Avignon

| Avignon | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| ||

Avignon | ||

|

Location within Provence-A.-C.d'A. region  Avignon | ||

| Coordinates: 43°57′N 4°49′E / 43.95°N 4.81°ECoordinates: 43°57′N 4°49′E / 43.95°N 4.81°E | ||

| Country | France | |

| Region | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur | |

| Department | Vaucluse | |

| Arrondissement | Avignon | |

| Intercommunality | Grand Avignon | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor (2008–2014) | Marie-Josée Roig (UMP) | |

| Area | ||

| • Land1 | 64.78 km2 (25.01 sq mi) | |

| Population (2006) | ||

| • Population2 | 94,787 | |

| • Population2 Density | 1,500/km2 (3,800/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET (GMT +1) | |

| INSEE/Postal code | 84007 / 84000 | |

| Elevation |

10–122 m (33–400 ft) (avg. 23 m or 75 ft) | |

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | ||

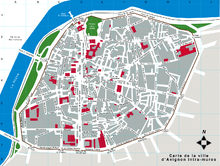

Avignon (French pronunciation: [a.viˈɲɔ̃]; Occitan: Avinhon in classical norm or Avignoun in Mistralian norm) is a French commune in southeastern France in the départment of the Vaucluse bordered by the left bank of the Rhône river. Of the 94,787 inhabitants of the city (as of 1 January 2010), about 12,000 live in the ancient town centre surrounded by its medieval ramparts.

Often referred to as the "City of Popes" because of the presence of popes and antipopes from 1309 to 1423 during the Catholic schism, it is currently the largest city and capital of the département of Vaucluse. This is one of the few French cities to have preserved its ramparts. In addition, its historic centre, the palace of the popes, Rocher des Doms, and the bridge of Avignon are well-preserved. It was classified a World Heritage Site by UNESCO under the criteria I, II and IV.

As a showcase of arts and culture, the fame of its annual theatre festival, known as the Festival d'Avignon, has far exceeded the French borders.

Geography

Avignon is situated on the left bank of the Rhône river, a few kilometres above its confluence with the Durance, about 580 km (360.4 mi) south-east of Paris, 229 km (142.3 mi) south of Lyon and 85 km (52.8 mi) north-north-west of Marseille. Its coordinates are 43°57′N 4°50′E / 43.950°N 4.833°E. Avignon occupies a large oval-shaped area, not fully populated and covered to a large extent by parks and gardens.

Climate

Avignon has a humid subtropical climate Cfa in the Köppen climate classification, with moderate rainfall year-round. The city is often subject to windy weather; the strongest wind is the mistral. The popular proverb is, however, somewhat exaggerated, Avenie ventosa, sine vento venenosa, cum vento fastidiosa (windy Avignon, pest-ridden when there is no wind, wind-pestered when there is)

| Climate data for Avignon | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 49 (9) |

53 (12) |

59 (15) |

67 (19) |

74 (23) |

82 (28) |

87 (31) |

87 (31) |

78 (26) |

68 (20) |

56 (13) |

50 (10) |

68 (20) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 34 (1) |

36 (2) |

41 (5) |

45 (7) |

51 (11) |

58 (14) |

61 (16) |

60 (16) |

57 (14) |

49 (9) |

41.2 (5.1) |

37.4 (3) |

48.2 (9) |

| Precipitation inches (mm) | 0.9 (23) |

1.3 (33) |

1.9 (48) |

2.1 (53) |

2.5 (64) |

1.7 (43) |

1.3 (33) |

1.8 (46) |

2.6 (66) |

3.3 (84) |

3 (80) |

2.1 (53) |

24.3 (617) |

| [citation needed] | |||||||||||||

Administration

Avignon is the préfecture (capital) of the Vaucluse département in the region of Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur. It forms the core of the Grand Avignon metropolitan area (communauté d'agglomération), which comprises twelve communes on both sides of the river:

- Les Angles, Rochefort-du-Gard, Saze and Villeneuve-lès-Avignon in the Gard département;

- Avignon, Caumont-sur-Durance, Jonquerettes, Morières-lès-Avignon, Le Pontet, Saint-Saturnin-lès-Avignon, Vedène and Velleron in the Vaucluse département.

