Wet-bulb temperature

The wet-bulb temperature is a type of temperature measurement that reflects the physical properties of a system with a mixture of a gas and a vapor, usually air and water vapor. Wet bulb temperature is the lowest temperature that can be reached by the evaporation of water only. It is the temperature one feels when one's skin is wet and is exposed to moving air. Unlike dry bulb temperature, wet bulb temperature is an indication of the amount of moisture in the air. Wet-bulb temperature can have several technical meanings:

- Thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature: the temperature a volume of air would have if cooled adiabatically to saturation at constant pressure by evaporation of water into it, all latent heat being supplied by the volume of air.

- The temperature read from a wet bulb thermometer

- Adiabatic wet-bulb temperature: the temperature a volume of air would have if cooled adiabatically to saturation and then compressed adiabatically to the original pressure in a moist-adiabatic process (AMS Glossary).

Contents |

Practical considerations

The thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature is the minimum temperature which may be achieved by purely evaporative cooling of a water-wetted (or even ice-covered), ventilated surface.

For a given parcel air at a known pressure and dry-bulb temperature, the thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature corresponds to unique values of relative humidity, dew point temperature, and other properties. The relationships between these values are illustrated in a psychrometric chart.

For "dry" air, air that is less than saturated (i. e. air with less than 100 percent relative humidity), the wet-bulb temperature is lower than the dry-bulb temperature due to evaporative cooling. The greater the difference between the wet and dry bulb temperatures, the drier the air and lower the relative humidity. The dew point temperature is the temperature at which the ambient air must cool to reach 100% relative humidity where condensate and rain form; and conversely, the wet bulb temperature rises to converge on the dry bulb temperature.

Cooling of the human body through perspiration is inhibited as the wet-bulb temperature (and relative humidity) of the surrounding air increases in summer. Other mechanisms may be at work in winter if there is validity to the notion of a "humid" or "damp cold."

Lower wet-bulb temperatures that correspond with drier air in summer can translate to energy savings in air-conditioned buildings due to:

- Reduced dehumidification load for ventilation air

- Increased efficiency of cooling towers

Thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature (adiabatic saturation temperature)

The thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature is the temperature a volume of air would have if cooled adiabatically to saturation by evaporation of water into it, all latent heat being supplied by the volume of air.

The temperature of an air sample that has passed over a large surface of liquid water in an insulated channel is the thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature—it has become saturated by passing through a constant-pressure, ideal, adiabatic saturation chamber.

Meteorologists and others may use the term "isobaric wet-bulb temperature" to refer to the "thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature". It is also called the "adiabatic saturation temperature".

It is the thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature that is plotted on a psychrometric chart.

The thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature is a thermodynamic property of a mixture of air and water vapor. The value indicated by a simple wet-bulb thermometer often provides an adequate approximation of the thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature.

For an accurate wet-bulb thermometer, "the wet-bulb temperature and the adiabatic saturation temperature are approximately equal for air-water vapor mixtures at atmospheric temperature and pressure. This is not necessarily true at temperatures and pressures that deviate significantly from ordinary atmospheric conditions, or for other gas–vapor mixtures."[1]

Temperature reading of wet-bulb thermometer

Wet-bulb temperature is measured using a thermometer that has its bulb wrapped in cloth—called a sock—that is kept wet with water via wicking action. Such an instrument is called a wet-bulb thermometer.

An actual wet-bulb thermometer reads a slightly different temperature than the thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature, but they are very close in value. This is due to a coincidence: for a water-air system the psychrometric ratio happens to be ~1,although for systems other than air and water they might not be close.

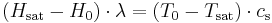

To understand why this is, first consider the calculation of the thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature: in this case, a stream of air with less than 100% relative humidity is cooled. The heat from cooling that air is used to evaporate some water which increases the humidity of the air. At some point the air reaches 100% saturation (and has cooled to the thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature). In this case we can write the following:

where  is the initial water content of the air on a mass basis,

is the initial water content of the air on a mass basis,  is the saturated water content of the air,

is the saturated water content of the air,  is the latent heat of water,

is the latent heat of water,  is the initial air temperature,

is the initial air temperature,  is the saturated air temperature and

is the saturated air temperature and  is the heat capacity of the air.

is the heat capacity of the air.

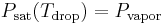

For the case of the wet-bulb thermometer, imagine a drop of water with air of less than 100% relative humidity blowing over it. As long as the vapor pressure of water in the drop is more than the partial pressure of water in the air stream, evaporation will take place. Initially the heat required for the evaporation will come from the drop itself since the fastest moving water molecules are most likely to escape the surface of drop, so the remaining water molecules will have a lower average speed and therefore a lower temperature. If this were the only thing that happened, then the drop would cool until the following was true:

where  is the saturation pressure of the water in the drop and is a function of the drop temperature and

is the saturation pressure of the water in the drop and is a function of the drop temperature and  is the partial pressure of water in the vapor phase. If the air started bone dry and was blowing sufficiently fast then

