Animal

| Animals Temporal range: Ediacaran – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| (Unranked) | Opisthokonta |

| (Unranked) | Holozoa |

| (Unranked) | Filozoa |

| Kingdom: | Animalia Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Phyla | |

| |

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms of the kingdom Animalia or Metazoa. Their body plan eventually becomes fixed as they develop, although some undergo a process of metamorphosis later on in their lives. Most animals are motile, meaning they can move spontaneously and independently. All animals must ingest other organisms or their products for sustenance (see Heterotroph).

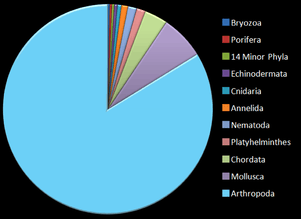

Most known animal phyla appeared in the fossil record as marine species during the Cambrian explosion, about 542 million years ago. Animals are divided into various sub-groups, some of which are: vertebrates (birds, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, fish); mollusks (clams, oysters, octopuses, squid, snails); arthropods (millipedes, centipedes, insects, spiders, scorpions, crabs, lobsters, shrimp); annelids (earthworms, leeches); sponges; and jellyfish.

Etymology

The word "animal" comes from the Latin word animalis, meaning "having breath".[2] In everyday colloquial usage the word incorrectly excludes humans—that is, "animal" is often used to refer only to non-human members of the kingdom Animalia. Sometimes, only closer relatives of humans such as mammals and other vertebrates are meant in colloquial use.[3] The biological definition of the word refers to all members of the kingdom Animalia, encompassing creatures as diverse as sponges, jellyfish, insects, and humans.[4]

Characteristics

Animals have several characteristics that set them apart from other living things. Animals are eukaryotic and multicellular,[5] which separates them from bacteria and most protists. They are heterotrophic,[6] generally digesting food in an internal chamber, which separates them from plants and algae.[7] They are also distinguished from plants, algae, and fungi by lacking rigid cell walls.[8] All animals are motile,[9] if only at certain life stages. In most animals, embryos pass through a blastula stage,[10] which is a characteristic exclusive to animals.

Structure

With a few exceptions, most notably the sponges (Phylum Porifera) and Placozoa, animals have bodies differentiated into separate tissues. These include muscles, which are able to contract and control locomotion, and nerve tissues, which send and process signals. Typically, there is also an internal digestive chamber, with one or two openings.[11] Animals with this sort of organization are called metazoans, or eumetazoans when the former is used for animals in general.[12]

All animals have eukaryotic cells, surrounded by a characteristic extracellular matrix composed of collagen and elastic glycoproteins.[13] This may be calcified to form structures like shells, bones, and spicules.[14] During development, it forms a relatively flexible framework[15] upon which cells can move about and be reorganized, making complex structures possible. In contrast, other multicellular organisms, like plants and fungi, have cells held in place by cell walls, and so develop by progressive growth.[11] Also, unique to animal cells are the following intercellular junctions: tight junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes.[16]

Reproduction and development

Nearly all animals undergo some form of sexual reproduction.[17] They have a few specialized reproductive cells, which undergo meiosis to produce smaller, motile spermatozoa or larger, non-motile ova.[18] These fuse to form zygotes, which develop into new individuals.[19]

Many animals are also capable of asexual reproduction.[20] This may take place through parthenogenesis, where fertile eggs are produced without mating, budding, or fragmentation.[21]

A zygote initially develops into a hollow sphere, called a blastula,[22] which undergoes rearrangement and differentiation. In sponges, blastula larvae swim to a new location and develop into a new sponge.[23] In most other groups, the blastula undergoes more complicated rearrangement.[24] It first invaginates to form a gastrula with a digestive chamber, and two separate germ layers — an external ectoderm and an internal endoderm.[25] In most cases, a mesoderm also develops between them.[26] These germ layers then differentiate to form tissues and organs.[27]

Food and energy sourcing

All animals are heterotrophs, meaning that they feed directly or indirectly on other living things.[28] They are often further subdivided into groups such as carnivores, herbivores, omnivores, and parasites.[29]

