Etendue

Etendue or étendue ("ay-ten-due") is a property of pencils of rays in an optical system, which characterizes how "spread out" light is in area and angle. It may also be seen as a volume in phase space.

From the source point of view, it is the area of the source times the solid angle the system's entrance pupil subtends as seen from the source. From the system point of view, the etendue is the area of the entrance pupil times the solid angle the source subtends as seen from the pupil. These definitions must be applied for infinitesimally small "elements" of area and solid angle, which must then be summed over both the source and the diaphragm as shown below.

Etendue is important because it never decreases in any optical system. A perfect optical system produces an image with the same etendue as the source. The etendue is related to the Lagrange invariant and the optical invariant, which share the property of being constant in an ideal optical system. The radiance of an optical system is equal to the derivative of the radiant flux with respect to the etendue.

The term étendue comes from the French word for extent or spread. The French word for the optical property is étendue géométrique, meaning "geometrical extent".

Other names for this property are acceptance, throughput, light-grasp, collecting power, and the AΩ product. Throughput and AΩ product are especially used in radiometry and radiative transfer where it is related to the view factor (or shape factor). It is a central concept in nonimaging optics.[1][2]

Contents |

Definition

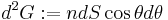

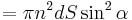

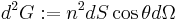

An infinitesimal surface element, dS, with normal nS is immersed in a medium of refractive index n. The surface is crossed by (or emits) light confined to a solid angle, dΩ, at an angle θ with the normal nS . The area of dS projected in the direction of the light propagation is . The etendue of this light crossing dS is defined in 2D as

. The etendue of this light crossing dS is defined in 2D as

and in 3D as

.

.

Because angles, solid angles, and refractive indices are dimensionless quantities, etendue has units of area (given by dS).

Conservation of etendue

As shown below, etendue is conserved as light travels through free space and at refractions or reflections. It is then also conserved as light travels through optical systems where it suffers perfect reflections or refractions. However, if light was to hit, say, a diffuser, its solid angle would increase, increasing the etendue. Etendue can then remain constant or it can increase as light propagates through an optic, but it cannot decrease.

Conservation of etendue can be derived in different contexts, such as from optical first principles, from Hamiltonian optics or from the second law of thermodynamics.[1]

Conservation of etendue in free space

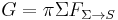

Consider a light source, Σ, and a light "receiver", S, both of which are extended surfaces (rather than differential elements), and which are separated by a medium of refractive index n that is perfectly transparent (shown). To compute the etendue of the system, one must consider the contribution of each point on the surface of the light source as they cast rays to each point on the receiver.[3]

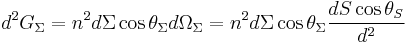

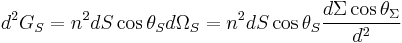

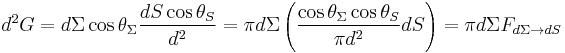

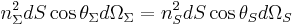

According to the definition above, the etendue of the light crossing dΣ towards dS is given by:

where  is the solid angle defined by area dS at area dΣ. Accordingly, the etendue of the light crossing dS coming from dΣ is given by:

is the solid angle defined by area dS at area dΣ. Accordingly, the etendue of the light crossing dS coming from dΣ is given by:

where  is the solid angle defined by area dΣ. These expressions result in

is the solid angle defined by area dΣ. These expressions result in  showing that etendue is conserved as light propagates in free space.

showing that etendue is conserved as light propagates in free space.

The etendue of the whole system is then:

If both surfaces dΣ and dS are immersed in air (or in vacuum), n=1 and the expression above for the etendue may be written as

where  is the view factor between differential areas dΣ and dS. Integration on dΣ and dS results in

is the view factor between differential areas dΣ and dS. Integration on dΣ and dS results in  which allows the etendue between two surfaces to be obtained from the view factors between those surfaces, as provided in a list of view factors for specific geometry cases or in several heat transfer textbooks.

which allows the etendue between two surfaces to be obtained from the view factors between those surfaces, as provided in a list of view factors for specific geometry cases or in several heat transfer textbooks.

The conservation of etendue in free space is related to the reciprocity theorem for view factors.

Conservation of etendue in refractions and reflections

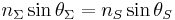

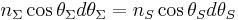

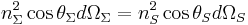

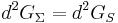

The conservation of etendue discussed above applies to the case of light propagation in free space, or more generally, in a medium in which the refractive index is constant. However, etendue is also conserved in refractions and reflections.[1] Figure "etendue in refraction" shows an infinitesimal surface dS on the xy plane separating two media of refractive indices nΣ and nS.

