Alsace-Lorraine

| Imperial territory of Alsace-Lorraine Reichsland Elsass-Lothringen | ||||||

| Province of the German Empire | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| Anthem Elsässisches Fahnenlied "The Alsatian Flag's song" | ||||||

| ||||||

| Capital | Straßburg | |||||

| Government | Province | |||||

| Reichsstatthalter | ||||||

| - | 1871–1879 | Eduard von Möller (first) | ||||

| - | 1918 | Rudolf Schwander (last) | ||||

| Legislature | Landtag | |||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism / World War I | |||||

| - | Treaty of Frankfurt | 10 May 1871 | ||||

| - | Disestablished | 1918 | ||||

| - | Treaty of Versailles | 28 June 1919 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | 1910 | 14,496 km2 (5,597 sq mi) | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 1910 | 1,874,014 | ||||

| Density | 129.3 /km2 (334.8 /sq mi) | |||||

| Today part of | | |||||

The Imperial territory of Alsace-Lorraine (German: Reichsland Elsass-Lothringen or Elsass-Lothringen), was a territory created by the German Empire in 1871 after it annexed most of Alsace and the Moselle region of Lorraine following its victory in the Franco-Prussian War. The Alsatian part lay in the Rhine Valley on the west bank of the Rhine River and east of the Vosges Mountains. The Lorraine section was in the upper Moselle valley to the north of the Vosges Mountains.

The Imperial territory of Alsace-Lorraine was made up of 93% of Alsace (7% remained French) and 26% of Lorraine (74% remained French). For historical reasons, specific legal dispositions are still applied in the territory in form of a local law. In relation to its special legal status, since its reversion to France following World War I, the territory has been referred to administratively as Alsace-Moselle.[1]

Geography

The Imperial territory of Alsace-Lorraine had a land area of 14,496 km2 (5,597 sq mi). Its capital was Strassburg. It was divided in three districts (Bezirke in German):

- Oberelsass, whose capital was Kolmar, had a land area of 3,525 km² and corresponds exactly to the current department of Haut-Rhin

- Unterelsass, whose capital was Strassburg, had a land area of 4,755 km² and corresponds exactly to the current department of Bas-Rhin

- Lothringen, whose capital was Metz, had a land area of 6,216 km² and corresponds exactly to the current department of Moselle

Towns and cities

The largest urban areas in Alsace-Lorraine at the 1910 census were:

- Strasbourg (Strassburg in German): 220,883 inhabitants

- Mulhouse (Mülhausen) : 128,190 inhabitants

- Metz: 102,787 inhabitants

- Thionville (Diedenhofen): 69,693 inhabitants

- Colmar (Kolmar): 44,942 inhabitants

History

Background

The modern history of Alsace-Lorraine was largely influenced by the rivalry between French and German nationalisms.

Since the Middle Ages, France sought to attain and preserve its "natural boundaries", which are the Pyrenees to the southwest, the Alps to the southeast, and the Rhine River to the northeast. These strategic aims led to the absorption of territories located west of the Rhine river. What is now known as Alsace was progressively conquered by Louis XIV in the 17th century, while Lorraine was integrated in the 18th century under Louis XV.[2]

The German nationalism which arose following the French occupation of Germany, sought to unify all the German-speaking populations of Europe in a single nation-state. As Alsace and Moselle (northern Lorraine) were mostly composed of German dialects speakers, these regions were coveted by the German Empire.

From annexation to World War I

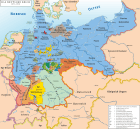

_Elsa%C3%9F-Lothringen.svg.png)

The newly created German Empire's demand of territory from France in the aftermath of its victory in the Franco-Prussian War was not simply a punitive measure. The transfer was controversial even among the Germans themselves - German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck was strongly opposed to a transfer of territory that he knew would provoke permanent French enmity towards the new State.[citation needed] However, German Emperor Wilhelm I eventually sided with Helmuth von Moltke the Elder and other Prussian generals and others who argued that a westward shift in the new Franco-German border was necessary and desirable for a number of reasons. From a nationalistic perspective, the transfer seemed justified, since most of the lands that were annexed were populated by people who spoke Alemannic German dialects. From a military perspective, shifting the Franco-German frontier away from the Rhine would give the Germans a strategic advantage over the French, especially by early 1870s military standards and thinking. Indeed, thanks to this annexation, the Germans took control of the fortifications of Metz, a French-speaking town, and also of most of the iron resources available in the region.

