Bendigo

| Bendigo Victoria | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

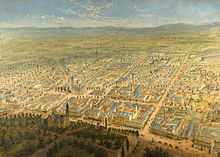

View of central Bendigo and eastern suburbs from Camp Hill | |||||||

Bendigo | |||||||

| Coordinates | 36°45′0″S 144°16′0″E / 36.75000°S 144.26667°ECoordinates: 36°45′0″S 144°16′0″E / 36.75000°S 144.26667°E | ||||||

| Population | 82,794 (2011)[1] (20th) | ||||||

| • Density | 567.1/km2 (1,469/sq mi) | ||||||

| Established | 1851 | ||||||

| Postcode(s) | 3550 | ||||||

| Elevation | 225 m (738 ft) | ||||||

| Area | 146 km2 (56.4 sq mi)[2] (UCL ABS 2011) | ||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10) | ||||||

| • Summer (DST) | AEST (UTC+11) | ||||||

| Location | 150 km (93 mi) NW of Melbourne | ||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Greater Bendigo | ||||||

| County | Bendigo | ||||||

| State electorate(s) | |||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Division of Bendigo | ||||||

| |||||||

Bendigo /ˈbɛndɨɡoʊ/ is a major regional city in the state of Victoria, Australia, located very close to the geographical centre of the state[3] and approximately 150 kilometres (93 mi) north west of the state capital, Melbourne. Bendigo has an urban population of 82,794 making it the fourth largest inland city in Australia and fourth most populous city in the state. It is the administrative centre for the City of Greater Bendigo which encompasses both the urban area and outlying towns spanning an area of approximately 3,000 square kilometres (1,158 sq mi) and over 100,000 people.[4]

The discovery of gold in the soils of Bendigo during the 1850s made it one of the most significant Victorian era boomtowns in Australia. It is also notable for its Victorian architectural and heritage. The city took its name from the Bendigo Creek and its residents from the earliest days of the goldrush have been called "Bendigonians".[5][6][7]

Bendigo is the largest finance centre in Victoria outside of Melbourne as home to Australia's only provincially headquartered retail bank, the Bendigo Bank, and the Bendigo Stock Exchange (BSX).

Gold was first discovered in 1851 at Golden Square on Bendigo Creek and the Bendigo Valley was found to be a rich alluvial field where gold could easily be extracted. News of the finds intensified the Victorian gold rush bringing an influx of migrants to the city from around the world within a year and transforming it from a sheep station to a major settlement in the newly proclaimed Colony of Victoria. Once the alluvial gold had been mined out, mining companies were formed to exploit the rich underground quartz reef gold. Since 1851 about 25 million ounces of gold (777 tonnes)[8] have been extracted from Bendigo's goldmines, making it the highest producing goldfield in Australia in the 19th century and the largest gold mining economy in eastern Australia.

History

Toponymy

The current name of "Bendigo" dates to the Victorian Gold Rush as a shortened form of "Bendigo Creek", the name originally given to the goldfields in November 1851 and also the name of the first post office which opened on 1 July 1852.

The Bendigo Creek (a continuation of Picanniny Creek[9][10]) extended downstream to its junction with Back Creek (near where Lake Weeroona is today) which formed one of the borders of the squatting run known as Mount Alexander North (later renamed the Ravenswood Run).[11] The first printed reference to the name is in the Government Gazette 1848, page 410, in a description of The Mount Alexander North Run and that referred to the creek as "Bednego(sic) creek".[12] The second printed reference to the name "Bendigo Creek" was in letters published on 13 December 1851 that had been written on 9 December 1851 by journalist and gold-miner Henry Frencham, one letter headlined "Mount Alexander" published in The Argus (Melbourne),[13] and the other headlined "Bendigo Creek Diggings" published in the Geelong Advertiser.[14] (A third letter was published close to that date in the Melbourne Daily Mail.[15]) In his letters Frencham also used the pen-name of "Bendigo".

The Bendigo Creek was named after "Bendigo's Hut",[11] the hut of a shepherd with the nickname of "Bendigo" who had resided at the creek during the 1840s.[16] The shepherd was nicknamed after the Nottingham bare-knuckled boxing prize-fighter William Abednego Thompson, generally known as “Bendigo Thompson”.[17] It was reported that the shepherd, who was also the hut-keeper, was "some pugilistically inclined individual"[18] and "a fighting sailor".[19] The former sailor, who had run away from his vessel, had been working on the ship that Thomas Myers had come to Port Phillip aboard.[20] The shepherd/sailor was given the nickname of "Bendigo" by Thomas Myers, who from August 1844[21] to July 1849[22] had been overseer on the Mount Alexander North Run (later renamed the Ravenswood Run) that at that time had been owned by Benjamin Heape and Richard Grice. The story was verified in a letter from Richard Grice;[23] by Mrs. W. Lauder from conversations that she had with Thomas Myers in 1852;[20] and by the shepherd William Sandbach from converstaions that he had with fellow shepherd, James Liston, who had lived on the Ravenswood Run from 1841, in the time of Heape and Grice, to 1851 when gold was discovered at Bendigo Creek in the time of the subsequent owners, the Gibson brothers.[24] Richard Grice was to write in 1878 that the reason for the choice of the name of "Bendigo" was that "Tom (Myers), himself, was a bit of a dab with his fists, and great admirer of the boxer Bendigo."[25] It was reported that the shepherd with the nickname of "Bendigo" later "shot through to California when news of the gold rushes there reached Australia" in the late 1840s.[8]

The town which began to develop on the goldfield was at first known as "Bendigo",[26] a shortened form of "Bendigo Creek". "Bendigo", however, although a popular name, was not in the earliest days of the settlement an official name. The town was at first officially named as "Castleton", after the mining town of Castleton, Derbyshire in England, in a government notice dated 2 December 1852. This name, however, only lasted six weeks. In a second government notice, dated 18 January 1853, the name was changed to "Sandhurst" after the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.[8][17] (The name of the post office, however, was not changed to Sandhurst until 1 January 1854.[8][17]) The nickname of "Bendigo", however, always remained popular. This is demonstrated in the name of the local newspaper which, from its establishment in 1854 until today, has been known as the Bendigo Advertiser. It is also demonstrated in the term "Bendigonian", still used today for a resident of Bendigo, but also used for a resident of Bendigo during the time that Bendigo had the name of Sandhurst (1854-1891).[27]

After a plebiscite on 28 April 1891,[28] which had been called as a direct result of agitation to have the old name back,[29] the city was renamed on 4 May 1891[8] to the more popular original name of "Bendigo", although the name "Sandhurst" has a legacy and is still used by a number of organisations such as the Sandhurst Football Club. The Roman Catholic diocese based in Bendigo is named the Diocese of Sandhurst.

Indigenous background

The original inhabitants of Greater Bendigo area were the clans of the Dja Dja Wurrung people, also known as the Jaara people. They were regarded by other tribes as being a superior people, not only because of their rich hunting grounds but because from their area came a greenstone rock for their stone axes. Early Europeans described the Dja Dja Wrung as a strong, physically well-developed people and not belligerent. Nevertheless the early years of European settlement in the Mount Alexander area were bloodied by many clashes between intruder and dispossessed.

European settlement

Major Mitchell passed through the region in 1836. Following his discovery, the first squatters arrived in 1837 to establish vast sheep runs. The Bendigo Creek was part of the Mount Alexander North or Ravenswood sheep run.

