Axis–angle representation

In mathematics, the axis–angle representation of a rotation parameterizes a rotation in a three-dimensional Euclidean space by two values: a unit vector  indicating the direction of an axis of rotation, and an angle θ describing the magnitude of the rotation about the axis. The rotation occurs in the sense prescribed by the right-hand rule. The rotation axis, a locus of points that do not move, is sometimes called Euler axis.

indicating the direction of an axis of rotation, and an angle θ describing the magnitude of the rotation about the axis. The rotation occurs in the sense prescribed by the right-hand rule. The rotation axis, a locus of points that do not move, is sometimes called Euler axis.

It is one of many rotation formalisms in three dimensions. These formalisms describe rotations around the origin, a fixed point. Alternatively, one can understand such rotations as transformations of vectors, not points; in other words, translations are ignored. The axis–angle representation evolves from Euler's rotation theorem, which implies that any rotation or sequence of rotations of a rigid body in a three-dimensional space is equivalent to a pure rotation about a single fixed axis.

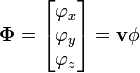

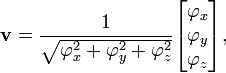

The axis–angle representation is equivalent to the more concise rotation vector, or Euler vector. In this case, both the rotation axis and the angle are represented by a Euclidean vector codirectional with the rotation axis whose magnitude is the rotation angle θ:

Uses

The axis–angle representation is convenient when dealing with rigid body dynamics. It is useful to both characterize rotations, and also for converting between different representations of rigid body motion, such as homogeneous transformations and twists.

When a rigid body rotates around a fixed axis, its axis–angle data are a constant rotation axis and the rotation angle continuously dependent on time.

Example

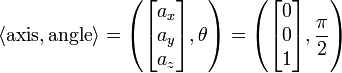

Say you are standing on the ground and you pick the direction of gravity to be the negative z direction. Then if you turn to your left, you will travel  radians (or 90°) about the z axis. In axis-angle representation, this would be

radians (or 90°) about the z axis. In axis-angle representation, this would be

Rotation vector

The above example can be represented as a rotation vector with a magnitude of  pointing in the z direction.

pointing in the z direction.

This is the product of the angle and vector. It is more compact and is used for the exponential and log maps involving this representation.

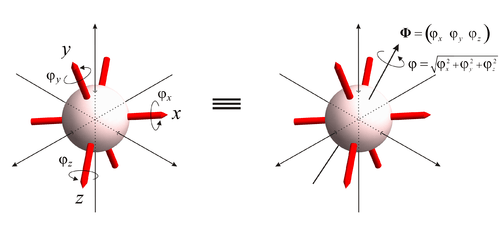

Simultaneous orthogonal rotation angle

Simultaneous Orthogonal Rotations Angle (SORA) is a vector representing angular orientation of a rigid body relative to some reference frame. The components of this vector are equal to the angles of three simultaneous rotations around the rigid body's intrinsic coordinate system axes, initially aligned with the axes of the reference frame, needed to move the rigid body to its current angular orientation.

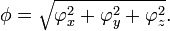

Every angular orientation can be represented by a single rotation. Therefore, the three simultaneous orthogonal rotations actually represent a single rotation around a certain axis v and for a certain angle  . The orientation and magnitude of SORA are equal to this equivalent single rotation axis v and angle

. The orientation and magnitude of SORA are equal to this equivalent single rotation axis v and angle  , respectively. SORA is therefore the rotation vector. Denoting the angles of the three simultaneous orthogonal rotations with

, respectively. SORA is therefore the rotation vector. Denoting the angles of the three simultaneous orthogonal rotations with  ,

,  , and

, and  , SORA is equal to:

, SORA is equal to:

where v and  are the equivalent single rotation axis and angle respectively, equal to:

are the equivalent single rotation axis and angle respectively, equal to:

An analytic derivation of these single rotation equivalent axis and angle is achieved by decomposing the total rotation to an infinite sequence of infinitesimally small rotations.[1]

The most common scenario, where simultaneous rotation around three orthogonal axes can be observed is when performing measurements with a gyroscope. The three simultaneous orthogonal rotations measured with a 3D gyroscope represent a single rotation around a certain axis for a certain angle. When the measured angular velocities or their proportions are constant, this rotation and the resulting angular orientation can be uniquely represented with SORA. When this condition is met, the orientation of the rotation axis does not change and the components of SORA are equal to the angles of three simultaneous rotations measured with a 3D gyroscope.

