François Viète

| François Viète | |

|---|---|

François Viète, French mathematician

|

|

| Born | 1540 Fontenay-le-Comte, Vendée, France |

| Died | 23 February 1603 (aged 62-63) Paris, France |

| Fields | algebra |

| Known for | first notation of new algebra |

| Influences | Ramus |

| Influenced | Pierre de Fermat |

| Signature |

|

François Viète (Latin: Franciscus Vieta; 1540 – 23 February 1603), Seigneur de la Bigotière, was a French mathematician whose work on new algebra was an important step towards modern algebra, due to its innovative use of letters as parameters in equations. He was a lawyer by trade, and served as a privy councillor to both Henry III and Henry IV.

Contents |

Biography

Origins

Viete was born at Fontenay-le-Comte, Vendée. His grandfather was a merchant from La Rochelle. His father, Etienne Viète, was an attorney in Fontenay-le-Comte and a notary in Le Busseau. His mother was the aunt of Barnabé Brisson, a magistrate and the first president of parliament during the ascendancy of the Catholic League of France.

Vieta went to a Franciscan school and in 1558 studied law at Poitiers, graduating as a Bachelor of Law in 1559. A year later, he began his career as an attorney in his native town. From the outset, he was entrusted with some major cases, including the settlement of rent in Poitou for the widow of King Francis I of France and looking after the interests of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Serving Parthenay

In 1564, Vieta entered the service of Antoinette d’Aubeterre, Lady Soubise, wife of Jean V de Parthenay-Soubise, one of the main Huguenot military leaders and accompanied him to Lyon to collect documents about his heroic defence of that city against the troops of Jacques of Savoy, 2nd Duke of Nemours just the year before.

The same year, at Parc-Soubise, in the commune of Mouchamps, Vendée, Vieta became the tutor of Catherine de Parthenay, Soubise's eleven-year-old daughter. He taught her science and mathematics and wrote for her numerous treatise on astronomy, geography and trigonometry, some of which have survived. In these treatise, Vieta used decimal numbers (twenty years before Stevin's paper) and he also noted the elliptic orbit of the planets, forty years before Kepler and twenty years before Giordano Bruno's death.

John V de Parthenay presented him to King Charles IX of France. Vieta wrote a genealogy of the Parthenay family and following the death of Jean V de Parthenay-Soubise in 1566, his biography.

In 1568, Antoinette, Lady Soubise, married her daughter Catherine to Baron Charles de Quellenec and Vieta went with Lady Soubise to La Rochelle, where he mixed with the highest Calvinist aristocracy, leaders like Coligny and Condé and Queen Jeanne d’Albret of Navarre and her son, Henry of Navarre, the future Henry IV of France.

In 1570, he refused to represent the Soubise ladies in their infamous lawsuit against the Baron De Quellenec, where they claimed the Baron was unable (or unwilling) to provide an heir.

First steps in Paris

In 1571, he enrolled as an attorney in Paris, and continued to visit his student Catherine. He regularly lived in Fontenay-le-Comte, where he took on some municipal functions. He began publishing his Universalium inspectionum ad canonem mathematicum liber singularis and wrote new mathematical research by night or during periods of leisure. He was known to dwell on any one question for up to three days, his elbow on the desk, feeding himself without changing position (according to his friend, Jacques de Thou).[1]

In 1572, Vieta was in Paris during the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. That night, Baron De Quellenec was killed after having tried to save Admiral Coligny the previous night. The same year, Vieta met Françoise de Rohan, Lady of Garnache, and became her adviser against Jacques, Duke of Nemours.

In 1573, he became a councillor of the Parliament of Brittany, at Rennes, and two years later, he obtained the agreement of Antoinette d'Aubeterre for the marriage of Catherine of Parthenay to Duke René de Rohan, Françoise's brother.

In 1576, Henri, duc de Rohan took him under his special protection, recommending him in 1580 as "maître des requêtes". In 1579, Vieta printed his canonem mathematicum (Metayer publisher). A year later, he was appointed maître des requêtes to the parliament of Paris, committed to serving the king. That same year, his success in the trial between the Duke of Nemours and Françoise de Rohan, to the benefit of the latter, earned him the resentment of the tenacious Catholic League.