History

| Historic Centre of Avignon: Papal Palace, Episcopal Ensemble and Avignon Bridge | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

| |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iv |

| Reference | 228 |

| UNESCO region | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

Early history

The site of Avignon was settled very early on; the rocky outcrop (le Rocher les Doms) at the north end of the town, overlooking the Rhône River, may have been the site of a Celtic oppidum or hill fort.

Avignon, written as Avennio or Avenio in the ancient texts and inscriptions, takes its name from the Avennius clan. Founded by the Gallic tribe of the Cavares or Cavari, it became the centre of an important Phocaean colony from Massilia (present Marseilles).

Under the Romans, Avenio was a flourishing city of Gallia Narbonensis, the first Transalpine province of the Roman Empire, but very little from this period remains (a few fragments of the forum near Rue Molière).

During the inroads of the Goths, it was badly damaged in the fifth century and belonged in turn to the Goths, the kingdoms of Burgundy and of Arles, in the 12th century.[1][2] It fell into the hands of the Saracens and was destroyed in 737 by the Franks under Charles Martel for having sided with the Arabs against him. Boso having been proclaimed Burgundian King of Provence, or of Arelat (after its capital Arles), by the Synod of Mantaille, at the death of Louis the Stammerer (879), Avignon ceased to belong to the Frankish kings.

In 1033, when Conrad II inherited the Kingdom of Arelat, Avignon passed to the Holy Roman Empire. With the German rulers at a distance, Avignon set up as a republic with a consular form of government, between 1135 and 1146. In addition to the Emperor, the Counts of Forcalquier, of Toulouse and of Provence exercised a purely nominal sway over the city; on two occasions, in 1125 and in 1251, the Counts of Toulouse and Provence divided their rights in regard to it, while the Count of Forcalquier resigned any right he possessed to the local Bishops and Consuls in 1135.

At the end of the twelfth century, Avignon declared itself an independent republic, but independence was crushed in 1226 during the crusade against the Albigenses (the dualist Cathar heresy centred in neighboring Albi). After the citizens refused to open the gates of Avignon to King Louis VIII of France and the papal Legate, a three-month siege ensued starting on 10 June 1226, and ending in capitulation by Avignon on 13 September 1226. Following the defeat, they were forced to pull down the ramparts and fill up the moat of the city.

On 7 May 1251 Avignon was made a common possession of counts Charles of Anjou and Alphonse de Poitiers, brothers of French king Saint Louis IX. On 25 August 1271, at the death of Alphonse de Poitiers, Avignon and the surrounding countship Comtat-Venaissin (which was governed by rectors from 1274 to 1791) were united with the French crown.

Avignon and the Comtat did not become French until 1791. In 1274, the Comtat became a possession of the popes, with Avignon itself, self-governing, under the overlordship of the Angevin count of Provence (who was also king of "Sicily" [i.e., Naples]). The popes were allowed by the count of Provence (a papal vassal) to settle in Avignon in the early 14th century. The popes bought Avignon from the Angevin ruler for 80,000 florins in 1348. From then on until the French Revolution, Avignon and the Comtat were papal possessions, first under the schismatic popes of the Great Schism, then under the popes of Rome ruling via legates and vice-legates. The Black Death appeared at Avignon in 1348; killing almost two-thirds of the city's population.[3]

Avignon and its popes

In 1309 the city, still part of the Kingdom of Arles, was chosen by Pope Clement V as his residence, and from 9 March 1309 until 13 January 1377 was the seat of the Papacy instead of Rome. This caused a schism in the Catholic Church. At the time, the city and the surrounding Comtat Venaissin were ruled by the kings of Sicily of the house of Anjou. The French King Philip the Fair, who had inherited from his father all the rights of Alphonse de Poitiers (the last Count of Toulouse), made them over to Charles II, King of Naples and Count of Provence (1290). Nonetheless, Philip was a shrewd ruler. Inasmuch as the eastern banks of the Rhone marked the edge of his kingdom, when the river flooded up into the city of Avignon, Philip taxed the city since during periods of flood, the city technically lay within his domain.

