YUV

YUV is a color space typically used as part of a color image pipeline. It encodes a color image or video taking human perception into account, allowing reduced bandwidth for chrominance components, thereby typically enabling transmission errors or compression artifacts to be more efficiently masked by the human perception than using a "direct" RGB-representation. Other color spaces have similar properties, and the main reason to implement or investigate properties of Y'UV would be for interfacing with analog or digital television or photographic equipment that conforms to certain Y'UV standards.

The scope of the terms Y'UV, YUV, YCbCr, YPbPr, etc., is sometimes ambiguous and overlapping. Historically, the terms YUV and Y'UV were used for a specific analog encoding of color information in television systems, while YCbCr was used for digital encoding of color information suited for video and still-image compression and transmission such as MPEG and JPEG. Today, the term YUV is commonly used in the computer industry to describe file-formats that are encoded using YCbCr.

The Y'UV model defines a color space in terms of one luma (Y') and two chrominance (UV) components. The Y'UV color model is used in the PAL and SECAM composite color video standards. Previous black-and-white systems used only luma (Y') information. Color information (U and V) was added separately via a sub-carrier so that a black-and-white receiver would still be able to receive and display a color picture transmission in the receiver's native black-and-white format.

Y' stands for the luma component (the brightness) and U and V are the chrominance (color) components; luminance is denoted by Y and luma by Y' – the prime symbols (') denote gamma compression,[1] with "luminance" meaning perceptual (color science) brightness, while "luma" is electronic (voltage of display) brightness.

The YPbPr color model used in analog component video and its digital version YCbCr used in digital video are more or less derived from it, and are sometimes called Y'UV. (CB/PB and CR/PR are deviations from grey on blue–yellow and red–cyan axes, whereas U and V are blue–luminance and red–luminance differences.) The Y'IQ color space used in the analog NTSC television broadcasting system is related to it, although in a more complex way.

Contents |

History

Y'UV was invented when engineers wanted color television in a black-and-white infrastructure.[2] They needed a signal transmission method that was compatible with black-and-white (B&W) TV while being able to add color. The luma component already existed as the black and white signal; they added the UV signal to this as a solution.

The UV representation of chrominance was chosen over straight R and B signals because U and V are color difference signals. This meant that in a black and white scene the U and V signals would be zero and only the Y' signal would need to be transmitted. If R and B were to have been used, these would have non-zero values even in a B&W scene, requiring all three data-carrying signals. This was important in the early days of color television, because holding the U and V signals to zero while connecting the black and white signal to Y' allowed color TV sets to display B&W TV without the additional expense and complexity of special B&W circuitry. In addition, black and white receivers could take the Y' signal and ignore the color signals, making Y'UV backward-compatible with all existing black-and-white equipment, input and output. It was necessary to assign a narrower bandwidth to the chrominance channel because there was no additional bandwidth available. If some of the luminance information arrived via the chrominance channel (as it would have if RB signals were used instead of differential UV signals), B&W resolution would have been compromised.[3]

Conversion to/from RGB

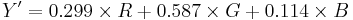

Y'UV signals are typically created from RGB (red, green and blue) source. Weighted values of R, G, and B are summed to produce Y', a measure of overall brightness or luminance. U and V are computed as scaled differences between Y' and the B and R values.

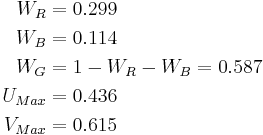

Defining the following constants:

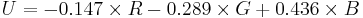

Y'UV is computed from RGB as follows:

The resulting ranges of Y', U, and V respectively are [0, 1], [-UMax, UMax], and [-VMax, VMax].

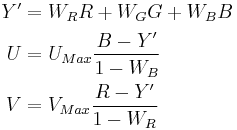

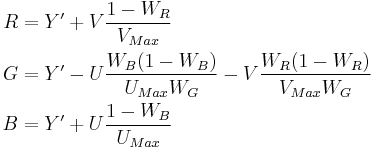

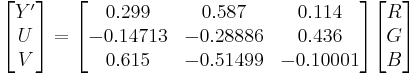

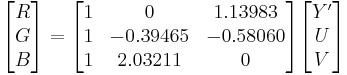

Inverting the above transformation converts Y'UV to RGB:

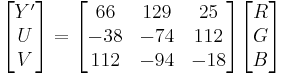

Equivalently, substituting values for the constants and expressing them as matrices gives:

Notes

The weights used to compute Y' (top row of matrix) are identical to those used in the Y'IQ color space.

