WKB approximation

In mathematical physics, the WKB approximation or WKB method is a method for finding approximate solutions to linear partial differential equations with spatially varying coefficients. It is typically used for a semiclassical calculation in quantum mechanics in which the wavefunction is recast as an exponential function, semiclassically expanded, and then either the amplitude or the phase is taken to be slowly changing.

The name is an acronym for Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin. It is also known as the LG or Liouville–Green method. Other often-used acronyms for the method include JWKB and WKBJ, where the "J" stands for Jeffreys.

Contents |

Brief history

This method is named after physicists Wentzel, Kramers, and Brillouin, who all developed it in 1926. In 1923, mathematician Harold Jeffreys had developed a general method of approximating solutions to linear, second-order differential equations, which includes the Schrödinger equation. Even though the Schrödinger equation was developed two years later, Wentzel, Kramers, and Brillouin were apparently unaware of this earlier work, so Jeffreys is often neglected credit. Early texts in quantum mechanics contain any number of combinations of their initials, including WBK, BWK, WKBJ, JWKB and BWKJ.

Earlier references to the method are: Carlini in 1817, Liouville in 1837, Green in 1837, Rayleigh in 1912 and Gans in 1915. Liouville and Green may be said to have founded the method in 1837, and it is also commonly referred to as the Liouville–Green or LG method.[1] [2]

The important contribution of Jeffreys, Wentzel, Kramers and Brillouin to the method was the inclusion of the treatment of turning points, connecting the evanescent and oscillatory solutions at either side of the turning point. For example, this may occur in the Schrödinger equation, due to a potential energy hill.

WKB method

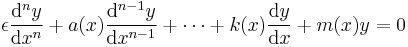

Generally, WKB theory is a method for approximating the solution of a differential equation whose highest derivative is multiplied by a small parameter ε. The method of approximation is as follows:

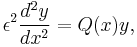

For a differential equation

assume a solution of the form of an asymptotic series expansion

In the limit  . Substitution of the above ansatz into the differential equation and canceling out the exponential terms allows one to solve for an arbitrary number of terms

. Substitution of the above ansatz into the differential equation and canceling out the exponential terms allows one to solve for an arbitrary number of terms  in the expansion. WKB theory is a special case of multiple scale analysis.[3][4][5]

in the expansion. WKB theory is a special case of multiple scale analysis.[3][4][5]

An example

Consider the second-order homogeneous linear differential equation

where  . Substituting

. Substituting

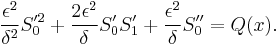

results in the equation

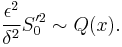

To leading order (assuming, for the moment, the series will be asymptotically consistent) the above can be approximated as

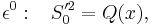

In the limit  , the dominant balance is given by

, the dominant balance is given by

So δ is proportional to ε. Setting them equal and comparing powers renders

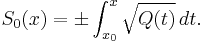

which can be recognized as the Eikonal equation, with solution

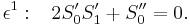

Looking at first-order powers of  gives

gives

This is the unidimensional transport equation, having the solution

where  is an arbitrary constant. We now have a pair of approximations to the system (a pair because

is an arbitrary constant. We now have a pair of approximations to the system (a pair because  can take two signs); the first-order WKB-approximation will be a linear combination of the two:

can take two signs); the first-order WKB-approximation will be a linear combination of the two:

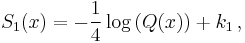

Higher-order terms can be obtained by looking at equations for higher powers of ε. Explicitly

for  . This example comes from Bender and Orszag's textbook (see references).

. This example comes from Bender and Orszag's textbook (see references).