Discovery of gold

Gold was found at Bendigo Creek in September 1851. According to the Bendigo Historical Society, it is generally agreed that gold was found at Bendigo Creek by two married women from the Mount Alexander North Run (later renamed the Ravenswood Run), Margaret Kennedy (nee McPhee[30]) and Julia Farrell, at "The Rocks" area of Bendigo Creek at Golden Square, near where today's Maple Street crosses the Bendigo Creek.[31] When Margaret Kennedy gave evidence before a Select Committee in September 1890 she said that she had found gold near "The Rocks" in early September 1851.[19] September 1851 was also mentioned in relation to the three other sets of serious contenders for the first finders of gold at Bendigo Creek on the Mount Alexander North Run: Stewart Gibson, one of the two brothers who owned or leased the Mount Alexander North Run in 1851, and Frederick Fenton, the then overseer and later owner (Fenton claimed that he and Gibson had been together when they found gold in a water-hole at the junction of Golden Gully with Bendigo Creek in September 1851 just before shearing commenced but decided at the time to keep it quiet); one or more of the shepherds living in the hut on the Mount Alexander North Run near the junction of Golden Gully with Bendigo Creek, James Graham (alias Ben Hall), Benjamin Bannister, and hut-keeper Christian Asquith, and/or a shepherd who visited them at the hut named William Henry Johnson (who found gold near "The Rocks"); and one or both of the husbands of the two women, John "Happy Jack" Kennedy, an overseer of the Mount Alexander North Run who had his hut on the Bullock Creek at what is today known as Lockwood South, and Patrick Peter Farrell, a cooper (who found gold near "The Rocks").[19][32] The date of September 1851 is also commemorated in a monument erected on the main highway at Golden Square in front of the Senior Citizens' Club.

In September 1890 a Select Committee of the Victorian Legislative Assembly sat to decide who was the first to discover gold at Bendigo. They stated that there were at least 12 claimants to being the first to find gold at Bendigo (they included Margaret Kennedy in this number, but not Julia Farrell who was deceased), as well as the journalist Henry Frencham[33] who claimed to have discovered gold at Bendigo Creek in November 1851. (Frencham had previously also claimed to have been the first to have discovered gold at Warrandyte in June 1851 when he, unsuccessfully, claimed the £200 reward for finding payable gold within 200 miles (320 km) of Melbourne;[34][35] and then he also claimed to be the first to have discovered gold at Ballarat [then also known as Yuille’s Diggings] "and make it known to the public" in September 1851.[36]) In the evidence that Margaret Kennedy gave before the Select Committe in September 1890 she said that she and Julia Farrell had been secretly panning for gold before Henry Frencham arrived, evidence that was substantiated by others. The committee found "that Henry Frencham's claim to be the discoverer of gold at Bendigo has not been sustained", but could not make a decision as to whom of the other at least 12 claimants had been first as "it would be most difficult, if not impossible, to decide that question now"..."at this distance of time from the eventful discovery of gold at Bendigo". They concluded that there was "no doubt that Mrs Kennedy and Mrs Farrell had obtained gold before Henry Frencham arrived on the Bendigo Creek", but that Frencham "was the first to report the discovery of payable gold at Bendigo to the Commissioner at Forest Creek (Castlemaine)". (An event Frencham dated to 1 December 1851,[37] a date which was, according to Frencham's own contemporaneous writings, after a number of diggers had already begun prospecting on the Bendigo goldfield.[13] A letter from Frencham was delivered on 1 December 1851 to Chief Commissioner Wright at Forest Creek (Castlemaine) asking for police protection at Bendigo Creek, a request that officially disclosed the new goldfield. Protection was granted and the Assistant Commissioner of Crown Lands for the Gold Districts of Buninyong and Mt Alexander, Captain Robert Wintle Home, arrived with three black troopers (native police) to set up camp at Bendigo Creek on 8 December.[38]) The committee also decided "that the first place at which gold was discovered on Bendigo was at what is now known as Golden Square, called by the station hands in 1851 'The Rocks', a point about 200 yards to the west of the junction of Golden Gully with the Bendigo Creek."[16][19][32][37][39][39][40][41][42] (The straight-line distance is nearer to 650 yards [600 metres].) In October 1893 the man who had proposed the Select Committee, who was also one of the men who had sat on the committee, gave an address in Bendigo in which he gave his opinion on the matter of who had first found gold at Bendigo. Alfred Shrapnell Bailes, Mayor of Bendigo and member of the Legislative Council of Victoria, said that "upon the whole, from evidence which, read with the stations books, can be fairly easily pieced together, it would seem that Asquith, Graham, Johnson and Bannister (the three shepherds residing at the hut on Bendigo Creek and their shepherd visitor Johnson), were the first to discover gold".[18]

The first persons to mine for gold at the Bendigo Creek were people associated with the Ravenswood Run. They included Patrick Peter and Julia Farrell, John and Margaret Kennedy and Margaret's children John Drane (aged 9) and Mary Kennedy (aged 2),[43][44][45][46] and the shepherds Christian Asquith, James Graham (alias Ben Hall) and Bannister. They were joined by other shepherds who had been employed elsewhere on the Ravenswood Run than at Bendigo Creek, including William Henry Johnson, James Lister, William Ross, Paddy O'Donnell and William Sandbach and his brother, Walter, who arrived at the Bendigo Creek in November 1851.[19][26][32] They were soon joined by miners from the Forest Creek (Castlemaine) diggings including the journalist Henry Frencham.

Henry Frencham, under the pen-name of "Bendigo",[37] was the first to publicly write anything about gold mining at Bendigo Creek, with three reports about the same event, a meeting of miners at Bendigo Creek on 8 and 9 December 1851, published respectively in the Daily News, Melbourne (date unknown)[15] and the 13 December 1851 editions of the Geelong Advertiser[14] and The Argus, Melbourne.[13] It was Frencham's words, published in The Argus of 13 December 1851 that were to begin the Bendigo Goldrush:

- "As regards the success of the diggers, it is tolerably certain the majority are doing well, and few making less than half an ounce per man per day."

Henry Frencham may not have been the first person to find gold at Bendigo but he was the first person to announce to the authorities (1 December 1851) and then the world (The Argus, 13 December 1851) the existence of the Bendigo goldfield. He was also the first person to deliver a quantity of payable gold from the Bendigo gold-field to the authorities when on 28 December 1851, three days after the 603 men, women and children then working the Bendigo goldfield had pooled their food resources for a combined Christmas dinner,[47] Frencham and his partner Robert Atkinson, with Trooper Synott as an escort, delivered 30 lbs of gold that they had mined to Assistant Commissioner Charles J.P. Lydiard at Forest Creek (Castlemaine), the first gold received from Bendigo.[48]

In 1890 William Sandbach was to reminisce about the earliest days of gold-mining on Bendigo Creek, stating that "I have written this for the interested, dwelling in the once Bendigo, but now famous city (Sandhurst - the name of Bendigo from 1854 to 1891)". He recalled saying in January 1852 to his fellow shepherd James Lister "Jim, I should not wonder but what this one of these days will be a big diggings". He also quoted what is the earliest known poem written about the Bendigo Goldfields that he had composed at that time:

- O, lift your eyes, ye sighing sons of men;

- The long-fled golden age returns again.

