Baibars

| Baibars | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Reign | 24 October 1260 – 1 July 1277 |

| Coronation | 1260 at Salihiyah |

| Predecessor | Qutuz |

| Successor | Al-Said Barakah |

| Spouse | Several |

| Issue | |

| al-Said Barakah Solamish | |

| Full name | |

| al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baibars al-Bunduqdari Abu al-Futuh | |

| Dynasty | Bahri |

| Born | 19 July 1223 Crimea |

| Died | 1 July 1277 (aged 54) Damascus, Syria |

| Religion | Islam |

Baibars or Baybars (Arabic: الملك الظاهر ركن الدين بيبرس البندقداري, al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baibars al-Bunduqdari), nicknamed Abu l-Futuh[1] (Arabic: أبو الفتوح) (1223 – 1 July 1277) was the fourth Sultan of Egypt from the Mamluk Bahri dynasty. He was one of the commanders of the Egyptian forces that inflicted a devastating defeat on the Seventh Crusade of King Louis IX of France. He also led the vanguard of the Egyptian army at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260,[2] which marked the second substantial defeat of the Mongol army, and is considered a turning point in history.[3] Baibars' reign marked the start of an age of Mamluk dominance in the Eastern Mediterranean, and solidified the durability of their military system. He managed to pave the way for the end of the Crusader presence in the Levant, and reinforced the union of Egypt and Syria as the region's pre-eminent Arab and Muslim state, able to fend off threats from both Crusaders and Mongols. As Sultan, Baibars also engaged in a combination of diplomacy and military action, which allowed the Mamluks of Egypt to greatly expand their empire.

Biography

Early life

Born in the Dasht-I-Kipchak modern day Kazakhstan, between rivers of Edil (Volga) and Yaiyk (Ural), Baibars was a Turkic Kipchak/Cuman (from Berish tribe, that currently lives in Kazakhstan).[4][5][6][7][8][9] He was fair-skinned, blond,[10] very tall and had a cataract in one of his bluish eyes. It was said that he was captured by the Mongols[citation needed] in the Kipchak steppe and sold as a slave, and subsequently travelling to the Second Bulgarian Empire and the Near East, [11] eventually ending up in Syria.

Baibars was quickly sold to a Mamluk officer called Aydekin al bondouqdar, and sent to Egypt, where he became a bodyguard to the Ayyubid ruler As-Salih Ayyub.

Rise to power

Baibars was a commander of the Mamluks in around 1250, when he defeated the Seventh Crusade of Louis IX of France. He was still a commander under Sultan Qutuz at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, when he decisively defeated the Mongols. After the battle, Sultan Qutuz (aka Koetoez) was assassinated while on a hunting expedition. It was said that Baibars was involved in the assassination because he expected to be rewarded with the governorship of Aleppo for his military success; but Qutuz, fearing his ambition, refused to give such a post and disappointed him.[12] Baibars succeeded Qutuz as Sultan of Egypt.[13]

Sultan of Egypt

He continued what was to become a lifelong struggle against the Crusader kingdoms in Syria, starting with the Principality of Antioch, which had become a vassal state of the Mongols, and participated in attacks against Islamic targets in Damascus and Syria.

In 1263, Baibars attacked Acre, the capital of the remnant of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, but was unable to take it. Nevertheless, he defeated the Crusaders in many other battles (Arsuf, Athlith, Haifa, Safad, Jaffa, Ashkalon, Caesarea).

In 1266 Baibars invaded the Christian country of Cilician Armenia, which, under King Hethum I, had submitted to the Mongol Empire. This isolated Antioch and Tripoli, led by Hetum's son-in-law, Prince Bohemond VI. In 1268, Baibars besieged Antioch, capturing the city on 18 May. Baibars had promised to spare the lives of the inhabitants, but broke his promise and had the city razed, killing or enslaving the population upon surrender.[14] This tactic was common in Baibars' campaigns, and was largely responsible for the swiftness of his victories.[citation needed]

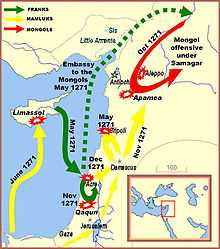

Baibars then turned his attention to Tripoli, but interrupted his siege there to call a truce in May 1271. The fall of Antioch had led to the brief Ninth Crusade, led by Prince Edward of England, who arrived in Acre in May 1271 and attempted to ally with the Mongols against Baibars. So Baibars declared a truce with Tripoli, as well as with Edward (who was never able to capture any territory from Baibars anyway). According to some reports, Baibars tried to have Edward assassinated with poison, but Edward survived the attempt, and returned home in 1272.