Predation is a biological interaction where a predator (a heterotroph that is hunting) feeds on its prey (the organism that is attacked).[30] Predators may or may not kill their prey prior to feeding on them, but the act of predation always results in the death of the prey.[31] The other main category of consumption is detritivory, the consumption of dead organic matter.[32] It can at times be difficult to separate the two feeding behaviours, for example, where parasitic species prey on a host organism and then lay their eggs on it for their offspring to feed on its decaying corpse. Selective pressures imposed on one another has led to an evolutionary arms race between prey and predator, resulting in various antipredator adaptations.[33]

Most animals indirectly use the energy of sunlight by eating plants or plant-eating animals. Most plants use light to convert inorganic molecules in their environment into carbohydrates, fats, proteins and other biomolecules, characteristically containing reduced carbon in the form of carbon-hydrogen bonds. Starting with carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O), photosynthesis converts the energy of sunlight into chemical energy in the form of simple sugars (e.g., glucose), with the release of molecular oxygen. These sugars are then used as the building blocks for plant growth, including the production of other biomolecules.[11] When an animal eats plants (or eats other animals which have eaten plants), the reduced carbon compounds in the food become a source of energy and building materials for the animal.[34] They are either used directly to help the animal grow, or broken down, releasing stored solar energy, and giving the animal the energy required for motion.[35][36]

Animals living close to hydrothermal vents and cold seeps on the ocean floor are not dependent on the energy of sunlight.[37] Instead chemosynthetic archaea and bacteria form the base of the food chain.[38]

Origin and fossil record

Animals are generally considered to have evolved from a flagellated eukaryote.[39] Their closest known living relatives are the choanoflagellates, collared flagellates that have a morphology similar to the choanocytes of certain sponges.[40] Molecular studies place animals in a supergroup called the opisthokonts, which also include the choanoflagellates, fungi and a few small parasitic protists.[41] The name comes from the posterior location of the flagellum in motile cells, such as most animal spermatozoa, whereas other eukaryotes tend to have anterior flagella.[42]

The first fossils that might represent animals appear in the Trezona Formation at Trezona Bore, West Central Flinders, South Australia.[43] These fossils are interpreted as being early sponges. They were found in 665-million-year-old rock.[43]

The next oldest possible animal fossils are found towards the end of the Precambrian, around 610 million years ago, and are known as the Ediacaran or Vendian biota.[44] These are difficult to relate to later fossils, however. Some may represent precursors of modern phyla, but they may be separate groups, and it is possible they are not really animals at all.[45]

Aside from them, most known animal phyla make a more or less simultaneous appearance during the Cambrian period, about 542 million years ago.[46] It is still disputed whether this event, called the Cambrian explosion, is due to a rapid divergence between different groups or due to a change in conditions that made fossilization possible.

Some paleontologists suggest that animals appeared much earlier than the Cambrian explosion, possibly as early as 1 billion years ago.[47] Trace fossils such as tracks and burrows found in the Tonian era indicate the presence of triploblastic worms, like metazoans, roughly as large (about 5 mm wide) and complex as earthworms.[48] During the beginning of the Tonian period around 1 billion years ago, there was a decrease in Stromatolite diversity, which may indicate the appearance of grazing animals, since stromatolite diversity increased when grazing animals went extinct at the End Permian and End Ordovician extinction events, and decreased shortly after the grazer populations recovered. However the discovery that tracks very similar to these early trace fossils are produced today by the giant single-celled protist Gromia sphaerica casts doubt on their interpretation as evidence of early animal evolution.[49][50]

Groups of animals

Ctenophora, Porifera, Placozoa, Cnidaria and Bilateria

Phylogenetic analysis suggests that the Porifera and Ctenophora diverged before a clade (ParaHoxozoa) that gave rise to the Bilateria, Cnidaria and Placozoa.[51] Another study based on the presence/absence of introns suggests that Cnidaria, Porifera and Placozoa may be a sister group of Bilateria and Ctenophora.[52] A new study indicates that Ctenophora are the basal first diverging clade of animals, with Porifera, and Placozoa and finally Bilateria and Cnidaria subsequent derivatives.[53]