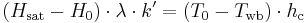

is the partial pressure of water in the vapor phase. If the air started bone dry and was blowing sufficiently fast then  would be 0 and the drop could get infinitely cold. Clearly this doesn't happen. It turns out that as the drop cools, convective heat transfer begins to occur between the warmer air and the colder water. In addition, the evaporation does not occur instantly, but instead depends on the rate of convective mass transfer between the water and the air. At a certain point the water cools to a point where the heat carried away in evaporation is equal to the heat gain through convective heat transfer. At this point the following is true:

would be 0 and the drop could get infinitely cold. Clearly this doesn't happen. It turns out that as the drop cools, convective heat transfer begins to occur between the warmer air and the colder water. In addition, the evaporation does not occur instantly, but instead depends on the rate of convective mass transfer between the water and the air. At a certain point the water cools to a point where the heat carried away in evaporation is equal to the heat gain through convective heat transfer. At this point the following is true:

where  is now the driving force for mass transfer, k' is the mass transfer coefficient (with English units of lb/(h⋅ft2)),

is now the driving force for mass transfer, k' is the mass transfer coefficient (with English units of lb/(h⋅ft2)),  is the heat transfer coefficient and

is the heat transfer coefficient and  is the temperature driving force.

is the temperature driving force.

Now if this equation is compared to the thermodynamic wet-bulb equation, we can see that if the quantity  (known as the psychrometric ratio) then

(known as the psychrometric ratio) then

Due to a coincidence, for air this is the case and the ratio is very close to 1.[2]

Experimentally, the wet-bulb thermometer reads closest to the thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature if:

- The sock is shielded from radiant heat exchange with its surroundings

- Air flows past the sock quickly enough to prevent evaporated moisture from affecting evaporation from the sock

- The water supplied to the sock is at the same temperature as the thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature of the air

In practice the value reported by a wet-bulb thermometer differs slightly from the thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature because:

- The sock is not perfectly shielded from radiant heat exchange

- Air flow rate past the sock may be less than optimum

- The temperature of the water supplied to the sock is not controlled

At relative humidities below 100 percent, water evaporates from the bulb which cools the bulb below ambient temperature. To determine relative humidity, ambient temperature is measured using an ordinary thermometer, better known in this context as a dry-bulb thermometer. At any given ambient temperature, less relative humidity results in a greater difference between the dry-bulb and wet-bulb temperatures; the wet bulb is colder. The precise relative humidity is determined by reading from a psychrometric chart of wet-bulb versus dry-bulb temperatures, or by calculation.

Psychrometers are instruments with both a wet-bulb and a dry-bulb thermometer.

A wet-bulb thermometer can also be used in combination with a globe thermometer (which is affected by the radiant temperature of the surroundings) in the calculation of the wet bulb globe temperature.

Adiabatic wet-bulb temperature

The adiabatic wet-bulb temperature is the temperature a volume of air would have if cooled adiabatically to saturation and then compressed adiabatically to the original pressure in a moist-adiabatic process (AMS Glossary). Such cooling may occur as air pressure reduces with altitude, as noted in the article on lifted condensation level.

This term, as defined in this article, may be most prevalent in meteorology.

As the value referred to as "thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature" is also achieved via an adiabatic process, some engineers and others may use the term "adiabatic wet-bulb temperature" to refer to the "thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature". As stated in another section, meteorologists and others may use the term "isobaric wet-bulb temperature" to refer to the "thermodynamic wet-bulb temperature".

"The relationship between the isobaric and adiabatic processes is quite obscure. Comparisons indicate, however, that the two temperatures are rarely different by more than a few tenths of a degree Celsius, and the adiabatic version is always the smaller of the two for unsaturated air. Since the difference is so small, it is usually neglected in practice."[3]

Wet-bulb depression

The wet-bulb depression is the difference between the dry-bulb temperature and the wet-bulb temperature. If there is 100% humidity, dry bulb and wet bulb temperatures are identical, making the wet bulb depression equal to zero in such conditions.[4]

Wet-bulb temperature and Human Health

Because excessive wet bulb temperatures can impede evaporative cooling necessary to prevent hyperthermia - a potentially fatal condition - many agencies use the measurement, together with other factors, to calculate wet bulb globe temperature, which in turn serves as the basis for heat stress prevention guidelines.

See also

References

- ^ VanWylen, Gordon J; Richard E. Sonntag (1973). Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics. John Wiley and Sons. p. 448.

- ^ http://www.probec.org/fileuploads/fl120336971099294500CHAP12_Dryers.pdf, accessed 20080408

- ^ NWSTC Remote Training Module; SKEW T LOG P DIAGRAM AND SOUNDING ANALYSIS; RTM - 230; National Weather Service Training Center; Kansas City, MO 64153; July 31, 2000

- ^ http://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/dry-wet-bulb-dew-point-air-d_682.html

External links

- Wet-bulb chart for snow making (Fahrenheit)

- Indirect evaporative cooler cools below wet-bulb

- On-line calculator returns wet-bulb temperature for given dry bulb and relative humidity

- Shortcut to calculating wet-bulb

|

|||||||||||||||||