Papal Avignon

Regardless, on the strength of the donation of Avignon, Queen Joanna I of Sicily, as countess of Provence, sold the city to Clement VI for 80,000 florins on 9 June 1348 and, though it was later the seat of more than one antipope, Avignon belonged to the Papacy until 1791, when, during the disorder of the French Revolution, it was reincorporated with France.[4]

Seven popes resided there:

- Clement V: 1305–1314

- John XXII: 1316–1334

- Benedict XII: 1334–1342

- Clement VI: 1342–1352

- Innocent VI: 1352–1362

- Urban V: 1362–1370

- Gregory XI: 1370–1378

This period from 1309–1377 – the Avignon Papacy – was also called the Babylonian Captivity of exile, in reference to the Israelites' enslavement in biblical times.

The walls that were built by the popes in the years immediately following the acquisition of Avignon as papal territory are well preserved. As they were not particularly strong fortifications, the Popes relied instead on the immensely strong fortifications of their palace, the "Palais des Papes". This immense Gothic building, with walls 17–18 feet thick, was built 1335–1364 on a natural spur of rock, rendering it all but impregnable to attack. After its capture following the French Revolution, it was used as a barracks and prison for many years but it is now a museum.

Avignon, which at the beginning of the 14th century was a town of no great importance, underwent extensive development during the time the seven Avignon popes and two anti-popes, Clement V to Benedict XIII made their residences there. To the north and south of the rock of the Doms, partly on the site of the Bishop's Palace, which had been enlarged by John XXII, was built the Palace of the Popes, in the form of an imposing fortress consisting of towers, linked to each other, and named as follows: De la Campane, de Trouillas, de la Glacière, de Saint-Jean, des Saints-Anges (Benedict XII), de la Gâche, de la Garde-Robe (Clement VI), de Saint-Laurent (Innocent VI). The Palace of the Popes belongs, in virtue of its severe architecture, to the Gothic art of the South of France. Other noble examples can be seen in the churches of St. Didier, St. Peter and St. Agricola, as well as the Clock Tower, and in the fortifications built between 1349 and 1368 for a distance of some three miles (5 km), and flanked by thirty-nine towers, all of which were erected or restored by the Roman Catholic Church. The frescoes that are painted on the interiors of the Palace of the Popes and the churches of Avignon were created primarily by artists from Siena.

The popes were followed to Avignon by agents (factores) of the great Italian banking-houses, who settled in the city as money-changers, as intermediaries between the Apostolic Chamber and its debtors, living in the most prosperous quarters of the city, which was known as the Exchange. A crowd of traders of all kinds brought to market the produce necessary for maintaining the numerous court and for the visitors who flocked to it; grain and wine from Provence, from the south of France, the Roussillon and the country around Lyon. Fish was brought from places as distant as Brittany; cloths, rich stuffs and tapestries came from Bruges and Tournai. We need only glance at the account-books of the Apostolic Chamber, still kept in the Vatican archives, to get an idea of the trade of which Avignon became the centre. The university founded by Boniface VIII in 1303, had a good many students under the French popes, drawn there by the generosity of the sovereign pontiffs, who rewarded them with books or benefices.

During the Great Schism (1378–1415) the antipopes Clement VII and Benedict XIII returned to reside at Avignon. Clement VII lived in Avignon during his entire anti-pontificate, while Benedict XIII only lived there until 1403 when he was forced to flee to Aragon.

After the departure of the popes

After the restoration of the Papacy in Rome, the spiritual and temporal government of Avignon was entrusted to a gubernatorial Legate, notably the Cardinal-nephew, who was replaced, in his absence, by a vice-legate (contrary to the legate usually a commoner, and not a cardinal). But Pope Innocent XII abolished nepotism and the office of Legate in Avignon on 7 February 1693, handing over its temporal government in 1692 to the Congregation of Avignon (i.e. a department of the papal Curia, residing at Rome), with the Cardinal Secretary of State as presiding prefect, and exercising its jurisdiction through the vice-legate. This congregation, to which appeals were made from the decisions of the vice-legate, was united to the Congregation of Loreto within the Roman Curia; in 1774 the vice-legate was made president, thus depriving it of almost all authority. It was done away with under Pius VI on 12 June 1790.

