Belfield (Philadelphia)

|

Charles Willson Peale House | |

.jpg) | |

|

Charles Willson Peale House | |

| |

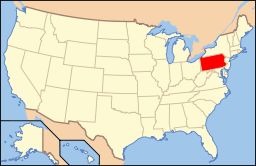

| Location | 2100 Clarkson Ave., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°2′16.6″N 75°9′19.53″W / 40.037944°N 75.1554250°WCoordinates: 40°2′16.6″N 75°9′19.53″W / 40.037944°N 75.1554250°W |

| Built | 1755 |

| Architect | Unknown |

| Architectural style | Dutch Colonial |

| Governing body | Private |

| NRHP Reference # | 66000687 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | December 21, 1965[2] |

Belfield, also known as the Charles Willson Peale House, was the home of Charles Willson Peale from 1810 to 1826, and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965.[2][3] The Belfield Estate was a 104-acre (42 ha) area of land in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, much of which is now a part of La Salle University’s campus.

Early History

In 1684, William Penn granted to Thomas Bowman 588 acres (238 ha) near Germantown.[4] Bowman kept the land for two years, and sold it to Samuel Richardson, a Quaker who was active in the early colonial government of Pennsylvania. The property extended from Old York Road to the edges of Germantown, with Richardson's home, "Newington", located on Old York Road.[5]

Upon Samuel Richardson's death in 1719, his son Joseph inherited the land, and split it among his children, with the area that would become Belfield going to his second son, John. John Richardson sold a portion of the land to John Eckstein in 1731. The 1731 deed mentions "Buildings & Woods & Underwoods, Timbers, Trees, Meadows, Marshes."[6] This is the first time that "buildings" are recorded on the property. The once free-standing, square structure now attached to the rear of the main house is believed to be the oldest surviving building, but it is not known whether this building existed at the time of the sale to Eckstein.

Eckstein transferred the land that the main house is located on to his daughter Magdalena and son-in-law Conrad Weber in 1755, and after the death of Eckstein in 1763 the land was split among his remaining children. Two of the remaining children of Eckstein became members of the religious Ephrata Cloister in Lancaster County, and all had sold their land to Weber by 1786.[7] Though the exact date of construction of the main house at Belfield is not known, Peale later wrote that it was built "by a Dutchman".[8] As Weber was the son of a Dutch immigrant, this would date the house to sometime after 1755.

Weber sold the property to his tenant Richard Neave in 1804, not having lived on the property himself since the 1770s. Neave owned the property until his death in 1809, when it was sold to his tenants, Charles and Mary Grégoire. The Grégoires possessed the property for just three months before putting it up for sale.[9]

Charles Willson Peale

Seeking to retire, Charles Willson Peale turned over the administration of his natural history museum to his son, Rubens, and began to look for a small country estate.[10] He purchased the land in 1810 from Charles Grégoire for $9500. Peale initially named the estate 'Farm Persevere', and wrote to Thomas Jefferson, telling him that this was because "by labor and perseverance I obtained it."[11] Friends of Peale's thought that this name was far too solemn, and as a result, by 1812 he had changed it to 'Bellefield', which later, became 'Belfield.'[12]

Peale began renovations on the mansion house after purchasing the property, separating partitions in between rooms, and adding a "painting room to the north side of the house. When this room was destroyed in a storm in August 1817, a larger, two-story addition was added.[13]

In October 1821, Peale and his wife Hannah contracted yellow fever, which led to Hannah's death. A weakened Peale moved in with his son Rubens, and put Belfield up for sale. In January 1826, William Logan Fisher, who's estate of Wakefield bordered Belfield to the southeast, purchased the property for $11,000.[14]

Peale's Gardens

Peale cultivated, and frequently used as inspiration, extensive gardens on the estate grounds. One of the first structures Peale added to his garden was a "summer house", built in about 1813 by his son Franklin. It was a hexagonal structure with six columns, and a bust of George Washington crowning its roof.[15] The Wister family later built a gazebo on this site that as of 2011 is in a ruined state. Northwest of the summer house was an obelisk at the end of a garden walk. Peale painted four mottos that governed his life on the base of this obelisk, one on each side. It was Peale's wish to have been buried at the foot of this obelisk, yet it was not to be, as Peale sold Belfield a year before his death.[16] Though Peale was not buried at this location, the Wister family later buried their dog, a white German Spitz named 'Kaiser', there.[17] A reproduction of this obelisk was created by La Salle alumni in 2000.[18]

To the south of the obelisk, Peale erected another summer house, in "chinease [sic] taste, dedicated to meditation.[19] This summer house was simpler than the one built by his son, and only had a flat roof to provide shade, and four posts to hold it up, with seats around the inside.[20] On the same hillside as the Chinese summer house was a pedestal onto which Peale inscribed ninety memorable events in American history, starting with the discovery of America, and ending with the American victory at New Orleans in 1815. Significantly, he left room to inscribe the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by an American steamship.[19]

Another contribution Peale made to his garden was the excellent use of one of the estate's natural springs. Peale hollowed out the source of the spring into an artificial cave, which he lined with masonry. This spring fed a greenhouse with a glass ceiling. To the southeast was a pool with a ten-foot fountain that was fed by pipes from the spring. Next to the pool was a garden shed onto which Peale painted a "gate" to disguise it. On the "gate" were symbols and figures representing Congress, America, Truth, Wisdom, Temperance, and Mars, the god of war.[21] The ruins of Peale's cave and greenhouse still stand. The cave is now underneath the stump of a coffee tree, but deteriorating the masonry is still visible.[19] The greenhouse's walls are to the west, and are mostly overgrown with brush and ivy. The location of Peale's pond has been paved over by a driveway.