However, domestic politics of the new Empire might have been the decisive factor. Although it was effectively led by Prussia, the German Empire was a new and highly decentralized creation. The new arrangement left many senior Prussian generals with serious misgivings about leading diverse military forces to guard a pre-war frontier that, except for the northernmost section, was part of two other states of the new Empire – Baden and Bavaria. As recently as the 1866 Austro-Prussian War, these states had been Prussia's enemies. Both states, but especially Bavaria had been given substantial concessions with regards to local autonomy in the new Empire's constitution, including a great deal of autonomy over military matters. For this reason, the Prussian General Staff argued that it was prudent and necessary that the new Empire's frontier with France be under their direct control. Creating a new Imperial Territory (Reichsland) out of formerly French territory would achieve this goal: although a Reichsland would not be part of the Kingdom of Prussia, being governed directly from Berlin it would be under Prussian control. Thus, by annexing territory, Berlin was able to avoid delicate negotiations with Baden and Bavaria on such matters as construction and control of new fortifications, etc. The governments of Baden and Bavaria, naturally, were in favour of moving the French border away from their territories.

Memories of the Napoleonic Wars were still quite fresh in the 1870s. Right up until the Franco-Prussian War, the French had maintained a long-standing desire to establish their entire eastern frontier on the Rhine, and thus they were viewed by most 19th-century Germans as an aggressive people. In the years prior to 1870, it is arguable that the Germans feared the French more than the French feared the Germans. Many Germans at the time thought creation of the new Empire in itself would be enough to earn permanent French enmity, and thus desired a defensible border with their old enemy. Any additional enmity that would be earned from territorial concessions was downplayed as marginal and insignificant in the overall scheme of things.

The annexed area consisted of the northern part of Lorraine, along with Alsace. The area around the town of Belfort (now the French département of Territoire de Belfort) was unaffected, because its inhabitants were predominantly French speakers and because Belfort had been defended by Colonel Denfert-Rochereau, who surrendered only after receiving orders from Paris. The town of Montbéliard and its surrounding area to the south of Belfort, which have been part of the Doubs department since 1816, and therefore were not considered part of Alsace, were not included, despite the fact that they were a Protestant enclave, as it belonged to Württemberg from 1397 to 1806. This area corresponded to the French départements of Bas-Rhin (in its entirety), Haut-Rhin (except the area of Belfort and Montbéliard), and a small area in the northeast of the Vosges département, all of which made up Alsace, and the départements of Moselle (four-fifths of it) and the northeast of Meurthe (one-third of Meurthe), which were the eastern part of Lorraine.

The remaining département of Meurthe was joined with the westernmost part of Moselle which had escaped German annexation to form the new département of Meurthe-et-Moselle.

The new border between France and Germany mainly followed the geolinguistic divide between Romance and Germanic dialects, except in a few valleys of the Alsatian side of the Vosges mountains, the city of Metz and in the area of Château-Salins (formerly in the Meurthe département), which were annexed by Germany despite the fact that people there spoke French.[3] In 1900, 11.6% of the population of Alsace-Lorraine spoke French as mother language (11.0% in 1905, 10.9% in 1910).

The fact that small francophone areas were affected was used in France to denounce the new border as hypocrisy, since Germany had justified them by the native Germanic dialects and culture of the inhabitants, which was true for the majority of Alsace-Lorraine. However, the German administration was tolerant of the use of the French language, and French was permitted as an official language and school language in those areas where it was spoken by a majority.

The Treaty of Frankfurt gave the residents of the region until October 1, 1872 to choose between emigrating to France or remaining in the region and having their nationality legally changed to German. By 1876, about 100,000 or 5% of the residents of Alsace-Lorraine had emigrated to France.[4]

The "being French" feeling stayed strong at least during the first sixteen years of the annexation. During the Reichstag elections, the fifteen deputies of 1874, 1881, 1884 (but one) and 1887 were called protester deputies (fr: députés protestataires) because they expressed to the Parliament their opposition to the annexation by means of the 1874 motion in French language: « May it please the Reichstag to decide that the populations of Alsace-Lorraine that were annexed, without having been consulted, to the Germanic Empire by the treaty of Frankfurt have to come out particularly about this annexation. »[5] The infamous Saverne Affair put a severe strain on the relationship between the imperial state of Alsace-Lorraine and the remainder of the German Empire.

Under the German Empire of 1871-1918, the territory constituted the Reichsland or Imperial Province of Elsass-Lothringen. The area was administered directly by the imperial government in Berlin and was granted some measure of autonomy in 1911. This included its constitution and state assembly, its own flag, and the Elsässisches Fahnenlied as its anthem.