The Public Council, composed of forty-eight councillors chosen by the people, four members of the clergy and four doctors of the university, met under the presidency of the chief magistrate of the city, the viquier (Occitan) or vicar or representative of the papal Legate or Vice-legate, who annually nominated a man for the post. The councillors' duty was to watch over the material and financial interests of the city; but their resolutions were to be submitted to the vice-legate for approval before being put in force. Three consuls, chosen annually by the Council, had charge of the administration of the streets.

Avignon's survival as a papal enclave was, however, somewhat precarious, as the French crown maintained a large standing garrison at Villeneuve-lès-Avignon just across the river.

From the fifteenth century onward it became the policy of the Kings of France to rule Avignon as part of their kingdom. In 1476, Louis XI, upset that Charles of Bourbon was made legate, sent troops to occupy the city, until his demands that Giuliano della Rovere be made legate, once Giuliano della Rovere was made a cardinal he withdrew his troops from the city.

In 1536 king Francis I of France invaded the papal territory, in order to overthrow Emperor Charles V, who was emperor of the territory. When he entered the city the people received him very well, and in return for the reception the people were all granted to them the same privileges that French subjects enjoyed, such as being able to hold state offices.

In (1583) King Henry III Valois attempted to offer an exchange of Marquisate of Saluzzo for Avignon, however his offer was refused by Pope Gregory XIII.

In 1663 in retaliation for the attack led by the Corsican Guard on the attendants of the Duc de Créqui, the ambassador of Louis XIV in Rome, he attacked and seized Avignon, which at the time was considered an important and integral part of the French Kingdom by the provincial Parliament of Provence.

In 1688 yet another attempt was made to occupy Avignon, however the attempt failed, and from 1688 to 1768 Avignon was at peace with no occupations or wars during that time.

King Louis XV occupied the Comtat Venaissin from 1768 to 1774 and substituted French institutions for those in force with the approval of the people of Avignon; a French party grew up.

In 1791 that French party, after the sanguinary massacres of La Glacière between the adherents of the Papacy and the Republicans (16–17 October 1791), carried all before it, and induced the Constituent Assembly to decree the union of Avignon and the Comtat (comital district) Venaissin with France on 14 September 1791. On 25 June 1793 Avignon and Comtat-Venaissin were integrated along with the former principality of Orange to form the present republican département Vaucluse.

Article 5 of the Treaty of Tolentino (19 February 1797) definitively sanctioned the annexation, stating that "The Pope renounces, purely and simply, all the rights to which he might lay claim over the city and territory of Avignon, and the Comtat Venaissin and its dependencies, and transfers and makes over the said rights to the French Republic." In 1801 the territory had 191,000 inhabitants.

On 30 May 1814, the French annexation was recognized by the Pope. Ercole Consalvi made an ineffectual protest at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 but Avignon was never restored to the Holy See. In 1815 Bonapartist Marshal Guillaume Marie Anne Brune was assassinated in the town by adherents of the royalist party during the White Terror.

Ecclesiastical history of the (Arch)diocese

It was the seat of a bishop as early as the year 70 AD. The first bishop known to history is Nectarius, who took part in several councils about the middle of the fifth century. St. Magnus was a Gallo-Roman senator who became a monk and then bishop of the city. His son, St. Agricol (Agricolus), bishop between 650 and 700, is the patron saint of Avignon. Several synods of minor importance were held there, and its university, founded by Pope Boniface VIII in 1303 and famed as a seat of legal studies, flourished until the French Revolution. The memory of St. Eucherius still clings to three vast caves near the village of Beaumont, whither, it is said, the people of Lyon had to go in search of him when they sought him to make him their archbishop. As Bishop of Cavaillon, Cardinal Philippe de Cabassoles, seigneur of Vaucluse, was the great protector of the Renaissance poet Petrarch.

In 1309 the city was chosen by Clement V as his residence, and from that time till 1377 was the papal seat. In 1348 the city was sold by Joanna, Countess of Provence, to Clement VI for 80,000 florins.