In 1277, Baibars invaded the Seljuq Sultanate of Rûm, then dominated by the Mongols. He defeated a Mongol army at the Battle of Elbistan, captured the city of Kayseri, but was unable to hold any of his Anatolian conquests and quickly withdrew to Syria.

Death

Baibars died in Damascus on 1 July 1277. His demise has been the subject of some academic speculation. Many sources agree that he died from drinking poisoned kumis that was intended for someone else. Other accounts suggest that he may have died from a wound while campaigning, or from illness.[15] He was buried in the Az-Zahiriyah Library in Damascus.[16]

Family

Baibars married several women and had seven daughters and three sons. Two of his sons, al-Said Barakah and Solamish, became sultans.

Assessment

As the first Sultan of the Bahri Mamluk dynasty, Baibars made the meritocratic ascent up the ranks of Mamluk society. He took final control after the assassination of Sultan Sayf al Din Qutuz, but before he became Sultan he was the commander of the Mamluk forces in the most important battle of the Middle Periods, repelling a Mongol force at the legendary Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260.[17] Although in the Muslim World he has been considered a national hero for centuries, and in Egypt, Syria and Kazakhstan is still regarded as such, Sultan Baibars was reviled in the Christian world of the time for his seemingly unending victorious campaigns. A Templar knight who fought in the Seventh Crusade lamented:

Rage and sorrow are seated in my heart...so firmly that I scarce dare to stay alive. It seems that God wishes to support the Turks to our loss...ah, lord God...alas, the realm of the East has lost so much that it will never be able to rise up again. They will make a Mosque of Holy Mary's convent, and since the theft pleases her Son, who should weep at this, we are forced to comply as well...Anyone who wishes to fight the Turks is mad, for Jesus Christ does not fight them any more. They have conquered, they will conquer. For every day they drive us down, knowing that God, who was awake, sleeps now, and Muhammad waxes powerful.[18]

Baibars also played an important role in bringing the Mongols to Islam. He developed strong ties with the Mongols of the Golden Horde and took steps for the Golden Horde Mongols to travel to Egypt. The arrival of the Golden Horde Mongols to Egypt resulted in a significant number of Mongols accepting Islam.[19]

Legacy

Baibars was a popular ruler in the Muslim World who had defeated the crusaders in three campaigns, and the Mongols in the Battle of Ain Jalut which many scholars deem of great macro-historical importance. In order to support his military campaigns, Baibars commissioned arsenals, warships and cargo vessels. He was also arguably the first to employ explosive hand cannons in war, at the Battle of Ain Jalut.[20][21] His military campaign also extended into Libya and Nubia.

He was also an efficient administrator who took interest in building various infrastructure projects, such as a mounted message relay system capable of delivery from Cairo to Damascus in four days. He also built bridges, irrigation and shipping canals, improved the harbours, and built mosques. He was also a patron of Islamic science, such as his support for the medical research by his Arab physician, Ibn al-Nafis.[22] As a testament of a special relationship between Islam and cats, Baibars left a cat garden in Cairo as a waqf, providing the cats of Cairo with food and shelter.[23]

His memoirs were recorded in Sirat al-Zahir Baibars ("Life of al-Zahir Baibars"), a popular Arabic romance recording his battles and achievements. He has a heroic status in Kazakhstan, as well as in Egypt and Syria.

Al-Madrassa al-Zahiriyya is the school built adjacent to his Mausoleum in Damascus. The Az-Zahiriyah library, has a wealth of manuscripts in various branches of knowledge to this day. The library and Mausoleum are being reconstructed by Kazakhstan government fund.

Presently the Minister of Culture and Information of Kazakhstan Mukhtar Kul-Mukhammed said that within the realization of Cultural Heritage Kazakh Strategic Project for 2009–2011 Astana have launched reconstruction of the Sultan Beibars Mausoleum in Damascus and his Mosque in Cairo in order to propagate Kazakhstan's national historical heritage on the international level.

In fiction

- Baibars figures prominently in the story "The Sowers of the Thunder" by Robert E. Howard. While liberties are taken with history for the sake of the tale, and many characters and events are purely imaginary, his character is fairly close to the folkloric depiction and the general flow of history is respected.

