Breaker Morant (film)

| Breaker Morant | |

|---|---|

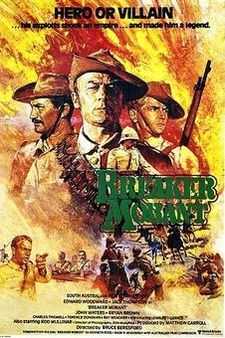

theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Bruce Beresford |

| Produced by | Matt Carroll |

| Screenplay by |

Jonathan Hardy David Stevens Bruce Beresford |

| Story by | Kenneth G. Ross |

| Starring |

Edward Woodward Jack Thompson |

| Cinematography | Donald McAlpine |

| Editing by | William M. Anderson |

| Studio | South Australian Film Corporation |

| Distributed by |

Roadshow Entertainment New World Pictures |

| Release dates |

|

| Running time | 107 minutes |

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | A$800,000[1] |

| Box office |

$4,735,000 (Australia) $3.5 million[2] |

Breaker Morant is a 1980 Australian film about the court martial of Breaker Morant, directed by Bruce Beresford and starring British actor Edward Woodward as Harry "Breaker" Morant and Jack Thompson as his attorney. The all-Australian supporting cast features Bryan Brown and Lewis Fitz-Gerald.

Beresford co-wrote the screenplay from the 1978 play Breaker Morant: A Play in Two Acts by Kenneth G. Ross.[3][4]

Breaker Morant preceded other Australian New Wave war films such as Gallipoli (1981), The Lighthorsemen (1987), and the five-part TV series ANZACS (1985). Recurring themes of these films include the Australian identity, such as mateship and larrikinism, the loss of innocence in war, and also the continued coming of age of the Australian nation and its soldiers (later called the ANZAC spirit).

The film was a top performer at the 1980 Australian Film Institute awards, with ten wins, including: Best Film, Best Direction, Leading Actor, Supporting Actor, Screenplay, Art Direction, Cinematography, and Editing. It was also nominated for the 1980 Academy Award for the Best Writing (Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium).

Plot

Three Australian Army officers of the Bushveldt Carbineers serving in South Africa during the Second Boer War (1899–1902) are on trial in a court-martial for murder. Lieutenants Harry "Breaker" Morant, Peter Handcock, and George Witton are accused of the murder of one Boer prisoner and the subsequent murders of six more. In addition, Morant and Handcock are accused of the sniper-style assassination of a German missionary, the Rev. H. C. V. Hesse. Their defence counsel, Major J. F. Thomas, has had only one day to prepare their defence.

Lord Kitchener, who ordered the trial, hopes to bring the Boer War to an end with a peace conference. To that end, he uses the Morant trial to show that he is willing to judge his own soldiers harshly if they disobey the rules of war. Although, as Major Thomas mentions in court, there are great complexities associated with charging active-duty soldiers with murder during battle, Kitchener is determined to have a guilty verdict, and the chief of the court, Lt. Colonel Denny, supports him.

Major Thomas's speech on the "barbarities of war" provides the climax of the film:

Now, when the rules and customs of war are departed from by one side, one must expect the same sort of behaviour from the other. Accordingly, officers of the Carbineers should be, and up until now have been, given the widest possible discretion in their treatment of the enemy.Now, I don't ask for proclamations condoning distasteful methods of war, but I do say that we must take for granted that it does happen. Let's not give our officers hazy, vague instructions about what they may or may not do. Let's not reprimand them, on the one hand for hampering the column with prisoners, and at another time, and another place, hold them up as murderers for obeying orders.[...]

The fact of the matter is that war changes men's natures. The barbarities of war are seldom committed by abnormal men. The tragedy of war is that these horrors are committed by normal men in abnormal situations, situations in which the ebb and flow of everyday life have departed and have been replaced by a constant round of fear, and anger, blood, and death. Soldiers at war are not to be judged by civilian rules, as the prosecution is attempting to do, even though they commit acts which, calmly viewed afterwards, could only be seen as unchristian and brutal. And if, in every war, particularly guerrilla war, all the men who committed reprisals were to be charged and tried as murderers, court martials like this one would be in permanent session. Would they not?

I say that we cannot hope to judge such matters unless we ourselves have been submitted to the same pressures, the same provocations as these men, whose actions are on trial.

The defendants are found guilty of executing the prisoners but acquitted of murdering the missionary and are sentenced to death, with Witton's sentence being commuted to "life in penal servitide."

History

After the events in this movie, Major Thomas returned to Australia and continued his civilian law practice. Witton served three years of his sentence, then was released after a national outcry. In 1907, he wrote a book entitled Scapegoats of the Empire, an account of the Breaker Morant affair (reprinted in 1982). Witton's book proved so inflammatory and anti-British that it was suppressed during both world wars.

Cast

|

|

Production

The movie was the second of two films Beresford intended to make for the South Australian Film Corporation. He wanted to make Breakout, about the Cowra Breakout, but could not find a script he was happy with so turned to the story of Breaker Morant.[1]

Funding came from the SAFC, the Australian Film Commission, the Seven Network and PACT Productions. The distributors, Roadshow, insisted that Jack Thompson be given a role.[1]

Production took place from May to June 1979. The film was shot almost entirely on location in and around the South Australian town of Burra, with the Pietersburg courtroom scenes filmed at the former Redruth Gaol. Other South Australian locations included Ayers House, Paringa Hall at Sacred Heart College, Adelaide, Rostrevor College, Woodforde and Loreto College, Marryatville.