In 1475 pope Sixtus IV raised the diocese of Avignon to the rank of an archbishopric, in favour of his nephew Giuliano della Rovere, who later became Pope Julius II. The Archdiocese of Avignon has canonic jurisdiction over the department of Vaucluse. Before the French Revolution it had as suffragan sees Carpentras, Vaison and Cavaillon, which were united by the Napoleonic Concordat of 1801 to Avignon, together with the Diocese of Apt, a suffragan of Aix-en-Provence. However, at that same time Avignon was reduced to the rank of a bishopric and was made a suffragan see of Aix. The Archdiocese of Avignon was re-established in 1822, receiving as suffragan sees the Diocese of Viviers (restored in 1822), Valence: (formerly under Lyon), Nîmes (restored in 1822) and Montpellier (formerly under Toulouse).

In 2002, as part of the reshuffling of the ecclesiastic provinces of France, the Archdiocese of Avignon ceased to be a metropolitan and became, instead a suffragan diocese of the new province of Marseilles, while keeping its rank of archdiocese.

Councils of Avignon

The Councils of Avignon are Councils of the Roman Catholic Church. The first reported council was held in 1060, though nothing is known about the events of the council. In 1080 another council was held, with Hugues de Dié, papal legate as council president. During the 1080 council Aicard, usurper of the See of Arles was deposed, and Gibelin placed in his position. Three bishops-elect (Lautelin of Embrun, Hugues of Grenoble, Didier of Cavaillon) accompanied the legate to Rome and were consecrated there by Pope Gregory VII.

During the 13th century four councils were held, including the 1209 council in which the inhabitants of Toulouse were excommunicated from the church by the council for failing to expel the Albigensian heretics from Toulouse. Included in the population that was excommunicated were two papal legates, four archbishops and twenty bishops. The next council was held in 1270, and Bertrand de Malferrat, Archbishop of Arles presided over the council. The usurpers of ecclesiastical property were severely threatened; unclaimed legacies were allotted to pious uses; the bishops were urged to mutually support one another; and individual churches were taxed for the support of the papal legates; and ecclesiastics were forbidden to convoke the civil courts against their bishops. And the council banned Christmas carols.

During the 1279 council they were concerned with the clergy's protection of rights, privileges, and immunities. Provisions were also made for those who promised to join the crusade Gregory X had ordered, but had failed to actually go on the crusade. In addition the council decreed that to hear confessions monks must have permission of their ordinary, or bishop, as well as their superior. The last council during the 13th century was the council of 1282, during which they published 10 canons. Among the canons published was one urging people to more regularly attend the parochial churches, and to go to their parish church for at least feast days and on Sundays.

During the 1327 council the temporalities of the Church and ecclesiastical jurisdiction occupied their attention. The council published seventy-nine canons in 1337. The 79 canons were renewed from earlier councils, and emphasized the duty of Easter Communion in one's own parish church, and of abstinence on Saturday for beneficed persons and ecclesiastics, in honour of the Blessed Virgin, a practice begun three centuries earlier on the occasion of the Truce of God, but no longer universal.

The 15th century saw two councils convened, one in 1457 and one in 1497. The 1457 council was held by Cardinal de Foix, Archbishop of Arles and legate of Avignon, who was also a Franciscan. His primary reason was to promote the doctrine of Immaculate Conception, in sense of the declaration of the council of Basle. They forbade the preaching of the contrary doctrine, as well as 64 disciplinary canons that were published, in keeping with the legislation of previous councils. In 1497 Archbishop Francesco Tarpugi (after the council he was cardinal) presided over the council. They published a similar number of decrees to the 1457 council. It was decreed that the sponsors of the newly confirmed were not obligated to make presents to their parents or to them. They also decreed that before the relics of the saints two candles were to be kept lit at all times.

During the next five centuries only six further councils were held. The 1509 council focused on disciplinary measures. The next council, in 1596, was called to discuss the furthering of the observance of the decrees of the Council of Trent., and the 1609 council was held for very similar circumstances. The councils of 1664 and 1725 were held to formulate disciplinary decrees. The 1725 council also decreed the duty of adhering to the Papal Bull Unigenitus (1713) of Clement XI that condemned the Oratorian, Pasquier Quesnel. The final council on record was in 1849 and it published ten chapters of canons concerning discipline and faith.