Equal values of red, green and blue (i.e. levels of gray) yield 0 for U and V. Black, RGB=(0, 0, 0), yields YUV=(0, 0, 0). White, RGB=(1, 1, 1), yields YUV=(1, 0, 0).

These formulas are traditionally used in analog televisions and equipment; digital equipment such as HDTV and digital video cameras use Y'CbCr.

BT.709 and BT.601

When standardising high-definition video, the ATSC chose a different formula for the YCbCr than that used for standard-definition video. This means that when converting between SDTV and HDTV, the color information has to be altered, in addition to image scaling the video.

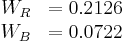

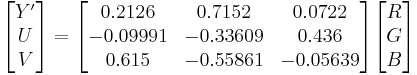

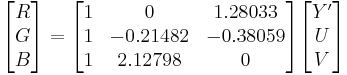

The formulae above reference Rec. 601. For HDTV, a slightly different matrix is used, where WR and WB in the above formula is replaced by Rec. 709:

This gives the matrices :

Numerical approximations

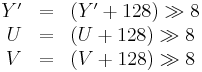

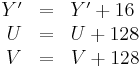

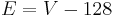

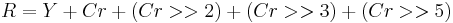

Prior to the development of fast SIMD floating-point processors, most digital implementations of RGB->Y'UV used integer math, in particular fixed-point approximations. In the following examples, the operator " " denotes a right-shift of a by b bits.

" denotes a right-shift of a by b bits.

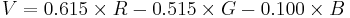

Traditional 8 bit representation of Y'UV with unsigned integers uses the following

1. Basic transform

2. Scale down to 8 bits with rounding

3. Shift values

Y' values are conventionally shifted and scaled to the range [16, 235] (referred to as studio swing) rather than using the full range of [0, 255] (referred to as full swing). This confusing practice derives from the MPEG standards and explains why 16 is added to Y' and why the Y' coefficients in the basic transform sum to 220 instead of 255. U and V values, which may be positive or negative, are summed with 128 to make them always positive.[4]

Luminance/chrominance systems in general

The primary advantages of luma/chroma systems such as Y'UV, and its relatives Y'IQ and YDbDr, are that they remain compatible with black and white analog television (largely due to the work of Georges Valensi). The Y' channel saves nearly all the data recorded by black and white cameras, so it produces a signal suitable for reception on old monochrome displays. In this case, the U and V are simply discarded. If displaying color, all three channels are used, and the original RGB information can be decoded.

Another advantage of Y'UV is that some of the information can be discarded in order to reduce bandwidth. The human eye has fairly little spatial sensitivity to color: the accuracy of the brightness information of the luminance channel has far more impact on the image detail discerned than that of the other two. Understanding this human shortcoming, standards such as NTSC reduce the bandwidth of the chrominance channels considerably. (Bandwidth is in the temporal domain, but this translates into the spatial domain as the image is scanned out.)

Therefore, the resulting U and V signals can be substantially "compressed". In the NTSC (Y'IQ) and PAL systems, the chrominance signals had significantly narrower bandwidth than that for the luminance. Early versions of NTSC rapidly alternated between particular colors in identical image areas to make them appear adding up to each other to the human eye, while all modern analogue and even most digital video standards use chroma subsampling by recording a picture's color information at only half the resolution compared to the brightness information. This ratio is the most common form, known as 4:2:2, which is the sample ratio of Y:U:V, or Y:I:Q. The 4:x:x standard was adopted due to the very earliest color NTSC standard which used a chroma subsampling of 4:1:1 so that the picture carried only a quarter as much resolution in color than it did in brightness. Today, only high-end equipment processing uncompressed signals uses a chroma subsampling of 4:4:4 with identical resolution for both brightness and color information.