- See! youthful riches, with his yellow wand,

- Touching the hills and valleys through the land.[26]

1850s - 1860s: Gold rush boomtown

In late November 1851 some of the miners at Castlemaine (Forest Creek), having heard of the new discovery of gold, began to move to Bendigo Creek joining those from the Mount Alexander North (Ravenswood) Run who were already prospecting there.[31] The beginnings of this gold-mining was reported from the field by Henry Frencham, under the pen-name of "Bendigo",[13][37][49] who stated that the new field at Bendigo Creek, which was at first treated as if it were an extension of the Mount Alexander or Forest Creek (Castlemaine) rush,[8][47] was already about two weeks old on 8 December 1851. Frencham reported then about 250 miners on the field (not counting hut-keepers). On 13 December Henry Frencham's article in The Argus was published announcing to the world that gold was abundant in Bendigo. Just days later, in mid-December 1851 the rush to Bendigo had begun, with a correspondent from Castlemaine for the Geelong Advertiser reported on 16 December 1851 that "hundreds are on the wing thither (to Bendigo Creek)".[50]

By April 1852, Bendigo Creek was regarded as a goldfield in its own right. On 27 April a Court of Petty Sessions was established and a fortnight later Robert Petty Stewart was appointed as the resident police magistrate.[8]

By June 1852 "it is estimated that there were 40,000 diggers on the field - an extraordinary number bearing in mind that in February pre-goldrush Melbourne had a total population of only 23,000".[51]

Also by June 1852 a mail delivery service was established between Forest Creek (Castlemaine) and Bendigo Creek.[8] The first official post office opened on 1 July 1852 under the name of "Bendigo Creek". It was predated by the other goldfields post offices at Ballarat on 1 November 1851, at Forest Creek (Castlemaine) on 1 March 1852, and at Carisbrook on 1 May 1852. The post office was renamed from "Bendigo Creek" to "Sandhurst" on 1 January 1854 and then to "Bendigo" on 8 May 1891.[52]

Chinese people, in particular, were attracted to the Bendigo goldfields in great numbers, establishing a large Chinatown on a bountiful gold run to the north east of the city at Emu Point. Within ten years the Chinese miners and merchants made up 20% of the Bendigo population. While most of the Chinese gold miners returned home when the alluvial goldfields declined, a small population remained to form the Bendigo Chinese community which has continued to influence the city.[53] Other ethnic communities also developed including the Germans at Ironbark Gully and the Irish at St Killian's.[8]

In 1853 there was a massive protest march by surface miners against the amount of the 30s gold license fee and the frequency, monthly, with which it was collected. This protest, the Red Ribbon Agitation, was peaceful (unlike the later Eureka Stockade event in Ballarat) because of the ability of the miners' leaders and the young Scots police commissioner, Joseph Anderson Panton. Predating the 1853 protest, on the evenings of 8 and 9 December 1851, when the diggers had only been on the Bendigo goldfield for two weeks, meetings were held to object to a government proposal to double the monthly gold license fee to 60s or £3.[13] These were also peaceful meetings, as was a similar evening meeting at Forest Creek (Chewton, Castlemaine) on 8 December, and a larger day-time "Monster Meeting" at Forest Creek (Chewton, Castlemaine) on 15 December that was attended by representatives from Bendigo, and it was reported about 15,000 out of the 25,000 diggers at Forest Creek.[54] The number assembled for the second meeting in Bendigo on 9 December 1851 was reported to be "gold diggers assembled to a man, except those engaged in looking after the tents" numbering about 250. The names of men who were reported to have addressed the meeting were the political activist Captain John Harrison,[55] the zoologist and mining engineer Count William Blandowski, the reporter Henry Frencham, the shepherd William Sandbach, Mr Regan, Mr Moss, Mr McDonald, Mr McGrath, and Dr Russell. A third meeting was held at Bendigo Creek on 1 January 1852 after the Government Camp Commissioner, Captain Dane, arrived to inspect the goldfield. This meeting was about wanting to continue to pay the monthly gold license fee in gold "as hitherto had been the custom" rather than in cash as the government was now requiring. The men reported to have addressed this meeting were William Sandbach, a Mr Coombs, a Mr P. McKenzie and a Mr W. Gamms.[56]

Bendigo quickly grew from a “city of tents” to become a substantial city with great public buildings. The first hospital was built in 1853, the first town plan was developed by 1854, the municipality (then known as the Sandhurst Municipality) was incorporated on 24 April 1855. The Bendigo Building Society (today's Bendigo Bank) began in 1858 in an effort to improve conditions on the Bendigo Goldfields. The first town hall was commissioned in 1859. The municipality became a borough on 11 September 1863.

Bendigo was connected to Melbourne by telegraph in 1857 and it was from Bendigo (then known as Sandhurst) that the first message reporting the deaths of Burke and Wills was sent on 29 June 1861.[57] The Bendigo Benevolent Asylum, now known as the Anne Caudle Centre, was erected in 1860. Frequent Cobb & Co coaches ran to Melbourne until the railway reached Bendigo in 1862. With the opening of the railway line the township grew rapidly.

By the end of the first gold rush in the 1860s, the township had established flour mills, woollen mills, tanneries, quarries, foundries, eucalyptus oil production, food production industries and timber-cutting.

When the early discoveries of alluvial gold began to run out the goldfields soon changed from small operations to major mines with deep shafts to mine the quartz-based gold. Mining companies were formed and numerous pit mines were sunk to exploit the underground ores which are found in elongated saddle quartz reefs in corrugated sedimentary rock.

1870s - 1890s: A city develops

Having made the transition from small mining town to a municipality and then a large and wealthy borough, the town was declared a city on 21 July 1871. Bendigo (then known as Sandhurst) became established as a key centre for surrounding settlements.

A mining boom in the 1870s helped the city to continue to grow rapidly. By the late 1870s Sandhurst (Bendigo) had grown into a “fine handsome town” with nearly 28,000 residents in its urban area.[8] Growth then continued at a slower rate through to 1900.

Water supply was always a problem in Bendigo. This was partly solved with a system harnessing the waters of the Coliban River, designed by engineer Joseph Brady. Water first flowed through the viaduct in 1877.

Bendigo from its earliest days has been one of the major Cornish Australian settlement areas. In 1881 46.9 percent of fathers and 41.4 percent of mothers in Bendigo were born in Cornwall.[58] This was in addition to those Cornish who were born in Australia or places as far afield as Mexico or Brazil. The Cornish in Bendigo outnumbered the combined strength of their Irish and Scottish counterparts.[58]

The architect William Charles Vahland left a major mark on Bendigo during this period. He is credited as innovating what was the most popular residential design of the period, low cost cottages with verandahs decorated in iron lace which became a popular style right across Victoria. He transformed the Bendigo Town Hall between 1878 to 1886 into a grand building and designed more than 80 more public and private buildings, including the Alexandra Fountain, the Masonic Temple (now the Capital Theatre[59] ) and the Mechanics Institute and School of Mines (now the Bendigo Regional Institute of TAFE), "Fortuna Villa" in Golden Square (which was the home of "Quartz King" George Lansell), the Law Courts, former Post Office and the expanded Shamrock Hotel in Pall Mall.[60]

A tram network began in 1890 and was used for public transport.

20th century

From the start of the 1900s the population began to decline, especially in the rural areas.

Significant population growth occurred in the post-war years. As gold mining operations were reduced, Bendigo from the 1930s consolidated as a manufacturing and regional service centre and continued to grow steadily. Gold mining continuing in some capacity until the last mine was closed in 1954.

Growth has continued since the 1980s, aided by local economic and employment growth. Recent growth has been most heavily concentrated in areas such as Epsom, Kangaroo Flat, Strathdale and Strathfieldsaye.

On 7 April 1994 the City of Bendigo was abolished and mergered with the Borough of Eaglehawk, the Huntly and Strathfieldsaye shires and the Rural City of Marong to form the larger City of Greater Bendigo.[61][62]

21st century

The population of the city increased from around 78,000 in 1991 to about 100,617 in 2012.[4] Bendigo has consolidated its position as one of the fastest growing regional centres in Victoria, with growth expected to continue, especially in the new development areas of Huntly, Jackass Flat, Maiden Gully and Strathfieldsaye.

Land use

The City of Greater Bendigo includes Victoria's fourth largest city in Bendigo, as well as a significant rural hinterland. Smaller townships are located at Axedale, Elmore, Goornong, Heathcote, Marong and Redesdale. The city encompasses a total land area of 3,000 square kilometres, of which a significant proportion is national park, regional park, reserve or bushland. Much of the rural land is used for agricultural purposes, including poultry and pig farming, sheep and cattle grazing and vineyards. Most of the city's retail space is in the Bendigo CBD or along the main roads. There is some industrial land use in the suburbs around the CBD.

