Vowel length

| IPA vowel length | |

|---|---|

| aː aˑ | |

| IPA number | 503 or 504 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ːˑ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+02D0 or U+02D1 |

|

|

|

In linguistics, vowel length is the perceived duration of a vowel sound. Often the chroneme, or the "longness", acts like a consonant, and may etymologically be one, such as in Australian English. While not distinctive in most dialects of English, vowel length is an important phonemic factor in many other languages, for instance in Finnish, Fijian, Japanese, Old English, and Vietnamese. It plays a phonetic role in the majority of dialects of English English, and is said to be phonemic in a few other dialects, such as Australian English and New Zealand English. It also plays a lesser phonetic role in Cantonese, which is exceptional among the spoken variants of Chinese.

Many languages do not distinguish vowel length, and those that do usually distinguish between short vowels and long vowels. There are very few languages that distinguish three vowel lengths, for instance Luiseño. Some languages, such as Finnish, Estonian and Japanese, also have words where long vowels are immediately followed by more vowels, e.g. Japanese hōō "phoenix" or Estonian jäääär "ice edge".

Contents |

Stress is often reinforced by allophonic vowel length, especially when it is lexical. For example, French long vowels always occur on stressed syllables. Finnish, a language with two phonemic lengths, indicates the stress by adding allophonic length. This gives four distinctive lengths and five physical lengths: short and long stressed vowels, short and long unstressed vowels, and a half-long vowel, which is a short vowel found in a syllable immediately preceded by a stressed short vowel, e.g. i-so.

Among the languages that have distinctive vowel length, there are some where it may only occur in stressed syllables, e.g. in the Alemannic German dialect and Egyptian Arabic. In languages such as Czech, Finnish or Classical Latin, vowel length is distinctive in unstressed syllables as well.

In some languages, vowel length is sometimes better analyzed as a sequence of two identical vowels. In Finnic languages, such as Finnish, the simplest example follows from consonant gradation: haka → haan. In some cases, it is caused by a following chroneme, which is etymologically a consonant, e.g. jää " ← Proto-Uralic *jäŋe. In noninitial syllables, it is ambiguous if long vowels are vowel clusters — poems written in the Kalevala meter often syllabicate between the vowels, and an (etymologically original) intervocalic -h- is seen in this and some modern dialects (e.g. taivaan vs. taivahan "of the sky"). Morphological treatment of diphthongs is essentially similar to long vowels. Interestingly, some old Finnish long vowels have developed into diphthongs, but successive layers of borrowing have introduced the same long vowels again, such that the diphthong and the long vowel again contrast (e.g. nuotti "musical note" vs. nootti "diplomatic note").

In Japanese, most long vowels are the results of the phonetic change of diphthongs; au and ou became ō, iu became yū, eu became yō, and now ei is becoming ē. The change occurred after the loss of intervocalic phoneme /h/. For example, modern kyōto (Kyoto) exhibits the following changes: kyauto → kyoːto. Another example is shōnen (boy): seunen → syoːnen (shoːnen).

Phonemic vowel length

Many languages make a phonemic distinction between long and short vowels: Sanskrit, Japanese, Finnish, Hungarian, Kannada etc.

Long vowels may or may not be separate phonemes. In Latin and Hungarian, long vowels are separate phonemes from short vowels, thus doubling the number of vowel phonemes.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| High | /ɪ/ | /iː/ | /ʊ/ | /uː/ | ||

| Mid | /ɛ/ | /eː/ | /ɔ/ | /oː/ | ||

| Low | /a/ | /aː/ | ||||

Japanese long vowels are analyzed as either two same vowels or a vowel + the pseudo-phoneme /H/, and the number of vowels is five.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| High | /i/ | /ii/ or /iH/ | /u/ | /uu/ or /uH/ | ||

| Mid | /e/ | /ee/ or /eH/ | /o/ | /oo/ or /oH/ | ||

| Low | /a/ | /aa/ or /aH/ | ||||

Estonian has three distinctive lengths, but the third is suprasegmental, as it has developed from the allophonic variation caused by now-deleted grammatical markers. For example, half-long 'aa' in saada comes from the agglutination *saata+ka "send+(imperative)", and the overlong 'aa' in saada comes from *saa+ta "get+(infinitive)". One of the very few languages to have three lengths, independent of vowel quality or syllable structure, is Mixe. An example from Mixe is [poʃ] "guava", [poˑʃ] "spider", [poːʃ] "knot". Similar claims have been made for Yavapai and Wichita.