Exile in Fontenay

Between 1583 and 1585, the League persuaded Henry III to release Vieta, Vieta having been accused of sympathy with the Protestant cause. Henry of Navarre, at Rohan's instigation, addressed two letters to King Henry III of France on March 3 and April 26, 1585, in an attempt to obtain Vieta's restoration to his former office; he failed.

Vieta retired to Fontenay and Beauvoir-sur-Mer, with François de Rohan. He spent four years devoted to mathematics, writing his "Analytical Art" or New Algebra.

Code-breaker to two kings

In 1589, Henry III took refuge in Blois. He commanded the royal officials to be at Tours before 15 April 1589. Vieta was one of the first who came back to Tours. He deciphered the secret letters of the Catholic League and other enemies of the king. Later, he had arguments with the classical scholar Joseph Juste Scaliger. Vieta triumphed against him in 1590.

After the death of Henry III, Vieta became a Privy Councillor to Henry of Navarre, now Henry IV. He was appreciated by the king, who admired his mathematical talents. Vieta was given the position of councillor of the parlement at Tours. In 1590, Vieta discovered the key to a Spanish cipher, consisting of more than 500 characters, and this meant that all dispatches in that language which fell into the hands of the French could be easily read.

Henry IV published a letter from Commander Moreo to the king of Spain. The contents of this letter, read by Vieta, revealed that the head of the League in France, the Duke of Mayenne, planned to become king in place of Henry IV. This publication led to the settlement of the Wars of Religion. The king of Spain accused Vieta of having used magical powers. In 1593, Vieta published his arguments against Scaliger. Beginning in 1594, he was appointed exclusively deciphering the enemy's secret codes.

Gregorian calendar

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII published his bull Inter gravissimas and ordered the Catholic kings to comply with the change from the Julian calendar, based on the calculations of the Calabrian doctor Aloysius Lilius or Giglio. His work was resumed, after his death, by the scientific adviser to the Pope, Christopher Clavius.

Vieta accused Clavius, in a series of pamphlets (1600), of introducing corrections and intermediate days in an arbitrary manner, and misunderstanding the meaning of the works of his predecessor, particularly in the calculation of the lunar cycle. Vieta gave a new timetable, which Clavius cleverly refuted,[2] after Vieta's death, in his Explicatio (1603).

It is said that Vieta was wrong. Without doubt, he believed himself be a kind of "King of Times" as the historian of mathematics, Dhombres, claimed.[3] It is true that Vieta held Clavius in low esteem, as evidenced by De Thou:

He said that Clavius was very clever to explain the principles of mathematics, that he heard with great clarity what the authors had invented, and wrote various treaties compelling what had been written before him without quoting its referencies. So, his works were in a better order which was scattered and confused in early writings...

The Adriaan van Roomen affair

In 1594, Scaliger resumed his attacks from the University of Leyden. Vieta replied definitively the following year. In March that same year, Adriaan van Roomen sought the resolution, by any of Europe's top mathematicians, to a polynomial equation of degree 45. King Henri IV received a snub from the Dutch ambassador, who claimed that there was no mathematician in France. He said it was simply because some Dutch mathematician, Adriaan van Roomen, had not asked any Frenchman to solve his problem.

Vieta came, saw the problem, and, after leaning on a window for a few minutes, solved it. It was the equation between sin(x) and sin(x/45). He resolved this at once, and said he was able to give at the same time (actually the next day) the solution to the other 22 problems to the ambassador. "Ut legit, ut solvit", he later said. Further, he sent a new problem back to Van Roomen, for resolution by Euclidean tools (rule and compass) of the lost answer to the problem first set by Apollonius of Perga. Van Roomen could not overcome that problem without resorting to a trick (see detail below).

Final years

In 1598, Vieta was granted special leave. Henry IV, however, charged him to end the revolt of the Notaries, whom the King had ordered to pay back their fees. Sick and exhausted by work, he left the King's service in December 1602 and received 20,000 écu, which were found at his bedside after his death.