Major features

Major features of the City of Greater Bendigo include the Greater Bendigo National Park, the Heathcote-Graytown National Park, the Bendigo Regional Park, Lake Eppalock, Lake Weeroona, Ironbark Lookout, One Tree Hill Lookout, the Bendigo CBD, Lansell Plaza, the Bendigo Regional Institute of TAFE (Clinical Training Centre and BTEC, City and Charleton Road campuses), Monash University School of Rural Health (Bendigo Regional Clinical School), La Trobe University (Bendigo Campus), Bendigo School of Nursing, Bendigo Hospital, Bendigo Art Gallery, Central Deborah Gold Mine, Discovery of Gold Monument, Campaspe Run Rural Discovery Centre, the Discovery Science & Technology Centre, the Bendigo Tramways Museum, the Golden Dragon Museum, the Chinese Gardens, Bendigo Pottery, Sweenies Creek Pottery, Goldfields Mohair Farm, Hartlands Eucalyptus Factory, White Hills Botanic Gardens, Bendigo Racecourse, Diamond Hill Historic Reserve, the Campaspe River and numerous wineries.

Urban centre

The central area (CBD) of Bendigo consists of approximately 20 blocks of mixed use area. The main street is the Midland Highway, the section running through the CBD is also known as "Pall Mall" while the main shopping area is centred around Hargreaves Mall.

Suburbs

The contiguous urban area of Bendigo covers approximately 82 km2 of the local government area's 3048 km.

Bendigo has several suburbs some of which (such as Eaglehawk) were once independent satellite townships and many which extend into the surrounding bushland.

Bendigo's suburbs include Ascot, California Gully, Eaglehawk, Eaglehawk North, East Bendigo, Epsom, Flora Hill, Golden Square, Golden Gully, Junortoun, Kangaroo Flat, Kennington, Long Gully, Maiden Gully, North Bendigo, Quarry Hill, Sailors Gully, Spring Gully, Strathdale, Strathfieldsaye, West Bendigo and White Hills.

Architectural heritage

As a legacy of the gold boom Bendigo has many ornate buildings built in a late Victorian colonial style. Many buildings are on the Victorian Heritage Register and registered by the National Trust of Australia. Prominent buildings include the Bendigo Town Hall (1859, 1883–85), the Old Post Office, the Law Courts (1892–96), the Shamrock Hotel (1897), the Institute of Technology and the Memorial Military Museum (1921) all in the Second Empire-style.

The architect Vahland encouraged European artisans to emigrate to the Sandhurst goldfields and so create a "Vienna of the south".[63] Bendigo's Sacred Heart Cathedral, a large sandstone church, is the third largest cathedral in Australia and one of the largest cathedrals in the Southern Hemisphere. The main building was completed between 1896 and 1908 and the spire between 1954 and 1977.

Fortuna Villa is a large surviving Victorian mansion, built for Christopher Ballerstedt and later owned by George Lansell. Many other examples of Bendigo's classical architecture rank amongst the finest classical commercial buildings in Australia and include the Colonial Bank building (1887) and the former Masonic Hall (1873–74) which is now a performing arts centre. Bendigo's Joss house, a historic temple, was built in the 1860s by Chinese miners and is the only surviving building of its kind in regional Victoria which continues to be used as a place of worship. The historic Bendigo Tram Sheds and Power Station (1903) now house Bendigo's tramway museum. The Queen Elizabeth Oval still retains its ornate 1901 grandstand.

Parks and gardens

The central city is skirted by Rosalind Park, a Victorian-style garden featuring statuary and a large blue stone viaduct. The main entrance corner of the park is on the intersection known as Charing Cross, formerly the intersection of two main tram lines (now only one). It features a large statue of Queen Victoria.

The Charing Cross road junction features the large ornate Alexandra Fountain (1881) and is built on top of a wide bridge which spans the viaduct. The park elevates toward Camp Hill, which features a historic school and former mine poppet head.

Further from the city is Lake Weeroona, a large ornamental lake adjacent to the Bendigo Botanical Gardens, which opened in 1869.

The gardens are home to many native species of animal including brushtailed and ring-tailed possums, ducks, coots, purple swamphens, microbats (small insect eating bats) the grey-headed flying fox, several species of lizard, owls and the tawny frogmouth.

Demographics

(*) From preliminary ABS estimate

| Bendigo population by year[64][65][66] | |

|---|---|

| 1891 | 34,089[citation needed] |

| 1901 | 39,141[citation needed] |

| 1911 | 36,127[citation needed] |

| 1921 | 30,401[citation needed] |

| 1933 | 29,131[citation needed] |

| 1947 | 30,779[citation needed] |

| 1954 | 36,918[citation needed] |

| 1961 | 40,335[citation needed] |

| 1966 | 42,208[citation needed] |

| 1971 | 45,936[citation needed] |

| 1976 | 55,152[citation needed] |

| 1981 | 58,818[citation needed] |

| 1986 | 65,134[citation needed] |

| 1991 | [67] |

| 1996 | 59,936[68] |

| 2001 | 68,480[69] |

| 2006 | 76,051[70] |

| 2011 | 82,794 |

Economy

Bendigo is a large and growing service economy. The major industries are tourism, commerce, education and primary industries, with some significant engineering industries (see below under "Manufacturing").

Bendigo's growth is largely at the expense of small surrounding rural towns (such as Elmore, Rochester, Inglewood, Dunolly and Bridgewater) which in contrast are in steep decline.[citation needed]

Tourism

Tourism is a major component of the Bendigo economy, generating over A$364 million in 2008/09.[71] Bendigo is popular with heritage tourists and cultural tourists with the focus of tourism on the city's gold rush history. Prominent attractions include the Central Deborah Gold Mine, the Bendigo Tramways (both of which are managed by the Bendigo Trust, a council-intertwined organisation dedicated to preserving Bendigo's heritage), the Golden Dragon Museum and the Bendigo Pottery.

Commerce

The main retail centre of Bendigo is the central business district, with the suburbs of Eaglehawk, Kangaroo Flat, Golden Square, Strathdale and Epsom also having shopping districts.

The city is home to Australia's only provincial stock exchange, the Bendigo Stock Exchange (BSX), founded in the 1860s.

The city is the home of the headquarters of the Bendigo Bank; established in 1858 as a building society. it is now a large retail bank with community bank branches throughout Australia. The bank is headquartered in Bendigo and is a major employer in the city (it also has a regional office at Melbourne Docklands).

Manufacturing

The City of Greater Bendigo Community Profile indicated that about 10.2%% of the workforce were employed in manufacturing in 2011.[72] After the Victorian gold rush the introduction of deep quartz mining in Bendigo caused the development of a heavy manufacturing industry. Little of that now remains but there is a large foundry (Keech Castings) which makes mining, train and other steel parts and there is also a rubber factory. Thales Australia (formerly ADI Limited) is an important heavy engineering company. Australia Defence Apparel is another key defence industry participant making military and police uniforms and bulletproof vests. Intervet (formerly Ausvac) is an important biotechnology company, producing vaccines for animals.

Education

The Bendigo Senior Secondary College is the largest VCE (Victorian Certificate of Education) provider in the state. Catholic College Bendigo follows close after, which ranges from Years 7–9 at the La Valla campus and 10–12 at the Coolock campus. The Bendigo campus of La Trobe University is also a large and growing educational institution with over 5,000 undergraduates and postgraduates in its five faculties.

Farming and agriculture

The surrounding area, or "gold country", is quite harsh rocky land with scrubby regrowth vegetation. The Box-Ironbark forest is used for timber (mainly sleepers and firewood) and beekeeping.

Sheep and cattle are grazed in the cleared areas. There are some large poultry and pig farms. Some relatively fertile areas are present along the rivers and creeks, where wheat and other crops such as canola are grown. The area produces premium wines, including shiraz, from a growing viticulture industry. Salinity is a problem in many valleys, but is under control. There is a relatively small eucalyptus oil industry.

Bendigo provides services (including a large livestock exchange) to a large agricultural and grazing area on the Murray plains to its north.