Four-way distinctions have been claimed, but these are actually long-short distinctions on adjacent syllables. For example, in kiKamba, there is [ko.ko.na], [kóó.ma̋], [ko.óma̋], [nétónubáné.éetɛ̂] "hit", "dry", "bite", "we have chosen for everyone and are still choosing".

Short and long vowels in English

Vowel length (i.e., "long" and "short"), when applied to English, has several different related meanings.

Traditional long and short vowels in English orthography

Traditionally, the vowels /eɪ iː aɪ oʊ juː/ (as in bait beet bite boat beauty) are said to be the "long" counterparts of the vowels /æ ɛ ɪ ɒ ʌ/ (as in bat bet bit bot but) which are said to be "short". This terminology reflects their pronunciation before the Great Vowel Shift.

Traditional English phonics teaching, at the preschool to first grade level, often used the term "long vowel" for any pronunciation that might result from the addition of a silent E (e.g., like) or other vowel letter as follows:

| Letter | "Short" | "Long" | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| A a | /æ/ | /eɪ/ | "mat" / "mate" |

| E e | /ɛ/ | /iː/ | "pet" / "Pete" |

| I i | /ɪ/ | /aɪ/ | "twin" / "twine" |

| O o | /ɒ/ | /oʊ/ | "not" / "note" |

| U u | /ʌ/ | /juː/ | "cub" / "cube" |

A mnemonic was that each vowel's long sound was its name.

In Middle English, the long vowels /iː, eː, ɛː, aː, ɔː, oː, uː/ were generally written i..e, e..e, ea, a..e, o..e, oo, u..e. With the Great Vowel Shift, they came to be pronounced /aɪ, iː, iː, eɪ, oʊ, uː, aʊ/. Because ea and oo are digraphs, they are not called long vowels today. Under French influence, the letter u was replaced with ou (or final ow), so it is no longer considered a long vowel either. Thus the so-called "long vowels" of Modern English are those vowels written with the help of a silent e.

Allophonic vowel length

In certain dialects of the modern English language, for instance British Received Pronunciation and, to some extent, General American, there is allophonic vowel length: vowel phonemes are realized as longer vowel allophones before voiced consonant phonemes in the coda of a syllable. For example, the vowel phoneme /æ/ in /ˈbæt/ ‘bat’ is realized as a short allophone [æ] in [ˈbæt], because the /t/ phoneme is unvoiced, while the same vowel /æ/ phoneme in /ˈbæd/ ‘bad’ is realized as a slightly long allophone (which could be transcribed as [ˈbæˑd]), because /d/ is voiced. (Incidentally, the final consonant allophones in these syllables also have different relative lengths; the [t] of bat is longer than the [d] of bad.)

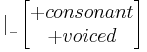

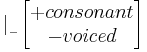

Symbolic representation of the two allophonic rules:

| /æ/ | → | [æˑ] |  |

| /ˈbæd/ | → | [ˈbæˑd] | |

| /æ/ | → | [æ] |  |

| /ˈbæt/ | → | [ˈbæt] |

In addition, the vowels of Received Pronunciation are commonly divided into short and long, as obvious from their transcription. The short vowels are /ɪ/ (as in kit), /ʊ/ (as in foot), /ɛ/ (as in dress), /ʌ/ (as in strut), /æ/ (as in trap), /ɒ/ (as in lot), and /ə/ (as in the first syllable of ago and in the second of sofa). The long vowels are /iː/ (as in fleece), /uː/ (as in goose), /ɜː/ (as in nurse), /ɔː/ as in north and thought, and /ɑː/ (as in father and start). While a different degree of length is indeed present, there are also differences in the quality (lax vs tense) of these vowels, and the currently prevalent view tends to emphasise the latter rather than the former.

