Velocity

In physics, velocity is speed in a given direction. Speed describes only how fast an object is moving, whereas velocity gives both the speed and direction of the object's motion. To have a constant velocity, an object must have a constant speed and motion in a constant direction. Constant direction typically constrains the object to motion in a straight path. A car moving at a constant 20 kilometers per hour in a circular path does not have a constant velocity. The rate of change in velocity is acceleration. Velocity is a vector physical quantity; both magnitude and direction are required to define it. The scalar absolute value (magnitude) of velocity is speed, a quantity that is measured in metres per second (m/s or ms−1) when using the SI (metric) system.

For example, "5 metres per second" is a scalar and not a vector, whereas "5 metres per second east" is a vector. The average velocity v of an object moving through a displacement  during a time interval

during a time interval  is described by the formula:

is described by the formula:

The rate of change of velocity is acceleration – how an object's speed or direction of travel changes over time, and how it is changing at a particular point in time.

Contents |

Equation of motion

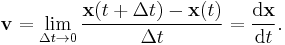

The velocity vector v of an object that has positions x(t) at time t and x at time

at time  , can be computed as the derivative of position:

, can be computed as the derivative of position:

Average velocity magnitudes always smaller than or equal to average speed of a given particle. Instantaneous velocity is always tangential to trajectory. Slope of tangent of position or displacement time graph is instantaneous velocity and its slope of chord is average velocity.

The equation for an object's velocity can be obtained mathematically by evaluating the integral of the equation for its acceleration beginning from some initial period time  to some point in time later

to some point in time later  .

.

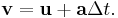

The final velocity v of an object which starts with velocity u and then accelerates at constant acceleration a for a period of time  is:

is:

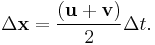

The average velocity of an object undergoing constant acceleration is  , where u is the initial velocity and v is the final velocity. To find the position, x, of such an accelerating object during a time interval,

, where u is the initial velocity and v is the final velocity. To find the position, x, of such an accelerating object during a time interval,  , then:

, then:

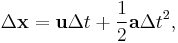

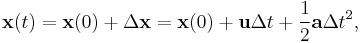

When only the object's initial velocity is known, the expression,

can be used.

This can be expanded to give the position at any time t in the following way:

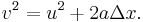

These basic equations for final velocity and position can be combined to form an equation that is independent of time, also known as Torricelli's equation:

The above equations are valid for both Newtonian mechanics and special relativity. Where Newtonian mechanics and special relativity differ is in how different observers would describe the same situation. In particular, in Newtonian mechanics, all observers agree on the value of t and the transformation rules for position create a situation in which all non-accelerating observers would describe the acceleration of an object with the same values. Neither is true for special relativity. In other words only relative velocity can be calculated.

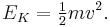

In Newtonian mechanics, the kinetic energy (energy of motion),  , of a moving object is linear with both its mass and the square of its velocity:

, of a moving object is linear with both its mass and the square of its velocity:

The kinetic energy is a scalar quantity.

Escape velocity is the minimum velocity a body must have in order to escape from the gravitational field of the earth. To escape from the Earth's gravitational field an object must have greater kinetic energy than its gravitational potential energy. The value of the escape velocity from the Earth's surface is approximately 11100 m/s.

Relative velocity

Relative velocity is a measurement of velocity between two objects as determined in a single coordinate system. Relative velocity is fundamental in both classical and modern physics, since many systems in physics deal with the relative motion of two or more particles. In Newtonian mechanics, the relative velocity is independent of the chosen inertial reference frame. This is not the case anymore with special relativity in which velocities depend on the choice of reference frame.

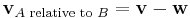

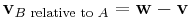

If an object A is moving with velocity vector v and an object B with velocity vector w, then the velocity of object A relative to object B is defined as the difference of the two velocity vectors:

Similarly the relative velocity of object B moving with velocity w, relative to object A moving with velocity v is:

Usually the inertial frame is chosen in which the latter of the two mentioned objects is in rest.

Scalar velocities

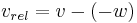

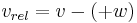

In the one dimensional case,[1] the velocities are scalars and the equation is either:

, if the two objects are moving in opposite directions, or:

, if the two objects are moving in opposite directions, or: , if the two objects are moving in the same direction.

, if the two objects are moving in the same direction.

Polar coordinates

In polar coordinates, a two-dimensional velocity is described by a radial velocity, defined as the component of velocity away from or toward the origin (also known as velocity made good), and an angular velocity, which is the rate of rotation about the origin (with positive quantities representing counter-clockwise rotation and negative quantities representing clockwise rotation, in a right-handed coordinate system).

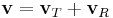

The radial and angular velocities can be derived from the Cartesian velocity and displacement vectors by decomposing the velocity vector into radial and transverse components. The transverse velocity is the component of velocity along a circle centered at the origin.

where

is the transverse velocity

is the transverse velocity is the radial velocity.

is the radial velocity.

The magnitude of the radial velocity is the dot product of the velocity vector and the unit vector in the direction of the displacement.

where

is displacement.

is displacement.

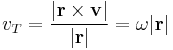

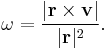

The magnitude of the transverse velocity is that of the cross product of the unit vector in the direction of the displacement and the velocity vector. It is also the product of the angular speed  and the magnitude of the displacement.

and the magnitude of the displacement.

such that

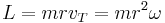

Angular momentum in scalar form is the mass times the distance to the origin times the transverse velocity, or equivalently, the mass times the distance squared times the angular speed. The sign convention for angular momentum is the same as that for angular velocity.

where

is mass

is mass

The expression  is known as moment of inertia. If forces are in the radial direction only with an inverse square dependence, as in the case of a gravitational orbit, angular momentum is constant, and transverse speed is inversely proportional to the distance, angular speed is inversely proportional to the distance squared, and the rate at which area is swept out is constant. These relations are known as Kepler's laws of planetary motion.

is known as moment of inertia. If forces are in the radial direction only with an inverse square dependence, as in the case of a gravitational orbit, angular momentum is constant, and transverse speed is inversely proportional to the distance, angular speed is inversely proportional to the distance squared, and the rate at which area is swept out is constant. These relations are known as Kepler's laws of planetary motion.

See also

- Escape velocity

- Four-velocity (relativistic version of velocity for Minkowski spacetime)

- Group velocity

- Hypervelocity

- Kinematics

- Phase velocity

- Proper velocity (in relativity, using traveler time instead of observer time)

- Rapidity (a version of velocity additive at relativistic speeds)

- Relative velocity

- Terminal velocity

- Velocity vs. time graph

References

- Robert Resnick and Jearl Walker, Fundamentals of Physics, Wiley; 7 Sub edition (June 16, 2004). ISBN 0471232319.

External links

- Physicsclassroom.com, Speed and Velocity

- Introduction to Mechanisms (Carnegie Mellon University)

|

|||||||