Water hammer

Water hammer (or, more generally, fluid hammer) is a pressure surge or wave resulting when a fluid (usually a liquid but sometimes also a gas) in motion is forced to stop or change direction suddenly (momentum change). Water hammer commonly occurs when a valve is closed suddenly at an end of a pipeline system, and a pressure wave propagates in the pipe. It may also be known as hydraulic shock.

This pressure wave can cause major problems, from noise and vibration to pipe collapse. It is possible to reduce the effects of the water hammer pulses with accumulators and other features.

Rough calculations can be made either using the Joukowsky equation,[1] or more accurate ones using the method of characteristics.

Contents |

Cause and effect

If the pipe is suddenly closed at the outlet (downstream), the mass of water before the closure is still moving forward with some velocity, building up a high pressure and shock waves. In domestic plumbing this is experienced as a loud banging resembling a hammering noise. Water hammer can cause pipelines to break if the pressure is high enough. Air traps or stand pipes (open at the top) are sometimes added as dampers to water systems to provide a cushion to absorb the force of moving water in order to prevent damage to the system. (At some hydroelectric generating stations what appears to be a water tower is actually one of these devices, known as a surge drum).

In the home, water hammer may occur when a dishwasher, washing machine, or toilet shuts off water flow. The result may be heard as a loud bang, repetitive banging (as the shock wave travels back and forth in the plumbing system), or as some shuddering.

On the other hand, when an upstream valve in a pipe is closed, the water downstream of the valve will attempt to continue flowing, creating a vacuum that may cause the pipe to collapse or implode. This problem can be particularly acute if the pipe is on a downhill slope. To prevent this, air and vacuum relief valves, or air vents, are installed just downstream of the valve to allow air to enter the line and prevent this vacuum from occurring.

Other causes of water hammer are pump failure, and check valve slam (due to sudden deceleration, a check valve may slam shut rapidly, depending on the dynamic characteristic of the check valve and the mass of the water between a check valve and tank).

Related phenomena

Steam distribution systems may also be vulnerable to a situation similar to water hammer, known as steam hammer. In a steam system, water hammer most often occurs when some of the steam condenses into water in a horizontal section of the steam piping. Subsequently, steam picks up the water, forms a "slug" and hurls it at high velocity into a pipe fitting, creating a loud hammering noise and greatly stressing the pipe. This condition is usually caused by a poor condensate drainage strategy.

Where air filled traps are used, these eventually become depleted of their trapped air over a long period of time through absorption into the water. This can be cured by shutting off the supply, opening taps at the highest and lowest locations to drain the system (thereby restoring air to the traps), and then closing the taps and re-opening the supply.

Water hammer during an explosion

When an explosion happens in an enclosed space, water hammer can cause the walls of the container to deform. However, it can also impart momentum to the enclosure if it is free to move. An underwater explosion in the SL-1 reactor vessel caused the water to accelerate upwards through 2.5 feet (0.76 m) of air before it struck the vessel head at 160 feet per second (49 m/s) with a pressure of 10,000 pounds per square inch (69,000 kPa). This pressure wave caused the 26,000 pounds (12,000 kg) steel vessel to jump 9 feet 1 inch (2.77 m) into the air before it dropped into its prior location.[2]

Mitigating measures

Water hammer has caused accidents and fatalities, but usually damage is limited to breakage of pipes or appendages. An engineer should always assess the risk of a pipeline burst. Pipelines transporting hazardous liquids or gases warrant special care in design, construction, and operation.

The following characteristics may reduce or eliminate water hammer:

- Reduce the pressure of the water supply to the building by fitting a regulator.

- Lower fluid velocities. To keep water hammer low, pipe-sizing charts for some applications recommend flow velocity at or below 5 ft/s (1.5 m/s).

- Fit slowly-closing valves. Toilet flush valves are available in a quiet flush type that closes quietly.

- High pipeline pressure rating (expensive).

- Good pipeline control (start-up and shut-down procedures).

- Water towers (used in many drinking water systems) help maintain steady flow rates and trap large pressure fluctuations.

- Air vessels work in much the same way as water towers, but are pressurized. They typically have an air cushion above the fluid level in the vessel, which may be regulated or separated by a bladder. Sizes of air vessels may be up to hundreds of cubic meters on large pipelines. They come in many shapes, sizes and configurations. Such vessels often are called accumulators or expansion tanks.

- A hydropneumatic device similar in principle to a shock absorber called a 'Water Hammer Arrestor' can be installed between the water pipe and the machine which will absorb the shock and stop the banging.

