'Salem's Lot

| 'Salem's Lot | |

|---|---|

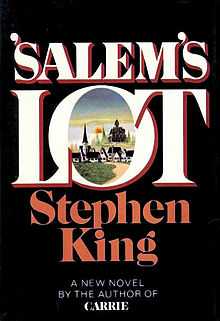

First edition cover | |

| Author | Stephen King |

| Country | U.S. |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Gothic fiction |

| Published | October 17, 1975 (Doubleday) |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| Pages | 439 |

| ISBN | 978-0-385-00751-1 |

'Salem's Lot is a 1975 horror fiction novel written by the American author Stephen King. It was his second published novel. The story involves a writer named Ben Mears who returns to the town where he lived as a boy between the ages of 9 through 13 (Jerusalem's Lot, or 'Salem's Lot for short) in Maine to discover that the residents are all becoming vampires. The town would be a location that would be revisited in the short stories "Jerusalem's Lot" and "One for the Road", both from King's 1978 short story collection Night Shift. The novel was nominated for the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel in 1976.[1] In 1987, it was nominated for the Locus Award as the All-Time Best Fantasy Novel.[2]

The title King originally chose for his book was Second Coming, but he later decided on Jerusalem's Lot. King stated the reason being that his wife, novelist Tabitha King, thought the original title sounded too much like a "bad sex story". King's publishers then shortened it to the current title, thinking the author's choice sounded too religious. 'Salem's Lot has been adapted into a television mini-series twice, first in 1979 and then in 2004. It was also adapted by the BBC as a seven part radio play in 1995.

In two separate interviews, King said that of all his books, 'Salem's Lot was his favorite. In his June 1983 Playboy interview, the interviewer mentioned that because it was his favorite, King was planning a sequel,[3] but he has more recently said on his website that since The Dark Tower series already picked up the story in the novels Wolves of the Calla and Song of Susannah, he felt there was no longer a need for one.[4] In 1987 he told Phil Konstantin in The Highway Patrolman magazine: "In a way it is my favorite story, mostly because of what it says about small towns. They are kind of a dying organism right now. The story seems sort of down home to me. I have a special cold spot in my heart for it!"[5]

The book is dedicated to King's daughter Naomi: "For Naomi Rachel King . . . promises to keep."

Plot

Ben Mears, a writer who grew up in Jerusalem's Lot, Maine, has returned home after twenty-five years. He quickly becomes friends with high school teacher Matt Burke and strikes up a passionate romantic relationship with Susan Norton, a young college graduate.

Ben starts writing a book about the Marsten House, an abandoned house where he had a bad experience as a child. Mears learns that the Marsten House—the former home of Depression-era hitman Hubert "Hubie" Marsten—has been purchased by Kurt Barlow, an Austrian immigrant who has arrived in the Lot ostensibly to open a store. Barlow is on an extended buying trip; only his business partner, Richard Straker, is seen in public.

The duo's arrival coincides with the disappearance of a young boy, Ralphie Glick, and the death of his brother Danny, who becomes the town's first vampire, infecting such locals as Mike Ryerson, Randy McDougall, Jack Griffen, and Danny's own mother, Marjorie Glick. Danny fails, however, to infect Mark Petrie, who resists him successfully by holding a plastic cross in Danny's face. Within several weeks many of the townspeople are turned into vampires.

Ben Mears and Susan are joined by Matt Burke and his doctor, Jimmy Cody, along with young Mark Petrie and the local priest, Father Callahan, in an effort to fight the spread of new vampires. Susan is captured by Barlow before Mark has a chance to rescue her. Susan becomes a vampire, and is eventually staked through the heart by Mears, the man who loved her.

Mark's parents are killed next, but Barlow does not infect them, so they are later given a clean burial. Barlow holds Mark and Father Callahan hostage, but Father Callahan has the upper hand, securing Mark's release, agreeing to Barlow's demand that he toss aside his cross and face him on equal terms. However he delays throwing the cross aside and the once powerful religious symbol loses its strength until Barlow can not only approach Callahan but break the cross, now nothing more than two small pieces of plaster, into bits. Barlow says "Sad to see a man's faith fail him", Callahan then has to drink blood from Barlow's neck. Callahan resists but is forced to drink, leaving him in a netherworld, as Barlow has left his mark. When Callahan tries to re-enter his church he receives an electric shock, preventing him from going inside. Callahan never goes near another church again.

Jimmy Cody is killed when he falls from a rigged staircase and is impaled by knives set up by the one-time denizens of Eva Miller's boarding house, Mears' one-time residence, who have now all become vampires. Ben Mears and Mark Petrie succeed in destroying the master vampire Barlow, but are lucky to escape with their lives and are forced to leave the town to the now leaderless vampires.

The novel's prologue, which is set shortly after the end of the story proper, describes the Ben and Mark's flight across the country to a seaside town in Mexico, where they attempt to recover from their ordeal. Mark is received into the Catholic Church by a friendly local priest and confesses for the first time what they have experienced.

The epilogue has the two returning to the town a year later, intending to renew the battle. Ben, knowing that there are too many hiding places for the vampires, deliberately starts a brush fire in the woods near the town with the intent of destroying it and the Marsten House once and for all.