Gold mining

One of the major revolutions in gold mining (during the Victorian gold rush) came when fields like Bendigo but also Ballarat, Ararat and the goldfields close to Mount Alexander turned out to have large gold deposits below the superficial alluvial deposits that had been (partially) mined out. Gold at Bendigo was found in quartz reef systems, hosted within highly deformed mudstones and sandstones or were washed away into channels of ancient rivers. Tunnels as deep as 2000 or even 3000 feet (600 to 900 metres) (Stawell) were possible.[73]

Until overtaken in the 1890s by the Western Australia goldfields, Bendigo was the most productive Australian gold area, with a total production of over 20 million ounces (622 tonnes).

Over the 100-odd year period from 1851 to 1954 the 3,600 hectare area which made up the Bendigo gold field yielded 25 miilion ounces (777 tonnes) of gold.[8]

There is a large amount of gold still in the Bendigo goldfields, estimated to be at least as much again as what has been removed. The decline in mining was partly due to the depth of mines and the presence of water in the deep mines.

Infrastructure

Transport

Bendigo is connected via the Calder Freeway to Melbourne, which is less than two hours by car.[74] The remaining section of highway nearest Bendigo has been upgraded to dual carriageway standard ensuring that motorists can travel up to speeds of 110 km/h (68 mph) for most of the journey. Many other regional centres are also connected to Melbourne via Bendigo, making it a gateway city in the transport of produce and materials from northern Victoria and the Murray to the Port of Melbourne and beyond.

Bendigo acts as a major rail hub for northern Victoria, being at the junction of several lines including the Bendigo railway line which runs south to Melbourne and lines running north including the Swan Hill railway line, Echuca railway line and Eaglehawk–Inglewood railway line. V/Line operates regular VLocity passenger rail services to Melbourne's Southern Cross Station with the shortest peak journeys taking approximately 91 minutes from Bendigo railway station, generally however services take two hours or longer. While there are several rail stations in the urban area, only two other stations currently operated for passengers: Kangaroo Flat railway station on the Bendigo Line and Eaglehawk railway station, the latter being the terminus for some services from Melbourne. There are also additional train services to and from Swan Hill and Echuca. The Regional Rail Link promises more reliable services between Bendigo and Melbourne by providing some separation from the Melbourne metropolitan rail network. Victoria's electronic ticketing system, Myki, was implemented on rail services between Eaglehawk and Melbourne on 17 July 2013.[75]

Bendigo is also served by an extensive bus network which radiates mostly from the CBD towards the suburbs. The city is also serviced by several taxi services.

Trams in Bendigo have historically operated an extensive network as a form of public transport, however the remains of the network was reduced to a tourist service in 1972.[76] Short trials of commuter tram services were held in 2008 and 2009 with little ridership. The second, "Take a Tram", proved more successful, running twice as long as the previous trial. By the end of the "Take a Tram" program, ridership had increased and was increasing. However, due to lack of government subsidy or backing, the program ended.[77]

Bendigo is served by the Bendigo Airport, which is located to the north of the city on the Midland Highway. The Bendigo Airport Strategic Plan was approved in 2010 for proposed infrastructure upgrades including runway extension and buildings to facilitate larger planes and the possibility of regular passenger services from major cities in other states.[78]

Health

The Bendigo Base Hospital is the city's largest hospital, only public hospital and a major regional hospital. St John of God is the largest private hospital. Bendigo is also served by a privately owned smaller surgical facility, Bendigo Day Surgery.

Utilities

Bendigo is entitled to a portion of the water in Lake Eppalock, an irrigation reservoir on the Campaspe River. Developments have led to the building of a pipeline from Waranga to Lake Eppalock and thence to Bendigo in 2007. There is a dam (and a road) called Faugh A Ballagh.

Culture and events

The Bendigo Art Gallery is one of Australia’s oldest and largest regional art galleries. In March 2012, it hosted a royal visit from Princess Charlene of Monaco at the opening of an exhibition about Grace Kelly.[79]

The Capital Theatre, originally the Masonic temple, is located next to the art gallery in View Street and hosts performing arts and live music.

The city hosts the Bendigo National Swap Meet for car parts every year in early November. It is regarded as the biggest in the southern hemisphere and attracts people from all over Australia and the world.

The city hosts the Victorian event of the annual Groovin' the Moo music festival. It is held at the Bendigo Showgrounds and is usually held in late April or early May. The festival regularly sells out and brings many big Australian and international acts to the city. It also attracts thousands of people from around Victoria to the city for the weekend.

The Bendigo Blues and Roots Music Festival has been taking place each November since 2011. With over 80 artists from all over Australia, the not-for-profit festival is hosted in many of the venues around Bendigo, and is headlined by a large family-friendly free concert held in Rosalind Park.

The Bendigo Easter Festival is held each year and attracts tens of thousands of tourists to the city over the Easter long weekend. Attractions include parades, exhibitions and a street carnival.

The Bendigo Queer Film Festival (BQFF) is one of Australia's few regional cities to host an annual film festival celebrating the Queer film genre. In 2013 the BQFF celebrated its tenth anniversary.

Media

Bendigo is served by two newspapers: the Bendigo Advertiser and the Bendigo Weekly. There are also six locally-based radio stations; (EasyMix Ten71am and 98.3FM) Star FM, 3BO FM and ABC Local Radio as well as the community radio stations Radio KLFM 96.5, Phoenix FM and 101.5 Fresh FM.

Regular network television is broadcast in the Bendigo region by the WIN, Prime, Southern Cross Ten, ABC and SBS. Local programming consists of 30-minute weeknight news bulletins on WIN and short news updates on Southern Cross Ten. Prime Television maintains a sales office in Bendigo.

On 5 May 2011, analogue television transmissions ceased in most areas of regional Victoria and some border regions including Bendigo and surrounding areas. All local free-to-air television services are now being broadcast in digital transmission only. This was done as part of the federal government's plan for digital terrestrial television in Australia, where all analogue television transmission is being gradually switched off and replaced with DVB-T transmission.

Music

There are several live music venues with local independent bands and artists performing on a regular basis. There also several adult choirs and the Bendigo Youth Choir which often performs overseas, the Bendigo Symphony Orchestra, the Bendigo Symphonic Band, Bendigo & District Concert Band, several brass bands and three pipe bands.[80] Musicians originally from Bendigo include Patrick Savage – film composer[81] and former principal first violin of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London.[82] Australian Idol winner Kate DeAraugo grew up in Bendigo where her family still live.[83][84]

Sport

Cricket and Australian rules football are the most popular sports in Bendigo. The Queen Elizabeth Oval (referred to locally as the "QEO") hosts both sports. The Bendigo Gold are a semi-professional Australian Rules team that competes in the Victorian Football League. The Bendigo region is also home to the historic Bendigo Football League, a strong local Australian rules football competition.

The Bendigo Cup is a prominent horse racing event. The Bendigo and District Cricket Association is the controlling body for 10 senior cricket clubs within the Bendigo area. The Emu Valley Cricket Association organises matches for 13 clubs around the Bendigo district, from Marong in the north to Heathcote is the south. The Bendigo Madison is a large and notable cycling event, attracting international calibre cyclists.

Bendigo hosts the richest professional running 400m in the world. Called the Black Opal, it is held in March each year and usually sees thousands of people at the venue with professional running races as well as cycling events (featuring the Bendigo Madison) over a two-day carnival. The 400 m Black Opal and 120 m Bendigo Gift finals are conducted before the Bendigo Madison on the second night (Sunday) of the carnival.

Tennis is popular in Bendigo with the Bendigo Tennis Association (BTA) hosting local, state, national and international tournaments at its many court locations throughout the city. The 30 synthetic hard court Bendigo Bank Tennis Complex next to Lake Weeroona is one of the largest in the southern hemisphere. The Bendigo Lawn Tennis Club also has 16 natural grass courts, one of the largest in the region.