- Air valves are often used to remediate low pressures at high points in the pipeline. Though effective, sometimes large numbers of air valves need be installed. These valves also allow air into the system, which is often unwanted.

- Shorter branch pipe lengths.

- Shorter lengths of straight pipe, i.e. add elbows, expansion loops. Water hammer is related to the speed of sound in the fluid, and elbows reduce the influences of pressure waves.

- Arranging the larger piping in loops that supply shorter smaller run-out pipe branches. With looped piping, lower velocity flows from both sides of a loop can serve a branch.

- Flywheel on pump.

- Pumping station bypass.

- Hydroelectric power plants must be carefully designed and maintained because the water hammer can cause water pipes to fail catastrophically.

The magnitude of the pulse

One of the first to successfully investigate the water hammer problem was the Italian engineer Lorenzo Allievi.

Water hammer can be analyzed by two different approaches, rigid column theory which ignores compressibility of the fluid and elasticity of the walls of the pipe, or by a full analysis including elasticity. When the time it takes a valve to close is long compared to the propagation time for a pressure wave to travel the length of the pipe, then rigid column theory is appropriate; otherwise considering elasticity may be necessary.[3] Below are two approximations for the peak pressure, one that considers elasticity, but assumes the valve closes instantaneously, and a second that neglects elasticity but includes a finite time for the valve to close.

Instant valve closure; compressible fluid

The pressure profile of the water hammer pulse can be calculated from the Joukowsky equation [4]

So for a valve closing instaneously, the maximum magnitude of the water hammer pulse is:

where  is the magnitude of the pressure wave (Pa),

is the magnitude of the pressure wave (Pa),  is the density of the fluid (kgm−3),

is the density of the fluid (kgm−3),  is the speed of sound in the fluid (ms−1), and

is the speed of sound in the fluid (ms−1), and  is the change in the fluid's velocity (ms−1). The pulse comes about due to Newton's laws of motion and the continuity equation applied to the deceleration of a fluid element.[5]

is the change in the fluid's velocity (ms−1). The pulse comes about due to Newton's laws of motion and the continuity equation applied to the deceleration of a fluid element.[5]

Equation for wave speed

As the speed of sound in a fluid is the  , the peak pressure will depend on the fluid compressibility if the valve is closed abruptly.

, the peak pressure will depend on the fluid compressibility if the valve is closed abruptly.

![a = \sqrt{\frac{K/\rho} {(1%2BV/a)[1%2B(K/E)(D/t)c]}}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/89a6a0f06e410dc1fe43cea036c871e3.png)

,

where

- a = wave speed

- K = bulk modulus of elasticity of the fluid

= density of the fluid

= density of the fluid- E = elastic modulus of the pipe

- D = internal pipe diameter

- t = pipe wall thickness

- c = dimensionless parameter due to system pipe-constraint condition on wave speed[5]

Slow valve closure; incompressible fluid

When the valve is closed slowly compared to the transit time for a pressure wave to travel the length of the pipe, the elasticity can be neglected, and the phenomenon can be described in terms of inertance or rigid column theory. For this case, one approximation to the maximum pressure (using Imperial units),  , produced in a water filled line is:

, produced in a water filled line is:

where  is the inlet pressure in psi,

is the inlet pressure in psi,  is the flow velocity in ft/sec,

is the flow velocity in ft/sec,  is the valve closing time in seconds and

is the valve closing time in seconds and  is the upstream pipe length in feet. [6]

is the upstream pipe length in feet. [6]

Expression for the excess pressure due to water hammer

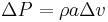

When a valve with a volumetric flow rate Q is closed, an excess pressure δP is created upstream of the valve, whose value is given by the Joukowsky equation:

In this expression[7]:

- overpressurization δP is expressed in Pa;

- Q is the volumetric flow in m3/s;

- Zh is the hydraulic impedance, expressed in kg/m4/s.

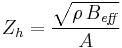

The hydraulic impedance Zh of the pipeline determines the magnitude of the water hammer pulse. It is itself defined by:

with:

- ρ the density of the liquid, expressed in kg/m3;

- A cross sectional area of the pipe, m2;

- Beff effective modulus of compressibility of the liquid in the pipe, expressed in Pa.