Contrastive vowel length

In Australian English, there is contrastive vowel length in closed syllables between long and short /e æ ä/ and sometimes /ɪ/. The following can be minimal pairs of length for many speakers:

| [bɪd] bid | vs | [bɪːd] as in beard |

| [feɹi] ferry | vs | [feːɹi] fairy |

| [kæn] can meaning able to | vs | [kæːn] as in tin can |

| [kät] cut | vs | [käːt] cart |

Origin

The long vowel may often be traced to assimilation. In Australian English, the second element [ə] of a diphthong [eə] has assimilated to the preceding vowel, giving the pronunciation of bared as [beːd], creating a contrast with bed [bed]. Another etymology is the vocalization of a fricative such as the voiced velar fricative or voiced palatal fricative, e.g. Finnish illative case, or even an approximant, as the English 'r'.

Estonian, of Finnic languages, exhibits a rare phenomenon, where allophonic length variation becomes phonemic following the deletion of the suffixes causing the allophony. Estonian already distinguishes two vowel lengths, but a third one has been introduced by this phenomenon. For example, the Finnic imperative marker *-k caused the preceding vowels to be articulated shorter, and following the deletion of the marker, the allophonic length became phonemic, as shown in the example below. Similarly, the Australian English phoneme /æː/ was created by the incomplete application of a rule extending /æ/ before certain voiced consonants, a phenomenon known as the bad–lad split.

Many long vowels in the Indo-European languages were formed from short vowels and one of the laryngeal sounds, conventionally written h1, h2 and h3. If a laryngeal followed a vowel in Proto-Indo-European, it was usually lost in its later descendants and the preceding vowel became long. However, Proto-Indo-European itself already possessed long vowels as well, usually as the result of older sound changes such as Szemerényi's law and Stang's law.

Notations in the Latin alphabet

IPA

In the International Phonetic Alphabet the sign ː (not a colon, but two triangles facing each other in an hourglass shape; Unicode U+02D0) is used for both vowel and consonant length. This may be doubled for an extra-long sound, or the top half (ˑ) used to indicate a sound is "half long". A breve is used to mark a short vowel or consonant.

Estonian has a three-way phonemic contrast:

- saada [saːta] "to get"

- saada [saˑta] "send!"

- sada [sata] "hundred"

Although not phonemic, the distinction can also be illustrated in certain accents of English:

- bead [biːd]

- beat [biˑt]

- bid [bɪˑd]

- bit [bɪt]

Diacritics

- Macron (ā), used to indicate a long vowel in Maori, Hawaiian, Samoan, Latvian and many transcription schemes, including romanizations for Sanskrit and Arabic, the Hepburn romanization for Japanese, and Yale for Korean. While not part of their standard orthography, the macron is also used as a teaching aid in modern Latin and Ancient Greek textbooks.

- Breves (ă) are used to mark short vowels in several linguistic transcription systems, as well as in Vietnamese.

- Acute accent (á), used to indicate a long vowel in Czech, Slovak, Old Norse, Hungarian and Irish.

- Circumflex (â), used for example in Welsh. The circumflex is occasionally used as a surrogate for the macrons, particularly in the Kunrei-shiki romanization of Japanese.

- Grave accent (à) is used in Scottish Gaelic.

- Ogonek (ą), used in Lithuanian to indicate long vowels.

- Umlaut mark (ä), used in Aymara to indicate long vowels.

Additional letters

- Vowel doubling, used consistently in Estonian, Finnish, Lombard and in closed syllables in Dutch. Example: Finnish tuuli /ˈtuːli/ 'wind' vs. tuli /ˈtuli/ 'fire'.