Using gyroscope measurements that provide rotation angle estimation, it is reasonable to combine angular velocities around three orthogonal axes in vector form:

Angular velocity vector  is orthogonal to the rotation plane, and its magnitude is equal to the angular velocity in that plane.

When the measured angular velocities or their proportions are approximately constant, the orientation of the rotation axis is also constant. It then holds:

is orthogonal to the rotation plane, and its magnitude is equal to the angular velocity in that plane.

When the measured angular velocities or their proportions are approximately constant, the orientation of the rotation axis is also constant. It then holds:

SORA represents a unique angular orientation of a rigid-body relative to some reference frame. Using SORA as a generalized representation of angular orientation, we can avoid the problem of rotation non-commutativity. As SORA indicates a single rotation for a specific angular orientation, the Gimbal problem is here avoided. Because of the mentioned, SORA is much more suitable for representation of angular orientation than widely used Euler angles.

SORA is simple and well-suited for use in the real-time calculation of orientation based on angular velocity measurements derived using a gyroscope, as long as the measured angular velocities or their proportions are approximately constant. Under this condition, using SORA, orientation calculation only requires a single step.[1] SORA is appropriate for use in a number of applications that require angular orientation information, including navigation and motion tracking.

Finally, SORA helps interpret the meaning of the rotation vector with measurable quantities.

Rotating a vector

Rodrigues' rotation formula (named after Olinde Rodrigues) is an efficient algorithm for rotating a Euclidean vector, given a rotation axis and an angle of rotation. In other words, the Rodrigues' formula provides an algorithm to compute the exponential map from so(3) to SO(3) without computing the full matrix exponent (the rotation matrix).

If v is a vector in  and ω is a unit vector describing an axis of rotation about which we want to rotate v by an angle θ (in a right-handed sense), the Rodrigues' formula to obtain the rotated vector is:

and ω is a unit vector describing an axis of rotation about which we want to rotate v by an angle θ (in a right-handed sense), the Rodrigues' formula to obtain the rotated vector is:

This is more efficient than converting ω and θ into a rotation matrix, and using the rotation matrix to compute the rotated vector.

Relationship to other representations

There are many ways to represent a rotation. It is useful to understand how different representations relate to one another, and how to convert between them.

Exponential map from so(3) to SO(3)

The exponential map is used as a transformation from axis-angle representation of rotations to rotation matrices.

Essentially, by using a Taylor expansion you can derive a closed form relationship between these two representations. Given a unit vector  representing the Euler axis, and an angle,

representing the Euler axis, and an angle,  , an equivalent rotation matrix is given by the following:

, an equivalent rotation matrix is given by the following:

where R is a 3×3 rotation matrix and ![[\omega ]_{\times }](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/9/2/3/0/923051764ceda963c9356fadbb12d809.png) is the cross product matrix of

is the cross product matrix of  . This can be easily derived from Rodrigues' rotation formula.

. This can be easily derived from Rodrigues' rotation formula.

Due to the existence of the above mentioned exponential map, the unit vector  representing the rotation axis, and the angle

representing the rotation axis, and the angle  are sometimes called the exponential coordinates of the rotation matrix R.

are sometimes called the exponential coordinates of the rotation matrix R.

Log map from SO(3) to so(3)

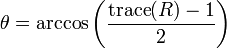

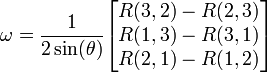

To retrieve the axis–angle representation of a rotation matrix calculate the angle of rotation:

and then use it to find the normalized axis:

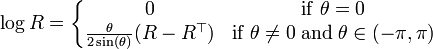

Note, also that the Matrix logarithm of the rotation matrix R is:

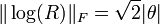

Except when R has eigenvalues equal to −1 where the log is not unique. However, even in the case where  the Frobenius norm of the log is:

the Frobenius norm of the log is:

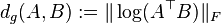

Note that given rotation matrices A and B:

is the geodesic distance on the 3D manifold of rotation matrices.