After Peale

After purchasing the property from Peale, William Logan Fisher gave it to his daughter Sarah upon her marriage to William Wister in 1826.[22] According to the Wister's great-granddaughter, Mary Meigs, Belfield served as a stop on the Underground Railroad, though there is no contemporary evidence of this claim.[23] During this time, William Wister and William Logan Fisher together founded the Belfield Print Works, located at the edge of the property, at the present-day intersection of Belfield Avenue and Wister Street. Willaim Rotch Wister, the Wister's eldest son, and father of horticulturist John Caspar Wister, had a house constructed on the estate in 1868 for his family, this house is now La Salle's Mary and Frances Wister Fine Arts Studio. In 1876, he moved his family across the street to another house he had built, the mansion 'Wister', which was deeded to Fairmount Park and demolished in 1956.[24]

The Wister's second son, John, purchased the remaining property upon Sarah's death in 1891. John Wister made several improvements to the property, installing a furnace in the main house, and building a greenhouse next to the ruins of Peale's. The foundations of this greenhouse survive as of 2010. In July 1907, the carriage house caught fire, causing the panicked Wister family to flee Belfield, though there was no actual damage to the main house.[25] After John died in 1900, his wife Sallie Wister continued to live at Belfield until her death in 1922. Upon her death, it was discovered that John Wister's will gave Belfield to his second daughter Sarah Logan Wister Starr, who had lived in another house on the property, later dubbed 'The Mansion', since her marriage in 1901.[26] Wister's eldest daughter, Bessie, felt slighted, leading to a feud between the sisters lasting several decades.[27]

During the ownership of Sarah and her husband James Starr, the property had bathrooms installed and underground electric and telephone lines run to it. They had the colonial kitchen restored, and planted citrus trees, and a garden of one hundred Tea Roses. James, who had an interest in China added several rock gardens and in the rear of the main house, a "Chinese Garden" that still survives. The date of the garden's construction was recorded in Chinese characters on the garden's wall. Also during the Starr's ownership, 20th Street was constructed and a deep trench was cut in the hillside, requiring a 14 foot retaining wall be built along what is now the eastern edge of the estate.[28] In 1926, La Salle College purchased a portion of land on the east side of 20th Street from the Starrs for $27,500. The remaining portion of the campus was purchased from other descendants of William Logan Fisher.[29]

In 1956, S. Logan Wister Starr and her husband Daniel Blain inherited the mansion from Logan's parents, they kept the property a fully functioning and self-sufficient farm, despite spending most of their time in Nova Scotia. Under the Blains, in 1966, the property was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Having rented 'The Mansion' and another house, 'Shaw Manor', from the Blains since the early 1960s for dormitory space, La Salle purchased both houses in 1968, and demolished them for parking space.[26] In 1979, Logan Blain died, and her son, Daniel Blain, Jr. sold the remainder of the estate to La Salle University, in 1984.[30]

La Salle began a renovation of the estate after purchasing it, converting it from a farm into a park-like area. Several structures were demolished, including Peale's stable and hen house, which were leveled to construct tennis courts. The main house of Belfield, now called 'Peale House', was also converted to its present role as the office for the President of La Salle, while the former tenant house on the south end of the property was used for Japanese tea ceremonies from the 1980s until 2007.[26]

Gallery

-

The Wister's carriage house and Peale House.

-

The Gatehouse on the Belfield Estate.

-

A view looking west from the meadow.

-

A view looking south along 20th street at the retaining wall.

-

Another view along 20th Street.

References

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-01-23.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Charles Willson Peale House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ↑ Richard E. Greenwood (November 12, 1974). National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Belfield / Charles Willson Peale House, "Belfield" PDF (32 KB). National Park Service and Accompanying 2 photos, exterior, from 1964 PDF (32 KB)

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 1

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 2

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 3

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 9

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 11

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 13

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 20

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 21

- ↑ Wistar & Rudnytzky 2009, p. 5

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 22

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 34-36

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 28

- ↑ Wistar & Rudnytzky 2009, p. 13

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 45

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 29

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Butler 2009, p. 30

- ↑ Wistar & Rudnytzky 2009, p. 16

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 30-31

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 42

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 43

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 51-52

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 63

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Butler, James A. "Home Where 'The Mansion' Was". La Salle: A Quarterly La Salle University Magazine, Spring 1994.

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 64-66

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 67

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 69

- ↑ Butler 2009, p. 70-75

Sources

- Butler, James A. (2009). Charles Willson Peale's "Belfield":A History of a National Historic Landmark, 1684-1984. Philadelphia: La Salle University Art Museum.

- Wistar, Caroline; Rudnytzky, Kateryna A. (2009). Charles Willson Peale at Belfield: A Guide to the Historic Farm. Philadelphia: La Salle University Art Museum.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Belfield Estate. |

- Belfield and Wakefield: A Link to La Salle's Past

- Special Collections at La Salle University's Connelly Library

- Owen Wister Family Collection

- The Germantown History Collection

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. PA-1676, "Charles Willson Peale House"

- Samuel W. Pennypacker (1883). "Samuel Richardson". Historical and biographical sketches. Background on an early owner. At Wikisource.

| |||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||