- Estonian also has a rare "overlong" vowel length, but does not distinguish this from the normal long vowel in writing; see the example below.

- Consonant doubling after short vowels is very common in Swedish and other Germanic languages, including English. The system is somewhat inconsistent, especially in loan-words, around consonant clusters and with word final nasal consonants. Examples:

- Consistent use: byta /ˈbyːta/ 'to change' vs bytta /ˈbyta/ 'tub' and koma /ˈkoːma/ 'coma' vs komma /ˈkoma/ 'to come'

- Inconsistent use: fält /ˈfɛlt/ 'a field' and kam /ˈkam/ 'a comb' (but the verb 'to comb' is kamma)

- Classical Milanese orthography uses consonant doubling in closed short syllables, e.g., lenguagg 'language' and pubblegh 'public'.[1]

- ie is used to mark the long /iː/ sound in German. This is due to the preservation and generalization of a historical ie spelling that originally represented the sound /iə̯/. In northern German, a following e letter lengthens other vowels as well, e.g., in the name Kues /kuːs/.

- A following h is frequently used in German and older Swedish spelling, e.g., German Zahn [tsaːn] 'tooth'.

- In Czech, the additional letter ů is used for the long U sound, where the character is known as a kroužek, e.g., kůň "horse". (This actually developed from the ligature "uo", which signified the diphthong /uo/, which later shifted to /uː/.)

Other signs

- Apostrophe, used in Mi'kmaq, as evidenced by the name itself. This is the convention of the Listuguj orthography (Mi'gmaq), and a common substitution for the official acute accent (Míkmaq) of the Francis-Smith orthography.

- Colon (punctuation), commonly used as an approximation of the IPA phonetic transcription, and in a few orthographies based on the IPA.

- Interpunct, commonly used in non-IPA phonetic transcription, such as the Americanist system developed by linguists for transcribing the indigenous languages of the Americas. Example: Americanist [tʰo·] = IPA [tʰoː].

No distinction

Some languages make no distinction in writing. This is particularly the case with ancient languages such as Latin and Old English. Modern edited texts often use macrons with long vowels, however. Australian English does not distinguish the vowels /æ/ from /æː/ in spelling, with words like ‘span’ or ‘can’ having different pronunciations depending on meaning.

Notations in other writing systems

In non-Latin writing systems, a variety of mechanisms have also evolved.

- In abjads derived from the Aramaic alphabet, notably Arabic and Hebrew, long vowels are written with consonant letters (mostly approximant consonant letters) in a process called mater lectionis, while short vowels are typically omitted entirely. Most of these scripts also have optional diacritics that can be used to mark short vowels when needed.

- In South-Asian abugidas, such as Devanagari or the Thai alphabet, there are different vowel signs for short and long vowels.

- In the Japanese hiragana syllabary, long vowels are usually indicated by adding a vowel character after. For vowels /aː/, /iː/, and /uː/, the corresponding independent vowel is added. Thus: あ (a), おかあさん, "okaasan", mother; い (i), にいがた "Niigata", city in northern Japan (usu. 新潟, in kanji); う (u), りゅう "ryuu" (usu. 竜), dragon. The mid-vowels /eː/ and /oː/ may be written with え (e) (rare) (ねえさん (姉さん), neesan, "elder sister") and お (o) [おおきい (usu 大きい), ookii, big] , or with い (i) (めいれい (命令), "meirei", command/order) and う (u) (おうさま (王様), ousama, "king") depending on etymological, morphological, and historic grounds.

- Most long vowels in the katakana syllabary are written with a special bar symbol ー (vertical in vertical writing), called a chōon, as in メーカー mēkā "maker" instead of メカ meka "mecha". However, some long vowels are written with additional vowel characters, as with hiragana, with the distinction being orthographically significant.

- In the Korean Hangul alphabet, vowel length is not distinguished in normal writing. Some dictionaries use a double dot, ⟨:⟩, for example 무: “Daikon radish”.

References

- ^ Carlo Porta on the Italian Wikisource

|

|||||||||||||||||