Reichstag election results 1874–1912

| 1874 | 1877 | 1878 | 1881 | 1884 | 1887 | 1890 | 1893 | 1898 | 1903 | 1907 | 1912 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhabitants (in 1,000) | 1550 | 1532 | 1567 | 1564 | 1604 | 1641 | 1719 | 1815 | 1874 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eligible voters (in %) | 20.6 | 21.6 | 21.0 | 19.9 | 19.5 | 20.1 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 21.0 | 21.7 | 21.9 | 22.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout (in %) | 76.5 | 64.2 | 64.1 | 54.2 | 54.7 | 83.3 | 60.4 | 76.4 | 67.8 | 77.3 | 87.3 | 84.9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conservatives (K) | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 14.7 | 10.0 | 4.8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deutsche Reichspartei (R) | 0.2 | 12.0 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 6.6 | 7.6 | 6.1 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 2.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National Liberal Party (N) | 2.1 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 11.5 | 8.5 | 3.6 | 10.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Liberals | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Freeminded Union (FVg) | 0.0 | 0.1 | 6.2 | 6.4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Progressive People's Party | 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 14.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Centre Party (Zentrum) (Z) | 0.0 | 0.6 | 7.1 | 31.1 | 5.4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Social Democratic Party of Germany (S) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 10.7 | 19.3 | 22.7 | 24.2 | 23.7 | 31.8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regional Parties (Autonomists) (Aut) | 96.9 | 97.8 | 87.5 | 93.3 | 95.9 | 92.2 | 56.6 | 47.7 | 46.9 | 36.1 | 30.2 | 46.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 12.0 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 0.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1874 | 1877 | 1878 | 1881 | 1884 | 1887 | 1890 | 1893 | 1898 | 1903 | 1907 | 1912 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mandates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FVp: Progressive People's Party. formed in 1910 as a merger of all leftist liberal parties.

During World War I

Alsace-Lorraine, during this time, was a geo-political prize contested between the French and German powers. The increased militarization of Europe, coupled with the lack of negotiation between major powers, led to harsh and rash actions taken by both parties in respect to Alsace-Lorraine.

As soon as war was declared, both the French and Germans used the inhabitants of Alsace-Lorraine as pawns in the growing conflict between France and Germany.

Alsatians living in France were arrested and placed into camps by the French authorities. Upon entering certain villages, veterans of the 1870 conflict were sought out and arrested.[6]

The Germans responded with similar atrocities:[7] the Saverne Affair had convinced the high command that the whole population was intensely hostile to the German Reich and that it should be terrorized into submission.

Due to the proximity of the front, German troops confiscated homes. The German military were highly suspicious of French patriots.

Whereas German authorities usually had been relatively tolerant with the use of French, they started to develop policies aimed at reducing the influence of French. French street names in Metz, which were displayed before in both languages, were suppressed on January 14, 1915. Six months later, on July 15, 1915, German became the only official language in the region,[8] leading to the Germanification of the towns’ names by an order of September 2, 1915.

Prohibiting the speaking of French in public further increased the exasperation of the natives, who were long accustomed to mixing their conversation with French language (see code-switching); however, the use even of one word, as innocent as "bonjour", could incur a fine.[9]

Ethnic Germans took part in the persecution as a way to demonstrate patriotism, listening closely and ready to denounce to the police anyone they heard using the prohibited language. Thus, the population was divided between an all-powerful minority and a majority which could only keep its fist in its pocket and wait for the hour of revenge.[10]

German authorities became increasingly worried about this renewed French patriotism, as Reichslands governor stated in February 1918: "Sympathies towards France and repulsion for Germans have penetrated to a scary depth the petty bourgeoisie and the peasantry".[11]

In order to spare them possible confrontations with relatives in France, the soldiers from Alsace-Lorraine were mainly sent to the Eastern front, or the Kaiserliche Marine.

In October 1918, the German Imperial Navy, which had spent most of the war since the Battle of Jutland in ports, was ordered to fight, in order to weaken the British Royal Navy for the time after the war. However, the sailors refused to obey. At that time, about 15,000 Alsatians and Lorrainers had been incorporated into the Kaiserliche Marine. Some of them joined the insurrection and the German Revolution, and decided to rouse their homeland to revolt against the monarchy of the Emperor.

