Arbelos

In geometry, an arbelos is a plane region bounded by a semicircle of diameter 1, connected at the corners to semicircles of diameters r and (1 − r), all rising above a common baseline. Archimedes is believed to be the first mathematician to study its mathematical properties, as it appears in propositions four through eight of his Book of Lemmas. Arbelos literally means "shoemaker's knife" in Greek; it resembles the blade of a knife used by cobblers from antiquity to the current day.[1]

Properties

Area

A circle with a diameter HA is equal in area with the arbelos

Proof

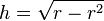

If BC = 1 and BA = r, then

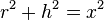

- In triangle BHA:

- In triangle CHA:

- In triangle BHC:

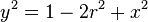

By substitution:  . By expansion:

. By expansion:  . By substituting for y2 into the equation for triangle BHC and solving for x:

. By substituting for y2 into the equation for triangle BHC and solving for x:

By substituting this, solve for y and h

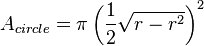

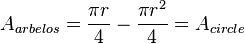

The radius of the circle with center O is:

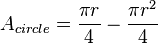

Therefore, the area is:

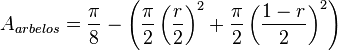

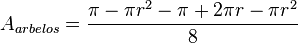

The area of the arbelos is the area of the large semicircle minus the area of the two smaller semicircles. Therefore the area of the arbelos is:

Q.E.D.[2]

This property appears as Proposition 4 in Archimedes' Book of Lemmas:

If AB be the diameter of a semicircle and N any point on AB, and if semicircles be described within the first semicircle and having AN, BN as diameters respectively, the figure included between the circumferences of the three semicircles is [what Archimedes called "αρβελος"]; and its area is equal to the circle on PN as diameter, where PN is perpendicular to AB and meets the original semicircle in P.

Rectangle

The segment BH intersects the semicircle BA at D. The segment CH intersects the semicircle AC at E. Then DHEA is a rectangle.

- Proof: Angles BDA, BHC, and AEC are right angles because they are inscribed in semicircles (by Thales' theorem). The quadrilateral ADHE therefore has three right angles, so it is a rectangle. Q.E.D.

Tangents

The line DE is tangent to semicircle BA at D and semicircle AC at E.

- Proof: Since angle BDA is a right angle, angle DBA equals π/2 minus angle DAB. However, angle DAH also equals π/2 minus angle DAB (since angle HAB is a right angle). Therefore triangles DBA and DAH are similar. Therefore angle DIA equals angle DOH, where I is the midpoint of BA and O is the midpoint of AH. But AOH is a straight line, so angle DOH and DOA are supplementary angles. Therefore the sum of angles DIA and DOA is π. Angle IAO is a right angle. The sum of the angles in any quadrilateral is 2π, so in quadrilateral IDOA, angle IDO must be a right angle. But ADHE is a rectangle, so the midpoint O of AH (the rectangle's diagonal) is also the midpoint of DE (the rectangle's other diagonal). As I (defined as the midpoint of BA) is the center of semicircle BA, and angle IDE is a right angle, then DE is tangent to semicircle BA at D. By analogous reasoning DE is tangent to semicircle AC at E. Q.E.D.

See also

- Archimedes' circles

- Archimedes' quadruplets

- Bankoff circle

- Ideal triangle

- Schoch circles

- Schoch line

- Woo circles

- Pappus chain

- Salinon

References

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Arbelos", MathWorld.

- ↑ Behnaz Rouhani. "The Arbelos". Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- ↑ "Arbelos - the Shoemaker's Knife". Cut the Knot. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

Bibliography

- Johnson RA (1960). Advanced Euclidean Geometry: An elementary treatise on the geometry of the triangle and the circle (reprint of 1929 edition by Houghton Miflin ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-486-46237-0.

- Ogilvy CS (1990). Excursions in Geometry. Dover. pp. 51–54. ISBN 0-486-26530-7

- Sondow J (2012). "The parbelos, a parabolic analog of the arbelos". arXiv:1210.2279 [math.HO]. American Mathematical Monthly, 120 (2013), 929-935.

- Wells D (1991). The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 5–6. ISBN 0-14-011813-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arbelos. |

- Arbelos – Amazing Properties (an interactive applet illustrating many Arbelos properties) at www.retas.de

- Arbelos at cut-the-knot

- Arbelos and Parbelos at PlanetMath