Beaubassin

Coordinates: 45°50′56.86″N 64°15′39.31″W / 45.8491278°N 64.2609194°W

Beaubassin was the first settlement on the Isthmus of Chignecto, Nova Scotia, which was Acadian and once served as the capital of the colony (1678-1684). The area is now known as the Tantramar Marshes. Beaubassin was settled in 1672, the second Acadian village to be established after Port Royal. The village was one of the largest and most prosperous in Acadia. The Beaubassin area included Weskak (Westcock), Pre des Bourgs (Sackville), Pre des Richards (Middle Sackville), La Butte, Le Coupe and Le Lac (Aulac) at the confluence of the Missiguash River, Menouie and Eleysian Fields, Maccan (Makon), Nappan (Nepane) and Riviere Hebert.

During Father Le Loutre's War, Beaubassin was destroyed as part of the Acadian Exodus from mainland Nova Scotia. Its residents were resettled to the west side of the Missaquash River and the protection of Fort Beauséjour.

The site of Beaubassin was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 2005.[1] The site includes the separately designated Fort Lawrence National Historic Site.[2]

Origins

Acadians, led by a surgeon called Jacques Bourgeois, founded the village of Beaubassin in 1672.

Michel Leneuf de la Vallière de Beaubassin (d. 1705) (1640–1705, the elder) was in the French Navy. In 1676, Beaubassin and Sieur Richard Denys (his brother-in-law, the son of Nicholas Denys) as second in command, seized three English vessels from Boston that were taking on coal at Cape Breton. As a result of his success, Frontenac granted him a large piece of land at the Isthmus of Chignecto which became known as the Beaubassin seigneury (1684).

By 1685, there were 22 houses in Beaubassin. In 1686, the area was constituted into a parish and Father Claude Trouvé,[3] of Quebec, built Beaubassin's first church. The parish church was located on the site of the present day monument to Fort Lawrence, and the railroad crosses the church cemetery.

Raid in 1696

During King William's War French and Native raids on Maine, specifically on Pemaquid, Maine (present day Bristol, Maine) earlier that year. In response, the English colonial militia leader Benjamin Church led a devastating raid on Beaubassin in 1696.[4]

Church and four hundred men (50 to 150 of whom were Indians, likely Iroquois) arrived offshore of Beaubassin on September 20. They managed to get ashore and surprise the Acadian. Many fled while one confronted Church with papers showing they had signed an oath of allegiance in 1690 to the English king.

Church was unconvinced. He burned a number of buildings, killed inhabitants, looted their household goods, and slaugthered their livestock. Governor Villebon reported that "the English stayed at Beaubassin nine whole days without drawing any supplies from their vessels, and even those settlers to whom they had shown a pretence of mercy were left with empty houses and barns and nothing else except the clothes on their backs."[4]

Raid in 1704

In Queen Anne's War, Church returned to Acadia, raiding Beaubassin and other Acadian communities on the Bay of Fundy. The raid was in response to a French Raid on Deerfield earlier in 1704. This assault was actually the work of a Quebec led company of Abenaki, Kanienkehaka, Wyandot, and Pocumtuck along with some Frenchmen, 200 to 300 attackers in all. According to Faragher, the Massachusetts authorities knew that the Acadians had nothing to do with the attack,[5] but since the Acadians were closer than the French in Quebec the Acadians became the undeserving object of their revenge. As far as the New Englanders were concerned Acadians and French were synonymous, which was unfortunate for them.[6] Church also raided a French settlement near present-day Castine, Maine, Grand Pre, and Pisiguit.

De Ramezay Expedition (1747)

In preparation for the attack on the Acadian capital of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, De Ramezay arrived from Quebec and gathered forces at Beaubassin. He eventually retreated from the capital because the Duc d'Anville Expedition failed to arrive. De Ramesay again stationed himself at Beaubassin. In response to the threat of the Duc d'Anville Expedition, Massachusetts Governor William Shirley sent Colonel Arthur Noble and hundreds of New England soldiers to occupy Acadia and remove De Ramezay. One of the most startling successes of De Ramezay's campaign was the attack on a superior force of Colonel Arthur Noble's militia in the Battle of Grand Pre.

