Zariski topology

In algebraic geometry, the Zariski topology is a particular topology chosen for algebraic varieties that reflects the algebraic nature of their definition. It is due to Oscar Zariski and took a place of particular importance in the field around 1950. The more subtle étale topology is a refinement of the Zariski topology discovered by Grothendieck in the 1960s that reflects the geometry more accurately.

Contents |

The classical definition

In classical algebraic geometry (that is, the subject prior to the Grothendieck revolution of the late 1950s and 1960s) the Zariski topology was defined in the following way. Just as the subject itself was divided into the study of affine and projective varieties (see the Algebraic variety definitions) the Zariski topology is defined slightly differently for these two. We assume that we are working over a fixed, algebraically closed field k, which in classical geometry was almost always the complex numbers.

Affine varieties

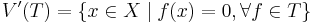

First we define the topology on affine spaces  which as sets are just n-dimensional vector spaces over k. The topology is defined by specifying its closed, rather than its open sets, and these are taken simply to be all the algebraic sets in

which as sets are just n-dimensional vector spaces over k. The topology is defined by specifying its closed, rather than its open sets, and these are taken simply to be all the algebraic sets in  That is, the closed sets are those of the form

That is, the closed sets are those of the form

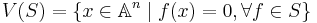

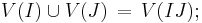

where S is any set of polynomials in n variables over k. It is a straightforward verification to show that:

- V(S) = V((S)), where (S) is the ideal generated by the elements of S;

- For any two ideals of polynomials I, J, we have

It follows that finite unions and arbitrary intersections of the sets V(S) are also of this form, so that these sets form the closed sets of a topology (equivalently, their complements, denoted D(S) and called principal open sets, form the topology itself). This is the Zariski topology on

If X is an affine algebraic set (irreducible or not) then the Zariski topology on it is defined simply to be the subspace topology induced by its inclusion into some  Equivalently, it can be checked that:

Equivalently, it can be checked that:

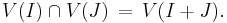

- The elements of the affine coordinate ring

act as functions on X just as the elements of ![k[x_1, \dots, x_n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0e5faffda55ea8da5ff04631b8fe59d7.png) act as functions on

act as functions on

- For any set of polynomials S, let T be the set of their images in A(X). Then the subset of X

(these notations are not standard) is equal to the intersection with X of V(S).

This establishes that the above equation, clearly a generalization of the previous one, defines the Zariski topology on any affine variety.

Projective varieties

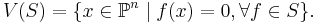

Recall that n-dimensional projective space  is defined to be the set of equivalence classes of non-zero points in

is defined to be the set of equivalence classes of non-zero points in  by identifying two points that differ by a scalar multiple in k. The elements of the polynomial ring

by identifying two points that differ by a scalar multiple in k. The elements of the polynomial ring ![k[x_0, \dots, x_n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/75b763e3e8cc6e50d129464b69cefb2b.png) are not functions on

are not functions on  because any point has many representatives that yield different values in a polynomial; however, the homogeneous polynomials do have well-defined zero or nonzero values on any projective point since the scalar multiple factors out of the polynomial. Therefore if S is any set of homogeneous polynomials we may reasonably speak of

because any point has many representatives that yield different values in a polynomial; however, the homogeneous polynomials do have well-defined zero or nonzero values on any projective point since the scalar multiple factors out of the polynomial. Therefore if S is any set of homogeneous polynomials we may reasonably speak of

The same facts as above may be established for these sets, except that the word "ideal" must be replaced by the phrase "homogeneous ideal", so that the V(S), for sets S of homogeneous polynomials, define a topology on  As above the complements of these sets are denoted D(S), or, if confusion is likely to result, D′(S).

As above the complements of these sets are denoted D(S), or, if confusion is likely to result, D′(S).

The projective Zariski topology is defined for projective algebraic sets just as the affine one is defined for affine algebraic sets, by taking the subspace topology. Similarly, it may be shown that this topology is defined intrinsically by sets of elements of the projective coordinate ring, by the same formula as above.

Properties

A very useful fact about these topologies is that we may exhibit a basis for them consisting of particularly simple elements, namely the D(f) for individual polynomials (or for projective varieties, homogeneous polynomials) f. Indeed, that these form a basis follows from the formula for the intersection of two Zariski-closed sets given above (apply it repeatedly to the principal ideals generated by the generators of (S)). These are called distinguished or basic open sets.

By the Hilbert Basis Theorem and some elementary properties of Noetherian rings, every affine or projective coordinate ring is Noetherian. As a consequence, affine or projective spaces with the Zariski topology are Noetherian topological spaces, which implies that any subset of these spaces is compact.

However, unless k is a finite field no variety is ever a Hausdorff space. In the old topological literature "compact" was taken to include the Hausdorff property, and this convention is still honored in algebraic geometry; therefore compactness in the modern sense is called "quasicompactness" in algebraic geometry. However, since every point (a1, ..., an) is the zero set of the polynomials x1 - a1, ..., xn - an, points are closed and so every variety satisfies the T1 axiom.

Every regular map of varieties is continuous in the Zariski topology. In fact, the Zariski topology is the weakest topology (with the fewest open sets) in which this is true and in which points are closed. This is easily verified by noting that the Zariski-closed sets are simply the intersections of the inverse images of 0 by the polynomial functions, considered as regular maps into

The modern definition

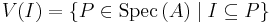

Modern algebraic geometry takes the spectrum of a ring (the set of proper prime ideals) as its starting point. In this formulation, the Zariski-closed sets are taken to be the sets

where A is a fixed commutative ring and I is an ideal. To see the connection with the classical picture, note that for any set S of polynomials (over an algebraically closed field), it follows from Hilbert's Nullstellensatz that the points of V(S) (in the old sense) are exactly the tuples (a1, ..., an) such that (x1 - a1, ..., xn - an) contains S; moreover, these are maximal ideals and by the "weak" Nullstellensatz, an ideal of any affine coordinate ring is maximal if and only if it is of this form. Thus, V(S) is "the same as" the maximal ideals containing S. Grothendieck's innovation in defining Spec was to replace maximal ideals with all prime ideals; in this formulation it is natural to simply generalize this observation to the definition of a closed set in the spectrum of a ring.