The I and Q axes were chosen according to bandwidth needed by human vision, one axis being that requiring the most bandwidth, and the other (fortuitously at 90 degrees) the minimum. However, true I and Q demodulation was relatively more complex, requiring two analog delay lines, and NTSC receivers rarely used it.

However, this color space conversion is lossy, particularly obvious in crosstalk from the luma to the chroma-carrying wire, and vice versa, in analogue equipment (including RCA connectors to transfer a digital signal, as all they carry is analogue composite video, which is either YUV, YIQ, or even CVBS). Furthermore, NTSC and PAL encoded color signals in a manner that causes high bandwidth chroma and luma signals to mix with each other in a bid to maintain backward compatibility with black and white television equipment, which results in dot crawl and cross color artifacts. When the NTSC standard was created in the 1950s, this was not a real concern since the quality of the image was limited by the monitor equipment, not the limited-bandwidth signal being received. However today's modern television is capable of displaying more information than is contained in these lossy signals. To keep pace with the abilities of new display technologies, attempts were made since the late 1970s to preserve more of the Y'UV signal while transferring images, such as SCART (1977) and S-Video (1987) connectors.

Instead of Y'UV, Y'CbCr was used as the standard format for (digital) common video compression algorithms such as MPEG-2. Digital television and DVDs preserve their compressed video streams in the MPEG-2 format, which uses a full Y'CbCr color space, although retaining the established process of chroma subsampling. The professional CCIR 601 digital video format also uses Y'CbCr at the common chroma subsampling rate of 4:2:2, primarily for compatibility with previous analog video standards. This stream can be easily mixed into any output format needed.

Y'UV is not an absolute color space. It is a way of encoding RGB information, and the actual color displayed depends on the actual RGB colorants used to display the signal. Therefore a value expressed as Y'UV is only predictable if standard RGB colorants are used (i.e. a fixed set of primary chromaticities, or particular set of red, green, and blue).

Confusion with Y'CbCr

Y'UV is often used as the term for YCbCr. However, they are different formats. Y'UV is an analog system with scale factors different from the digital Y'CbCr system.[5]

In digital video/image systems, Y'CbCr is the most common way to express color in a way suitable for compression/transmission. The confusion stems from computer implementations and text-books erroneously using the term YUV where Y'CbCr would be correct.

Types of sampling

To get a digital signal, Y'UV images can be sampled in several different ways; see chroma subsampling.

Converting between Y'UV and RGB

The function [R, G, B] = Y'UV444toRGB888(Y', U, V) converts Y'UV format to simple RGB format and could be implemented using floating point arithmetic as:

Y'UV444

The RGB conversion formulae used for Y'UV444 format are also applicable to the standard NTSC TV transmission format of YUV420 (or YUV422 for that matter). For YUV420, since each U or V sample is used to represent 4 Y samples that form a square, a proper sampling method can allow the utilization of the exact conversion formulae shown below. For more details, please see the 420 format demonstration in the bottom section of this article.

These formulae are based on the NTSC standard;

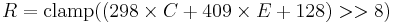

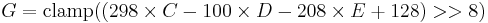

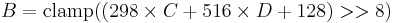

On older, non-SIMD architectures, floating point arithmetic is much slower than using fixed-point arithmetic, so an alternative formulation is:

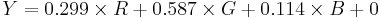

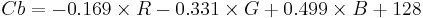

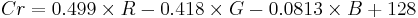

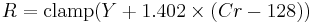

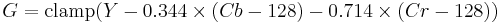

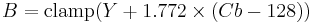

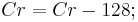

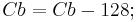

Using the previous coefficients and noting that clamp() denotes clamping a value to the range of 0 to 255, the following formulae provide the conversion from Y'UV to RGB (NTSC version):

Note: The above formulae are actually implied for YCbCr. Though the term YUV is used here, it should be noted that YUV and YCbCr are not exactly the same in a strict manner.

The ITU-R version of the formulae is different:

Integer operation of ITU-R standard for YCbCr(8 bits per channel) to RGB888:

Y'UV422

- Input: Read 4 bytes of Y'UV (u, y1, v, y2 )

- Output: Writes 6 bytes of RGB (R, G, B, R, G, B)

y1 = yuv[0]; u = yuv[1]; y2 = yuv[2]; v = yuv[3];

Using this information it could be parsed as regular Y'UV444 format to get 2 RGB pixels info:

rgb1 = Y'UV444toRGB888(y1, u, v); rgb2 = Y'UV444toRGB888(y2, u, v);

Y'UV422 can also be expressed in YUY2 FourCC format code. That means 2 pixels will be defined in each macropixel (four bytes) treated in the image. .

