Bézout's identity

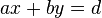

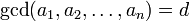

Bézout's identity (also called Bézout's lemma) is a theorem in the elementary theory of numbers: let a and b be integers, not both zero, and let d be their greatest common divisor. Then there exist integers x and y such that

In addition, i) d is the smallest positive integer that can be written as

ax + by,

and ii) every integer of the form

ax + by

is a multiple of d. x and y are called Bézout coefficients for (a, b); they are not unique. A pair of Bézout coefficients can be computed by the extended Euclidean algorithm. If both a and b are nonzero, the extended Euclidean algorithm produces one of the two pairs such that  and

and

Bézout's lemma is true in any principal ideal domain, but there are integral domains in which it is not true.

History

French mathematician Étienne Bézout (1730–1783) proved this identity for polynomials.[1] However, this statement for integers can be found already in the work of another French mathematician, Claude Gaspard Bachet de Méziriac (1581–1638).[2][3][4]

Non-uniqueness of solutions

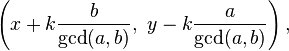

After one pair of Bézout coefficients (x, y) has been computed (using extended Euclidean algorithm or some other algorithm), all pairs have the form

where k is an arbitrary integer and the fractions simplify to integers.

Among these pairs of Bézout coefficients, exactly two of them satisfy

This relies on a property of Euclidean division: given two integers c and d, if d does not divide c, there is exactly one pair (q,r) such that c = dq + r and 0 < r < |d|, and another one such that c = dq + r and 0 < -r < |d|.

The Extended Euclidean algorithm always produces one of these two minimal pairs.

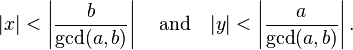

Example

Let a = 12 and b = 42, gcd(12, 42) = 6. Then we have the following Bézout's identities, with the Bézout coefficients written in red for the minimal pairs and in blue for the other ones.

Bézout's identity for several integers

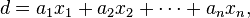

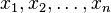

Bézout's identity can be extended to more than two integers: if

then there are integers

such that

has the following properties

- d is smallest positive integer of this form

- every number of this form is a multiple of d

- d is a greatest common divisor of a1, ..., an, meaning that every common divisor of a1, ..., an divides d

Bézout's identity for polynomials

Bézout's identity works for polynomial in one indeterminate over a field (mathematics) exactly in the same ways as for integers. In particular the Bézout's coefficients and the greatest common divisor may be computed with the Extended Euclidean algorithm.

As the common roots of two polynomials are the roots of their greatest common divisor, Bézout's identity and fundamental theorem of algebra imply the following result: Given two univariate polynomials f and g with coefficients in an field, there exist two polynomials a and b such that af + bg = 1 if and only if f and g have no common root in any algebraically closed field (commonly the field of complex numbers).

The generalization of this result to any number of polynomials and indeterminates is Hilbert's Nullstellensatz.

Bézout's identity for principal ideal domains

As noted in the introduction, Bézout's identity works not only in the ring of integers, but also in any other principal ideal domain (PID). That is, if R is a PID, and a and b are elements of R, and d is a greatest common divisor of a and b, then there are elements x and y in R such that ax + by = d. The reason: the ideal Ra+Rb is principal and indeed is equal to Rd. An integral domain in which Bézout's identity holds is called a Bézout domain.

Proof

Bézout's lemma is a consequence of the Euclidean division defining property, namely that the division by a nonzero integer b has a remainder strictly less than |b|. The proof that follows may be adapted for any Euclidean domain. For given nonzero integers a and b there is a nonzero integer d = as + bt of minimal absolute value among all those of the form ax + by with x and y integers; one can assume d > 0 by changing the signs of both s and t if necessary. Now the remainder of dividing either a or b by d is also of the form ax + by since it is obtained by subtracting a multiple of d = as + bt from a or b, and on the other hand it has to be strictly smaller in absolute value than d. This leaves 0 as only possibility for such a remainder, so d divides a and b exactly. If c is another common divisor of a and b, then c also divides as + bt = d. Since c divides d but is not equal to it, it must be less than d. This means that d is the greatest common divisor of a and b; this completes the proof.

See also

- AF+BG theorem, an analogue of Bézout's identity for homogeneous polynomials in three indeterminates

- Fundamental theorem of arithmetic

- Euclid's lemma

Notes

- ↑ Bézout, Théorie générale des équations algébriques (Paris, France: Ph.-D. Pierres, 1779).

- ↑ Tignol, Jean-Pierre (2001). Galois' Theory of Algebraic Equations. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 981-02-4541-6.

- ↑ Claude Gaspard Bachet (sieur de Méziriac) (1624). Problèmes plaisants & délectables qui se font par les nombres (2nd ed.). Lyons, France: Pierre Rigaud & Associates. pp. 18–33. On these pages, Bachet proves (without equations) “Proposition XVIII. Deux nombres premiers entre eux estant donnez, treuver le moindre multiple de chascun d’iceux, surpassant de l’unité un multiple de l’autre.” (Given two numbers [which are] relatively prime, find the lowest multiple of each of them [such that] one multiple exceeds the other by unity (1).) This problem (namely, ax - by = 1) is a special case of Bézout’s equation and was used by Bachet to solve the problems appearing on pages 199 ff.

- ↑ See also: Maarten Bullynck (February 2009). "Modular arithmetic before C.F. Gauss: Systematizations and discussions on remainder problems in 18th-century Germany". Historia Mathematica 36 (1): 48–72. doi:10.1016/j.hm.2008.08.009.

External links

- Online calculator of Bézout's identity.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Bézout's Identity", MathWorld.