A few weeks before his death, he wrote a final thesis on issues of cryptography, whose memory made obsolete all encryption methods of the time. He died on 23 February 1603, as wrote De Thou,[4] leaving two daughters, Jeanne, born from Barbe Cottereau and Suzanne, born from Julienne Leclerc. Jeanne, the eldest, died in 1628, having married Jean Gabriau, a councillor of the parlement of Brittany. Suzanne died in January 1618 in Paris. The cause of Vieta's death is unknown. Alexander Anderson, student of Vieta and publisher of his scientific writings, speaks of a "praeceps et immaturum autoris fatum."[5]

Work and thought

A new algebra

At the end of 16th century, mathematics was placed under the dual aegis of the Greeks, from whom they borrowed the tools of geometry, and the Arabs, who provided procedures for the resolution. At the time of Vieta, algebra therefore oscillated between arithmetic, which gave the appearance of a list of rules, and geometry which seemed more rigorous. Meanwhile, Italian mathematicians Luca Pacioli, Scipione del Ferro, Niccolo Fontana Tartaglia, Ludovico Ferrari, and especially Raphael Bombelli (1560) all developed techniques for solving equations of the third degree, which heralded a new era.

On the other hand, the German school of the Coss, the English mathematician Robert Recorde (1550) and the Dutchman Simon Stevin (1581) brought an early algebraic notation, the use of decimals and exponents. However, complex numbers remained at best a philosophical way of thinking and Descartes, almost a century after their invention, used them as imaginary numbers. Only positive solutions were considered and using geometrical proof was common.

The task of the mathematicians was in fact twofold. It was necessary to produce algebra in a more geometrical way, i.e. to give it a rigorous foundation and, on the other hand, it was necessary to give geometry a more algebraic sense, allowing the analytical calculation in the plane. Vieta and Descartes solved this dual task in a double revolution. Firstly, Vieta gave algebra a foundation as strong as in geometry. He then ended the algebra of procedures (al-Jabr and Muqabala), creating the first symbolic algebra. In doing so, he did not hesitate to say that with this new algebra, all problems could be solved (nullum non problema solvere).[6][7]

In his dedication of the Isagoge to Catherine de Parthenay, Vieta wrote, "These things which are new are wont in the beginning to be set forth rudely and formlessly and must then be polished and perfected in succeeding centuries. Behold, the art which I present is new, but in truth so old, so spoiled and defiled by the barbarians, that I considered it necessary, in order to introduce an entirely new form into it, to think out and publish a new vocabulary, having gotten rid of all its pseudo-technical terms…"[8]

Vieta did not know "multiplied" notation (given by William Oughtred in 1631) or the symbol of equality, = , an absence which is more striking because Robert Recorde had used the present symbol for this purpose since 1557 and Guilielmus Xylander had used parallel vertical lines since 1575.

Vieta had neither much time, nor students able to brilliantly illustrate his method. He took years in publishing his work, (he was very meticulous) and most importantly, he made a very specific choice to separate the unknown variables, using consonants for parameters and vowels for unknowns. In this notation he perhaps followed some older contemporaries, such as Petrus Ramus, who designated the points in geometrical figures by vowels, making use of consonants, R, S, T, etc., only when these were exhausted. This choice proved disastrous for readability and Descartes, in preferring the first letters to designate the parameters, the latter for the unknowns, showed a greater knowledge of the human heart.

Vieta also remained prisoner of his time in several respects: First, he was heir of Ramus and did not address the lengths as numbers. His writing kept track of homogeneity, which did not simplify their reading. He failed to recognize the complex numbers of Bombelli and needed to doublecheck his algebraic answers through geometrical construction. Although he was fully aware that his new algebra was sufficient to give a solution, this concession tainted his reputation.

However, Vieta created many innovations: the binomial formula, which would be taken by Pascal and Newton, and the link between the roots and coefficients of a polynomial, called Vieta's formula.

Vieta was well skilled in most modern artifices, aiming at the simplification of equations by the substitution of new quantities having a certain connection with the primitive unknown quantities. Another of his works, Recensio canonica effectionum geometricarum, bears a modern stamp, being what was later called an algebraic geometry—a collection of precepts how to construct algebraic expressions with the use of ruler and compass only. While these writings were generally intelligible, and therefore of the greatest didactic importance, the principle of homogeneity, first enunciated by Vieta, was so far in advance of his times that most readers seem to have passed it over. That principle had been made use of by the Greek authors of the classic age; but of later mathematicians only Hero, Diophantus, etc., ventured to regard lines and surfaces as mere numbers that could be joined to give a new number, their sum.