Swimming is a popular year-round sport in Bendigo. There are two competitive clubs, the Bendigo Hawks Aquatic club and the Bendigo East swimming club.The home of the Bendigo Hawks Aquatic is located at the Peter Krenz Leisure Centre in Eaglehawk in the city's north-west. Among many other fitness and leisure facilities the centre boasts Central Victoria's only 50m, heated indoor swimming pool. During the summer months the Club also train and compete in their 50m outdoor pool at the Bendigo Aquatic Centre located in the heart of the City. Both pools provide for year-round training and competition for swimmers of all ages across the City of Greater Bendigo. A competition-class 50m pool can also be found at the Bendigo East Aquatic Centre.

Basketball is popular in Bendigo with professional men's and women's games played at the Bendigo Stadium. The stadium hosted basketball during the 2006 Commonwealth Games. Bendigo's men's team is called the Bendigo Braves and the women's team is called Bendigo Spirit. In 2013 the women's team won the Women's National Basketball League championship. The city is also home to the Bendigo Basketball Association.

Bendigo was the host to the second Commonwealth Youth Games, held from 30 November to 3 December 2004.

Soccer: The Bendigo Amateur Soccer League organises and manages soccer for over 3000 juniors and seniors in Central Victoria. Bendigo is also home to the largest junior soccer club in Victoria, Strathdale Soccer Club. Bendigo along with Swan Hill, Echuca and Mildura have a team in Football Federation Victoria's Summer league. The team is the Loddon Mallee FC.

Rugby Union: The Bendigo Fighting Miners, founded in 1970, are the only team in Bendigo and competes in the Victorian Country Rugby Union Competition and won the four years in a row in the period 2003 to 2006.[85]

Hockey: The CVHA Blazers represent Bendigo in hockey at state level in both male and female competitions. The Bedigo Raiders Ice Hockey Team competes at both junior and senior levels within the Victorian ice hockey Association and is the only team to play that is located outside Melbourne.

Ice Skating: Bendigo also has an ice skating club, the Ice Skating Club of Bendigo, which was instrumental in organising regional and state skating competitions. The closure of the ice rink in 2010 has limited its activities.

Baseball: There are four running clubs in the Bendigo area: Eaglehawk Falcons, Bendigo East, Maiden Gully Scots, and Strathfieldsaye Dodgers. Bendigo participates in the annual VPBL state championships held across the state.

Orienteering: The Bendigo Orienteers Inc have hosted a variety of international carnivals including the 1985 World Orienteering Championships (4–6 September 1985) and the World Masters Games orienteering events in 2002. Bendigo has also hosted several Australian Orienteering Championships including those held in September 2009.

Volleyball: Bendigo has a very strong volleyball association, with five senior divisions, five junior divisions and three Spikezone (primary) divisions. Competition is played on Thursday nights at the Bendigo Schweppes Centre and Sunday evenings (Spikezone). A number of players have represented Australia including Caitlin Thwaites and Erin Ross in the women's team. Juniors to have represented Australia in 2007–8 include Jason Hughes, James Winzar, Rhiannon Judd and Karley Hynes. In 2007 the Bendigo Volleyball Association was awarded the Event of the Year for 2006-7 by the AVL for its hosting of the Australia v Argentina volleyball test.

Lacrosse: The Bendigo Lacrosse Club is Australia's newest lacrosse club, having been officially formed in 2008. The club is based at the Latrobe University Bendigo Athletics Track. In 2010, the club participated in the Lacrosse Victoria competition for the first time, in the Division 3 (fourth grade) senior level. The club is also looking to establish a local junior competition and encourages anyone interested in lacrosse to get involved. It is the first time in over 40 years that a lacrosse club has been active in regional Australia.

Snooker – As of 2011, Bendigo has played host to a ranking World Snooker Tour event – The Australian Goldfields Open. The 2011 tournament took place between 18 and 24 July, and was won by Stuart Bingham.[86][87]

Bendigo has a horse racing club, the Bendigo Jockey Club, which schedules around 22 race meetings a year at its Epsom track, including the Bendigo Cup meeting in mid-November.[88] Elmore Racing Club also hold their only meeting here in March.[89]

Bendigo Harness Racing Club conducts regular meetings at its racetrack in the city at Lords Raceway on the McIvor Highway, Junortoun.[90]

The Bendigo Greyhound Racing Club holds regular meetings at the same location.[91]

Golfers play at the course of the Bendigo Golf Club on Golf Course Road in the suburb of Epsom[92] or at the course of the Quarry Hill Golf Club on Houston Street.[93]

Environment

The city is surrounded by components of the Greater Bendigo National Park, as well as the Bendigo Box-Ironbark Region Important Bird Area, identified as such by BirdLife International because of its importance for Swift Parrots and other woodland birds.[94] A dozen species of insect eating bats and the pollinating grey-headed flying fox inhabit the area.

Climate

Bendigo experiences an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb),[5] typically dry and mild with cold winters. High temperatures are usually recorded during the beginning and end of the year with the rest of the year experiencing moderate temperatures.

The mean minimum temperature in January is 14.3 °C (57.7 °F) and the maximum 28.7 °C (83.7 °F), although temperatures above 35 °C (95.0 °F) are commonly reached.[5] The highest temperature officially recorded was 45.4 °C (113.7 °F), during the early 2009 southeastern Australia heat wave.[95] There is also a disputed recording of 47.4 °C (117.3 °F) (on 14 January 1862).[96] The mean minimum temperature in July is 3.5 °C (38.3 °F) and winter minima of below 0 °C (32 °F) have been recorded frequently. Mean maximum winter temperatures in July are 12.1 °C (53.8 °F). Most of the city's annual rainfall of 582.1 millimetres (22.92 in) falls between April and October. Snowfalls are virtually unknown, however frosts can be a common occurrence during the winter months.

| Climate data for Bendigo Airport (YBDG) since 1991 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 43.6 (110.5) |

45.4 (113.7) |

38.6 (101.5) |

33.7 (92.7) |

26.3 (79.3) |

20.7 (69.3) |

19.7 (67.5) |

24.2 (75.6) |

30.4 (86.7) |

35.5 (95.9) |

40.3 (104.5) |

43.1 (109.6) |

45.4 (113.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.7 (85.5) |

29.4 (84.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

12.5 (54.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.3 (68.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

27.0 (80.6) |

20.9 (69.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

14.3 (57.7) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

5.1 (41.2) |

3.5 (38.3) |

2.5 (36.5) |

2.6 (36.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

7.8 (46) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−5.0 (23) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 35.0 (1.378) |

36.1 (1.421) |

29.8 (1.173) |

27.3 (1.075) |

45.6 (1.795) |

50.5 (1.988) |

53.3 (2.098) |

51.5 (2.028) |

50.1 (1.972) |

41.9 (1.65) |

47.8 (1.882) |

42.2 (1.661) |

509.4 (20.055) |

| Source: [97] | |||||||||||||

Extreme weather events

A series of great floods occurred in Bendigo in 1859.[98][99] Substantial flooding also occurred in 1903.[100]

Tornadoes have been seen around the area of Bendigo and, although rare, the 2003 Bendigo tornado passed through Eaglehawk and other parts of the city causing major damage to homes and businesses.[101]

Bendigo was in severe drought from 2006 to 2010 and during this time the city had some of the harshest water restrictions in Australia, with no watering outside the household. Heavy rains from the middle to later months of 2010 filled most reservoirs to capacity and only wasteful water use (e.g. hosing down footpaths) is currently banned.[102]

Bendigo was affected by the Black Saturday bushfires in 2009. A fire to the west of the city burned out 500 hectares (1,200 acres).[103] The fire broke out at about 4.30 pm on the afternoon of 7 February, and burned through Long Gully and Eaglehawk, coming within 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) of central Bendigo, before it was brought under control late on 8 February.[103] It destroyed approximately 58 houses in Bendigo's western suburbs, and damaged an electricity transmission line, resulting in blackouts to substantial parts of the city.[104] There was one fatality from the fire.