University of Avignon

The University of Avignon (1303–1792),[5] formed from the existing schools of the city, and was formally constituted in 1303, by Boniface VIII in a Papal Bull. Boniface VIII, and King Charles II of Naples should be considered one of the first great protectors and benefactors to the University of Avignon. The Law department within the university has always been its most important department, covering both civil and ecclesiastical law. The law department existed nearly exclusively for some time after the university's formation and remained the most important department through its existence.

In 1413 Antipope John XXIII founded the University's department of Theology, which for quite some time had only a few students. The university's art department never did gain any great importance. It was not until the 16th and 17th centuries that the school developed a department of medicine. The Bishop of Avignon was chancellor of the university from 1303 to 1475, after 1475 the bishop became and Archbishop, but remained chancellor of the university.The papal vice-legate, generally a bishop, represented the civil power (in this case the pope) and was chiefly a judicial officer, ranking higher than the Primicerius (Rector).

The Primicerius was elected by the Doctors of Law. In 1503 the Doctors of Law had 4 Theologians, and in 1784 two Doctors of Medicine added their ranks. Since the Pope was the spiritual head, and after 1348, the temporal ruler of Avignon, he was able to have a great deal of influence in all university affairs. In 1413, John XXIII granted the university extensive special privileges, such as university jurisdiction, and tax exempt status. Circumstances in the latter part of the university's existence such as political, geographical, and educational, caused the university to seek favour from Paris rather than Rome for protection and favour. During the chaos of the French Revolution the university started to gradually disappear, and in 1792 the university was abandoned and closed. Currently the university has been superseded by the modern Université of Avignon and Vaucluse.[6]

Main sights

In the part of the city within the walls, the buildings are old but in most areas they have been restored or reconstructed (such as the post office and the Lycée Frédéric Mistral).[7] The buildings along the main street, Rue de la République, date from the Second Empire (1852–70) with Haussmann façades and amenities around Place de l'Horloge (the central square), the neoclassical city hall, and the theater district. In 1960, Avignon was the subject of considerable debate during the creation of conservation areas. The then mayor of the district proposing a renovation of the district known as the Quartier de la Balance, that incurred the demolition of about two-thirds of the area, keeping only the listed buildings. The solution was adopted as a compromise, with a part of the neighborhood near the Palace Square actually enjoying a true restoration[8]

- Notre Dame des Doms, the cathedral, is a Romanesque building, mainly built during the 12th century, the most prominent feature of the cathedral is the gilded statue of the Virgin which surmounts the western tower. The mausoleum of Pope John XXII is one of the most beautiful works within the cathederal, it is a noteworthy example of 14th-century Gothic carving.

- Palais des Papes ("Papal Palace"), almost dwarfs the cathedral. The palace is an impressive monument and sits within a square of the same name. The palace was begun in 1316 by John XXII and continued by succeeding popes through the 14th century, until 1370 when it was finished.

- Minor churches of the town include, among the others, St Pierre, which has a graceful façade and richly carved doors, St Didier and St Agricol, all three of which were built in the Gothic architectural style.

- Civic buildings are represented most notably by the Hôtel de Ville (city hall), a modern building with a belfry of the 14th century, and the old Hôtel des Monnaies, the papal mint which was built in 1610 and became a music-school.

- Ramparts, built by the popes in the 14th century, still encircle Avignon and they are one of the finest examples of medieval fortification in existence. The walls of great strength are surmounted by machicolated sattlements, flanked at intervals by thirty-nine massive towers and pierced by several gateways, three of which date from the fourteenth century. The walls were restored under the direction of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

- Bridges include the little bridge which leads over the river to Villeneuve-les-Avignon, and a little higher up, a picturesque ruined bridge of the 12th century, the Pont Saint-Bénézet, projects into the river.

- Pont d'Avignon (Pont St-Bénézet, see below) Only four of the eighteen piles are left; on one of them stands the small Romanesque chapel of Saint-Bénézet. But the bridge is best known for the famous French song Sur le pont d'Avignon.

- The Calvet Museum, so named after Esprit Calvet, a physician who in 1810 left his collections to the town, has a strong collection of paintings, metalwork and other collections. The library has over 140,000 volumes.

- The town has a statue of Jean Althen, who migrated from Persia and in 1765 introduced the culture of the madder plant, which long formed the staple — and is still an important tool — of the local cloth trade in the area.