The study of such sums, found in the works of Diophantus, may have prompted Vieta to lay down the principle that quantities occurring in an equation ought to be homogeneous, all of them lines, or surfaces, or solids, or supersolids—an equation between mere numbers being inadmissible. During the centuries that have elapsed between Vieta's day and the present, several changes of opinion have taken place on this subject. Modern mathematicians like to make homogeneous such equations as are not so from the beginning, in order to get values of a symmetrical shape. Vieta himself did not see that far; nevertheless, he indirectly suggested the thought. He also conceived methods for the general resolution of equations of the second, third and fourth degrees different from those of Scipione dal Ferro and Lodovico Ferrari, with which he had not been acquainted. He devised an approximate numerical solution of equations of the second and third degrees, wherein Leonardo of Pisa must have preceded him, but by a method which was completely lost.

Above all, Vieta was the first mathematician who introduced notations for the problem (and not just for the unknowns).[6] As a result, his algebra was no longer limited to the statement of rules, but relied on an efficient computer algebra, in which the operations act on the letters and the results can be obtained at the end of the calculations by a simple replacement. This approach, which is the heart of contemporary algebraic method, was a fundamental step in the development of mathematics.[9] With this, Vieta marked the end of medieval algebra (from Al-Khwarizmi to Stevin) and opened the modern period.

The logic of species

Being wealthy, Vieta began to publish at his own expense, for a few friends and scholars in almost every country of Europe, the systematic presentation of his mathematic theory, which he called "species logistic" (from specis: symbol) or art of calculation on symbols (1591).[10]

He described in three stages how to proceed for solving a problem:

- As a first step, he summarized the problem in the form of an equation. Vieta called this stage the Zetetic. It denotes the known quantities by consonants (B, D, etc.) and the unknown quantities by the vowels (A, E, etc.)

- In a second step, he made an analysis. He called this stage the Poristic. Here mathematicians must discuss the equation and solve it. It gives the characteristic of the problem, porisma, from which we can move to the next step.

- In the last step, the exegetical analysis, he returned to the initial problem which presents a solution through a geometrical or numerical construction based on porisma.

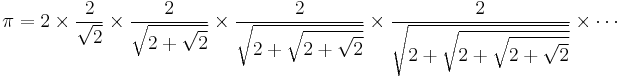

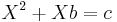

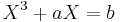

Among the problems addressed by Vieta with this method is the complete resolution of the quadratic equations of the form  and third-degree equations of the form

and third-degree equations of the form  (Vieta reduced it to quadratic equations). He knew the connection between the positive roots of an equation (which, in his day, were alone thought of as roots) and the coefficients of the different powers of the unknown quantity (see Viète's formulas and their application on quadratic equations). He discovered the formula for deriving the sine of a multiple angle, knowing that of the simple angle with due regard to the periodicity of sines. This formula must have been known to Vieta in 1593.

(Vieta reduced it to quadratic equations). He knew the connection between the positive roots of an equation (which, in his day, were alone thought of as roots) and the coefficients of the different powers of the unknown quantity (see Viète's formulas and their application on quadratic equations). He discovered the formula for deriving the sine of a multiple angle, knowing that of the simple angle with due regard to the periodicity of sines. This formula must have been known to Vieta in 1593.

Adriaan van Roomen's problem

This famous controversy is told by Tallemant des Réaux in these terms (46 stories):

"In the times of Henri the fourth, a Dutchman called Adrianus Romanus, a learned mathematician, but not so good as he believed, published a treatise in which he proposed a question to all the mathematicians of Europe, but did not ask any Frenchman. Shortly after, a state ambassador came to the King at Fontainebleau. The King took pleasure in showing him all the sights, and he said people there were excellent in every profession in his kingdom. 'But, Sire,' said the ambassador, 'you have no mathematician, according to Adrianus Romanus, who didn't mention any in his catalog.' 'Yes, we have,' said the King. 'I have an excellent man. Go and seek Monsieur Viette,' he ordered. Vieta, who was at Fontainebleau, came at once. The ambassador sent for the book from Adrianus Romanus and showed the proposal to Vieta, who had arrived in the gallery, and before the King came out, he had already written two solutions with a pencil. By the evening he had sent many other solutions to the ambassador."