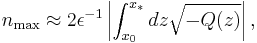

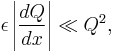

Precision of the asymptotic series

The asymptotic series for  is usually a divergent series whose general term

is usually a divergent series whose general term  starts to increase after a certain value

starts to increase after a certain value  . Therefore the smallest error achieved by the WKB method is at best of the order of the last included term. For the equation

. Therefore the smallest error achieved by the WKB method is at best of the order of the last included term. For the equation

with  an analytic function, the value

an analytic function, the value  and the magnitude of the last term can be estimated as follows (see Winitzki 2005),

and the magnitude of the last term can be estimated as follows (see Winitzki 2005),

where  is the point at which

is the point at which  needs to be evaluated and

needs to be evaluated and  is the (complex) turning point where

is the (complex) turning point where  , closest to

, closest to  . The number

. The number  can be interpreted as the number of oscillations between

can be interpreted as the number of oscillations between  and the closest turning point. If

and the closest turning point. If  is a slowly-changing function,

is a slowly-changing function,

the number  will be large, and the minimum error of the asymptotic series will be exponentially small.

will be large, and the minimum error of the asymptotic series will be exponentially small.

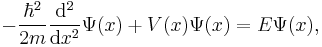

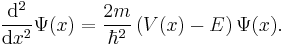

Application to Schrödinger equation

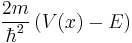

The one dimensional, time-independent Schrödinger equation is

which can be rewritten as

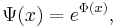

The wavefunction can be rewritten as the exponential of another function Φ (which is closely related to the action):

so that

where  indicates the derivative of

indicates the derivative of  with respect to x. The derivative

with respect to x. The derivative  can be separated into real and imaginary parts by introducing the real functions A and B:

can be separated into real and imaginary parts by introducing the real functions A and B:

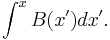

The amplitude of the wavefunction is then ![\exp\left[\int^x A(x')dx'\right]\,\!,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4b73e9a49ab5e63dac52239c3c33ed19.png) while the phase is

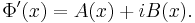

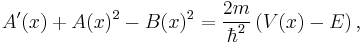

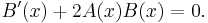

while the phase is  The real and imaginary parts of the Schrödinger equation then become

The real and imaginary parts of the Schrödinger equation then become

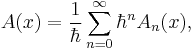

Next, the semiclassical approximation is invoked. This means that each function is expanded as a power series in  . From the equations it can be seen that the power series must start with at least an order of

. From the equations it can be seen that the power series must start with at least an order of  to satisfy the real part of the equation. In order to achieve a good classical limit, it is necessary to start with as high a power of Planck's constant as possible:

to satisfy the real part of the equation. In order to achieve a good classical limit, it is necessary to start with as high a power of Planck's constant as possible:

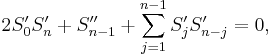

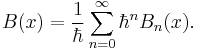

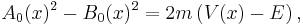

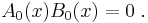

To zeroth-order in this expansion, the conditions on A and B can be written:

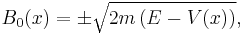

If the amplitude varies sufficiently slowly as compared to the phase ( ), it follows that

), it follows that

which is only valid when the total energy is greater than the potential energy, as is always the case in classical motion. After the same procedure on the next order of the expansion it follows that

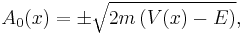

On the other hand, if it is the phase that varies slowly (as compared to the amplitude), ( ) then

) then

which is only valid when the potential energy is greater than the total energy (the regime in which quantum tunneling occurs). Finding the next order of the expansion yields

It is apparent from the denominator, that both of these approximate solutions become singular near the classical turning point where  and cannot be valid. These are the approximate solutions away from the potential hill and beneath the potential hill. Away from the potential hill, the particle acts similarly to a free wave—the wave-function is oscillating. Beneath the potential hill, the particle undergoes exponential changes in amplitude.

and cannot be valid. These are the approximate solutions away from the potential hill and beneath the potential hill. Away from the potential hill, the particle acts similarly to a free wave—the wave-function is oscillating. Beneath the potential hill, the particle undergoes exponential changes in amplitude.

To complete the derivation, the approximate solutions must be found everywhere and their coefficients matched to make a global approximate solution. The approximate solution near the classical turning points  is yet to be found.

is yet to be found.