Flash floods occurred across Bendigo during 2010, the first in March[105] and the most severe at the beginning of September.[106]

Sister cities

Notable residents

- Politics

- John Bannon, Labor Premier of South Australia, 1982–1992

- Frank Brennan, Federal Attorney-General, 1929–31

- Tom Brennan, older brother of Frank and Federal UAP Senator, 1931–37

- John Brumby, Labor Premier of Victoria, 2007–2010

- John Gunn, Labor Premier of South Australia, 1924–26

- Edward Heitmann, Federal Labor politician, 1917–1919

- John Lutey, Labor Party member of the West Australian parliament, 1917–1932

- Peter Ryan, current leader of the Victorian National Party

- Sport

- AFL players – Graham Arthur, Nathan Brown, Wayne Campbell, Nick Dal Santo, Eric Fleming, Trevor Keogh, Barry Mulcair, Troy Selwood, Adam Selwood, Joel Selwood, Scott Selwood, Geoff Southby, Colin Sylvia, Brian Walsh, Greg Williams

- Don Blackie, Test cricketer

- Hannah Every-Hall, rower

- Kristi Harrower, national basketballer

- Stephen Huss, 2005 Wimbledon men's doubles champion

- Faith Leech, Olympic swimming champion

- Billy Murdoch, Australian Test cricket captain

- Ricky Nixon, sports agent and former AFL footballer

- Lisle Nagel, Australian Test cricketer

- Glen Saville, Australian and NBL basketballer

- Ben Hunt, NCAA, NBA and NBL basketballer

- Craig White, English cricket player

- Sharelle McMahon, Australian Netball Team captain, Melbourne Vixens captain

- Arts

- Bunney Brooke, TV actress

- Kate DeAraugo, 2005 Australian Idol winner

- Colleen Hewett, singer and actress

- Keith Lamb, lead singer of Hush

- Ernest Moffitt, artist

- William Moore, art and drama critic

- William David Murdoch, concert pianist

- John Bernard O'Hara, poet and schoolmaster

- Alfred Henry O'Keeffe, artist

- Ian Rilen, bass guitarist with Rose Tattoo

- Russell Jack, founder and director of the Golden Dragon Museum

- Science

- John Irvine Hunter, professor of anatomy

- Struan Sutherland, antivenin researcher

- Geoffrey Watson, professor of statistics

- Frank Milne, professor of economics

- Business

- Frank McEncroe, inventor of the Chiko Roll

- Sidney Myer, philanthropist and founder of the Myer chain of department stores, Australia's largest retailer

- Religion

- Sydney James Kirkby, Anglican bishop

- Military

- Carl Jess, Australian Army Lieutenant General

- John Campbell Ross, last Australian World War I veteran

- Sir Gilbert Dyett, long-serving President of the Returned and Services League of Australia

See also

- List of Mayors of Bendigo

- Bendigo Easter Festival

- HM Prison Bendigo

- Bendigo Senior Secondary College

- Flora Hill Secondary College

- Golden Square Secondary College

- Catholic College Bendigo

- 2003 Bendigo tornado

References

- ↑ http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/quickstat/UCL211003?opendocument&navpos=220

- ↑ http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/communityprofile/UCL211003

- ↑ http://www.bendigo.vic.gov.au/page/page.asp?page_Id=1711&h=0

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 ABS website "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2008–09". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 30 March 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bendigo Campus, Latrobe - About Bendigo

- ↑ Earliest reference in a newspaper digitised on-line by the National Library of Australia to the term "Bendigonian" "The Northern Gold Fields". The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser (NSW : 1843 - 1893) (Maitland, NSW.: National Library of Australia). 18 January 1854. p. 2. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "Bendigo". Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer (Vic. : 1851 - 1856) (Geelong, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 29 August 1854. p. 4. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 8.10 State of Victoria Early Postal Cancels (and History) Illustrated, Section II: 1851 to 1853

- ↑ Burke and Wills

- ↑ Bendigo Advertiser (Vic. : 1855 - 1918) 3 May 1856, p. 2.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 David Horsfall, "Who Discovered Bendigo Gold?", Australian Institute of Genealogical Studied Inc., Bendigo Area, 2009, p.12

- ↑ David Hosfall, "Who Discovered Bendigo Gold?", Australian Institute of Genealogical Studies Inc., Bendigo Area, 2009, p.13

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 "Mount Alexander (Bendigo Creek)". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 13 December 1851. p. 2. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Bendigo Creek Diggings". Geelong Advertiser (Vic. : 1847 - 1851) (Geelong, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 13 December 1851. p. 2. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cited in "The Discovery Of Bendigo". Bendigo Advertiser (Vic. : 1855 - 1918) (Bendigo, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 12 September 1890. p. 3. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Social And General – A select committee of the Legislative Assembly". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 4 November 1890. p. 9. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Bendigo Cemetery Walking Tours; Bendigo - The Name

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "The Pioneers Of Gold Discovery On Bendigo", Bendigo Advertiser (Vic. : 1855 - 1918), 28 October 1893, p.3

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 "The discovery of Bendigo gold-field". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 23 September 1890. p. 7. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Letter from Mrs. W. Lauder to the Select Committee of 1890 recollecting her conversation with Thomas Myers in 1852 about where the name of "Bendigo" had come from, cited: in David Horsfall, "Who Discovered Bendigo Gold?", Australian Institute Of Genealogical Studied Inc., Bendigo Region, 2009, p.43-44

- ↑ David Horsfall, "Who Discovered Bendigo Gold?", Australian Institute Of Genealogical Studies Inc., Bendigo Area, 2009, p.44

- ↑ "City Of Greater Bendigo, Heritage Policy Citations Project, Lovell Chen 2010", p.144. The reference to Thomas Myers being a squatter on the 'Weddikar Run' from the earlier date of 1845 is incorrect as "The Argus" of 3 October 1848 states that the leaseholders were John Nicholson and William Myers.

- ↑ "Origin Of The Name "Bendigo"". Australian Town and Country Journal (NSW : 1870 - 1907) (Sydney, NSW.: National Library of Australia). 21 September 1878. p. 17. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "Discovery Of Gold At Bendigo". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 9 September 1890. p. 9. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Discovery Of Gold At Bendigo". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 5 September 1890. p. 7. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "The Discovery Of Gold At Bendigo - a letter from William Sandbach one of the first diggers on the Bendigo Goldfield". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 13 September 1890. p. 10. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ A search of the on-line digitised archive for Australian Newspapers at the National library of Australia during the period 1854 to 1891 reveals many references to the use of the name "Bendigonian" to refer to a resident of Sandhurst (Bendigo).

- ↑ "The Straight Tip". Bendigo Advertiser (Vic. : 1855 - 1918) (Bendigo, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 28 April 1891. p. 3. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Name "Bendigo" (Editorial)". Bendigo Advertiser (Vic. : 1855 - 1918) (Bendigo, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 25 January 1890. p. 4. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ Kennedy Family

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Discovery Of Gold", Bendigo Historical Society

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Discovery Of Bendigo". Bendigo Advertiser (Vic. : 1855 - 1918) (Bendigo, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 26 September 1890. p. 3. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ Henry Frencham

- ↑ Cited in "Geelong Advertiser", Monday 16 June 1851, p.2

- ↑ David Horsfall, "Who Discovered Bendigo Gold?", Australian Institute of Genealogical Studies Inc., Bendigo Area, 2009, p.49-50]

- ↑ "Yuille's digging". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 19 September 1851. p. 2. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 "The First Gold Discovery At Bendigo – Mr. H. Frencham’s Claim". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 12 September 1890. p. 7. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ David Horsfall, "Who Discovered Bendigo Gold?", Australian Institute of Genealogical Studies Inc., Bendigo Area, 2009, p.53

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Friday, October 24, 1890 - The report of the select committee". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 24 October 1890. p. 5. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Discovery Of The Bendigo Gold–Field, Mr Frencham’s Claim". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 3 October 1890. p. 10. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Discovery Of Gold At Bendigo, Conclusion Of Evidence". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 10 October 1890. p. 10. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "Parliament – Discovery Of The Bendigo Gold-Field". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957) (Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 24 October 1890. p. 9. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ John Kennedy and Margaret McPhee

- ↑ John Drane and Margaret McPhee

- ↑ Victorian Birth Registrations: John Drane 1842 Melbourne #12750, Mary Kennedy 1849 Melbourne #4157 (Mary Ann Drane 1844 Melbourne #13680 - deceased before 1849)

- ↑ "Gold Discoverer's Daughter - Margaret(sic) Polglaise", The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), 14 April 1941, p.5

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Bendigo General History, Department of Planning and Community Development, citing from Frank Cusack, "Bendigo: a History", 1973

- ↑ David Horsfall, "Who Discovered Bendigo Gold?", Australian Institute of Genealogical Studies Inc., Bendigo Area, 2009, p.57 and 61.