Annexation to the French Republic

In the general revolutionary atmosphere of the expiring German Empire, Marxist councils of workers and soldiers (Soldaten und Arbeiterräte) formed in Mulhouse, in Colmar and Strasbourg in November 1918, in parallel to other such bodies set up in Germany, in imitation of the Russian equivalent soviets.

In this chaotic situation, Alsace-Lorraine's Landtag proclaimed itself the supreme authority of the land with the name of Nationalrat, the Soviet of Strasbourg claimed the foundation of a Republic of Alsace-Lorraine, while SPD Reichstag representative for Colmar, Jacques Peirotes, announced the establishment of the French rule, urging Paris to send troops quickly.[12]

While the soviet councils disbanded themselves with the departure of the German troops between November 11 and 17,[13] the arrival of the French Army stabilized the situation: French troops put the region under occupatio bellica and entered Strasbourg on November 21. The Nationalrat proclaimed the annexation of Alsace to France on December 5, even though this process did not gain international recognition until the signature of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

Alsace-Lorraine was divided into the départements of Haut-Rhin, Bas-Rhin and Moselle (the same political structure as before the annexation and as created by the French Revolution, with slightly different limits). Today, these territories enjoy laws that are significantly different from the rest of France – these specific provisions are known as the local law.

The département Meurthe-et-Moselle was maintained even after France recovered Alsace-Lorraine in 1919. The area of Belfort became a special status area and was not reintegrated into Haut-Rhin in 1919 but instead was made a full-status département in 1922 under the name Territoire-de-Belfort.[14]

The French Government immediately started a Francization campaign that included the forced deportation of all Germans who had settled in the area after 1870. For that purpose, the population was divided in four categories: A (French citizens prior to 1870), B (descendants of such French citizens), C (citizens of Allied or neutral states) and D (enemy aliens - Germans). Until July 1921 100,000 people categorized as "D" were expelled to Germany.[15][16] German-language Alsatian newspapers were also suppressed.

World War II

After France was defeated in the spring of 1940, Alsace and Moselle were not officially annexed by Germany, Adolf Hitler annexed them in 1940 through a law which he kept secret.[17] Through a series of laws which, individually, seemed minor, Berlin actually took the full control over Alsace-Moselle and could forcibly integrate Mosellan and Alsatian people into its army. Those territories were administered from Berlin until German defeat in 1945, when they were returned to France. During the occupation, Moselle was integrated into a Reichsgau named Westmark and Alsace was amalgamated with Baden. From 1942, people from Alsace and Moselle were made German citizens by the German government but, legally speaking, such de facto annexion was not accepted by international laws.[18]

Starting from October 1942, Alsatian and Mosellan men, especially young men, were enrolled by force into the German Nazi army either in the Wehrmacht, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine or Waffen-SS and they were called the malgré-nous which could be translated in English as the "unwillings" or the "against our will".[19][20][21] This was a major trauma for the two regions which had become "French-loving" after they reintegrated France after World War I. Though they were not included in the malgré nous expression, such situation also applied to eastern Belgium and Luxembourg.

Finally, 100,000 Alsatians and 30,000 Mosellans were enrolled especially to fight on the east front against Stalin's army. Most of them were interned in Tambov in Russia in 1945. Many others fought in Normandy as the malgré-nous of the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich.

Demographics

First language (1900)

- German: 1,492,347 (86.8%)[22]

- Other Languages: 219,638 (12.8%)[22]

- French: 198,318 (11.5%)

- Italian: 18,750 (1.1%)

- Polish: 1,410 (0.1%)

- German and a second language : 7,485 (0.4%)

Religion

When Alsace and the Lorrain department became part of Germany, the French laws regarding religious bodies were preserved, with special privileges to the then recognised religions of Calvinism, Judaism, Lutheranism and Roman Catholicism, under a system known as the Concordat. However, the Roman Catholic dioceses of Metz and of Strasbourg became exempt jurisdictions. The Church of Augsburg Confession of France, with its directory, supreme consistory and the bulk of its parishioners residing in Alsace, was reorganised as the Protestant Church of Augsburg Confession of Alsace and Lorraine (EPCAAL) in 1872, but territorially reconfined to Alsace-Lorraine only. The five local Calvinist consistories, originally part of the Reformed Church of France, formed a statewide synod in 1895, the Protestant Reformed Church of Alsace and Lorraine (EPRAL). The three Israelite consistories in Colmar, Metz and Strasbourg were disentangled from supervision by the Israelite Central Consistory of France and continued as separate statutory corporations which never formed a joint body, but cooperated. All the mentioned religious bodies retained the status as établissements publics de culte (public bodies of cult). When the new Alsace-Lorrain constitution of 1911 provided for a bicameral state parliament (Landtag of Alsace-Lorraine) each recognised religion was entitled to send a representative into the first chamber of the Landtag as ex officio members (the bishops of Strasbourg and of Metz, the presidents of EPCAAL and EPRAL, and a delegate of the three Israelite consistories).