This suggests that the Adrien van Roomen problem is an equation of 45°, which Vieta recognized immediately as a chord of an arc of 8° ( radians). It was then easy to determine the following 22 positive alternatives, the only valid ones at the time.

radians). It was then easy to determine the following 22 positive alternatives, the only valid ones at the time.

When, in 1595, Vieta published his response to the problem set by Adriaan van Roomen, he proposed finding the resolution of the old problem of Apollonius, namely to find a circle tangent to three given circles. Van Roomen proposed a solution using an hyperbola, with which Vieta did not agree, as he was hoping for a solution using Euclidean tools).

Vieta published his own solution in 1600, (Apollonius Gallus). In this paper, Vieta made use of the center of similitude of two circles. His friend De Thou said that Adriaan van Roomen immediately left the University of Würzburg, saddled his horse and went to Fontenay-le-Comte, where Vieta lived. According to De Thou, he stayed a month with him, and learned the methods of the new algebra. The two men became friends and Vieta paid all van Roomen's expenses before his return to Würzburg.

This resolution had an almost immediate impact in Europe and Vieta earned the admiration of many mathematicians over the centuries. Vieta did not deal with cases (circles together, these tangents, etc.), but recognized that the number of solutions depends on the relative position of the three circles and outlined the ten resulting situations. Descartes completed (in 1643) the theorem of the three circles of Apollonius, leading to a quadratic equation in 87 terms, each of which is a product of six factors (which, with this method, makes the actual construction humanly impossible).[11]

Works

- Between 1564 and 1568, Vieta prepared for his student, Catherine de Parthenay, some textbooks of astronomy and trigonometry and a treaty that was never published: Harmonicon coelestis.

- From 1571, he published at his own expense and with great printing difficulties:

- Francisci Vietœi universalium inspectionum ad canonem mathematicum liber singularis; a book of trigonometry, in abbreviated Canonen mathematicum, where there are many formulas on the sine and cosine. It is unusual in using decimal numbers. These trigonometric tables exceeded those of Regiomontanus (Triangulate Omnimodis, 1533) and Rheticus (1543, annexed to De revolutionibus ... of Copernicus).

- In 1589: Deschiffrement escription of a letter by the Commander Moreo at Roy Espaigne of his master. Tours, Mettayer, 1590, p. 20

- Two versions of the Isagoge:

- Francisci Vietae-in artem analyticem isagoge. Tours, Mettayer, 1591, 9 fol-Francisci Vietae Fontenaeensis in artem analyticem isagoge. Ejusdem ad logisticem speciosam Notae priors. Paris, Baudry, 1631, in 12, 233 p.

- In Artem Analyticien Isagoge (Introduction to the art of analysis), considered as the founding text of the analysis (in contrast to the summary).

- Francisci Vietae Zeteticorum libri quinque. Tours, Mettayer, folio 24, which are the five books of Zetetic. This is a collection of problems from Diophantus, and solved using the analytical art.

- Effectionum geometricarum canonica recensio. Sd, fol 7. Undated.

- In 1593, Vietae Supplementum geometriae. Tours Francisci, 21 fol.

The same year:

- Francisci Vietae Variorum de rebus responsorum mathematics liber VIII. Tours, Mettayer, 1593, 49 fol about the challenges of Scaliger. The following year, he will give the same against Scaliger: Munimen adversus nova cyclometrica. Paris, Mettayer, in 4, 8 fol.

- The Eighth Book of the varied responses, in which he talks about the problems of the trisection of the angle (which he acknowledges that it is bound to an equation of third degree) of squaring the circle, building the regular heptagon, etc.

The same year, based on geometrical considerations and through trigonometric calculations perfectly mastered, he discovered the first infinite product in history of mathematics by giving an expression of π:

He provides 10 decimal places of π by applying the Archimedes method to a polygon with 6 × 216 = 393 216 sides.

In 1595: Ad mathematics problema quod omnibus totius orbis construendum proposuit Adrianus Romanus, Vietae responsum Francisci. Paris, Mettayer, in 4, 16 fol; text about the Adriaan van Roomen problem.

