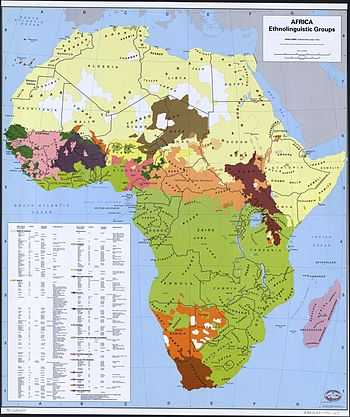

Africans

Afro-Asiatic

Hamitic (Berber, Cushitic) + Semitic (Ethiopian, Arabic)

Hausa (Chadic)

Niger Congo

Bantu

"Guinean" (Volta-Niger, Kru)

"Western Bantoid" (Senegambian, Bak)

"Central Bantoid" (Gur)

"Eastern Bantoid" (Southern Bantoid)

Mande

Nilo-Saharan (unity doubtful)

Nilotic

Central Sudanic+Eastern Sudanic

Kanuri

Songhai

other

Khoi-San (unity doubtful; Khoikhoi, San, Sandawe, Hadza)

Malayo-Polynesian (Malagasy)

Indo-European (Afrikaaner)

Africans are natives or inhabitants of Africa and people of African descent.[1][2][3]

The people of Africa

The African continent is home to many different ethnic groups, with wide-ranging phenotypical traits, both indigenous and foreign to the continent.[4] Many of these populations have diverse origins, with differing cultural, linguistic, and social traits. Distinctions within Africa's geography, such as the varying climates across the continent, have also served to nurture diverse lifestyles among its various populations. The continent's inhabitants live amid deserts and jungles, as well as in modern cities across the continent.

Prehistoric populations

In paleoanthropology, the recent African origin of modern humans, frequently dubbed the Out-of-Africa theory, is the most widely accepted model describing the geographic origin and early migration of anatomically modern humans.[5] The theory is called the (Recent) Out-of-Africa model in the popular press, and academically the recent single-origin hypothesis (RSOH), Replacement Hypothesis, and Recent African Origin (RAO) model. The concept was speculative until the 1980s, when it was supported by a study of present-day mitochondrial DNA, combined with evidence based on physical anthropology of archaic specimens.

Genetic studies and fossil evidence suggest that archaic Homo sapiens evolved to anatomically modern humans in Africa, between 200,000 and 150,000 years ago,[6] that members of one branch of Homo sapiens left the continent by between 125,000 and 60,000 years ago, and that over time these humans replaced earlier human populations such as Neanderthals and Homo erectus.[7] The date of the earliest successful Out-of-Africa migration (earliest migrants with living descendants) has generally been placed at 60,000 years ago as suggested by genetics, although migration out of the continent may have taken place as early as 125,000 years ago according to Arabian archaeology finds of tools in the region.[8] A 2013 paper reported that a previously unknown lineage had been found, which pushed the estimated date for the most recent common ancestor (Y-MRCA) back to 338,000 years ago.[9]

The recent single origin of modern humans in East Africa is the predominant position held within the scientific community.[10][11][12][13][14] There are differing theories on whether there was a single exodus or several. A multiple dispersal model involves the Southern Dispersal theory,[15] which has gained support in recent years from genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence. A growing number of researchers also suspect that "long-neglected North Africa" was the original home of the modern humans who first trekked out of the continent.[16][17][18]

The major competing hypothesis is the multiregional origin of modern humans, which envisions a wave of Homo sapiens migrating earlier from Africa and interbreeding with local Homo erectus populations in multiple regions of the globe. Most multiregionalists still view Africa as a major wellspring of human genetic diversity, but allow a much greater role for hybridization.[19][20]

Indigenous peoples and ancient settlers

The population of North Africa in ancient times consisted predominantly of Berbers in the West and Egyptians in the East. The Semitic Phoenicians and Jews, the Iranian Alans, and the European Greeks, Romans and Vandals settled in North Africa as well. Berber speaking populations constitute significant communities within Morocco (including Western Sahara) and Algeria and are also still present in smaller numbers in Tunisia, Libya and Mauritania. The Tuareg and other often-nomadic peoples are the principal inhabitants of the Saharan interior of North Africa. The Nubians, who developed an ancient civilization in the Nile Valley of North Africa, are among the predominately Nilo-Saharan-speaking groups found in Sudan, in addition to the Fur, Zaghawa and Masalit, among others.

In the Horn of Africa, most populations speak Afro-Asiatic languages. Certain Ethiopian and Eritrean groups (like the Amhara and Tigray-Tigrinya people, collectively known as "Habesha") speak Semitic languages. The Oromo, Afar, Beja and Somali peoples speak Cushitic languages, but some Somali clans claim Arab descent.[21]

Speakers of Niger-Congo languages from branches other than Bantu predominate in West Africa, with the Yoruba, Igbo, Fulani and Wolof ethnic groups among the largest. There are also Chadic-speaking West Africans in northerly areas bordering the Sahara, most predominately the Hausa. There are also small numbers of Nilo-Saharan speaking Africans such as the Kanuri, Songhai, Zarma and others in the easternmost parts of West Africa bordering Central Africa.