Religious statistics in 1910

Population 1,874,014 :[22]

- Protestant: 21.78% (18.87% Lutherans, 2.91% Calvinists)

- Catholic: 76.22%

- Other Christian: 0.21%

- Jewish: 1.63%

- Atheist: 0.12%

Statistics (1866–2010)

| Year | Population | Cause of change |

|---|---|---|

| 1866 | 1,596,198 | – |

| 1875 | 1,531,804 | After incorporation into the German Empire, 100,000 to 130,000 people left for France and French Algeria |

| 1910 | 1,874,014 | +0.58% population growth per year during 1875-1910 |

| 1921 | 1,709,749 | Death of young men in the German army, Deportation of German newcomers to Germany by the French authorities |

| 1936 | 1,915,627 | +0.76% population growth per year during 1921–1936 |

| 1946 | 1,767,131 | Death of young men in the French army in 1939–45, Death of young men in the German army in 1942–45, Death of civilians and many people still refugees in the rest of France |

| 1975 | 2,523,703 | +1.24% population growth per year during 1946–1975, a period of rapid population and economic growth in France known as the Trente Glorieuses |

| 2010 | 2,890,753 | +0.39% population growth per year during 1975–2010, a period marked by deindustrialization, rising unemployment (particularly in Moselle), and the migration of many people from northern and north-eastern France to the milder winters and economic dynamism of the Mediterranean and Atlantic regions of France |

Languages

Both Germanic and Romance dialects were traditionally spoken in Alsace-Lorraine before the 20th century.

Germanic dialects:

- Central German dialects:

- Luxembourgish Franconian in the north-west of Moselle (Lothringen) around Thionville (Diddenuewen in the local Luxembourgish dialect) and Sierck-les-Bains (Siirk in the local Luxembourgish dialect)

- Moselle Franconian in the central northern part of Moselle around Boulay-Moselle (Bolchin in the local Moselle Franconian dialect) and Bouzonville (Busendroff in the local Moselle Franconian dialect)

- Rhine Franconian in the north-east of Moselle around Forbach (Fuerboch in the local Rhine Franconian dialect), Bitche (Bitsch in the local Rhine Franconian dialect), and Sarrebourg (Saarbuerj in the local Rhine Franconian dialect), as well as in the north-west of Alsace around Sarre-Union

- Transitional between Central German and Upper German:

- South Franconian in the northernmost part of Alsace around Wissembourg (Waisseburch in the local South Franconian dialect)

- Upper German dialects:

- Alsatian in the largest part of Alsace and in a few villages in the extreme east of Moselle. Alsatian was the most spoken dialect in Alsace-Lorraine.

- High Alemannic in the southernmost part of Alsace, around Saint-Louis and Ferrette (Pfirt in the local High Alemannic dialect)

Romance dialects (belonging to the langues d'oïl like French):

- Lorrain in roughly the southern half of Moselle, including its capital Metz, as well as in some valleys of the Vosges Mountains in the west of Alsace around Schirmeck and Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines

- Franc-Comtois in 12 villages in the extreme south-west of Alsace

See also

Notes

- ↑ An instruction dated 8.14.1920 from the assistant Secretary of State of the Presidency of the Council to the General Commissioner of the Republic in Strasbourg reminds that the term Alsace-Lorraine is prohibited and must be replaced by the sentence "the département of Haut-Rhin, the département of Bas-Rhin and the département of Moselle". While this sentence was considered as too long, some used the term Alsace-Moselle to point to the three concerned départements. But, this instruction has no legal status because it is not based on any territorial authority.

- ↑ William Roosen, The age of Louis XIV: the rise of modern diplomacy. p. 55

- ↑ In fact, the linguistic border ran on the north of the new one, including in the "Alemannic" territories Thionville (also named Diedenhofen under the German Reich), Metz, Château-Salins, Vic-sur-Seille and Dieuze, which were fully French-speaking. The valleys of Orbey and Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines were in the same case. Similarly, the town of Dannemarie (and adjoining areas) were also left in Alsace when language alone could have made them part of Territoire de Belfort.