In 1600, numbers potestatum ad exegesim resolutioner. Paris, Le Clerc, 36 fol; work that provided the means for extracting roots and solutions of equations of degree at most 6.

Francisci Vietae Apollonius Gallus. Paris, Le Clerc, in 4, 13 fol., where he referred to himself as the French Apollonius.

In 1602, Francisci Vietae Fontenaeensis libellorum supplicum Regia magistri in relatio Kalendarii Gregorian vere ad ecclesiasticos doctores exhibits Pontifici Maximi Clementi VIII. Anno Christi I600 jubilaeo. Paris, Mettayer, in 4, fol 40

Francisci and Vietae adversus Christophorum Clavium expostulatio. Paris, Mettayer, in 4, 8 p exposing his theses against Clavius.

His convictions

Vieta was accused of Protestantism by the Catholic League, but he was not a Huguenot (his father was, according to Dhombres)[12] Indifferent in religious matters, he did not adopt the Calvinist faith of Parthenay, nor that of his other protectors, the Rohan family. His call to the parliament of Rennes proved the opposite. At the reception as a member of the court of Brittany, on 6 April 1574, he read in public a statement of Catholic faith.[12]

Nevertheless, Vieta defended and protected Protestants his whole life, and suffered, in turn, the wrath of the League. It seems that for him, the stability of the state must be preserved and that under this requirement, the King's religion did not matter. At that time, such people were called "Politicals."

Furthermore, at his death, he did not want to confess his sins. A friend had to convince him that his own daughter would not find a husband, were he to refuse the sacraments of the Catholic Church. Whether Vieta was an atheist or not is a matter of debate.[12]

Posterity

During the ascendancy of the Catholic League, Vieta's secretary was Nathaniel Tarporley, perhaps one of the more interesting and enigmatic mathematicians of 16th century England. When he returned to London, Tarporley became one of the trusted friends of Thomas Harriot.

Apart from Catherine de Parthenay, Vieta's other notable students were: French mathematician Jacques Aleaume, from Orleans, Marino Ghetaldi of Ragusa, Jean de Beaugrand and the Scottish mathematician Alexander Anderson. They illustrated his theories by publishing his works and continuing his methods. At his death, his heirs gave his manuscripts to Peter Aleaume.[13] We give here the most important posthumous editions:

- In 1612: Supplementum Apollonii Galli of Marino Ghetaldi.

- From 1615 to 1619: Animadversionis in Franciscum vietam, Clemente a Cyriaco nuper by Alexander Anderson

- Francisci Vietae Fontenaeensis ab aequationum recognitione et emendatione Tractatus duo Alexandrum per Andersonum. Paris, Laquehay, 1615, in 4, 135 p. The death of Alexander Anderson unfortunately halted the publication.

- In 1630, an Introduction to Art of new analytic algebra, translated into French and commentary by mathematician JL Sieur de Vaulezard. Paris, Jacquin.

- The five books of François Viette's Zetetic, put into French, and commented increased by mathematician JL Sieur de Vaulezard. Paris, Jacquin, p. 219.

The same year, there appeared an Isagoge by Antoine Vasset (a pseudonym of Claude Hardy), and the following year, a translation into Latin of Beaugrand, which Descartes would have received.

In 1648, the corpus of mathematical works printed by Frans van Schooten, professor at Leiden University (Elzevirs presses). He was assisted by Jacques Golius and Mersenne.

The English mathematicians Thomas Harriot and Isaac Newton, and the Dutch physicist Willebrord Snellius, the French mathematicians Pierre de Fermat and Blaise Pascal all used Vieta's ratings. Later, Leibniz sought to analyze what Vieta had done for equations but his fame was soon eclipsed by René Descartes, who, despite the efforts of scholars like D'Alembert, obtained the full paternity of analytical geometry.

About 1770, the Italian mathematician Targioni Tozzetti, found in Florence an Harmonicum. Vieta had written in it: Describat Planeta Ellipsim ad motum anomaliœ ad Terram. (That shows he adopted Copernic's system and understood before Kepler the elliptic form of the orbits of planets) [14]

In 1841, the French mathematician, Michel Chasles was one of the first to reevaluate his role in the development of modern algebra.