Background

While teaching a high school Fantasy and Science Fiction course at Hampden Academy, King was inspired by Dracula, one of the books covered in the class. "One night over supper I wondered aloud what would happen if Dracula came back in the twentieth century, to America. 'He'd probably be run over by a Yellow Cab on Park Avenue and killed,' my wife said. (In the Introduction to the 2004 audiobook recording that Stephen King read himself, he says it was he who said "Probably he'd land in New York and be killed by a Taxi Cab, like Margaret Mitchell in Atlanta", and it was his wife who suggested a rural setting for the book.[6]) That closed the discussion, but in the following days, my mind kept returning to the idea. It occurred to me that my wife was probably right — if the legendary Count came to New York, that is. But if he were to show up in a sleepy little country town, what then? I decided I wanted to find out, so I wrote 'Salem's Lot, which was originally titled Second Coming".[7]

King expands on this thought in his essay for Adeline Magazine, "On Becoming a Brand Name" (February 1980): "I began to turn the idea over in my mind, and it began to coalesce into a possible novel. I thought it would make a good one, if I could create a fictional town with enough prosaic reality about it to offset the comic-book menace of a bunch of vampires."

Politics during the time influenced King's writing of the story. The corruption in the government was a significant factor in the inspiration of the story. "I wrote 'Salem's Lot during the period when the Ervin committee was sitting. That was also the period when we first learned of the Ellsberg break-in, the White House tapes, the connection between Gordon Liddy and the CIA, the news of enemies' lists, and other fearful intelligence. During the spring, summer and fall of 1973, it seemed that the Federal Government had been involved in so much subterfuge and so many covert operations that, like the bodies of the faceless wetbacks that Juan Corona was convicted of slaughtering in California, the horror would never end ... Every novel is to some extent an inadvertent psychological portrait of the novelist, and I think that the unspeakable obscenity in 'Salem's Lot has to do with my own disillusionment and consequent fear for the future. "In a way, it is more closely related to Invasion of the Body Snatchers than it is to Dracula. The fear behind 'Salem's Lot seems to be that the Government has invaded everybody." [8]

King first wrote of Jerusalem's Lot in a his short story "Jerusalem's Lot" of the same title, penned in college (but published years later for the first time in the anthology collection Night Shift).

In his non-fiction book, Danse Macabre, King recalls a dream he had when he was eight years old. In the dream, he saw the body of a hanged man dangling from the arm of a scaffold on a hill. "The corpse bore a sign: ROBERT BURNS. But when the wind caused the corpse to turn in the air, I saw that it was my face - rotted and picked by birds, but obviously mine. And then the corpse opened its eyes and looked at me. I woke up screaming, sure that a dead face would be leaning over me in the dark. Sixteen years later, I was able to use the dream as one of the central images in my novel 'Salem's Lot. I just changed the name of the corpse to Hubie Marsten." King's paperback publisher bought the book for $550,000.

In a 1969 installment of "The Garbage Truck", a column King wrote for the University of Maine at Orono's campus newspaper, King foreshadowed the coming of 'Salem's Lot by writing: "In the early 1800s a whole sect of Shakers, a rather strange, religious persuasion at best, disappeared from their village (Jeremiah's Lot) in Vermont. The town remains uninhabited to this day."[9]

In addition to Dracula, Shirley Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House (the opening passage of which King employed as an epigraph for Part One of his novel) and Grace Metalious' Peyton Place are often cited as inspirations for 'Salem's Lot.

Illustrated edition

In 2005, Centipede Press released a deluxe limited edition of 'Salem's Lot with black and white photographs by Jerry Uelsmann and the two short stories "Jerusalem's Lot" and "One for the Road", as well as over fifty pages of deleted material. The book was limited to 315 copies, each signed by Stephen King and Jerry Uelsmann. The book was printed on 100# Mohawk Superfine paper, it measured 9 by 13 inches (23 cm × 33 cm), was over 4 1⁄4 in (108 mm) thick, and weighed more than 13 pounds (5.9 kg). The book included a ribbon marker, head and tail bands, three-piece cloth construction, and a slipcase. An unsigned hardcover edition limited to 600 copies, was later released. Both the signed and unsigned editions are sold out.[10] A trade edition was later released.

Critical reception

In his short story collection A Century of Great Suspense Stories, editor Jeffery Deaver noted that King “singlehandedly made popular fiction grow up. While there were many good best-selling writers before him, King, more than anybody since John D. MacDonald, brought reality to genre novels. He’s often remarked that 'Salem's Lot was 'Peyton Place meets Dracula,' and so it was. The rich characterization, the careful and caring social eye, the interplay of story line and character development announced that writers could take worn themes such as vampirism and make them fresh again." [11]

Media adaptations

- Salem's Lot (1979) – television miniseries

- A Return to Salem's Lot (1987) – film and in-name only sequel to 1979 miniseries

- Salem's Lot (1995) – radio drama

- Salem's Lot (2004) – television miniseries

References

- ↑ "1976 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Archived from the original on 2009-07-25. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- ↑ "Bibliography: 'Salem's Lot". isfdb Science Fiction. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Playboy Interview: Stephen King". Playboy Philipines. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". StephenKing.com. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ↑ Phil Konstantin. "An Interview with Stephen King". Articles Written by Phil Konstantin. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ↑ Introduction to "'Salem's Lot", Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2004.

- ↑ StephenKing.com: 'Salems Lot

- ↑ "The Fright Report", Oui Magazine, January 1980, p. 108

- ↑ "The Stephen King Companion" Beahm, George Andrews McMeel press 1989, p. 267

- ↑ Official Centipede Press webpage

- ↑ A Century of Great Suspense Stories, edited by Jeffrey Deaver [Pg. 290]/Publisher: Berkley Hardcover (2001) ISBN 0425181928

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: 'Salem's Lot |

- Bookpoi - Identification characteristics for first edition copies of Salem's Lot by Stephen King.

- Salem's Lot at Worlds Without End

| |||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||