- The Musée du Petit Palais (opened 1976) at the end of the square overlooked by the Palais des Papes, has an exceptional collection of Renaissance paintings of the Avignon school as well as from Italy, which reunites many "primitives" from the collection of Giampietro Campana.

- Collection Lambert, housing contemporary art exhibitions

- Musée Angladon, which exhibits the paintings of a private collector who created the museum

- Musée Lapidaire, with the archeological and medieval sculpture collections of the Fondation Calvet, in the old chapel of the Jesuit College.

- Musée Louis-Vouland

- Musée Requien

- Palais du Roure

- Les Halles is a large indoor market that offers fresh produce, meats, and fish along with a variety of other goods.

- Place Pie is a small square near Place de l'Horloge where you can partake in an afternoon coffee on the outdoor terraces or enjoy a night on the town later in the evening as the square fills with young people.

Culture

Avignon Festival

A famous theatre festival is held annually in Avignon. Founded in 1947, the Avignon Festival comprises traditional theatrical events as well as other art forms such as dance, music, and cinema, making good use of the town's historical monuments. Every summer approximately 100,000 people attend the festival.[9] There are really two festivals that take place: the more formal "Festival In", which presents plays inside the Palace of the Popes and the more bohemian "Festival Off", which is known for its presentation of largely undiscovered plays and street performances.

The International Congress Centre

It was created in 1976 within the outstanding premises of the Palace of the Popes and hosts many events throughout the entire year. The Congress Centre, designed for conventions, seminars, and meetings for 10 to 550 persons, now occupies two wings of the Popes' Palace.[10]

Sport

Sporting Olympique Avignon is the local rugby league football team. During the 20th century it produced a number of French international representative players.

AC Arles-Avignon is a professional French football team. They compete in Ligue 2, having gained promotion from Ligue 3 in the 2009-2010 season. They play at the Parc des Sports, which has a capacity of just over 17,000.

Transport

Avignon has an SNCF railway station, Gare d'Avignon-Centre, situated just outside the ramparts of the old town, and the Gare d'Avignon TGV outside the town, served by the LGV Méditerranée, a high-speed rail system.[11] Provision for transport within the city includes 23 bus lines, and 110 kilometres (68 miles) of bike paths with a bike-sharing program vélopop'.[11][12] Two tram lines are projected to open in 2016, with works expected to begin in the late 2013.[13]

The Avignon - Caumont Airport is situated about 8 kilometres (5 miles) southeast of Avignon.

Avignon is situated on the banks of the river Rhone, one of the main water thoroughfares in France.

Nuclear pollution

On 8 July 2008 waste containing unenriched uranium leaked into two rivers from a nuclear plant in southern France. Some 30,000 L (7,925 gallons) of solution containing 12 g of uranium per litre spilled from an overflowing reservoir at the facility – which handles liquids contaminated by uranium – into the ground and into the Gaffiere and Lauzon rivers. The authorities kept this a secret from public for 12 hours, then issued a statement prohibiting swimming and fishing in the Gaffiere and Lauzon rivers.[14]

Sur le Pont d'Avignon

Avignon is commemorated by the French children's song, "Sur le Pont d'Avignon" ("On the bridge of Avignon"), which describes folk dancing. The bridge of the song is the Saint Bénézet bridge, over the Rhône River, of which only four arches (out of the initial 22) remain which start from the Avignon side of the river. In fact people would have danced beneath the bridge (sous le pont) where it crossed an island (Île de Barthelasse) on its way to Villeneuve-lès-Avignon. The bridge was initially built between 1171 and 1185, with an original length of some 900 m (2950 ft), but it suffered frequent collapses during floods and had to be rebuilt several times. Several arches were already missing (and spanned by wooden sections) before the remainder were destroyed in 1660.