The sponges (Porifera) were long thought to have diverged from other animals early.[54] They lack the complex organization found in most other phyla.[55] Their cells are differentiated, but in most cases not organized into distinct tissues.[56] Sponges typically feed by drawing in water through pores.[57] Archaeocyatha, which have fused skeletons, may represent sponges or a separate phylum.[58] However, a phylogenomic study in 2008 of 150 genes in 29 animals across 21 phyla revealed that it is the Ctenophora or comb jellies which are the basal lineage of animals, at least among those 21 phyla. The authors speculate that sponges—or at least those lines of sponges they investigated—are not so primitive, but may instead be secondarily simplified.[59]

Among the other phyla, the Ctenophora and the Cnidaria, which includes sea anemones, corals, and jellyfish, are radially symmetric and have digestive chambers with a single opening, which serves as both the mouth and the anus.[60] Both have distinct tissues, but they are not organized into organs.[61] There are only two main germ layers, the ectoderm and endoderm, with only scattered cells between them. As such, these animals are sometimes called diploblastic.[62] The tiny placozoans are similar, but they do not have a permanent digestive chamber.

The remaining animals form a monophyletic group called the Bilateria. For the most part, they are bilaterally symmetric, and often have a specialized head with feeding and sensory organs. The body is triploblastic, i.e. all three germ layers are well-developed, and tissues form distinct organs. The digestive chamber has two openings, a mouth and an anus, and there is also an internal body cavity called a coelom or pseudocoelom. There are exceptions to each of these characteristics, however — for instance adult echinoderms are radially symmetric, and certain parasitic worms have extremely simplified body structures.

Genetic studies have considerably changed our understanding of the relationships within the Bilateria. Most appear to belong to two major lineages: the deuterostomes and the protostomes, the latter of which includes the Ecdysozoa, Platyzoa, and Lophotrochozoa. In addition, there are a few small groups of bilaterians with relatively similar structure that appear to have diverged before these major groups. These include the Acoelomorpha, Rhombozoa, and Orthonectida. The Myxozoa, single-celled parasites that were originally considered Protozoa, are now believed to have developed from the Medusozoa as well.

Deuterostomes

Deuterostomes differ from the other Bilateria, called protostomes, in several ways. In both cases there is a complete digestive tract. However, in protostomes, the first opening of the gut to appear in embryological development (the archenteron) develops into the mouth, with the anus forming secondarily. In deuterostomes the anus forms first, with the mouth developing secondarily.[63] In most protostomes, cells simply fill in the interior of the gastrula to form the mesoderm, called schizocoelous development, but in deuterostomes, it forms through invagination of the endoderm, called enterocoelic pouching.[64] Deuterostome embryos undergo radial cleavage during cell division, while protostomes undergo spiral cleavage.[65]

All this suggests the deuterostomes and protostomes are separate, monophyletic lineages. The main phyla of deuterostomes are the Echinodermata and Chordata.[66] The former are radially symmetric and exclusively marine, such as starfish, sea urchins, and sea cucumbers.[67] The latter are dominated by the vertebrates, animals with backbones.[68] These include fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.[69]

In addition to these, the deuterostomes also include the Hemichordata, or acorn worms.[70] Although they are not especially prominent today, the important fossil graptolites may belong to this group.[71]

The Chaetognatha or arrow worms may also be deuterostomes, but more recent studies suggest protostome affinities.

Ecdysozoa

.jpg)

The Ecdysozoa are protostomes, named after the common trait of growth by moulting or ecdysis.[72] The largest animal phylum belongs here, the Arthropoda, including insects, spiders, crabs, and their kin. All these organisms have a body divided into repeating segments, typically with paired appendages. Two smaller phyla, the Onychophora and Tardigrada, are close relatives of the arthropods and share these traits.