Father Le Loutre's War

Beaubassin was located near what became the de facto dividing line between French Acadia and the British province of Nova Scotia. The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, in which France ceded Acadia to Britain, did not specify boundaries, and France claimed that only the peninsular portion of Acadia had been ceded. As a result, when the British established Fort Lawrence during Father Le Loutre's War on the ruins of Beaubassin, the French countered by establishing Fort Beauséjour on the opposite side of the boundary on what is now called the Aulac Ridge.

As a result of the British threat, Le Loutre had Beaubassin burned.[7] In total there were 42 Acadian buildings burned. Upon leaving Beaubassin defeated, Lawrence arrived at Piziquid and built Fort Edward (Nova Scotia), having the Acadians destroy their church and replace it with the British fort.[8] Lawrence eventually returned to the area of Beaubassin, to build Fort Lawrence.

At Pisiguit there was little resistance to building Fort Edward. However, at Beaubassin Charles Lawrence faced resistance to building Fort Lawrence. Along with initially burning the village, upon Lawrence's return, Mi'kmaq and Acadians were dug in at Beaubassin trying to defend the remains of the village. Again Le Loutre was joined by Acadian militia leader Joseph Broussard. They were eventually overwhelmed by force and the New Englanders proceeded to erect Fort Lawrence at Beaubassin.

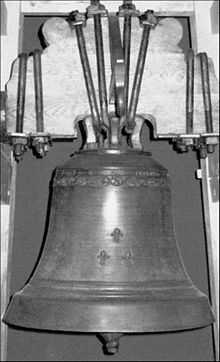

Le Loutre saved the bell from Notre Dame d'Assumption Church in Beaubassin and put it into the cathedral he had built beside Fort Beausejour (1753–55).

There is a stone marker near the Nova Scotia visitor centre off the Trans-Canada Highway in Amherst, Nova Scotia commemorating the village's existence.

References

- ↑ Beaubassin. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Fort Lawrence. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ http://www.biographi.ca/EN/009004-119.01-e.php?id_nbr=1133

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Reid, John (1998). "1686-1720: Imperial Intrusions" In The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. Toronto University Press. p. 83.

- ↑ Faragher, A Great and Noble Scheme, 109.

- ↑ The Nova Scotia Genealogist, Spring, 2009, Vol. XXVII/1, Page 16

- ↑ The practice of burning one's own residences for military ends was not uncommon. For example, at this same time Le Loutre burned Beaubassin for military reasons, French officer Boishebert burned the French Fort Menagoueche on the Saint John River to prevent it from falling in the hands of the British and to allow Acaadins to escape to the forest (see John Grenier. The Edge of Empire. Oklahoma Press. 2008. p. 179). As well, the British burned their military officers own residents at Annapolis Royal to help defeat the French, MI'kmaq and Acadian attacks during King Georges War. (See Brenda Dunn. Port Royal/ Annapolis Royal. 2004. Nimbus Press).

- ↑ See Stephan Bujold (2004). L'Acadie vers 1550: Essai de chronologie des paroisses acadiennes du bassin des Mines (Minas Basin, NS) avant le Grand derangement. SCHEC Etudes d'histoire religieuse, 70 (2004), 59-79.

Bibliography

- N.E.S. Griffiths. 2005. Migrant to Acadian, McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Benjamin Church, Thomas Church, Samuel Gardner Drake. The history of King Philip's war ; also of expeditions against the French and Indians in its Eastern parts of New England, in the years 1689, 1692, i696 AND 1704. With some account of the divine providence towards Col. Benjamin Church.

External links

- Acadians at Beaubassin

- History of Nova Scotia: Chapter 10 - "Acadia (1654-1684)"

- Parks Canada: History Beneath the Ruins of Beaubassin

| ||||||||||||||