Critical response

Rotten Tomatoes gave Breaker Morant an average rating of 8.3/10 based on 18 reviews and also comments "Superbly executed in every area, the film is a memorable evocation of the hypocrisy of empire."[5]

The film also acted to stir debate on the ongoing effect and legacy of the trial with its anti-war theme. In one analysis of the film, D. L. Kershen comments: "Breaker Morant tells the story of the court-martial of Harry Morant, Peter Handcock, and George Witton in South Africa in 1902. Yet, its overriding theme is war's evil. Breaker Morant is a beautiful anti-war statement—a plea for the end of the intrigues and crimes that war entails."[6]

Another comments: "The clear issue of the film is accountability of soldiers in war for acts condoned by their superiors. Another issue, which I find particularly fascinating, concerns the fairness of the hearing. We would ask whether due process was present, after accounting for the exigencies of the battlefield. Does Breaker Morant demonstrate what happens when due process is not observed?"[7]

Bruce Beresford claimed the film was often misunderstood as the story of men railroaded by the British:

But that's not what it's about at all. The film never pretended for a moment that they weren't guilty. It said they are guilty. But what was interesting about it was that it analysed why men in this situation would behave as they had never behaved before in their lives. It's the pressures that are put to bear on people in war time... Look at all the things that happen in these countries committed by people who appear to be quite normal. That was what I was interested in examining. I always get amazed when people say to me that this is a film about poor Australians who were framed by the Brits.[8]

After the success of Breaker Morant, Beresford was offered dozens of Hollywood scripts including Tender Mercies, which he later directed. The 1983 film earned him his only Academy Award nomination for Best Director to date, even though 1989's Driving Miss Daisy, which he directed, won Best Picture.[9] Beresford said that Breaker Morant was not that successfully commercially:

Critically, it was important, which is a key factor, and it has kept being shown over the years. Whenever I am in Los Angeles, it's always on TV. I get phone calls from people who say, 'I saw your movie, could you do something for us?' But, they're looking at a [then] twenty-year-old movie. At the time it never had an audience. Nobody went anywhere in the world. It opened and closed in America in less than a week. And in London, I remember it had four days in the West End. Commercially, a disaster, but... It's a film that people talk about to me all the time.[8]

Box office

Breaker Morant grossed $4,735,000 at the box office in Australia,[10] which is equivalent to $16,809,250 in 2009 dollars.

Awards and honours

Wins

- Australian Film Institute (1980)

- Best Achievement in Cinematography, Donald McAlpine

- Best Achievement in Costume Design, Anna Senior

- Best Achievement in Editing, William M. Anderson

- Best Achievement in Production Design, David Copping

- Best Achievement in Sound, Gary Wilkins, William Anderson, Jeanine Chiavlo, and Phil Judd.

- Best Actor in a Lead Role, Jack Thompson

- Best Actor in a Supporting Role, Bryan Brown

- Best Director, Bruce Beresford

- Best Film, Matt Carroll

- Best Original Screenplay, Jonathan Hardy, David Stevens, and Bruce Beresford

- 1980 Cannes Film Festival

- Best Supporting Actor, Jack Thompson[11]

- Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards (1982)

- Best Foreign Film

Nominations

- Academy Awards (1981)

- Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium, Jonathan Hardy, David Stevens, and Bruce Beresford

- Golden Globes (1981)

- Best Foreign Film

Release

A DVD is available by REEL Corporation (2001) with a running time of 104 minutes. Image Entertainment released a Blu-ray Disc version of the film in the US on 5 February 2008 (107 minutes), including the documentary "The Boer War", a detailed account of the historical facts depicted in the film.

See also

- Kenneth G. Ross, playwright

- Trial movies

- Court martial of Breaker Morant

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Stratton, David. The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson, 1980 p.55

- ↑ Corman, Roger & Jerome, Jim. How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime, Muller, 1990. p.191

- ↑ Subsequent to the film's release, Ross – who began writing under the name "Kenneth Ross" in order to set himself apart from other creative Australians known as "Ken Ross" – found that he must write under the name of "Kenneth G. Ross" in order to distinguish himself from that other, also famous, Kenneth Ross: the Scottish/American Kenneth Ross that was the scriptwriter for The Day of the Jackal.

- ↑ Many people labour under the misapprehension that it was Kit Denton's 1973 book The Breaker that was the source (see Ross' successful legal action for details).

- ↑ "Breaker Morant (1980)" on Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ↑ "Breaker Morant" Oklahoma City University Law Review Volume 22, Number 1 (1997). Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ↑ "Breaker Morant" on the University of Central Florida website Retrieved 24 July 2009

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Malone. Phone interview with Bruce Beresford (15 May 1999) accessed 17 October 2012

- ↑ Miracles & Mercies at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Film Victoria – Australian Films at the Australian Box Office"

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Breaker Morant". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

Bibliography

- Ross, K.G., Breaker Morant: A Play in Two Acts, Edward Arnold, (Melbourne), 1979. ISBN 0-7267-0997-2

- Ross, Kenneth (26 February 2002). "The truth about Harry". The Age. Written on the hundredth anniversary of Morant's execution and the twenty-fourth anniversary of the first performance of his play. Article was reprinted in The Sydney Morning Herald on the same date.

External links

| |||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||