by the waves of the Indian Ocean.

They pray for thy blessings and sing thy praise.

The saving of all people waits in thy hand,

Thou dispenser of India's destiny.

Victory, victory, victory to thee.

See also

- Bengali Braille

- Robert B. Wray movable type for Bengali (1778)

Footnotes and references

- ↑ Ancient Scripts

- ↑ Different Bengali linguists give different numbers of Bengali diphthongs in their works depending on methodology, e.g. 25 (Chatterji 1939: 40), 31 (Hai 1964), 45 (Ashraf and Ashraf 1966: 49), 28 (Kostic and Das 1972:6-7) and 17 (Sarkar 1987).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The natural pronunciation of the grapheme অ, whether in its independent (visible) form or in its "inherent" (invisible) form in a consonant grapheme, is /ɔ/. But its pronunciation changes to /o/ in the following contexts:

- অ is in the first syllable and there is a ই /i/ or উ /u/ in the next syllable, as in অতি oti "much" /ot̪i/, বলছি bolcchi "(I am) speaking" /ˈboltʃʰi/

- if the অ is the inherent vowel in a word-initial consonant cluster ending in rôfôla "rô ending" /r/, as in প্রথম prothom "first" /prot̪ʰom/

- if the next consonant cluster contains a jôfôla "jô ending", as in অন্য onno "other" /onːo/, জন্য jonno "for" /dʒonːo/

- ↑ In Japanese there exists some debate as to whether to accent certain distinctions, such as Tōhoku vs Tohoku. Sanskrit is well standardized, because the speaking community is relatively small, and sound change is not a large concern

- ↑ Jones 1801

- ↑ See Chowdhury 1963

Bibliography

- Ashraf, Syed Ali; Ashraf, Asia (1966), "Bengali Diphthongs", in Dil A. S., Shahidullah Presentation Volume, Lahore: Linguistic Research Group of Pakistan, pp. 47–52

- Chatterji, Suniti Kumar (1939), Vasha-prakash Bangala Vyakaran (A Grammar of the Bengali Language), Calcutta: University of Calcutta

- Chowdhury, Munier (1963), "Shahitto, shônkhatôtto o bhashatôtto (Literature, statistics and linguistics)", Bangla Academy Potrika (Dhaka) 6 (4): 65–76

- Kostic, Djordje; Das, Rhea S. (1972), A Short Outline of Bengali Phonetics, Calcutta: Statistical Publishing Company

- Hai, Muhammad Abdul (1964), Dhvani Vijnan O Bangla Dhvani-tattwa (Phonetics and Bengali Phonology), Dhaka: Bangla Academy

- Jones, William (1801), "Orthography of Asiatick Words in Roman Letters", Asiatick Researches (Calcutta: Asiatick Society)

- Sarkar, Pabitra (1987), "Bangla Dishôrodhoni (Bengali Diphthongs)", Bhasha (Calcutta) 4–5: 10–12

External links

- digital encoding and rendering

- Free Unicode Compliant Bangla Typing Software

- Ekushey Free Unicode Bangla Computing Solutions

- Free Bangla Unicode Fonts

- Ankur – Supporting Bangla (Bengali) on GNU/Linux

- Open source Bangla Transliteration Library

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||