The ecdysozoans also include the Nematoda or roundworms, perhaps the second largest animal phylum. Roundworms are typically microscopic, and occur in nearly every environment where there is water.[73] A number are important parasites.[74] Smaller phyla related to them are the Nematomorpha or horsehair worms, and the Kinorhyncha, Priapulida, and Loricifera. These groups have a reduced coelom, called a pseudocoelom.

The remaining two groups of protostomes are sometimes grouped together as the Spiralia, since in both embryos develop with spiral cleavage.

Platyzoa

The Platyzoa include the phylum Platyhelminthes, the flatworms.[75] These were originally considered some of the most primitive Bilateria, but it now appears they developed from more complex ancestors.[76] A number of parasites are included in this group, such as the flukes and tapeworms.[75] Flatworms are acoelomates, lacking a body cavity, as are their closest relatives, the microscopic Gastrotricha.[77]

The other platyzoan phyla are mostly microscopic and pseudocoelomate. The most prominent are the Rotifera or rotifers, which are common in aqueous environments. They also include the Acanthocephala or spiny-headed worms, the Gnathostomulida, Micrognathozoa, and possibly the Cycliophora.[78] These groups share the presence of complex jaws, from which they are called the Gnathifera.

Lophotrochozoa

The Lophotrochozoa, evolved within Protostomia, include two of the most successful animal phyla, the Mollusca and Annelida.[79][80] The former, which is the second-largest animal phylum by number of described species, includes animals such as snails, clams, and squids, and the latter comprises the segmented worms, such as earthworms and leeches. These two groups have long been considered close relatives because of the common presence of trochophore larvae, but the annelids were considered closer to the arthropods because they are both segmented.[81] Now, this is generally considered convergent evolution, owing to many morphological and genetic differences between the two phyla.[82]

The Lophotrochozoa also include the Nemertea or ribbon worms, the Sipuncula, and several phyla that have a ring of ciliated tentacles around the mouth, called a lophophore.[83] These were traditionally grouped together as the lophophorates.[84] but it now appears that the lophophorate group may be paraphyletic,[85] with some closer to the nemerteans and some to the molluscs and annelids.[86][87] They include the Brachiopoda or lamp shells, which are prominent in the fossil record, the Entoprocta, the Phoronida, and possibly the Bryozoa or moss animals.[88]

Model organisms

Because of the great diversity found in animals, it is more economical for scientists to study a small number of chosen species so that connections can be drawn from their work and conclusions extrapolated about how animals function in general. Because they are easy to keep and breed, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans have long been the most intensively studied metazoan model organisms, and were among the first life-forms to be genetically sequenced. This was facilitated by the severely reduced state of their genomes, but as many genes, introns, and linkages lost, these ecdysozoans can teach us little about the origins of animals in general. The extent of this type of evolution within the superphylum will be revealed by the crustacean, annelid, and molluscan genome projects currently in progress. Analysis of the starlet sea anemone genome has emphasised the importance of sponges, placozoans, and choanoflagellates, also being sequenced, in explaining the arrival of 1500 ancestral genes unique to the Eumetazoa.[89]

An analysis of the homoscleromorph sponge Oscarella carmela also suggests that the last common ancestor of sponges and the eumetazoan animals was more complex than previously assumed.[90]

Other model organisms belonging to the animal kingdom include the house mouse (Mus musculus) and zebrafish (Danio rerio).

.jpg)

History of classification

Aristotle divided the living world between animals and plants, and this was followed by Carolus Linnaeus (Carl von Linné), in the first hierarchical classification.[91] Since then biologists have begun emphasizing evolutionary relationships, and so these groups have been restricted somewhat. For instance, microscopic protozoa were originally considered animals because they move, but are now treated separately.

In Linnaeus's original scheme, the animals were one of three kingdoms, divided into the classes of Vermes, Insecta, Pisces, Amphibia, Aves, and Mammalia. Since then the last four have all been subsumed into a single phylum, the Chordata, whereas the various other forms have been separated out. The above lists represent our current understanding of the group, though there is some variation from source to source.