- ↑ http://www.mtholyoke.edu/~jihazel/pol116/annexation.html

- ↑ Les députés "protestataires" d'Alsace-Lorraine (French)

- ↑ In 1914, Albert Schweitzer was put under supervision in Lambaréné (then in French Equatorial Africa); in 1917, he was taken to France and incarcerated until July 1918.

- ↑ Charles Spindler, L'Alsace pendant la Guerre, 6 septembre 1914 and 11 septembre 1915.

- ↑ Grandhomme, Jean-Noël (2008) Boches ou tricolores. Strasbourg: La nuée bleue.

- ↑ As of on October 26, 1914, we can read in Spindler's journal: "Then he recommends to me not to speak French. The streets are infested with informers, men and women, who touch rewards and make arrest the passers by for a simple « merci » said in French. It goes without saying that these measures excite the joker spirit of the people. A woman at the market, who probably was unaware that "bonchour" and "merci" was French, is taken with part by a German woman because she answered her "Guten Tag" by a "bonchour ". Then, the good woman, the fists on the hips, challenges her client : "Now I'm fed up with your silly stories! Do you know what? [here something like "kiss my ..."]! Is that endly also French? » (als: Jetz grad genua mit dene dauwe Plän! Wisse Sie was? Leeke Sie mich ...! Esch des am End au franzêsch?)"

- ↑ We can read in L'Alsace pendant la guerre how the exasperation of the population gradually increased but Spindler hears, as of on September 29, 1914, a characteristic sentence: « ... the interior decorator H., who repairs the mattresses of the Ott house, said to me this morning: “If only it was the will of God that we became again French and that these damned "Schwowebittel" were thrown out of the country! And then, you know, there are chances that it happens.” It is the first time since the war I hear a simple man expressing frankly this wish. »

- ↑ Grandhomme, Jean-Noël. op.cit.

- ↑ Jacques Fortier, « La chute de l'Empire », Dernières Nouvelles d'Alsace, 16 november 2008 (Fr.)

- ↑ Jean-Noël Grandhomme, « Le retour de l'Alsace-Lorraine », L'Histoire, number 336, november 2008 (Fr.)

- ↑ However on the Colmar prefecture building, the name of Belfort can be seen as a sous-prefecture.

- ↑ Douglas, R.M. (2012). Ordnungsgemäße Überführung - Die Vertreibung der Deutschen nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg (in German). C.H.Beck. pp. 94 f. ISBN 978-3-406-62294-6.

- ↑ "Tabellarische Geschichte Elsaß-Lothringens / Französische Besatzung (1918-1940)". Archived from the original on 2009-10-25.

- ↑ Eberhard Jäckel, La France dans l'Europe de Hitler, op. cit., p. 123-124.

- ↑ Eberhard Jäckel, « L'annexion déguisée », dans Frankreich in Hitlers Europa – Die deutsche Frankreichpolitik im Zweiten Weltkrieg, Deutsche Verlag-Anstalg GmbH, Stuttgart, 1966, p. 123-124.

- ↑ The term actually appeared after World War I for the soldiers who did not have the choice to choose their camp.

- ↑ Pierre Schlund, Souvenirs de guerre d'un Alsacien, Éditions Mille et une vies, 2011,

- ↑ Paul Durand, En passant par la Lorraine ; gens et choses de chez nous 1900-1945, Éditions Le Lorrain, 1945, p. 131-132

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Statistics on verwaltungsgeschichte.de

Further reading

- Höpel, Thomas: The French-German Borderlands: Borderlands and Nation-Building in the 19th and 20th Centuries, European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2010, retrieved: December 17, 2012.

- Putnam, Ruth. Alsace and Lorraine from Cæsar to Kaiser, 58 B.C.–1871 A.D. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1915.

- Roth, François. Alsace-Lorraine, De 1870 À Nos Jours: Histoire d'un "pays perdu". Nancy: Place Stanislas, 2010. ISBN 978-2-35578-050-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alsace-Lorraine. |

- http://www.geocities.com/bfel/geschichte5b.html (Archived 2009-10-25) (German)

- http://www.elsass-lothringen.de/ (German)

- http://web.archive.org/web/20090730200508/http://geocities.com/CapitolHill/Rotunda/2209/Alsace_Lorraine.html

- France, Germany and the Struggle for the War-making Natural Resources of the Rhineland

- Elsass-Lothringen video

- Annuary of Cultur and Artists from Elsass-Lothringen (French) (German)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 48°40′N 7°00′E / 48.67°N 7°E