Note that for small rotations, the above computation of  may be numerically imprecise as the derivative of arccos goes to infinity as theta approaches zero. In that case, the off-axis terms will provide better information about

may be numerically imprecise as the derivative of arccos goes to infinity as theta approaches zero. In that case, the off-axis terms will provide better information about  , as for small angles,

, as for small angles, ![R\approx [{\mathbf {v}}]_{\times }+I](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/4/a/5/3/4a53b613ea000f4296aad8c0b3e8c750.png) where

where ![[{\mathbf {v}}]_{\times }](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/c/e/c/9/cec97c878eea1835df0d739c1d52b41b.png) is the matrix representation of the cross product.

is the matrix representation of the cross product.

This formulation also has numerical problems at  . There, the off-axis terms don't give information about the rotation axis (which is still defined up to a sign ambiguity). In that case, we must reconsider the above formula:

. There, the off-axis terms don't give information about the rotation axis (which is still defined up to a sign ambiguity). In that case, we must reconsider the above formula:

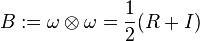

At  we have

we have

and so let

so the diagonal terms of B are the squares of the elements of  and the signs (up to sign ambiguity) can be determined from the signs of the off-axis terms of B.

and the signs (up to sign ambiguity) can be determined from the signs of the off-axis terms of B.

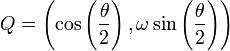

Unit quaternions

the following expression transforms axis–angle coordinates to versors (unit quaternions):

Given a versor,  , the axis-angle coordinates can be extracted using the following:

, the axis-angle coordinates can be extracted using the following:

A more numerically stable expression of the rotation angle is the following:

It may also be useful to know:

See also

- homogeneous coordinates

- screw theory, a representation of rigid body motions and velocities using the concepts of twists, screws and wrenches

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Stančin, Sara (2011). "Angle Estimation of Simultaneous Orthogonal Rotations from 3D Gyroscope Measurements". Sensors. doi:10.3390/s110908536.

![R=\exp([\omega ]_{\times }\theta )=\sum _{{k=0}}^{\infty }{\frac {([\omega ]_{\times }\theta )^{k}}{k!}}=I+[\omega ]_{\times }\theta +{\frac {1}{2!}}([\omega ]_{\times }\theta )^{2}+{\frac {1}{3!}}([\omega ]_{\times }\theta )^{3}+\cdots](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/1/8/f/9/18f92b03e94b26fc37c04731eeb45548.png)

![R=I+[\omega ]_{\times }\left(\theta -{\frac {\theta ^{3}}{3!}}+{\frac {\theta ^{5}}{5!}}-\cdots \right)+[\omega ]_{\times }^{2}\left({\frac {\theta ^{2}}{2!}}-{\frac {\theta ^{4}}{4!}}+{\frac {\theta ^{6}}{6!}}-\cdots \right)](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/b/9/6/5/b9655622b215e2f0c0beb05ff5d7d0a5.png)

![R=I+[\omega ]_{\times }\sin(\theta )+[\omega ]_{\times }^{2}(1-\cos(\theta ))](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/6/a/5/b/6a5b94e224a6659970b10cf2bb038164.png)

![R=I+2[\omega ]_{\times }^{2}=I+2(\omega \otimes \omega -I)=2\omega \otimes \omega -I](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/3/d/4/5/3d45b8ca93183d644527e8fab8ed708e.png)

![\theta =2\,\arctan 2(\|[x\,y\,z]\|,w)\,](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/b/6/7/d/b67dfe2bfbed7d9cf3860708dc4250e9.png)

![{\frac {q}{\sin(\theta /2)}}={\frac {[x\,y\,z]^{\top }}{\|[x\,y\,z]\|}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/7/e/6/2/7e62ec439b18a65cd8a79ac8a4556b3b.png)