Troposphere

The troposphere is the lowest portion of Earth's atmosphere. It contains approximately 80% of the atmosphere's mass and 99% of its water vapor and aerosols.[1] The average depth of the troposphere is approximately 17 km (11 mi) in the middle latitudes. It is deeper in the tropics, up to 20 km (12 mi), and shallower near the polar regions, at 7 km (4.3 mi) in summer, and indistinct in winter. The lowest part of the troposphere, where friction with the Earth's surface influences air flow, is the planetary boundary layer. This layer is typically a few hundred meters to 2 km (1.2 mi) deep depending on the landform and time of day. The border between the troposphere and stratosphere, called the tropopause, is a temperature inversion.[2]

The word troposphere derives from the Greek: tropos for "turning" or "mixing," reflecting the fact that turbulent mixing plays an important role in the troposphere's structure and behavior. Most of the phenomena we associate with day-to-day weather occur in the troposphere.[2]

Contents |

Pressure and temperature structure

Composition

The chemical composition of the troposphere is essentially uniform, with the notable exception of water vapor. The source of water vapor is at the surface through the processes of evaporation and transpiration. Furthermore the temperature of the troposphere decreases with height, and saturation vapor pressure decreases strongly as temperature drops, so the amount of water vapor that can exist in the atmosphere decreases strongly with height. Thus the proportion of water vapor is normally greatest near the surface and decreases with height.

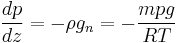

Pressure

The pressure of the atmosphere is maximum at sea level and decreases with higher altitude. This is because the atmosphere is very nearly in hydrostatic equilibrium, so that the pressure is equal to the weight of air above a given point. The change in pressure with height, therefore can be equated to the density with this hydrostatic equation:[3]

where:

-

- gn is the standard gravity

- ρ is the density

- z is the altitude

- p is the pressure

- R is the gas constant

- T is the thermodynamic (absolute) temperature

- m is the molar mass

Since temperature in principle also depends on altitude, one needs a second equation to determine the pressure as a function of height, as discussed in the next section.*

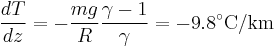

Temperature

The temperature of the troposphere generally decreases as altitude increases. The rate at which the temperature decreases,  , is called the environmental lapse rate (ELR). The ELR is nothing more than the difference in temperature between the surface and the tropopause divided by the height. The reason for this temperature difference is the absorption of the sun's energy occurs at the ground which heats the lower levels of the atmosphere, and the radiation of heat occurs at the top of the atmosphere cooling the earth, this process maintaining the overall heat balance of the earth.

, is called the environmental lapse rate (ELR). The ELR is nothing more than the difference in temperature between the surface and the tropopause divided by the height. The reason for this temperature difference is the absorption of the sun's energy occurs at the ground which heats the lower levels of the atmosphere, and the radiation of heat occurs at the top of the atmosphere cooling the earth, this process maintaining the overall heat balance of the earth.

As parcels of air in the atmosphere rise and fall, they also undergo changes in temperature for reasons described below. The rate of change of the temperature in the parcel may be less than or more than the ELR. When a parcel of air rises, it expands, because the pressure is lower at higher altitudes. As the air parcel expands, it pushes on the air around it, doing work; but generally it does not gain heat in exchange from its environment, because its thermal conductivity is low (such a process is called adiabatic). Since the parcel does work and gains no heat, it loses energy, and so its temperature decreases. (The reverse, of course, will be true for a sinking parcel of air.) [2]

Since the heat exchanged  is related to the entropy change

is related to the entropy change  by

by  , the equation governing the temperature as a function of height for a thoroughly mixed atmosphere is

, the equation governing the temperature as a function of height for a thoroughly mixed atmosphere is

where S is the entropy. The rate at which temperature decreases with height under such conditions is called the adiabatic lapse rate.

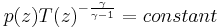

For dry air, which is approximately an ideal gas, we can proceed further. The adiabatic equation for an ideal gas is [4]

where  is the heat capacity ratio (

is the heat capacity ratio ( =7/5, for air). Combining with the equation for the pressure, one arrives at the dry adiabatic lapse rate,[5]

=7/5, for air). Combining with the equation for the pressure, one arrives at the dry adiabatic lapse rate,[5]

If the air contains water vapor, then cooling of the air can cause the water to condense, and the behavior is no longer that of an ideal gas. If the air is at the saturated vapor pressure, then the rate at which temperature drops with height is called the saturated adiabatic lapse rate. More generally, the actual rate at which the temperature drops with altitude is called the environmental lapse rate. In the troposphere, the average environmental lapse rate is a drop of about 6.5 °C for every 1 km (1,000 meters) in increased height.[2]

The environmental lapse rate (the actual rate at which temperature drops with height,  ) is not usually equal to the adiabatic lapse rate (or correspondingly,

) is not usually equal to the adiabatic lapse rate (or correspondingly,  ). If the upper air is warmer than predicted by the adiabatic lapse rate (

). If the upper air is warmer than predicted by the adiabatic lapse rate ( ), then when a parcel of air rises and expands, it will arrive at the new height at a lower temperature than its surroundings. In this case, the air parcel is denser than its surroundings, so it sinks back to its original height, and the air is stable against being lifted. If, on the contrary, the upper air is cooler than predicted by the adiabatic lapse rate, then when the air parcel rises to its new height it will have a higher temperature and a lower density than its surroundings, and will continue to accelerate upward.[2][3]

), then when a parcel of air rises and expands, it will arrive at the new height at a lower temperature than its surroundings. In this case, the air parcel is denser than its surroundings, so it sinks back to its original height, and the air is stable against being lifted. If, on the contrary, the upper air is cooler than predicted by the adiabatic lapse rate, then when the air parcel rises to its new height it will have a higher temperature and a lower density than its surroundings, and will continue to accelerate upward.[2][3]

Temperatures decrease at middle latitudes from an average of 15°C at sea level to about -55°C at the top of the tropopause. At the poles, the troposphere is thinner and the temperature only decreases to -45°C, while at the equator the temperature at the top of the troposphere can reach -75°C.