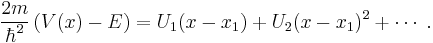

For a classical turning point  and close to

and close to  , the term

, the term  can be expanded in a power series.

can be expanded in a power series.

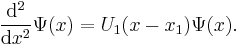

To first order, one finds

This differential equation is known as the Airy equation, and the solution may be written in terms of Airy functions:

This solution should connect the far away and beneath solutions. Given the 2 coefficients on one side of the classical turning point, the 2 coefficients on the other side of the classical turning point can be determined by using this local solution to connect them. Thus, a relationship between  and

and  can be found.

can be found.

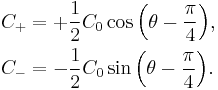

Fortunately the Airy functions will asymptote into sine, cosine and exponential functions in the proper limits. The relationship can be found to be as follows (often referred to as "connection formulas"):

Now the global (approximate) solutions can be constructed.

See also

- Instanton

- Airy Function

- Field electron emission

- Langer correction

- Method of steepest descent / Laplace Method

- Old quantum theory

- Perturbation methods

- Quantum tunneling

- Slowly varying envelope approximation

References

- ^ Adrian E. Gill (1982). Atmosphere-ocean dynamics. Academic Press. p. 297. ISBN 9780122835223. http://books.google.com/?id=1WLNX_lfRp8C&pg=PA297&dq=Liouville-Green+WKBJ+WKB.

- ^ Renato Spigler and Marco Vianello (1998). "A Survey on the Liouville–Green (WKB) approximation for linear difference equations of the second order". In Saber Elaydi, I. Győri, and G. E. Ladas. Advances in difference equations: proceedings of the Second International Conference on Difference Equations : Veszprém, Hungary, August 7–11, 1995. CRC Press. p. 567. ISBN 9789056995218. http://books.google.com/?id=a36iXw5_VzcC&pg=PA567&dq=Liouville-Green+WKBJ+WKB+LG.

- ^ Filippi, Paul (1999). Acoustics: basic physics, theory and methods. Academic Press. p. 171. ISBN 9780122561900. http://books.google.com/?id=xHWiOMp63WsC&pg=PA171&dq=wkb+multi-scale&q=wkb%20multi-scale.

- ^ Kevorkian, J.; Cole, J. D. (1996). Multiple scale and singular perturbation methods. Springer. ISBN 0-387-94202-5.

- ^ Bender, C.M.; Orszag, S.A. (1999). Advanced mathematical methods for scientists and engineers. Springer. pp. 549–568. ISBN 0-387-98931-5.

Modern references

- Razavy, Moshen (2003). Quantum Theory of Tunneling. World Scientific. ISBN 981-238-019-1.

- Griffiths, David J. (2004). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-111892-7.

- Liboff, Richard L. (2003). Introductory Quantum Mechanics (4th ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-8053-8714-5.

- Sakurai, J. J. (1993). Modern Quantum Mechanics. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-53929-2.

- Bender, Carl; Orszag, Steven (1978). Advanced Mathematical Methods for Scientists and Engineers. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-004452-X.

- Olver, Frank J. W. (1974). Asymptotics and Special Functions. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-525850-X.

Historical references

- Carlini, Francesco (1817). Ricerche sulla convergenza della serie che serva alla soluzione del problema di Keplero. Milano.

- Liouville, Joseph (1837). "Sur le développement des fonctions et séries..". Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées 1: 16–35.

- Green, George (1837). "On the motion of waves in a variable canal of small depth and width". Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 6: 457–462.

- Rayleigh, Lord (John William Strutt) (1912). "On the propagation of waves through a stratified medium, with special reference to the question of reflection". Proceedings of the Royal Society London, Series A 86 (586): 207–226. Bibcode 1912RSPSA..86..207R. doi:10.1098/rspa.1912.0014.