See also

|

- Animal coloration

- Ethology

- Fauna

- List of animal names

- List of animals by number of neurons

- Lists of animals

- Lists of organisms by population

- Zoology

References

- ↑ Monster fish crushed opposition with strongest bite ever

- ↑ Cresswell, Julia (2010). The Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954793-7. "'having the breath of life', from anima 'air, breath, life' ."

- ↑ "Animals". Merriam-Webster's. Retrieved 16 May 2010. "2 a : one of the lower animals as distinguished from human beings b : mammal; broadly : vertebrate"

- ↑ "Animal". The American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company. 2006.

- ↑ "Panda Classroom". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ↑ Bergman, Jennifer. "Heterotrophs". Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ↑ Douglas, Angela E.; Raven, John A. (2003). "Genomes at the interface between bacteria and organelles". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 358 (1429): 5–17; discussion 517–8. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1188. PMC 1693093. PMID 12594915.

- ↑ Davidson, Michael W. "Animal Cell Structure". Archived from the original on 20 September 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ↑ Saupe, S. G. "Concepts of Biology". Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ↑ Minkoff, Eli C. (2008). Barron's EZ-101 Study Keys Series: Biology (2nd, revised ed.). Barron's Educational Series. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7641-3920-8.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Adam-Carr, Christine; Hayhoe, Christy; Hayhoe, Douglas; Hayhoe, Katharine (2010). Science Perspectives 10. Nelson Education Ltd. ISBN 978-0-17-635528-9.

- ↑ Hillmer, Gero; Lehmann, Ulrich (1983). Fossil Invertebrates. Translated by J. Lettau. CUP Archive. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-521-27028-1. ISSN 0266-3236.

- ↑ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science.

- ↑ Sangwal, Keshra (2007). Additives and crystallization processes: from fundamentals to applications. John Wiley and Sons. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-470-06153-4.

- ↑ Becker, Wayne M. (1991). The world of the cell. Benjamin/Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-0870-9.

- ↑ Magloire, Kim (2004). Cracking the AP Biology Exam, 2004–2005 Edition. The Princeton Review. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-375-76393-9.

- ↑ Knobil, Ernst (1998). Encyclopedia of reproduction, Volume 1. Academic Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-12-227020-8.

- ↑ Schwartz, Jill (2010). Master the GED 2011 (w/CD). Peterson's. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-7689-2885-3.

- ↑ Hamilton, Matthew B. (2009). Population genetics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4051-3277-0.

- ↑ Adiyodi, K. G.; Hughes, Roger N.; Adiyodi, Rita G. (2002). Reproductive Biology of Invertebrates, Progress in Asexual Reproduction, Volume 11. Wiley. p. 116.

- ↑ Kaplan (2008). GRE exam subject test. Kaplan Publishing. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-4195-5218-2.

- ↑ Tmh (2006). Study Package For Medical College Entrance Examinations. Tata McGraw-Hill. p. 6.22. ISBN 978-0-07-061637-0.

- ↑ Ville, Claude Alvin; Walker, Warren Franklin; Barnes, Robert D. (1984). General zoology. Saunders College Pub. p. 467. ISBN 978-0-03-062451-3.

- ↑ Hamilton, William James; Boyd, James Dixon; Mossman, Harland Winfield (1945). Human embryology: (prenatal development of form and function). Williams & Wilkins. p. 330.

- ↑ Philips, Joy B. (1975). Development of vertebrate anatomy. Mosby. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-8016-3927-2.

- ↑ The Encyclopedia Americana: a library of universal knowledge, Volume 10. Encyclopedia Americana Corp. 1918. p. 281.

- ↑ Romoser, William S.; Stoffolano, J. G. (1998). The science of entomology. WCB McGraw-Hill. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-697-22848-2.

- ↑ Rastogi, V. B. (1997). Modern Biology. Pitambar Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-209-0496-5.

- ↑ Levy, Charles K. (1973). Elements of Biology. Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-390-55627-1.

- ↑ Begon, M., Townsend, C., Harper, J. (1996). Ecology: Individuals, populations and communities (Third edition). Blackwell Science, London. ISBN 0-86542-845-X, ISBN 0-632-03801-2, ISBN 0-632-04393-8.

- ↑ predation. Britannica.com. Retrieved on 2011-11-23.