- Baibars is the main character of a novel "Yemshan" by Russian-Kazakh writer Moris Simashko (Moris Davidovich Shamas)

- Baibars is one of the main characters of Robyn Young's books, Brethren (starting shortly before he becomes Sultan) and Crusade.

- Baibars is the main character of Jefferson Cooper's (Gardner Fox) 1957 novel, The Swordsman

- According to Harold Lamb, Haroun of Baghdad in the Arabian Nights was really Baibars of Cairo.[24]

- Baibars is one of the central characters in Lebanese- American author Rabih Alameddine's The Hakawati.

- Baibars is one of the characters in the The Children of the Grail books by Peter Berling.

- Sultan Beybars – movie shot in 1989 by Kazakh National Cinema Studio "Kazakh Film" Султан Бейбарс — художественный телефильм 1989 года

- Qahira ka Qaher (A Warrior of Egypt) Real biography of Sultan, written by historian Muazam Javed Bukhari

See also

- Ninth Crusade

- Ablaq

- Bahri dynasty

- Cumania

- Cuman people

- Kipchak people

- List of rulers of Egypt

- Sirat al-Zahir Baibars

References

- ↑ Baibars was nicknamed Abu l-Futuh and Abu l-Futuhat which means Father of Conquests, pointing to his victories

- ↑ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Macropædia, H.H. Berton Publisher, 1973–1974, p.773/vol.2

- ↑ The history of the Mongol conquests, By J. J. Saunders, pg. 115

- ↑ Al-Maqrizi, Al Selouk Leme'refatt Dewall al-Melouk, p.520/vol.1

- ↑ Ibn Taghri, al-Nujum al-Zahirah Fi Milook Misr wa al-Qahirah, Year 675H /vol.7

- ↑ Abu al-Fida, The Concise History of Humanity, Tarikh Abu al-Fida pp.71-87/ year 676H

- ↑ Ibn Iyas , Badai Alzuhur Fi Wakayi Alduhur, abridged and edited by Dr. M. Aljayar, Almisriya Lilkitab, Cairo 2007, ISBN 977-419-623-6 , p.91

- ↑ Baibars in Concise Britannica Online, web page

- ↑ Brief Article in Columbia Encyclopedia, web page

- ↑ Maalouf, Amin (1984). The crusades through Arab eyes. Saqi Books. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-86356-023-1.

- ↑ “The” Other Europe in the Middle Ages: Avars, Bulgars, Khazars and Cumans, edited by Florin Curta, Roman Kovalev, pg 9

- ↑ The story of the involvement of Baibars in the assassination of Sultan Qutuz was told by different source-books historians in different ways, in one account the assassins killed Qutuz while he was giving a hand to Baibars (Al-Maqrizi and Ibn-Taghri). On another account, which is an Ayyubid source, Qutuz was giving a hand to someone when Baibars struck his back with a sword (Abu-Al-Fida). A third account mentioned that Baibars tried to help Qutuz against the assassins (O. Hassan). According to Al-Maqrizi, the Emirs who struck Qutuz were Badr ad-Din Baktut, Emir Ons and Emir Bahadir al-Mu'izzi. (Al-Maqrizi, p.519/vol.1)

- ↑ MacHenry, Robert. The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 1993. Baibars

- ↑ Hudson Institute > American Outlook > American Outlook Article Detail

- ↑ Young, Robyn (2007). Crusade. Dutton. p. 484.

- ↑ Zahiriyya Madrasa and Mausoleum of Sultan al-Zahir Baybars

- ↑ 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present By Paul K. Davis, pg. 141

- ↑ Howarth,p.223

- ↑ The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith, By Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 192

- ↑ Ahmad Y Hassan, Gunpowder Composition for Rockets and Cannon in Arabic Military Treatises In Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries

- ↑ Ancient Discoveries, Episode 12: Machines of the East, History Channel, 2007 (Part 4 and Part 5)

- ↑ Albert Z. Iskandar, "Ibn al-Nafis", in Helaine Selin (1997), Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 0-7923-4066-3.

- ↑ Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438126964.

- ↑ Lamb, Harold. The Crusades. Garden City Publishing, 1934. page 343

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baibars. |

- Baibars article from Encyclopedia of the Orient

- Baibars in Concise Britannica online

- Al-Madrassa al-Zahiriyya and Baybars Mausoleum

- Brief Article in Columbia Encyclopedia

- Extensive Arabic Article on Baybars

- Brief Biography

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Qutuz |

Mamluk Sultan 1260–1277 |

Succeeded by Al-Said Barakah |