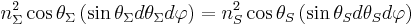

The normal to dS points in the direction of the z axis. Incoming light is confined to a solid angle dΩΣ and reaches dS at an angle θΣ to its normal. Refracted light is confined to a solid angle dΩS and leaves dS at an angle θS to its normal. The directions of the incoming and refracted light are contained in a plane making an angle φ to the z axis, defining these directions in a spherical coordinate system. With these definitions, Snell's law of refraction can be written as

and its derivative relative to θ

multiplied by each other result in

where both sides of the equation were also multiplied by dφ which does not change on refraction. This expression can now be written as

and multiplying both sides by dS we get

⇔

⇔

showing that the etendue of the light refracted at dS is conserved. The same result is also valid for the case of a reflection at a surface dS, in which case nΣ=nS and θΣ=θS.

Conservation of basic radiance

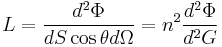

Radiance is defined by

where n is the refractive index in which dS is immersed and d2Φ is the is the radiant flux emitted by or crossing surface dS inside solid angle dΩ. As light travels through an ideal optical system, both the etendue and the energy flux are conserved. Therefore, the basic radiance defined as[4]

is also conserved. In real systems etendue may increase (for example due to diffusion) or the light flux may decrease (for example due to absorption) and, therefore, basic radiance may decrease. However, etendue may not decrease and energy flux may not increase and, therefore, basic radiance may not increase.

Etendue as a volume in phase space

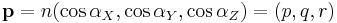

In the context of Hamiltonian optics, at a point in space, a light ray may be completely defined by a point P=(x,y,z), a unit Euclidean vector  indicating its direction and the refractive index n at point P. The optical momentum of the ray at that point is defined by

indicating its direction and the refractive index n at point P. The optical momentum of the ray at that point is defined by

with  . The geometry of the optical momentum vector is illustrated in figure "optical momentum".

. The geometry of the optical momentum vector is illustrated in figure "optical momentum".

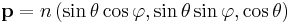

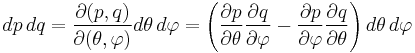

In a spherical coordinate system p may be written as

from which

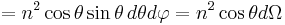

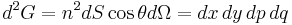

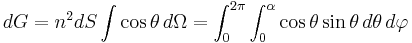

and therefore, for an infinitesimal area dS=dxdy on the xy plane immersed in a meduim of refractive index n, the etendue is given by

which is an infinitesimal volume in phase space x,y,p,q. Conservation or etendue in phase space is the equivalent in optics to Liouville's theorem in classical mechanics.[1] Etendue as volume in phase space is commonly used in nonimaging optics.

Maximum concentration

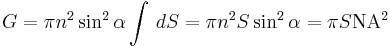

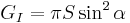

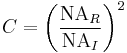

Consider an infinitesimal area, dS, immersed in a medium of refractive index n crossed by (or emitting) light inside a cone of angle α. The etendue of this light is given by

Noting that  is the numerical aperture, NA, of the beam of light, this can also be expressed as

is the numerical aperture, NA, of the beam of light, this can also be expressed as

.

.

Note that dΩ is expressed in a spherical coordinate system. Now, if a large surface S is crossed by (or emits) light also confined to a cone of angle α, the etendue of the light crossing S is

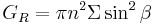

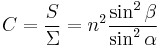

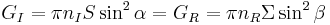

The limit on maximum concentration (shown) is an optic with an entrance aperture, S, in air (nI=1) collecting light within a solid angle of angle 2α and sending it to a smaller area receiver Σ immersed in a medium of refractive index n, whose points are illuminated within a solid angle of angle 2β. From the above expression, the etendue of the incoming light is

and the etendue of the light reaching the receiver is

Conservation of etendue GI=GR then gives

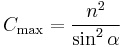

where C is the concentration of the optic. For a given angular aperture, α, of the incoming light, this concentration will be maximum for the maximum value of β, that is β=π/2. The maximum possible concentration is then[1][2]

In the case that the incident index is not unity, we have

and so

and in the best-case limit of  , this becomes

, this becomes

.

.

If the optic were a collimator instead of a concentrator, the light direction is reversed and conservation of etendue gives us the minimum aperture, S, for a given output full angle 2α.

References

- ^ a b c d e Julio Chaves, Introduction to Nonimaging Optics, CRC Press, 2008 [ISBN 978-1420054293]

- ^ a b Roland Winston et al.,, Nonimaging Optics, Academic Press, 2004 [ISBN 978-0127597515]

- ^ Wikilivre de Photographie, Notion d'étendue géométrique (in French). Accessed 27 Jan 2009.

- ^ William Ross McCluney, Introduction to Radiometry and Photometry, Artech House, Boston, MA, 1994 [ISBN 978-0890066782]

See also

Further reading

- Greivenkamp, John E. (2004). Field Guide to Geometrical Optics. SPIE Field Guides vol. FG01. SPIE. ISBN 0-8194-5294-7.

- Xutao Sun et al., 2006, "Etendue analysis and measurement of light source with elliptical reflector", Displays (27), 56–61.