People who were born or died in Avignon

- Trophime Bigot, French painter, died in Avignon in around 1653

- Jean Alesi, racing car driver - born in Avignon, 1964

- Henri Bosco, writer - born in Avignon, 1888

- Pierre Boulle, author of The Bridge over the River Kwai and Planet of the Apes - born in Avignon, 1912

- Alexandre de Rhodes (1591–1664), Jesuit missionary - born in Avignon

- Bernard Kouchner, politician - born in Avignon, 1936

- Mireille Mathieu, singer - born in Avignon, 1946

- Olivier Messiaen, composer - born in Avignon, 1908

- Joseph Vernet, painter - born in Avignon, 1714

- John Stuart Mill died at Avignon in 1873, and is buried in the cemetery.

- Dorothea von Rodde-Schlözer, artist and scholar died in Avignon in 1825.

- Michel Trinquier, painter born in 1930 in Avignon,

- René Girard, historian, literary critic, philosopher, and author - born in Avignon, 1923

- Cédric Carrasso, footballer - born in Avignon, 1981

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Avignon is twinned with:[15][16]

|

See also

- Avignon Foot 84

- Battle of Avignon (737)

- Montfavet

- Siena Italy

Notes

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/85188/Burgundy/253115/History#ref=ref115889

- ↑ William R. Shepherd, Historical Atlas 56, 58, 61, 66, 69, 72, 76 In 736

- ↑ "Epidemiology of the Black Death and Successive Waves of Plague". Medical History. Samuel K Cohn Jr, Department of History, University of Glasgow.

- ↑ Stephens, Henry Morse (1893). Revolutionary Europe, 1789–1815. London, England: Rivingtons. pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia (1913).

- ↑ "Website of University of Avignon". Univ-avignon.fr. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ↑ / AE / panneaux.donut? cid = 18 The Planning XXe

- ↑ Report Available: Where Avignon is detailed pages 180 to 183.

- ↑ "Festival 2014". Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ "Popes' Palace". Palais-des-papes.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Official guide to transport in Avignon". Avignon.fr. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ↑ http://velopop.fr

- ↑ "Le tramway : Un projet optimisé pour 2016 | Communauté d'Agglomération du Grand Avignon". Grandavignon.fr. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "Europe , Warning over French uranium leak". BBC News. 9 July 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 15.9 "Jumelages et Relations Internationales - Avignon". Avignon.fr (in French). Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 16.8 16.9 "Atlas français de la coopération décentralisée et des autres actions extérieures". Ministère des affaires étrangères (in French). Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- ↑ Francis, Valerie. "Twin Town News - Colchester, Avignon, Imola and Wetzlar". The Colchester Twinning Society. Retrieved 2013-07-22.

- ↑ "British towns twinned with French towns [via WaybackMachine.com]". Archant Community Media Ltd. Retrieved 2013-07-12.

References

"Avignon". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Avignon". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. "Councils of Avignon". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Councils of Avignon". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. "University of Avignon". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"University of Avignon". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Avignon". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Avignon". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

- d'Arbois de Jubainville, Recherches sur l'origine de la propriété foncière et des noms des lieux habités en France (Paris, 1890), 518

- Fantoni Castrucci, Istoria della città d'Avignone e del Contado Venesino (Venice, 1678)

- J. B. Joudou, Histoire des souverains pontifes qui ont siégé à Avignon (Avignon, 1855)

- A. Canron, Guide de l'étranger dans la ville d'Avignon et ses environs (Avignon, 1858)

- J. F. André, Histoire de la Papauté à Avignon (Avignon, 1887).

- "Avignon", A Handbook for Travellers in France (8th ed.), London: J. Murray, 1861

- Thomas Okey (1911), The Story of Avignon, London: J.M. Dent & Sons, OCLC 1135525

- "Avignon", Southern France, including Corsica (6th ed.), Leipzig: Baedeker, 1914

- Catholic hierarchy – includes recent diocesan statistics

- WorldStatesmen- France; includes lists of papal (Vice-)Legates

- Martin Garrett, Provence: a Cultural History (Oxford, 2006)

External links

Media related to Avignon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Avignon at Wikimedia Commons- Tourist office website

- City council website

- Avignon theater festival website

- Avignon/New York & Avignon film festivals website

- Comprehensive Insider's Guide to Avignon in English

Avignon travel guide from Wikivoyage

Avignon travel guide from Wikivoyage- Information and photos from ProvenceBeyond website

- BBC News: Warning over French uranium leak

- Live Camera Avignon, France

| |||||||||||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||||

.svg.png)