Tropopause

The tropopause is the boundary region between the troposphere and the stratosphere.

Measuring the temperature change with height through the troposphere and the stratosphere identifies the location of the tropopause. In the troposphere, temperature decreases with altitude. In the stratosphere, however, the temperature remains constant for a while and then increases with altitude. The region of the atmosphere where the lapse rate changes from positive (in the troposphere) to negative (in the stratosphere), is defined as the tropopause.[2] Thus, the tropopause is an inversion layer, and there is little mixing between the two layers of the atmosphere.

Atmospheric flow

The flow of the atmosphere generally moves in a west to east direction. This however can often become interrupted, creating a more north to south or south to north flow. These scenarios are often described in meteorology as zonal or meridional. These terms, however, tend to be used in reference to localised areas of atmosphere (at a synoptic scale)). A fuller explanation of the flow of atmosphere around the Earth as a whole can be found in the three-cell model.

Zonal Flow

A zonal flow regime is the meteorological term meaning that the general flow pattern is west to east along the Earth's latitude lines, with weak shortwaves embedded in the flow.[6] The use of the word "zone" refers to the flow being along the Earth's latitudinal "zones". This pattern can buckle and thus become a meridional flow.

Meridional flow

When the zonal flow buckles, the atmosphere can flow in a more longitudinal (or meridional) direction, and thus the term "meridional flow" arises. Meridional flow patterns feature strong, amplified troughs and ridges, with more north-south flow in the general pattern than west-to-east flow.[7]

Three-cell model

The three cells model attempts to describe the actual flow of the Earth's atmosphere as a whole. It divides the Earth into the tropical (Hadley cell), mid latititude (Ferrel cell), and polar (polar cell) regions, dealing with energy flow and global circulation. Its fundamental principle is that of balance - the energy that the Earth absorbs from the sun each year is equal to that which it loses back into space, but this however is not a balance precisely maintained in each latitude due to the varying strength of the sun in each "cell" resulting from the tilt of the Earth's axis in relation to its orbit. It demonstrates that a pattern emerges to mirror that of the ocean - the tropics do not continue to get warmer because the atmosphere transports warm air poleward and cold air equatorward, the purpose of which appears to be that of heat and moisture distribution around the planet.[8]

Synoptic scale observations and concepts

Forcing

Forcing is a term used by meteorologists to describe the situation where a change or an event in one part of the atmosphere causes a strengthening change in another part of the atmosphere. It is usually used to describe connections between upper, middle or lower levels (such as upper-level divergence causing lower level convergence in cyclone formation), but can sometimes also be used to describe such connections over distance rather than height alone. In some respects, tele-connections could be considered a type of forcing.

Divergence and Convergence

An area of convergence is one in which the total mass of air is increasing with time, resulting in an increase in pressure at locations below the convergence level (recall that atmospheric pressure is just the total weight of air above a given point). Divergence is the opposite of convergence - an area where the total mass of air is decreasing with time, resulting in falling pressure in regions below the area of divergence. Where divergence is occurring in the upper atmosphere, there will be air coming in to try to balance the net loss of mass (this is called the principle of mass conservation), and there is a resulting upward motion (positive vertical velocity). Another way to state this is to say that regions of upper air divergence are conducive to lower level convergence, cyclone formation, and positive vertical velocity. Therefore, identifying regions of upper air divergence is an important step in forecasting the formation of a surface low pressure area.

References

- ^ McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Science & Technology. (1984). Troposhere. "It contains about four-fifths of the mass of the whole atmosphere."

- ^ a b c d e f Danielson, Levin, and Abrams, Meteorology, McGraw Hill, 2003

- ^ a b Landau and Lifshitz, Fluid Mechanics, Pergamon, 1979

- ^ Landau and Lifshitz, Statistical Physics Part 1, Pergamon, 1980

- ^ Kittel and Kroemer, Thermal Physics, Freeman, 1980; chapter 6, problem 11

- ^ "American Meteorological Society Glossary - Zonal Flow". Allen Press Inc.. June 2000. http://amsglossary.allenpress.com/glossary/search?id=zonal-flow1. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ "American Meteorological Society Glossary - Meridional Flow". Allen Press Inc.. June 2000. http://amsglossary.allenpress.com/glossary/search?id=meridional-flow1. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ^ "Meteorology - MSN Encarta, "Energy Flow and Global Circulation"". Encarta.Msn.com. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. http://www.webcitation.org/5kwbSx0AG. Retrieved 2006-10-13.

External links

- Composition of the Atmosphere, from the University of Tennessee Physics dept.

- Chemical Reactions in the Atmosphere

- http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761571037_3/Meteorology.html#s12 (Archived 2009-10-31)

|

|

|||||||||||