Bantu languages are most prominent in Central Africa and Southern Africa due to the Bantu expansion from West Africa, most significantly Kongo, Mongo, Luba, Xhosa, Zulu and Shona. However, Ubangian and Nilo-Saharan languages are also prominent in Central Africa: the Shilluk,[22] Dinka,[22] and the Nuer[22] predominate in eastern Central Africa while the Nilo-Saharan Kanuri predominate in western Central Africa. In northern Central Africa the Niger-Congo Ubangian Gbaya, Zande and Banda. There are also a few remaining indigenous Khoisan ("San" or "Bushmen") and Pygmy peoples in southern and central Africa, respectively.

In Southeast Africa, Niger-Congo languages are most widely spoken, especially those from the Bantu branch like Kikuyu, Makua and Kamba. Nilo-Saharan languages, such as Luo, Kalenjin and Maasai, are also spoken in lesser numbers. Swahili, with at least 80 million speakers (as a first or second language), is an important trade language in the Great Lakes area, and has official status in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda.

In the Kalahari Desert of Southern Africa, the distinct people known as the Bushmen (also "San", closely related to, but distinct from "Hottentots") have long been present. The San are physically distinct from other Africans and are the pre-Bantu indigenous people of southern Africa. Pygmies are the pre-Bantu indigenous peoples of central Africa.

Migrations

Arab

The Arabs arrived from Asia in the seventh century, introducing the Arabic language, and Islam to North Africa. Over several centuries, the majority of the indigenous African population of the region became Arabized by adopting the Arabic language, and developing a common identity with other peoples throughout the Arab World. Today, the majority of North Africans are Arabic-speaking, although the Berber language still predominates among Berber communities in certain areas. Sudan and Mauritania are divided between a mostly Arabized north and a Nilotic south. The Nubians have also been partly Arabized, although their original language is still in use.

In East Africa, some areas, particularly the island of Zanzibar and the Kenyan island of Lamu, received Arab Muslim and Southwest Asian settlers and merchants throughout the Middle Ages and even in antiquity. This gave birth to the Swahili culture.

European

Despite having a presence in Africa since Greek and Roman times, it was not until the sixteenth century that Europeans such as the Portuguese and Dutch began to establish trading posts and forts along the coasts of western and southern Africa. Eventually, a large number of Dutch augmented by French Huguenots and Germans settled in what is today South Africa. Their descendants, the Afrikaners and the Coloureds, are the largest European-descended groups in Africa today. In the nineteenth century, a second phase of colonization brought a large number of French and British settlers to Africa. The Portuguese settled mainly in Angola, but also in Mozambique. The Italians settled in Libya, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia. The French settled in large numbers in Algeria where they became known collectively as pieds-noirs, and on a smaller scale in other areas of North and West Africa as well as in Madagascar. The British settled chiefly in South Africa as well as the colony of Rhodesia, and in the highlands of what is now Kenya. Germans settled in what is now Tanzania and Namibia, and there is still a population of German-speaking white Namibians. Smaller numbers of European soldiers, businessmen, and officials also established themselves in administrative centers such as Nairobi and Dakar. Decolonization from the 1960s onwards often resulted in the mass emigration of European-descended settlers out of Africa — especially from Algeria, Angola, Kenya and Rhodesia. However, in South Africa and Namibia, the white minority remained politically dominant after independence from Europe, and a significant population of Europeans remained in these two countries even after democracy was finally instituted at the end of the Cold War. South Africa has also become the preferred destination of white Anglo-Zimbabweans, and of migrants from all over southern Africa.

Indian

European colonisation also brought sizable groups of Asians, particularly people from the Indian subcontinent, to British colonies. Large Indian communities are found in South Africa, and smaller ones are present in Kenya, Tanzania, and some other southern and east African countries. The large Indian community in Uganda was expelled by the dictator Idi Amin in 1972, though many have since returned. The islands in the Indian Ocean are also populated primarily by people of South Asian origin, often mixed with Africans and Europeans.[23]

The Malagasy of Madagascar are an Austronesian people, but those along the coast are generally mixed with Bantu, Arab, Indian and European populations. Malay and Indian ancestries are also important components in the group of people known in South Africa as Cape Coloureds (people with origins in two or more races and continents). In Mauritius, a tiny island in the Indian Ocean that is included in the African continent, Indian people form a majority.

Other

During the past century or so, small but economically important colonies of Lebanese[24] and Chinese[25] have also developed in the larger coastal cities of West and Southeast Africa, respectively.[26]

Decolonization

Decolonization has left some nations in power and marginalized others.