In 1847, a letter from François Arago, perpetual secretary of the Academy of Sciences (Paris) announced his intention to write a biography of Franciscus Vieta.

Between 1880 and 1890, the polytechnician Fréderic Ritter, based in Fontenay-le-Comte, was the first translator of the works of François Viète and his first contemporary biographer with Benjamin Fillon.

Descartes' opinion of Vieta

Thirty four years after the death of Vieta, the philosopher René Descartes published his method and a book of geometry that changed the landscape of algebra and built on Vieta's work, applying it to the geometry by removing its requirements of homogeneity. Descartes, accused by Jean Baptiste Chauveau, a former classmate of La Flèche, explained in a letter to Mersenne (1639 February) that he never read those works.[15]

"I have no knowledge of this surveyor and I wonder what he said, that we studied Vieta's work together in Paris, because it is a book which I cannot remember having seen the cover, while I was in France."

Elsewhere, Descartes said that Vieta's notations were confusing and used unnecessary geometric justifications. In some letters, he showed he understands the program of the Artem Analyticem Isagoge; in others, he shamelessly caricatured Vieta's proposals. One of his biographers, Charles Adam,[16] noted this contradiction:

"These words are surprising, by the way, for he (Descartes) had just said a few lines earlier that he had tried to put in his geometry only what he believed "was known neither by Vieta nor by anyone else". So he was informed of what Vieta knew; and he must have read his works previously."

Current research has not shown the extent of the direct influence of the works of Vieta on Descartes. This influence could have been formed through the works of Adriaan van Roomen or Jacques Aleaume at the Hague, or through the book by Jean de Beaugrand.[17]

In his letters to Mersenne, Descartes consciously minimized the originality and depth of the work of his predecessors. "I began," he says, "where Vieta finished". His views emerged in the 17th century and mathematicians won a clear algebraic language without the requirements of homogeneity. Many contemporary studies have restored the work of Parthenay's mathematician, showing he had the double merit of introducing the first elements of literal calculation and build a first axiomatic for algebra.

Although Vieta was not the first to propose notation of unknown quantities by letters (Jordanus Nemorarius had done it in the past), we can reasonably estimate that it would be simplistic to summarize his innovations for that discovery and place him at the junction of algebraic transformations made during the late sixteenth - early 17th century.

See also

Notes

- ^ Kinser, Sam. The works of Jacques-Auguste de Thou. Google Books

- ^ Clavius, Christophorus. 0perum mathematicorum tomus quintus continens Romani Christophorus Clavius, published by Anton Hierat, Johann Volmar, place Royale Paris, in 1612

- ^ Otte, Michael; Panza, Marco. Analysis and synthesis in mathematics. Google Books

- ^ De thou (from University of Saint Andrews)

- ^ Ball, Walter William Rouse. A short account of the history of mathematics. Google Books

- ^ a b H. J. M. Bos : Redefining geometrical exactness: Descartes' transformation Google Books

- ^ Jacob Klein: Greek mathematical thought and the origin of algebra, Google Books

- ^ Hadden, Richard W. (1994), On the Shoulders of Merchants: Exchange and the Mathematical Conception of Nature in Early Modern Europe, New York: State University of New York Press, ISBN 058504483X.

- ^ Helena M. Pycior : Symbols, Impossible Numbers, and Geometric Entanglements: British Algebra... Google books

- ^ Peter Murphy, Peter Murphy (LL. B.) : Evidence, proof, and facts: a book of sources, Google Books

- ^ Henk J.M. Bos: Descartes, Elisabeth and Apollonius’ Problem. In The Correspondence of René Descartes 1643, Quæstiones Infinitæ, pages 202–212. Zeno Institute of Philosophy, Utrecht, Theo Verbeek edition, Erik-Jan Bos and Jeroen van de Ven, 2003

- ^ a b c Dhombres, Jean. François Viète et la Réforme. Available at cc-parthenay.fr (French)

- ^ De Thou, Jacques-Auguste available at L'histoire universelle (fr) and at Universal History (en)

- ^ Harvard abstracts about Harmonicum Celestae : Adsabs.harvard.edu

- ^ Letter from Descartes to Mersenne. (PDF) Pagesperso-orange.fr, February 20, 1639 (French)

- ^ Archive.org, Charles Adam, Vie et Oeuvre de Descartes Paris, L Cerf, 1910, p 215.

