Battle off Ulsan

| Battle off Ulsan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russo-Japanese War | |||||||

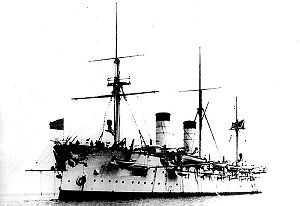

Sinking of the Russian cruiser Rurik in the Battle off Ulsan, 1904, from a contemporary propaganda postcard |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4 Armored cruisers, 2 protected cruisers | 3 Armored cruisers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Minimal casualties 1 cruiser slightly damaged | Heavy casualties 1 cruiser destroyed, two cruisers with medium damage |

||||||

The naval Battle off Ulsan (Japanese: 蔚山沖海戦 Urusan'oki kaisen; Russian: Бой в Корейском проливе, Boi v Koreiskom prolive), also known as the Battle of the Japanese Sea or Battle of the Korean Strait, took place on 14 August 1904 between cruiser squadrons of the Imperial Russian Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy during the Russo-Japanese War, four days after the Battle of the Yellow Sea.

Background

At the start of the Russo-Japanese War, the bulk of the Russian Pacific Fleet was blockaded within the confines of Port Arthur by the Imperial Japanese Navy. However, the Russian subsidiary naval base at Vladivostok, although shelled by a Japanese squadron under the command of Vice Admiral Dewa Shigeto in March 1904, remained largely undamaged. Located at Vladivostok was a garrison force consisting of the light cruiser Bogatyr and auxiliary cruiser Lena and a stronger Vladivostok Independent Cruiser Squadron consisting of the armored cruisers Rossia, Rurik, and Gromoboi. This force was under the command of Rear Admiral Karl Jessen from 15 March – 12 June 1904, Vice Admiral Petr Bezobrazov from 12 June – 16 October 1904 and from Jessen again from 15 October 1904 until the end of the war. [1]

Commerce raiding operations

The Vladivostok Independent Cruiser Squadron made a total of six sorties from Vladivostok for commerce raiding in 1904, sinking a total of 15 transports. [1] The first raid was from 9-14 February along the coast of Japan, in which a single transport was sunk. The second was from 24 February – 1 March along the coast of Korea without any results. However, during the third raid from 23-27 April, the Russian squadron ambushed Japanese troop transports approaching Gensan in Korea, causing considerable damaged. The fourth raid from 12-19 June sank several transports in the Tsushima Strait in what was called the "Hitachi Maru Incident", and resulted in the capture of a British transport, Allantown. This was followed by the fifth raid from 28 June – 3 July, again in the Tsushima Strait, in which the British transport Cheltenham was captured. Finally on 17 July-1 August, the Russian squadron raided the Pacific coast of Japan, sinking one British and one German freighter. [2] As a result of these operations, the Japanese were forced to assign the IJN 2nd Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Kamimura Hikonojō with considerable resources in an attempt to locate and destroy the Russian squadron. Kamimura’s failure to do so on several occasions created considerable adverse public comment in Japan.

Sortie

A telegram from the First Pacific Squadron at Port Arthur reached Vladivostok on the afternoon of 11 August 1904, stating that Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft had decided to attempt to break through the Japanese blockade, and therefore Vice Admiral Jessen was ordered to sortie the Vladivostok Cruiser Squadron to assist. However, as late as 5 August 1904, a telegram had been received from Vitgeft stating his intention to perish with Port Arthur, so the Vladivostok cruisers took time to get ready for action. Owing to the delay in sailing, there was little hope of being able to assist the First Pacific Squadron at the critical passage of the Tsushima Straits; however on the assumption that Vitgeft would be successful, the two squadrons planned to rendezvous in the Sea of Japan.

The warships of the Vladivostok Cruiser Squadron formed in a line abreast at intervals of four nautical miles (7 km) and headed southward at 14 knots (26 km/h), in hourly expectation of sighting the Port Arthur Squadron. However, the Port Arthur Squadron had not been sighted by the following morning. As the Vladivostok Cruiser Squadron approached Busan, Jessen advised his captains that he had no intention of attempting to pass Tsushima Straits, and ordered the squadron back to Vladivostok.

The Japanese 2nd Fleet under Admiral Kamiyama was made up of four armored cruisers Izumo, Azuma, Tokiwa, Iwate, and two protected cruisers Naniwa and Takachiho . The Japanese squadron had passed very close to the Russian squadron in the dark of the previous night on opposite courses but neither was aware of the other.

From 01:30 on14 August 1904, Kamimura had been heading back from his night patrol area on a course that took him directly to the Russian squadron. When Yessen started his turn back to Vladivostock, he sighted the four Japanese armored cruisers.

The situation was ideal for the Japanese side. It was dawn on a fine summer day, and the enemy was as far from Vladivostok as it was possible to be in the Sea of Japan, with the Japanese squadron between themselves and their distant base.