Conflicts with ethnic aspects taking place in Africa since decolonization include:

- Dervish state (1896–1920)

- Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1960)

- Zanzibar Revolution (1964)

- First and Second Chimurenga (1896–1897)(1966–1980)

- Casamance Conflict (since 1990)

- Conflict in the Niger Delta (since 1990)

- Insurgency in Ogaden (since 1995)

- Second Congo War (1998–2003)

- War in Darfur (since 2003)

- Kivu conflict (since 2004)

- Civil war in Chad (since 2005)

- Second Tuareg Rebellion (since 2007)

Contemporary demographics

Total population of Africa is estimated at 1 billion as of 2009.

See also

- List of African ethnic groups

- List of topics related to Black and African people

- Africans of European ancestry

- African diaspora

- Pan-Africanism

References

- ↑ "African". Cambridge Dictionaries Online. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ "Oxford Dictionaries".

- ↑ "The Free Dictionary".

- ↑ American Numismatic Association, The Numismatist, Volume 109, Issues 1-6 (American Numismatic Association: 1996), p. 43.

- ↑ McBride B, Haviland WE, Prins HEL, Walrath D (2009). The Essence of Anthropology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-495-59981-4.

- ↑ Reid GBR, Hetherington R (2010). The climate connection: climate change and modern human evolution. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-521-14723-9.

- ↑ Meredith M (2011). Born in Africa: The Quest for the Origins of Human Life. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-58648-663-2.

- ↑ Armitage SJ, Jasim SA, Marks AE, Parker AG, Usik VI, Uerpmann HP (January 2011). "The southern route "out of Africa": evidence for an early expansion of modern humans into Arabia". Science 331 (6016): 453–6. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..453A. doi:10.1126/science.1199113. PMID 21273486.

- ↑ Mendez, Fernando; Krahn, Thomas; Schrack, Bonnie; Krahn, Astrid-Maria; Veeramah, Krishna; Woerner, August; Fomine, Forka Leypey Mathew; Bradman, Neil; Thomas, Mark; Karafet, Tatiana; Hammer, Michael (2013). "An African American Paternal Lineage Adds an Extremely Ancient Root to the Human Y Chromosome Phylogenetic Tree". The American Journal of Human Genetics. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.02.002.

- ↑ Liu H, Prugnolle F, Manica A, Balloux F (August 2006). "A geographically explicit genetic model of worldwide human-settlement history". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79 (2): 230–7. doi:10.1086/505436. PMC 1559480. PMID 16826514. "Currently available genetic and archaeological evidence is supportive of a recent single origin of modern humans in East Africa. However, this is where the consensus on human settlement history ends, and considerable uncertainty clouds any more detailed aspect of human colonization history."

- ↑ "This week in Science: Out of Africa Revisited". Science 308 (5724): 921. 2005-05-13. doi:10.1126/science.308.5724.921g.

- ↑ Stringer C (June 2003). "Human evolution: Out of Ethiopia". Nature 423 (6941): 692–3, 695. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..692S. doi:10.1038/423692a. PMID 12802315.

- ↑ Johanson D. "Origins of Modern Humans: Multiregional or Out of Africa?". ActionBioscience. American Institute of Biological Sciences.

- ↑ "Modern Humans – Single Origin (Out of Africa) vs Multiregional".

- ↑ Searching for traces of the Southern Dispersal, by Dr. Marta Mirazón Lahr, et al.

- ↑ Balter M (January 2011). "Was North Africa the launch pad for modern human migrations?". Science 331 (6013): 20–3. Bibcode:2011Sci...331...20B. doi:10.1126/science.331.6013.20. PMID 21212332.

- ↑ Cruciani F, Trombetta B, Massaia A, Destro-Bisol G, Sellitto D, Scozzari R (June 2011). "A revised root for the human Y chromosomal phylogenetic tree: the origin of patrilineal diversity in Africa". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88 (6): 814–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.002. PMC 3113241. PMID 21601174.

- ↑ Smith TM, Tafforeau P, Reid DJ, Grün R, Eggins S, Boutakiout M, Hublin JJ (April 2007). "Earliest evidence of modern human life history in North African early Homo sapiens". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (15): 6128–33. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.6128S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700747104. PMC 1828706. PMID 17372199.

- ↑ Robert Jurmain; Lynn Kilgore; Wenda Trevathan (20 March 2008). Essentials of Physical Anthropology. Cengage Learning. pp. 266–. ISBN 978-0-495-50939-4. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ↑ Wolpoff MH, Hawks J, Caspari R (May 2000). "Multiregional, not multiple origins". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 112 (1): 129–36. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(200005)112:1<129::AID-AJPA11>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 10766948.

- ↑ Robin Hallett, Africa to 1875: A Modern History (University of Michigan Press: 1970), p. 105.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "The World Factbook: South Sudan". World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ Réunion Island

- ↑ Ivory Coast - The Levantine Community

- ↑ Chinese flocking in numbers to a new frontier: Africa

- ↑ Lebanese Immigrants Boost West African Commerce

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ethnic groups in Africa. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||