- ^ Chikara Sasaki. Descartes' mathematical thought p.259

Bibliography

- Bailey Ogilvie, Marilyn; Dorothy Harve, Joy. The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science: L-Z. Google Books. p 985.

- Bashmakova, Izabella Grigorievna; Smirnova Galina S; Shenitzer, Abe. The Beginnings and Evolution of Algebra. Google Books. pp. 75 -.

- Biard, Joel; Rāshid, Rushdī. Descartes and the Middle Ages. Centre national de la recherche scientifique. Google Books (French)

- Burton, David M (1985). The History of Mathematics: An Introduction. Newton, Massachusetts: Allyn and Bacon, Inc.

- Cajori (1919). A history of mathematics. pp. 152 onwards. US.archive.org

- Calinger, Ronald (ed.) (1995). Classics of Mathematics. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Calinger, Ronald. Vita mathematica. Mathematical Association of America. Google Books

- Chabert, Jean-Luc; Barbin, Évelyne; Weeks, Chris. A History of Algorithms. Google Books

- Derby Shire, John (2006). Unknown Quantity a Real and Imaginary History of Algebra. Scribd.com

- Eves, Howard (1980). Great Moments in Mathematics (Before 1650). The Mathematical Association of America. Google Books

- Grisard, J. (1968) François Viète, mathematician of the and XVIth century. Bibliographic essay. (Thèse de doctorat de 3ème cycle) École Pratique des Hautes Études, Centre de Recherche d'Histoire des Sciences et des Techniques, Paris. (French)

- Godard, Gaston. François Viète (1540–1603), Father of Modern Algebra. Université de Paris-VII, France, Recherches vendéennes. ISSN 1257-7979 (French)

- W. Hadd, Richard. On the shoulders of merchants. Google Books

- Hofmann, Joseph E (1957). The History of Mathematics, translated by F. Graynor and H. O. Midonick. New York, New York: The Philosophical Library.

- Joseph, Anthony. Round tables. European Congress of Mathematics. Google Books

- Michael Sean Mahoney (1994). The mathematical career of Pierre de Fermat (1601–1665). Google Books

- Jacob Klein. Die griechische Logistik und die Entstehung der Algebra in: Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der Mathematik, Astronomie und Physik, Abteilung B: Studien, Band 3, Erstes Heft, Berlin 1934, p. 18-105 and Zweites Heft, Berlin 1936, p. 122-235; republished in English as: Greek Mathematical Thought and the Origin of Algebra. Cambridge, Mass. 1968, ISBN 0-486-27289-3

- Nadine Bednarz, Carolyn Kieran, Lesley Lee. Approaches to algebra. Google Books

- Otte, Michael; Panza, Marco. Analysis and Synthesis in Mathematics. Google Books

- M. Pycior, Elena. Symbols, Impossible Numbers, and Geometric Entanglements. Google Books

- Francisci Vietae Opera Mathematica, collected by F. Van Schooten. Leyde, Elzévir, 1646, p. 554 Hildesheim-New-York: Georg Olms Verlag (1970). (Latin)

- The intégral corpus (excluding Harmonicon) was published by Frans van Schooten, professor at Leyde asFrancisci Vietæ. Opera mathematica, in unum volumen congesta ac recognita, opera atque studio Francisci a Schooten, Officine de Bonaventure et Abraham Elzevier, Leyde, 1646. Gallica.bnf.fr (pdf). (Latin)

- Stillwell, John. Mathematics and its history. Google Books

- Varadarajan, V. S. (1998). Algebra in Ancient and Modern Times The American Mathematical Society. Google Books

- Viète, François (1983). The Analytic Art, translated by T. Richard Witmer. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press.

Web pages

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "François Viète", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Viete.html.

- Francois Viète: Father of Modern Algebraic Notation

- The Lawyer and the Gambler

- Robin Hartshorne at Berkeley

- About Tarporley

- Site de Jean-Paul Guichard (French)

- L'algèbre nouvelle (French)

- About the HarmoniconPDF (200 KB). (French)