- ↑ Marchetti, Mauro; Rivas, Victoria (2001). Geomorphology and environmental impact assessment. Taylor & Francis. p. 84. ISBN 978-90-5809-344-8.

- ↑ Allen, Larry Glen; Pondella, Daniel J.; Horn, Michael H. (2006). Ecology of marine fishes: California and adjacent waters. University of California Press. p. 428. ISBN 978-0-520-24653-9.

- ↑ Clutterbuck, Peter (2000). Understanding Science: Upper Primary. Blake Education. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-86509-170-9.

- ↑ Gupta, P.K. Genetics Classical To Modern. Rastogi Publications. p. 26. ISBN 978-81-7133-896-2.

- ↑ Garrett, Reginald; Grisham, Charles M. (2010). Biochemistry. Cengage Learning. p. 535. ISBN 978-0-495-10935-8.

- ↑ New scientist (IPC Magazines) 152 (2050–2055): 105. 1996.

- ↑ Castro, Peter; Huber, Michael E. (2007). Marine Biology (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-07-722124-9.

- ↑ Campbell, Niel A. (1990). Biology (2nd ed.). Benjamin/Cummings Pub. Co. p. 560. ISBN 978-0-8053-1800-5.

- ↑ Richard R. Behringer, Alexander D. Johnson, Robert E. Krumlauf, Michael K. Levine, Nipam Patel, Neelima Sinha, ed. (2008). Emerging model organisms: a laboratory manual, Volume 1 (illustrated ed.). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-87969-872-0.

- ↑ Hall, Brian Keith; Hallgrímsson, Benedikt; Strickberger, Monroe W. (2008). Strickberger's evolution: the integration of genes, organisms and populations. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-7637-0066-9.

- ↑ Hamilton, Gina. Kingdoms of Life – Animals (ENHANCED eBook). Lorenz Educational Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4291-1610-7.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Maloof, Adam C.; Rose, Catherine V.; Beach, Robert; Samuels, Bradley M.; Calmet, Claire C.; Erwin, Douglas H.; Poirier, Gerald R.; Yao, Nan; Simons, Frederik J. (17 August 2010). "Possible animal-body fossils in pre-Marinoan limestones from South Australia". Nature Geoscience 3 (9): 653. Bibcode:2010NatGe...3..653M. doi:10.1038/ngeo934.

- ↑ Costa, James T.; Darwin, Charles (2009). The annotated Origin: a facsimile of the first edition of On the origin of species. Harvard University Press. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-674-03281-1.

- ↑ Schopf, J. William (1999). Evolution!: facts and fallacies. Academic Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-12-628860-5.

- ↑ Milsom, Clare; Rigby, Sue (2009). Fossils at a Glance. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-9336-8.

- ↑ Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. (2005). Biology (7th ed.). Pearson, Benjamin Cummings. p. 526. ISBN 978-0-8053-7171-0.

- ↑ Seilacher, Adolf; Bose, Pradip K.; Pfluger, Friedrich (1998). "Animals More Than 1 Billion Years Ago: Trace Fossil Evidence from India". Science 282 (5386): 80–83. Bibcode:1998Sci...282...80S. doi:10.1126/science.282.5386.80. PMID 9756480.

- ↑ Matz, Mikhail V.; Frank, Tamara M.; Marshall, N. Justin; Widder, Edith A.; Johnsen, Sönke (2008). "Giant Deep-Sea Protist Produces Bilaterian-like Traces". Current Biology 18 (23): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.028. PMID 19026540. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ↑ Reilly, Michael (20 November 2008). "Single-celled giant upends early evolution". MSNBC. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ↑ Ryan, JF; Pang, K; Comparative Sequencing Program, Nisc; Mullikin, James C; Martindale, Mark Q; Baxevanis, Andreas D (2010). "The homeodomain complement of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi suggests that Ctenophora and Porifera diverged prior to the ParaHoxozoa". Evodevo 1 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/2041-9139-1-9.