- ↑ "The Discovery Of Bendigo". Bendigo Advertiser (Vic. : 1855 - 1918) (Bendigo, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 12 September 1890. p. 3. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Diggings". Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer (Vic. : 1851 - 1856) (Geelong, Vic.: National Library of Australia). 22 December 1851. p. 2. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Traveller's Guide to the Goldfields", 2006, Best Shot! Publications

- ↑ Premier Postal History. "Post Office List". Retrieved 11 April 2008

- ↑ Chinese History, Bendigo

- ↑ Monster Meeting

- ↑ Harrison, John (1802–1869)

- ↑ The Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston, Tas. : 1835 - 1880), 17 January 1852, p.35

- ↑ Alfred Howitt's Despatches & Letters

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Payton, Philip, Making Moonta: The Invention of Australia's Little Cornwall

- ↑

- ↑ Obituaries Australia - Vahland, William Charles (1828–1915)

- ↑ Municipal Association of Victoria (2006). "Greater Bendigo City Council". Retrieved 2008-01-08. Date cross-checked with the Records Division, Greater Bendigo City Council.

- ↑ Taylor, Thomas (6 April 1994). "Marong to fall in line on super council". The Age. p. 6. Accessed via Factiva online.

- ↑ "Vienna Of The South" (Bendigo), Vic

- ↑ I. McCalman, A. Cook, A. Reeves (2001). Gold: Forgotten Histories and Lost Objects of Australia. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ↑ 3105.0.65.001 – Australian Historical Population Statistics, 2006. Abs.gov.au. Retrieved on 18 August 2011.

- ↑ Census 2006 AUS id=2030 name=Bendigo (VIC) (Statistical District) accessdate=27 September 2007

- ↑ http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/free.nsf/0/6FD042C8ABF4B16BCA2574BE0083CC33/$File/27302_1991_170_Census_Counts_for_Small_Areas_-_%20Victoria.pdf

- ↑ http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2016.0Main+Features11996?OpenDocument

- ↑ http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/LocationSearch?locationLastSearchTerm=bendigo&locationSearchTerm=bendigo&newarea=UCL204800&submitbutton=View+QuickStats+%3E&mapdisplay=on&collection=Census&period=2001&areacode=UCL204800&geography=&method=Location+on+Census+Night&productlabel=&producttype=QuickStats&topic=&navmapdisplayed=true&javascript=true&breadcrumb=PL&topholder=0&leftholder=0¤taction=104&action=401&textversion=false&subaction=1

- ↑ http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/ProductSearch?&areacode=UCL204800&producttype=QuickStats&action=401

- ↑ http://121.50.208.46/bendigo/BTB%20AnnRep%20FINAL.pdf

- ↑ City Of Great Bendigo - Industry sectors of employment

- ↑ AMJ Ferguson. Gold, Gems and Pearls in Ceylon and Southern India. London, John Haddon & Co. p. 283 URL: Gold, Gems, Pearls Ceylon, Australian Gold Fields Discussion

- ↑ Google Maps calculates the distance from Bendigo to Melbourne to be 153 km (95 mi) and the time of travel is estimated to be 1 hour 47 minutes.

- ↑ "Myki to start on VLine Commuter Services". VLine Pty Ltd. Retrieved 2013-08-07.

- ↑ "The Bendigo Trust". www.bendigotrust.com.au. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ↑ "Tram trial gets mixed results". Tram Talk. Friends of the Bendigo Tramways. Autumn Issue, 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ↑ http://www.bendigo.vic.gov.au/Files/Bendigo_Airport_Strategic_Plan_adopted_3_June_2009.pdf

- ↑ The Age: "A fairytale in Bendigo" http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/a-fairytale-in-bendigo-as-charlene-enters-with-grace-20120310-1urgh.html

- ↑ "Arts Register". City of Greater Bendigo. 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm2747682/

- ↑ Woman, The. (26 August 2010) Sample a Bit of the Score from Fetch | Horror Movie, DVD, & Book Reviews, News, Interviews at Dread Central. Dreadcentral.com. Retrieved on 18 August 2011.

- ↑ Kate DeAraugo

- ↑ Kate DeAraugo Biography

- ↑ Bendigo Fighting Miners Rugby Union Football Club - Club History

- ↑ Article on BBC Sport Website. BBC News (23 May 2011). Retrieved on 18 August 2011.

- ↑ Article on BBC Sport Website. BBC News (24 July 2011). Retrieved on 18 August 2011.

- ↑ Country Racing Victoria. "Bendigo Jockey Club". Retrieved 7 May 2009

- ↑ Country Racing Victoria. "Elmore Racing Club". Retrieved 7 May 2009

- ↑ Australian Harness Racing. "Bendigo". Retrieved 11 May 2009

- ↑ Greyhound Racing Victoria. "Bendigo". Retrieved 15 April 2009

- ↑ Golf Select. "Bendigo". Retrieved 11 May 2009

- ↑ Golf Select. "Quarry Hill". Retrieved 11 May 2009

- ↑ "IBA: Bendigo Box-Ironbark Region". Birdata. Birds Australia. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ↑ "The exceptional January–February 2009 heatwave in south-eastern Australia", Bureau of Meteorology (National Climate Centre), 12 February 2009: 2

- ↑ Aikman, Rod (8 February 2003). "Weather history preserved". Bendigo Advertiser. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "Climate statistics for Bendigo". Bureau of Meteorology. April 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848–1954) 30 May 1859, p. 6.

- ↑ The Courier (Hobart, Tas. : 1840–1859) 20 May 1859, page 2

- ↑ The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848–1954) 29 December 1903, p. 6.

- ↑ "'Mini tornado' wreaks havoc – theage.com.au". Melbourne: www.theage.com.au. 19 May 2003. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ↑ Coliban Water – Permanent Water Saving Rules. Coliban.com.au. Retrieved on 18 August 2011.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 "Meeting held for fire-affected Bendigo residents". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ↑ Power, Emily; Collier, Karen (9 February 2009). "The man up the road is on fire". Herald Sun (Australia). Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ↑ Bendigo flood clean-up, then the cost – Local News – News – General – Bendigo Advertiser. Bendigoadvertiser.com.au (8 March 2010). Retrieved on 18 August 2011.

- ↑ Deluge causes flood havoc across central Victoria – Local News – News – General – Bendigo Advertiser. Bendigoadvertiser.com.au (5 September 2010). Retrieved on 18 August 2011.

- ↑ "Sister Cities". City of Greater Bendigo. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bendigo. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bendigo, Victoria. |

- Bendigo Economic Profile

- Bendigo Tramways

- Bendigo Visitor Information and Interpretive Centre

- City of Greater Bendigo website

- City of Greater Bendigo Community Profile - Population, Employment, Maps, Forcasts & Economy

- Victorian Heritage Register (1999), Heritage Victoria

- Bendigo Polished Concrete - Ultra Grind

- Bendigo Onsite Technical Support

- Bendigo Website Design

| ||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||