Baryogenesis

| Why does the observable universe have more matter than antimatter? |

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

|

Early universe

|

|

Expanding universe |

|

Structure formation

|

|

Future of universe |

|

Components |

|

Social impact |

|

In physical cosmology, baryogenesis is the generic term for hypothetical physical processes that produced an asymmetry between baryons and antibaryons in the very early universe, resulting in the substantial amounts of residual matter that make up the universe today.

Baryogenesis theories (the most important being electroweak baryogenesis and GUT baryogenesis) employ sub-disciplines of physics such as quantum field theory, and statistical physics, to describe such possible mechanisms. The fundamental difference between baryogenesis theories is the description of the interactions between fundamental particles.

The next step after baryogenesis is the much better understood Big Bang nucleosynthesis, during which light atomic nuclei began to form.

Background

The Dirac equation,[1] formulated by Paul Dirac around 1928 as part of the development of relativistic quantum mechanics, predicts the existence of antiparticles along with the expected solutions for the corresponding particles. Since that time, it has been verified experimentally that every known kind of particle has a corresponding antiparticle. The CPT Theorem guarantees that a particle and its antiparticle have exactly the same mass and lifetime, and exactly opposite charge. Given this symmetry, it is puzzling that the universe does not have equal amounts of matter and antimatter. Indeed, there is no experimental evidence that there are any significant concentrations of antimatter in the observable universe.

There are two main interpretations for this disparity: either the universe began with a small preference for matter (total baryonic number of the universe different from zero), or the universe was originally perfectly symmetric, but somehow a set of phenomena contributed to a small imbalance in favour of matter over time. The second point of view is preferred, although there is no clear experimental evidence indicating either of them to be the correct one.

Sakharov conditions

In 1967, Andrei Sakharov proposed[2] a set of three necessary conditions that a baryon-generating interaction must satisfy to produce matter and antimatter at different rates. These conditions were inspired by the recent discoveries of the cosmic background radiation [3] and CP-violation in the neutral kaon system. [4] The three necessary "Sakharov conditions" are:

- Baryon number

violation.

violation. - C-symmetry and CP-symmetry violation.

- Interactions out of thermal equilibrium.

Baryon number violation is obviously a necessary condition to produce an excess of baryons over anti-baryons. But C-symmetry violation is also needed so that the interactions which produce more baryons than anti-baryons will not be counterbalanced by interactions which produce more anti-baryons than baryons. CP-symmetry violation is similarly required because otherwise equal numbers of left-handed baryons and right-handed anti-baryons would be produced, as well as equal numbers of left-handed anti-baryons and right-handed baryons. Finally, the interactions must be out of thermal equilibrium, since otherwise CPT symmetry would assure compensation between processes increasing and decreasing the baryon number.[5]

Currently, there is no experimental evidence of particle interactions where the conservation of baryon number is broken perturbatively: this would appear to suggest that all observed particle reactions have equal baryon number before and after. Mathematically, the commutator of the baryon number quantum operator with the (perturbative) Standard Model hamiltonian is zero:

![[B,H]=BH-HB=0](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/f/2/2/f/f22f8e550041d04941acccc2453107ce.png) . However, the Standard Model is known to violate the conservation of baryon number non-perturbatively: a global U(1) anomaly.

Baryon number violation can also result from physics beyond the Standard Model (see supersymmetry and Grand Unification Theories).

. However, the Standard Model is known to violate the conservation of baryon number non-perturbatively: a global U(1) anomaly.

Baryon number violation can also result from physics beyond the Standard Model (see supersymmetry and Grand Unification Theories).

The second condition – violation of CP-symmetry – was discovered in 1964 (direct CP-violation, that is violation of CP-symmetry in a decay process, was discovered later, in 1999). Due to CPT-symmetry, violation of CP-symmetry demands violation of time inversion symmetry, or T-symmetry.

In the out-of-equilibrium decay scenario,[6] the last condition states that the rate of a reaction which generates baryon-asymmetry must be less than the rate of expansion of the universe. In this situation the particles and their corresponding antiparticles do not achieve thermal equilibrium due to rapid expansion decreasing the occurrence of pair-annihilation.

Baryogenesis within the Standard Model

The Standard Model can incorporate baryogenesis, though the amount of net baryons (and leptons) thus created may not be sufficient to account for the present baryon asymmetry; this issue has not yet been determined decisively.

Baryogenesis within the Standard Model requires the electroweak symmetry breaking be a first-order phase transition, since otherwise sphalerons wipe off any baryon asymmetry that happened up to the phase transition, while later the amount of baryon non-conserving interactions is negligible.[7]

The phase transition domain wall breaks the P-symmetry spontaneously, allowing for CP-symmetry violating interactions to create C-asymmetry on both its sides: quarks tend to accumulate on the broken phase side of the domain wall, while anti-quarks tend to accumulate on its unbroken phase side. This happens as follows:[5]

Due to CP-symmetry violating electroweak interactions, some amplitudes involving quarks are not equal to the corresponding amplitudes involving anti-quarks, but rather have opposite phase (see CKM matrix and Kaon); since time reversal takes an amplitude to its complex conjugate, CPT-symmetry is conserved.