- ↑ Lehmann J, Stadler PF, Krauss V (2012) Near intron pairs and the metazoan tree. Mol Phylogenet Evol doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2012.11.012

- ↑ "The Genome of the Ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi and its Implications for Cell Type Evolution". Science 342 (6164). 13 December 2013. doi:10.1126/science.1242592.

- ↑ Bhamrah, H. S.; Juneja, Kavita (2003). An Introduction to Porifera. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. p. 58. ISBN 978-81-261-0675-2.

- ↑ Sumich, James L. (2008). Laboratory and Field Investigations in Marine Life. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7637-5730-4.

- ↑ Jessop, Nancy Meyer (1970). Biosphere; a study of life. Prentice-Hall. p. 428.

- ↑ Sharma, N. S. (2005). Continuity And Evolution Of Animals. Mittal Publications. p. 106. ISBN 978-81-8293-018-6.

- ↑ McGraw-Hill encyclopedia of science & technology: MET-NIC., Volume 11 (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill. 1997. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-07-911504-1. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ Dunn, Casey W. et al. (April 2008). "Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life". Nature 452 (7188): 745–9. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..745D. doi:10.1038/nature06614. PMID 18322464.

- ↑ Langstroth, Lovell; Langstroth, Libby (2000). Newberry, Todd, ed. A Living Bay: The Underwater World of Monterey Bay. University of California Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-520-22149-9.

- ↑ Safra, Jacob E. (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 16. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ↑ Kotpal, R. L. Modern Text Book of Zoology: Invertebrates. Rastogi Publications. p. 184. ISBN 978-81-7133-903-7.

- ↑ Peters, Kenneth E.; Walters, Clifford C.; Moldowan, J. Michael (2005). The Biomarker Guide: Biomarkers and isotopes in petroleum systems and Earth history 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 717. ISBN 978-0-521-83762-0.

- ↑ Safra, Jacob E. (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 1; Volume 3. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 767. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ↑ Valentine, James W. (July 1997). "Cleavage patterns and the topology of the metazoan tree of life". PNAS (The National Academy of Sciences) 94 (15): 8001–8005. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.8001V. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.15.8001. PMC 21545. PMID 9223303.

- ↑ Hyde, Kenneth (2004). Zoology: An Inside View of Animals. Kendall Hunt. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-7575-0997-1.

- ↑ Alcamo, Edward (1998). Biology Coloring Workbook. The Princeton Review. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-679-77884-4.

- ↑ Holmes, Thom (2008). The First Vertebrates. Infobase Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-8160-5958-4.

- ↑ Rice, Stanley A. (2007). Encyclopedia of evolution. Infobase Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8160-5515-9.

- ↑ Tobin, Allan J.; Dusheck, Jennie (2005). Asking about life. Cengage Learning. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-534-40653-0.

- ↑ Safra, Jacob E. (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 19. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 791. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (2005). The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-618-61916-0.

- ↑ Prewitt, Nancy L.; Underwood, Larry S.; Surver, William (2003). BioInquiry: making connections in biology. John Wiley. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-471-20228-8.

- ↑ Schmid-Hempel, Paul (1998). Parasites in social insects. Princeton University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-691-05924-2.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Gilson, Étienne (2004). El espíritu de la filosofía medieval. Ediciones Rialp. p. 384. ISBN 978-84-321-3492-0.

- ↑ Ruiz-Trillo, Iñaki; Riutort, Marta; Littlewood, D. Timothy J.; Herniou, Elisabeth A.; Baguña, Jaume (1999). "Acoel Flatworms: Earliest Extant Bilaterian Metazoans, Not Members of Platyhelminthes". Science 283 (5409): 1919–1923. Bibcode:1999Sci...283.1919R. doi:10.1126/science.283.5409.1919. PMID 10082465.

- ↑ Todaro, Antonio. "Gastrotricha: Overview". Gastrotricha: World Portal. University of Modena & Reggio Emilia. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- ↑ Kristensen, Reinhardt Møbjerg (2002). "An Introduction to Loricifera, Cycliophora, and Micrognathozoa". Integrative and Comparative Biology 42 (3): 641–651. doi:10.1093/icb/42.3.641. PMID 21708760.