Y'UV411

// Extract YUV components u = yuv[0]; y1 = yuv[1]; y2 = yuv[2]; v = yuv[3]; y3 = yuv[4]; y4 = yuv[5];

rgb1 = Y'UV444toRGB888(y1, u, v); rgb2 = Y'UV444toRGB888(y2, u, v); rgb3 = Y'UV444toRGB888(y3, u, v); rgb4 = Y'UV444toRGB888(y4, u, v);

So the result is we are getting 4 RGB pixels values (4*3 bytes) from 6 bytes. This means reducing the size of transferred data to half, with a loss of quality.

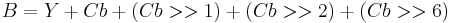

Y'UV420p (and Y'V12 or YV12)

Y'UV420p is a planar format, meaning that the Y', U, and V values are grouped together instead of interspersed. The reason for this is that by grouping the U and V values together, the image becomes much more compressible. When given an array of an image in the Y'UV420p format, all the Y' values come first, followed by all the U values, followed finally by all the V values.

The Y'V12 format is essentially the same as Y'UV420p, but it has the U and V data reversed: the Y' values are followed by the V values, with the U values last. As long as care is taken to extract U and V values from the proper locations, both Y'UV420p and Y'V12 can be processed using the same algorithm.

As with most Y'UV formats, there are as many Y' values as there are pixels. Where X equals the height multiplied by the width, the first X indices in the array are Y' values that correspond to each individual pixel. However, there are only one fourth as many U and V values. The U and V values correspond to each 2 by 2 block of the image, meaning each U and V entry applies to four pixels. After the Y' values, the next X/4 indices are the U values for each 2 by 2 block, and the next X/4 indices after that are the V values that also apply to each 2 by 2 block.

Translating Y'UV420p to RGB is a more involved process compared to the previous formats. Lookup of the Y', U and V values can be done using the following method:

size.total = size.width * size.height; y = yuv[position.y * size.width + position.x]; u = yuv[(position.y / 2) * (size.width / 2) + (position.x / 2) + size.total]; v = yuv[(position.y / 2) * (size.width / 2) + (position.x / 2) + size.total + (size.total / 4)]; rgb = Y'UV444toRGB888(y, u, v);

Here "/" is Div not division.

As shown in the above image, the Y', U and V components in Y'UV420 are encoded separately in sequential blocks. A Y' value is stored for every pixel, followed by a U value for each 2×2 square block of pixels, and finally a V value for each 2×2 block. Corresponding Y', U and V values are shown using the same color in the diagram above. Read line-by-line as a byte stream from a device, the Y' block would be found at position 0, the U block at position x×y (6×4 = 24 in this example) and the V block at position x×y + (x×y)/4 (here, 6×4 + (6×4)/4 = 30).

References

- ^ Engineering Guideline EG 28, "Annotated Glossary of Essential Terms for Electronic Production," SMPTE, 1993.

- ^ Maller, Joe. RGB and YUV Color, FXScript Reference

- ^ W. Wharton & D. Howorth, Principles of Television Reception, Pitman Publishing, 1971, pp 161-163

- ^ Keith Jack. Video Demystified. ISBN 1-878707-09-4.

- ^ Poynton, Charles (1999-06-19). YUV and luminance considered harmful. http://www.poynton.com/papers/YUV_and_luminance_harmful.html. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

External links

- RGB/Y'UV Pixel Conversion

- Explanation of many different formats in the Y'UV family

- Poynton, Charles. Video engineering

- Kohn, Mike. Y'UV422 to RGB using SSE/Assembly

- YUV, YCbCr, YPbPr colour spaces.

- Color formats for image and video processing - Color conversion between RGB, YUV, YCbCr and YPbPr.

- How to convert RGB to YUV420P

- C library of SSE-optimised color format conversions.

|

||||||||||||||||||||