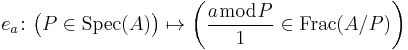

Another way, perhaps more similar to the original, to interpret the modern definition is to realize that the elements of A can actually be thought of as functions on the prime ideals of A; namely, as functions on Spec A. Simply, any prime ideal P has a corresponding residue field, which is the field of fractions of the quotient A/P, and any element of A has a reflection in this residue field. Furthermore, the elements that are actually in P are precisely those whose reflection vanishes. So if we think of the map, associated to any element a of A:

("evaluation of a"), which assigns to each point its reflection in the residue field there, as a function on Spec A (whose values, admittedly, lie in different fields at different points), then this function vanishes precisely at the points of V((a)). More generally, V(I) for any ideal I is the common set on which all the "functions" in I vanish, which is formally similar to the classical definition. In fact, they agree in the sense that when A is the ring of polynomials over some algebraically closed field k, the maximal ideals of A are (as discussed in the previous paragraph) identified with n-tuples of elements of k, their residue fields are just k, and the "evaluation" maps are actually evaluation of polynomials at the corresponding n-tuples. Since as shown above, the classical definition is essentially the modern definition with only maximal ideals considered, this shows that the interpretation of the modern definition as "zero sets of functions" agrees with the classical definition where they both make sense.

Just as Spec replaces affine varieties, the Proj construction replaces projective varieties in modern algebraic geometry. Just as in the classical case, to move from the affine to the projective definition we need only replace "ideal" by "homogeneous ideal", though there is a complication involving the "irrelevant maximal ideal," which is discussed in the cited article.

Examples

- Spec k, the spectrum of a field k is the topological space with one element.

- Spec ℤ, the spectrum of the integers has a closed point for every prime number p corresponding to the maximal ideal (p) ⊂ ℤ, and one non-closed generic point (i.e., whose closure is the whole space) corresponding to the zero ideal (0). So the closed subsets of Spec ℤ are precisely finite unions of closed points and the whole space.

- Spec k[t], the spectrum of the polynomial ring over a field k, which is also denoted

, the affine line: the polynomial ring is known to be a principal ideal domain and the irreducible polynomials are the prime elements of k[t]. If k is algebraically closed, for example the field of complex numbers, a non-constant polynomial is irreducible if and only if it is linear, of the form t − a, for some element a of k. So, the spectrum consists of one closed point for every element a of k and a generic point, corresponding to the zero ideal. If k is not algebraically closed, for example the field of real numbers, the picture becomes more complicated because of the existence of non-linear irreducible polynomials. For example, the spectrum of ℝ[t] consists of closed points (x − a), for a in ℝ, (x2 + px + q) where p, q are in ℝ and with negative discriminant p2 − 4q < 0, and finally a generic point (0). For any field, the closed subsets of Spec k[t] are finite unions of closed points, and the whole space. (This is clear from the above discussion for algebraically closed fields. The proof of the general case requires some commutative algebra, namely the fact, that the Krull dimension of k[t] is one — see Krull's principal ideal theorem).

, the affine line: the polynomial ring is known to be a principal ideal domain and the irreducible polynomials are the prime elements of k[t]. If k is algebraically closed, for example the field of complex numbers, a non-constant polynomial is irreducible if and only if it is linear, of the form t − a, for some element a of k. So, the spectrum consists of one closed point for every element a of k and a generic point, corresponding to the zero ideal. If k is not algebraically closed, for example the field of real numbers, the picture becomes more complicated because of the existence of non-linear irreducible polynomials. For example, the spectrum of ℝ[t] consists of closed points (x − a), for a in ℝ, (x2 + px + q) where p, q are in ℝ and with negative discriminant p2 − 4q < 0, and finally a generic point (0). For any field, the closed subsets of Spec k[t] are finite unions of closed points, and the whole space. (This is clear from the above discussion for algebraically closed fields. The proof of the general case requires some commutative algebra, namely the fact, that the Krull dimension of k[t] is one — see Krull's principal ideal theorem).

Properties

The most dramatic change in the topology from the classical picture to the new is that points are no longer necessarily closed; by expanding the definition, Grothendieck introduced generic points whose closures are strictly larger than themselves. The closed points correspond to maximal ideals of A. Note, however, that the spectrum and projective spectrum are still T0 spaces: given two points P, Q, which are prime ideals of A, at least one of them does not contain the other, say P. Then D(Q) contains P but, of course, not Q.

Just as in classical algebraic geometry, any spectrum or projective spectrum is compact, and if the ring in question is Noetherian then the space is a Noetherian space. However, these facts are counterintuitive: we do not normally expect open sets, other than connected components, to be compact, and for affine varieties (for example, Euclidean space) we do not even expect the space itself to be compact. This is one instance of the geometric unsuitability of the Zariski topology. Grothendieck solved this problem by defining the notion of properness of a scheme (actually, of a morphism of schemes), which recovers the intuitive idea of compactness: Proj is proper, but Spec is not.

See also

References

- Hartshorne, Robin (1977), Algebraic Geometry, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90244-9, OCLC 13348052, MR0463157

- Todd Rowland, "Zariski Topology" from MathWorld.

![A(X)\,=\,k[x_1, \dots, x_n]/I(X)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/29b0ec3512820a2bbef23ac589f092ca.png)