- ↑ "Biodiversity: Mollusca". The Scottish Association for Marine Science. Archived from the original on 8 July 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ↑ Russell, Bruce J. (Writer), Denning, David (Writer) (2000). Branches on the Tree of Life: Annelids (VHS). BioMEDIA ASSOCIATES.

- ↑ Eernisse, Douglas J.; Albert, James S.; Anderson, Frank E. (1 September 1992). "Annelida and Arthropoda are not sister taxa: A phylogenetic analysis of spiralean metazoan morphology". Systematic Biology 41 (3): 305–330. doi:10.2307/2992569. JSTOR 2992569.

- ↑ Kim, Chang Bae; Moon, Seung Yeo; Gelder, Stuart R.; Kim, Won (1996). "Phylogenetic Relationships of Annelids, Molluscs, and Arthropods Evidenced from Molecules and Morphology". Journal of Molecular Evolution (New York: Springer) 43 (3): 207–215. doi:10.1007/PL00006079. PMID 8703086.

- ↑ Collins, Allen G. (1995). The Lophophore. University of California Museum of Paleontology.

- ↑ Adoutte, André; Balavoine, Guillaume; Lartillot, Nicolas; Lespinet, Olivier; Prud'Homme, Benjamin; De Rosa, Renaud (2000). "The new animal phylogeny: Reliability and implications". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (9): 4453–4456. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.4453A. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4453. PMC 34321. PMID 10781043.

- ↑ Passamaneck, Yale J. (2003). "Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics of the Metazoan Clade Lophotrochozoa. p. 124.

- ↑ Sundberg, Per; Turbeville, J. M.; Lindh, Susanne (2001). "Phylogenetic relationships among higher nemertean (Nemertea) taxa inferred from 18S rDNA sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 20 (3): 327–334. doi:10.1006/mpev.2001.0982. PMID 11527461.

- ↑ Boore, Jeffrey L.; Staton, Joseph L. (2002). "The mitochondrial genome of the Sipunculid Phascolopsis gouldii supports its association with Annelida rather than Mollusca" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution 19 (2): 127–137. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004065. PMID 11801741. Archived from the original on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ↑ Nielsen, Claus (2001). "Bryozoa (Ectoprocta: 'Moss' Animals)". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd). doi:10.1038/npg.els.0001613. ISBN 0-470-01617-5. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- ↑ Putnam, Nicholas H. et al. (2007). "Sea anemone genome reveals ancestral eumetazoan gene repertoire and genomic organization". Science 317 (5834): 86–94. Bibcode:2007Sci...317...86P. doi:10.1126/science.1139158. PMID 17615350.

- ↑ Xiujuan Wang; Lavrov, Dennis V. (27 October 2006). "Mitochondrial Genome of the homoscleromorph Oscarella carmela (Porifera, Demospongiae) Reveals Unexpected Complexity in the Common Ancestor of Sponges and Other Animals". Molecular Biology and Evolution 24 (2): 363–373. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl167. PMID 17090697.

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. (in Latin) (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

Bibliography

- Klaus Nielsen. Animal Evolution: Interrelationships of the Living Phyla (2nd edition). Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Knut Schmidt-Nielsen. Animal Physiology: Adaptation and Environment. (5th edition). Cambridge University Press, 1997.

External links

| Find more about Animalia at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| |

Definitions and translations from Wiktionary |

| |

Media from Commons |

| |

Quotations from Wikiquote |

| |

Source texts from Wikisource |

| |

Textbooks from Wikibooks |

| |

Learning resources from Wikiversity |

-

Data related to Animalia at Wikispecies

Data related to Animalia at Wikispecies - Animal at the Encyclopedia of Life

- Tree of Life Project

- Animal Diversity Web – University of Michigan's database of animals, showing taxonomic classification, images, and other information.

- ARKive – multimedia database of worldwide endangered/protected species and common species of UK.

- The Animal Kingdom

- Scientific American Magazine (December 2005 Issue) – Getting a Leg Up on Land About the evolution of four-limbed animals from fish.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||