The latter follows from a series of hydraulic concepts:

- compressibility of the liquid, defined by its adiabatic compressibility modulus Bl, resulting from the equation of state of the liquid generally available from thermodynamic tables;

- the elasticity of the walls of the pipe, which defines a modulus of equivalent compressibility Beq. In the case of a pipe of circular cross section whose thickness e is small compared to the diameter D, the equivalent modulus of compressibility is given by the following formula:

; in which E is the Young's modulus (in Pa) of the material of the pipe;

; in which E is the Young's modulus (in Pa) of the material of the pipe; - possibly compressibility Bg of gas dissolved in the liquid, defined by:

- γ being the ratio of specific heats of the gas

- α the rate of ventilation (the volume fraction of undissolved gas)

- and P the pressure (in Pa).

Thus, the effective compressibility modulus is:

As a result, we see that we can reduce the water hammer by:

- increasing the pipe diameter at constant flow, which reduces the inertia of the liquid column;

- choosing to use a material with a reduced Young's modulus;

- introducing a device that increases the flexibility of the entire hydraulic system, such as a hydraulic accumulator;

- where possible, increasing the percentage of undissolved air in the liquid.

Dynamic equations

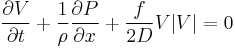

The water hammer effect can be simulated by solving the following partial differential equations.

where V is the fluid velocity inside pipe,  is the fluid density and

is the fluid density and  is the equivalent bulk modulus, f is the friction factor.

is the equivalent bulk modulus, f is the friction factor.

Column separation

Column separation is a phenomenon that can occur during a water-hammer event. If the pressure in a pipeline drops rapidly to the vapor pressure of the liquid, the liquid will vaporise and a "bubble" of vapor will form in the pipeline. This is most likely to occur at specific locations such as closed ends, high points or knees (changes in pipe slope). When the pressure later increases above the vapor pressure of the liquid, the vapor in the bubble returns to a liquid state, which leaves a vacuum in the space formerly occupied by the vapor. The liquid either side of the vacuum is then accelerated into this space by the pressure difference. The collision of the two columns of liquid, (or of one liquid column if at a closed end,) results in Cavitation and cause a large and nearly instantaneous rise in pressure. This pressure rise can damage hydraulic machinery, individual pipes and supporting structures. Many repetitions of cavity formation and collapse may occur in a single water-hammer event.[8]

Simulation software

Most water hammer software packages use the method of characteristics [5] to solve the differential equations involved. This method works well if the wave speed does not vary in time due to either air or gas entrainment in a pipeline. The Wave Method (WM) is also used in various software packages. WM allows large networks to be analyzed efficiently. Many commercial and non commercial packages exist today.

Software packages vary in complexity, dependent on the processes modeled. The more sophisticated packages may have any of the following features:

-

- Multiphase flow capabilities

- An algorithm for cavitation growth and collapse

- Unsteady friction - the pressure waves will dampen as turbulence is generated and due to variations in the flow velocity distribution

- Varying bulk modulus for higher pressures (water will become less compressible)

- Fluid structure interaction - the pipeline will react on the varying pressures and will cause pressure waves itself

Applications

- The water hammer principle can be used to create a simple water pump called a hydraulic ram.

- Leaks can sometimes be detected using water hammer.

- Enclosed air pockets can be detected in pipelines.

See also

References

- ^ Kay, Melvyn (2008). Practical Hydraulics (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-35115-4. http://books.google.com/books?isbn=0415351154&pg=PA120.

- ^ IDO-19313: ADDITIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE SL-1 EXCURSION; Final Report of Progress July through October 1962, November 21, 1962, Flight Propulsion Laboratory Department, General Electric Company, Idaho Falls, Idaho, U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, Division of Technical Information.

- ^ Bruce, S, Larock, E., Jeppson, R W., Watters, G.Z., Hydraulics of Pipeline Systems, CRC Press, 2000, ISBN 0849318068, 9780849318061

- ^ Thorley, ADR, Fluid Transients in Pipelines, 2nd ed. Professional Engineering Publishing, 2004

- ^ a b c Streeter, VL and Wylie, EB, Fluid mechanics, McGraw-Hill Higher Education; International 9th Revised Edition, 1998

- ^ "Water Hammer & Pulsation"

- ^ Faisandier, J., Hydraulic and Pneumatic Mechanisms, 8th edition, Dunod, Paris, 1999 (ISBN 2100499483)

- ^ Bergeron, L., 1950. Du Coup de Bélier en Hydraulique - Au Coup de Foudre en Electricité. (Waterhammer in hydraulics and wave surges in electricity.) Paris: Dunod (in French). (English translation by ASME Committee, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1961.)