Though some of their amplitudes have opposite phases, both quarks and anti-quarks have positive energy, and hence acquire the same phase as they move in space-time. This phase also depends on their mass, which is identical but depends both on flavor and on the Higgs VEV which changes along the domain wall. Thus certain sums of amplitudes for quarks have different absolute values compared to those of anti-quarks. In all, quarks and anti-quarks may have different reflection and transmission probabilities through the domain wall, and it turns out that more quarks coming from the unbroken phase are transmitted compared to anti-quarks.

Thus there is a net baryonic flux through the domain wall. Due to sphaleron transitions, which are abundant in the unbroken phase, the net anti-baryonic content of the unbroken phase is wiped off. However, sphalerons are rare enough in the broken phase as not to wipe off the excess of baryons there. In total, there is net creation of baryons.

In this scenario, non-perturbative electroweak interactions (i.e. the sphaleron) are responsible for the B-violation, the perturbative electroweak Lagrangian is responsible for the CP-violation, and the domain wall is responsible for the lack of thermal equilibrium; together with the CP-violation it also creates a C-violation in each of its sides.

Matter content in the universe

Baryon asymmetry parameter

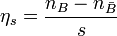

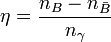

The challenges to the physics theories are then to explain how to produce this preference of matter over antimatter, and also the magnitude of this asymmetry. An important quantifier is the asymmetry parameter,

.

.

This quantity relates the overall number density difference between baryons and antibaryons (nB and nB, respectively) and the number density of cosmic background radiation photons nγ.

According to the Big Bang model, matter decoupled from the cosmic background radiation (CBR) at a temperature of roughly 3,000 kelvin, corresponding to an average kinetic energy of 3,000 K / (10.08×103 K/eV) = 0.3 eV. After the decoupling, the total number of CBR photons remains constant. Therefore due to space-time expansion, the photon density decreases. The photon density at equilibrium temperature T per cubic centimeter, is given by

,

,

with kB as the Boltzmann constant, ħ as the Planck constant divided by 2π and c as the speed of light in vacuum. At the current CBR photon temperature of 2.725 K, this corresponds to a photon density nγ of around 411 CBR photons per cubic centimeter.

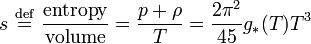

Therefore, the asymmetry parameter η, as defined above, is not the "good" parameter. Instead, the preferred asymmetry parameter uses the entropy density s,

because the entropy density of the universe remained reasonably constant throughout most of its evolution. The entropy density is

with p and ρ as the pressure and density from the energy density tensor Tμν, and g* as the effective number of degrees of freedom for "massless" particles (inasmuch as mc2 ≪ kBT holds) at temperature T,

,

,

for bosons and fermions with gi and gj degrees of freedom at temperatures Ti and Tj respectively. At the present era, s = 7.04nγ.

See also

- Lepton

- Leptogenesis

- CP violation

- Anthropic principle

- Affleck-Dine mechanism

- Timeline of the Big Bang

- Chronology of the universe

- Big Bang

References

Articles

- ↑ P.A.M. Dirac (1928). "The Quantum Theory of the Electron". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A 117 (778): 610–624. Bibcode:1928RSPSA.117..610D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1928.0023.

- ↑ A. D. Sakharov (1967). "Violation of CP invariance, C asymmetry, and baryon asymmetry of the universe". Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics 5: 24–27., republished as A. D. Sakharov (1991). "Violation of CP invariance, C asymmetry, and baryon asymmetry of the universe". Soviet Physics Uspekhi 34 (5): 392–393. Bibcode:1991SvPhU..34..392S. doi:10.1070/PU1991v034n05ABEH002497.

- ↑ A. A. Penzias and R. W. Wilson (1965). "A Measurement of Excess Antenna Temperature at 4080 Mc/s". Astrophysical Journal 142: 419–421. Bibcode:1965ApJ...142..419P. doi:10.1086/148307.

- ↑ J. W. Cronin, V. L. Fitch et al. (1964). "Evidence for the 2π decay of the K0

2 meson". Physical Review Letters 13 (4): 138–140. Bibcode:1964PhRvL..13..138C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.138. - ↑ 5.0 5.1 M. E. Shaposhnikov, G. R. Farrar (1993). "Baryon Asymmetry of the Universe in the Minimal Standard Model". Physical Review Letters 70 (19): 2833–2836. arXiv:hep-ph/9305274. Bibcode:1993PhRvL..70.2833F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.2833.

- ↑ A. Riotto, M. Trodden (1999). "Recent progress in baryogenesis". Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 49: 46. arXiv:hep-ph/9901362. Bibcode:1999ARNPS..49...35R. doi:10.1146/annurev.nucl.49.1.35.

- ↑ V. A. Kuzmin, V. A. Rubakov, M. E. Shaposhnikov (1985). "On anomalous electroweak baryon-number non-conservation in the early universe". Physic Letters B 155: 36–42. Bibcode:1985PhLB..155...36K. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(85)91028-7.

Textbooks

- E. W. Kolb and M. S. Turner (1994). The Early Universe. Perseus Publishing. ISBN 0-201-62674-8.

Preprints

- A. D. Dolgov (1997). "Baryogenesis, 30 Years After". arXiv:hep-ph/9707419 [hep-ph].

- A. Riotto (1998). "Theories of Baryogenesis". arXiv:hep-ph/9807454 [hep-ph/9807454].

- M. Trodden (1998). "Electroweak Baryogenesis". Reviews of Modern Physics 71 (5): 1463. arXiv:hep-ph/9803479. Bibcode:1999RvMP...71.1463T. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.71.1463.