The battle

At 0520 on 14 August 1904 the fleets had closed to 7,800 metres (25,600 ft), and the Japanese opened fire first. For unknown reasons, Kamimura, ordered fire concentrated on the Rurik, the last and weakest in the Russian column. Subjected to twice the bombardment administered to her stronger comrades, Rurik lost most of her officers in a short time, and although extremely damaged, remained afloat, the diminishing number of survivors continuing to fire the few remaining guns until the very last, in a gallant display of classic heroism that won the admiration of the Japanese.

On the easterly run the Japanese ships took some hits, but nothing comparable to what they inflicted. It was assumed that when the Russians sheered away, Kamimura would have pressed his advantage closer. Inexplicably, this did not happen. Kamimura oddly held his course during the Russian turn, and when he ordered his forces to turn a few minutes later, it was to a new tack that actually lengthened rather than narrowed the range.

The remaining Russian cruisers tried to cover the Rurik, but with increasing damage, Jessen decided at 08:30 to scuttle the Rurik, and save his other ships by heading back towards Vladivostok. The Japanese cruisers pursued for some time, and firing continued, with more damage to the Russian cruisers and slight damage to the Iwate and the Azuma. The Russians were in a far worse condition than the Japanese, but Kamimura then made another controversial decision: after pursuit of only three hours, while still on the high seas, and with long daylight steaming hours between the Japanese cruisers and Vladivostok, at 11:15 hours he broke off the chase, and turned back towards Busan.

Despite Kamimura's failure to destroy the two remaining Russian cruisers, he was hailed as a hero in Japan. Although two of the three Russian cruisers escaped, their damage was greater than what the limited repair facilities at Vladivostok could handle, and the Vladivostok Cruiser Squadron never threatened Japanese shipping again.

Russian point of view

From the Imperial Russian Navy's point of view, the Rurik was scuttled by her own crew, not by Admiral Jessen's decision. The Rurik was hit by a shell in her unarmored stern and the steering mechanism was destroyed, immobilizing her rudder in an elevated position. So the maximum speed of Rurik had been greatly reduced and her steering had to be performed by reducing the revolutions of each one of her propellers. Jessen successfully diverted all four Japanese armored cruisers and hoped that Rurik could withstand against the Naniwa and Takachiho. However, the condition of Rurik was rather bad. First Rank Captain Trusov, her commander, and all senior officers were killed. Finally, Lieutenant Ivanov (the thirteenth in command) ordered the Rurik to be scuttled.

The Russia and Gromoboi successfully repelled the attack of Kamimura's cruisers at the price of sustaining heavy damage, but IRN sailors, while still under fire, were able to repair the main 203 mm (8 inch) guns and continue to engage with them. Faced with an increasing rate of fire from the Russian cruisers and with his ammunition supplies nearly depleted, Admiral Kamimura decided to stop pursuit.

The very heavy Russian casualties suffered in the battle were the result of two factors: the bursting charges in Japanese shells was picric acid (trinitrophenol) which on detonation turned the shells into very large numbers of fragments. Additionally the Russian ships lacked protective gun shields for the crews.

Order of battle

- Ship order is according to their position in line

Russia[3]

Vladivostok Cruiser Force - Rear Admiral Karl Jessen:

- Armoured cruisers:

Japan[4]

2nd Fleet - Vice Admiral Kamimura Hikonojō

- 2nd Unit: armored cruisers:

- 4th Unit: protected cruisers:

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War, p. 412.

- ↑ Westwood, Russia Against Japan, p. 90.

- ↑ S.Suliga (С. Сулига): Korabli Russko-Yaponskoy voyny. Chast 1. Rossiyskiy flot (Корабли Русско – Японской войны. Часть 1. Российский флот), Arsenal

- ↑ S.Suliga (С. Сулига): Korabli Russko-Yaponskoy voyny. Chast 2. Yaponskiy flot (Корабли Русско – Японской войны. Часть 2. Японский флот), Arsenal

Sources

- Brook, Peter, Armoured Cruiser versus Armoured Cruiser, Ulsan, 14 August 1904, in Warship 2000-2001, Conway's Maritime Press, ISBN 0-85177-791-0

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5: The Scarecrow Press.

- Westwood, J.N. (1986). Russia Against Japan, 1904-1905: A New Look at the Russo-Japanese War. ISBN 0887061915: State University of New York Press.

- Warner, Denis and Peggy (1974). The Tide at Sunrise: A History of the Russo-Japanese War', 1904-1905. New York.

- Мельников Р. М. «Рюрик» был первым. — Л.: Судостроение, 1989. (Melnikov R. M. The Rurik was first, Leningrad, Sudostroenie Publishing Company, 1989)