- Gans, Richard (1915). "Fortplantzung des Lichts durch ein inhomogenes Medium". Annalen der Physik 47: 709–736.

- Jeffreys, Harold (1924). "On certain approximate solutions of linear differential equations of the second order". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 23: 428–436. doi:10.1112/plms/s2-23.1.428.

- Brillouin, Léon (1926). "La mécanique ondulatoire de Schrödinger: une méthode générale de resolution par approximations successives". Comptes Rendus de l'Academie des Sciences 183: 24–26.

- Kramers, Hendrik A. (1926). "Wellenmechanik und halbzählige Quantisierung". Zeitschrift für Physik 39 (10–11): 828–840. Bibcode 1926ZPhy...39..828K. doi:10.1007/BF01451751.

- Wentzel, Gregor (1926). "Eine Verallgemeinerung der Quantenbedingungen für die Zwecke der Wellenmechanik". Zeitschrift für Physik 38 (6–7): 518–529. Bibcode 1926ZPhy...38..518W. doi:10.1007/BF01397171.

External links

- Fitzpatrick, Richard (2002). "The W.K.B. Approximation". http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/jk1/lectures/node70.html. (An application of the WKB approximation to the scattering of radio waves from the ionosphere.)

![y(x) \sim \exp\left[\frac{1}{\delta}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\delta^nS_n(x)\right].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/633eadbbab82a08d525f2d131dbf081c.png)

![y(x) = \exp\left[\frac{1}{\delta}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\delta^nS_n(x)\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a7c9b8bcb8c0651ee5bb7185710c09a4.png)

![\epsilon^2\left[\frac{1}{\delta^2}\left(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\delta^nS_n'\right)^2 %2B \frac{1}{\delta}\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\delta^nS_n''\right] = Q(x).](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/30ceadf9112ff464edda1ef6bc231f0a.png)

![y(x) \approx c_1Q^{-\frac{1}{4}}(x)\exp\left[\frac{1}{\epsilon}\int_{x_0}^x\sqrt{Q(t)}dt\right] %2B c_2Q^{-\frac{1}{4}}(x)\exp\left[-\frac{1}{\epsilon}\int_{x_0}^x\sqrt{Q(t)}dt\right].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b9ef5934acea09849436c5c05aecf9fc.png)

![\delta^{n_\max}S_{n_\max}(x_0) \approx \sqrt{\frac{2\pi}{n_\max}} \exp[-n_\max],](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ec7657b369c3ad6e6de133b52e3cfa9a.png)

![\Phi''(x) %2B \left[\Phi'(x)\right]^2 = \frac{2m}{\hbar^2} \left( V(x) - E \right),](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0d38c13053c74bca8408f53ba53b6866.png)

![\Psi(x) \approx C_0 \frac{ e^{i \int \mathrm{d}x \sqrt{\frac{2m}{\hbar^2} \left( E - V(x) \right)} %2B \theta} }{\sqrt[4]{\frac{2m}{\hbar^2} \left( E - V(x) \right)}}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6b8d0f188030bfa8e0d379a348aba2b2.png)

![\Psi(x) \approx \frac{ C_{%2B} e^{%2B\int \mathrm{d}x \sqrt{\frac{2m}{\hbar^2} \left( V(x) - E \right)}} %2B C_{-} e^{-\int \mathrm{d}x \sqrt{\frac{2m}{\hbar^2} \left( V(x) - E \right)}}}{\sqrt[4]{\frac{2m}{\hbar^2} \left( V(x) - E \right)}}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/98dee3ee2419b28b08bf426c20db4d0f.png)

![\Psi(x) = C_A \textrm{Ai}\left( \sqrt[3]{U_1} (x - x_1) \right) %2B C_B \textrm{Bi}\left( \sqrt[3]{U_1} (x - x_1) \right).](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1714a6dea70db9cbd0c6acaf0ec4fbd6.png)